Cool Kid Places

Office Party applies architecture to parties and parties to architecture.

Office Party is a 2024 League Prize winner.

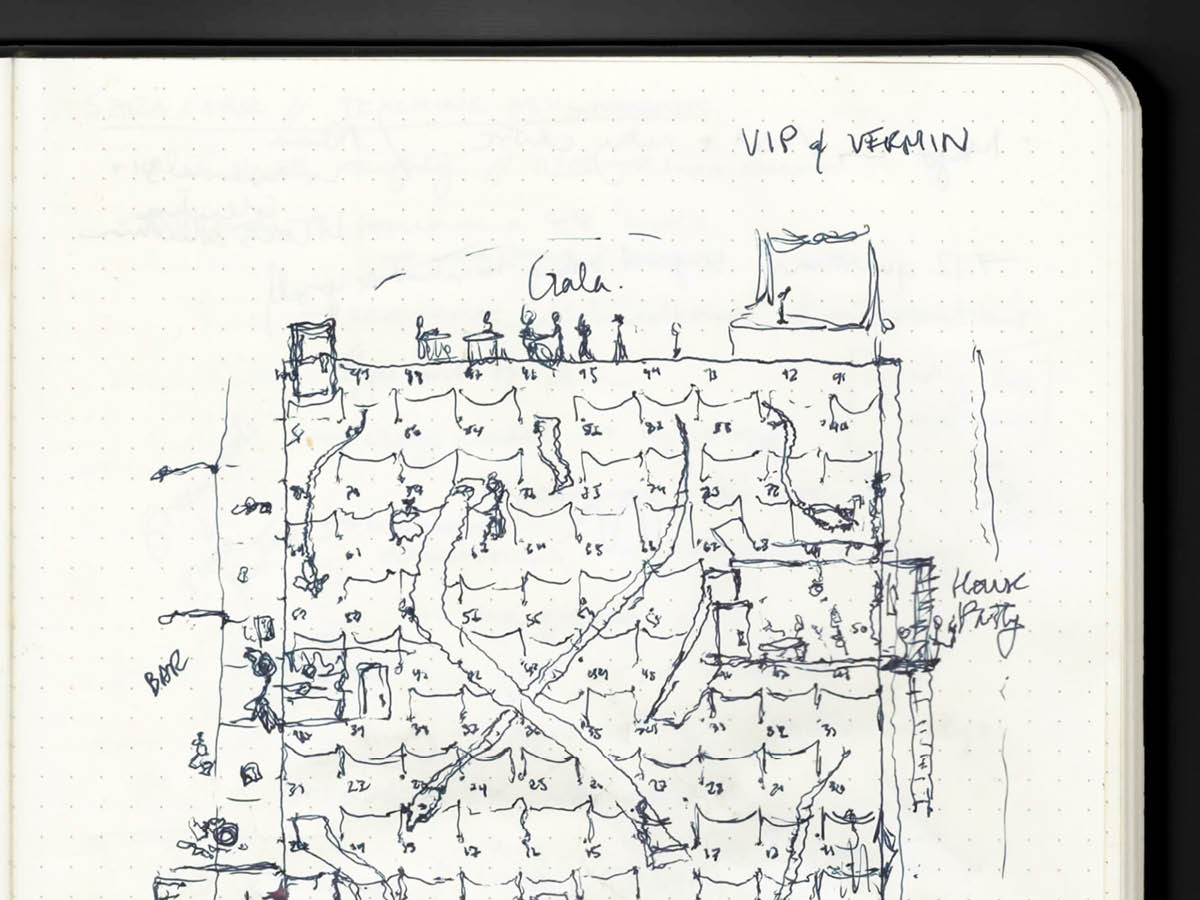

The research and design collective Office Party produces temporary events, installations, and publications that investigate “the role of parties and similar ephemeral spaces as the origin of complex social and material networks with urban, political, and environmental effects,” in the group’s own words. For their League Prize installation, Door Policy, the collective created an interactive game that simulates a night of partying, inviting players to think about the power structures that mediate access to nightlife institutions through the concept of the door.

This summer, the League’s Demasi Darby-Washington spoke with Office Party’s founding members Chase Galis, Christina Moushoul, and Sonia Sobrino Ralston about the project.

*

Demasi Darby-Washington: How did you conceive Door Policy in response to the theme of “Dirty?” Who did you have in mind for the audience and what were some imagined responses?

Chase Galis: The concept of the door in relation to parties has been something that we’ve been thinking about for a while. A lot of our work addresses and tries to embrace the ways that parties produce a dirtiness that escapes supposed architectural expertise. It has to do with the interactions between people, music, networks that are brought into contact, substance consumption—all of these things that interact in a relatively volatile, temporally-specific way.

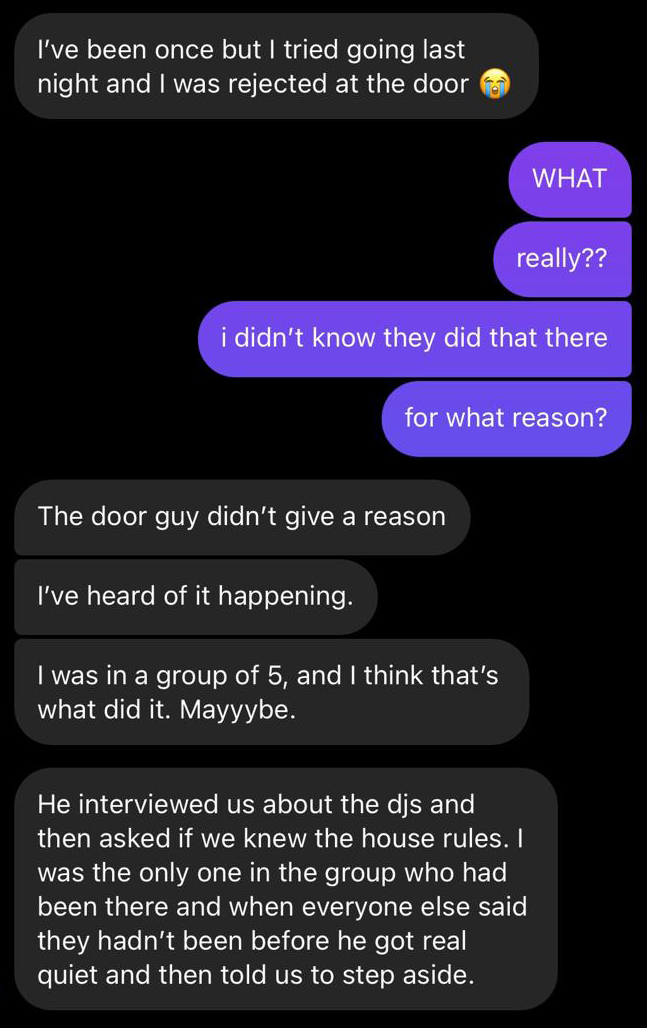

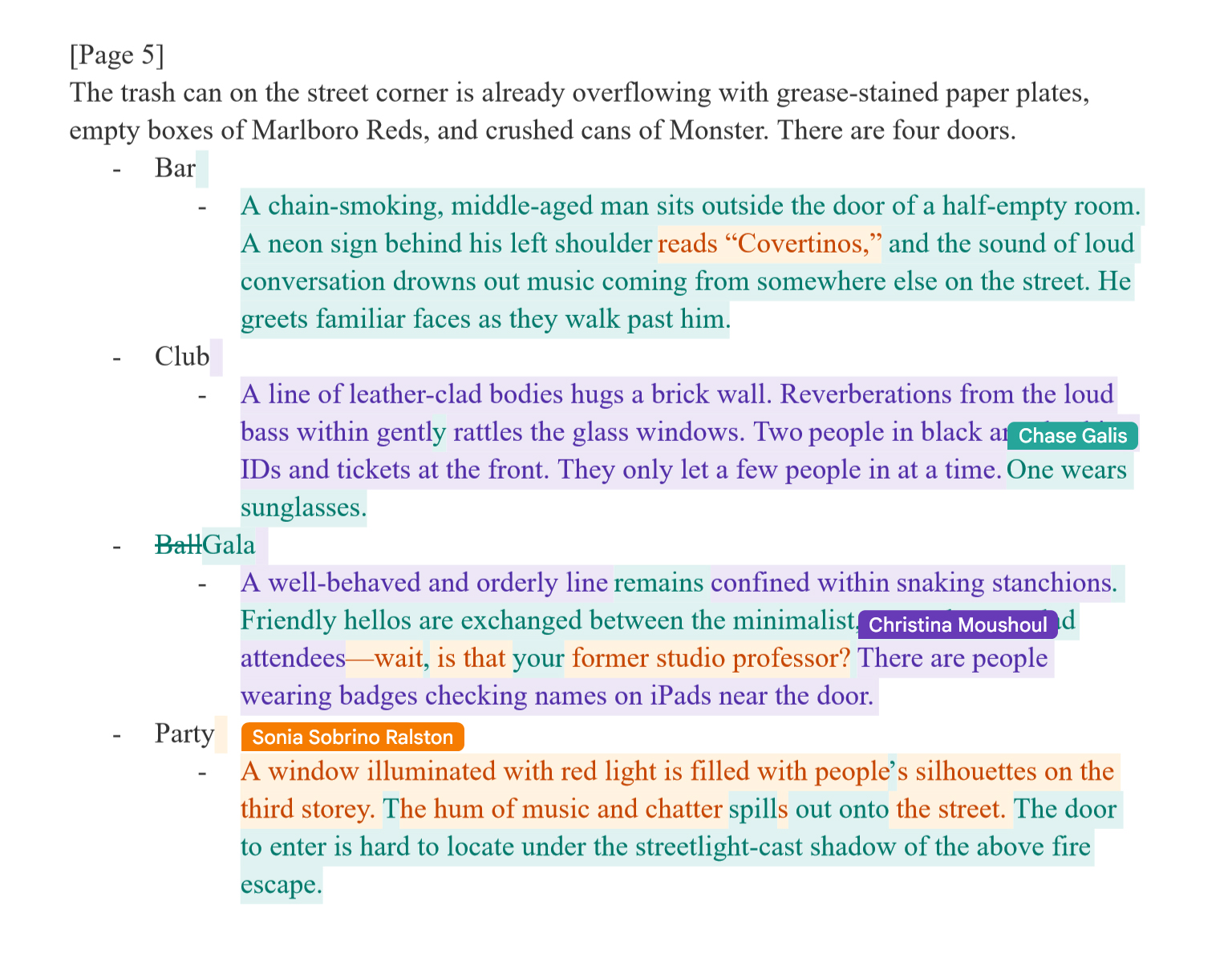

With that said, the door is one of the most significant points of control for mediating or moderating the chaos that can happen during an event, and there are specific ways that those [doors] are handled. Historically, and even today, nightlife spaces, prestigious galas, dinner parties—they all have different techniques, materials, media, and also different social politics that govern who is and who isn’t allowed to enter the party, and that ends up shaping what happens on the other side of the door.

Sonia Sobrino Ralston: When we were thinking about which venues to include in the installation, the audience we were imagining is people who pay attention to The Architectural League, the architecture crowd of New York and beyond. I think for all of us, and probably everyone who has ever been to any of these “cool kid” places in New York, there’s definitely a feeling of not belonging. That was part of the idea of the installation: to focus on these spaces that we’ve all felt some degree of belonging or not belonging to and trying to unpeel that.

Darby-Washington: Apart from Chutes and Ladders, what were your references for creating Door Policy?

Christina Moushoul: We referenced Choose Your Own Adventure games. We felt that both the board game and narrative game encapsulated what it feels to go out for a night in the city, in the sense that somewhat arbitrary or quick decisions can cascade and then lead you down certain rabbit holes. It makes clear the ways that social situations or encounters also shape our individual experiences of the material world. The board game is nice because it also references chance and lack of control.

Galis: We deeply admire the work of Fiona Connor. Connor is a sculptor based in Los Angeles. Her practice relies a lot on documenting architectural elements, abstracting them or extracting them from their original context and recreating them as sculpture in a gallery setting. She had a show a few years ago called Closed Down Clubs [which presented a series of recreated doors based on entrances to closed down nightclubs in Los Angeles]. We were thinking about what happens when you take the door outside of its architectural setting and start to think about the politics of the door itself.

Ralston: There’s a movie, After Hours, in which a series of accidents happen to this guy on his night out. There are dark things happening, but the movie presents this accumulation of decisions—everything comes back and overlaps with each other. We thought that would be an interesting way to conceptualize the project: as happenstance encounters that build into each other.

Darby-Washington: One of Office Party’s aims as a practice is to, as described on your website, “investigate the ways that parties provide insight into the development of architecture as a temporary and responsive mode of space-making.” In what ways can Door Policy teach architectural designers about space-making? How do you imagine the game ultimately impacting the built environment?

Galis: This project has to do with power and where that’s located, but it recognizes that the door alone isn’t enough to exert control, so often a party will turn to other techniques of enforcement: written policy, cameras, a bouncer, velvet rope, the posted hours of operation for a bar, a dress code.

Moushoul: Questions of soft and hard power, as well as control and agency of the architect, arise. How far can an architect extend their reach? You may design a space that in its physical form, you imagine, connotes forms of accessibility, but the use of that space—and the policies or structures that are beyond the role of the architect—might change who can enter space, what they can do, and if they feel comfortable.

Ralston: Earlier this year, Christina and I hosted a discussion about Office Party’s publication, Party Planner. We invited different people to think about party planning together: architect Safwat Riad, club DJ and organizer Alyce Currier, and Ivan L. Munuera, an architectural historian. And what was interesting to have all these different people talking about, which I think is reflected in the League Prize installation, was that the design of the space can only do so much to shape behavior or atmosphere. But if you have more people at the table to talk not just about physical architecture but also the social architecture of a space, that allows for different architectural possibilities. And of course, we talked a lot about code and how it facilitates or doesn’t facilitate certain kinds of experiences or access in club spaces.

Darby-Washington: What elements were left out of this iteration of Door Policy? How would you push this installation to be “dirtier?”

Galis: In the writing of the narratives [for the game], we were experimenting with style and a certain level of humor or irony. Some prompts ended up being much more pointed than others, and some were much more specific to social experiences or certain anxieties that we have had ourselves. Exposing those things is a contribution to the dirt of it all, so to speak. Speaking of anxieties, there was an—unavoidable?—element of self-censorship as well, knowing the institutional platform it would be displayed on and how it would be perceived.

Ralston: We spent a long time thinking about [the question that asks] what clothes you would pick to wear. A lot of different language came up when we were writing, like: “You’re putting on your cuntiest fit to go out.” We thought maybe that wouldn’t land with a lot of people. That’s maybe a more banal example of our own self-censorship, but there were others that I won’t mention here.

Darby-Washington: What did having the chance to produce this installation offer to your practice as a whole? What’s next?

Galis: Office Party has been a vehicle for us to push ideas in a way that’s very different from our individual practices. As an entity on its own, it allows us to experiment. Office Party’s institutional relationships are temporary. We’re not living off of them, so we have been able to push things a bit further in certain regards. Addressing these tensions is something that we’re used to and has been productive for our practice overall, negotiating the dirty, sleazy traces of a party against the structure of an institutional setting.

Ralston: The online format was an interesting challenge, to think about how to make an installation that people feel immersed in. Making something that gave the illusion of choice was also an interesting direction to think through. As three people trained in the spatial disciplines, we immediately defaulted to thinking about creating a spatial installation. But with the constraints of making this experience accessible online with a limited digital footprint, exploring strategies like text-based adventure games and the static game board was a new opportunity to imply immersion on a screen, rather than literal immersion in space.

Moushoul: We oscillate between applying architecture to parties and parties to architecture. Working with The Architectural League of New York, it was interesting to introduce our modes of working to this representative of institutional architecture, to try to destabilize it, to dirty it up.

This interview edited and condensed.