Miles Gertler of Common Accounts: You Are Well Liked in Your Community

One of six installations for the digital exhibition by winners of the 2023 League Prize.

“I’ve only got 4,000 followers on twitter. But I’ll share this as much as I can. Truly sorry for your loss.”

Reclaimer, 2014. 3 Likes.

In his 1993 book, The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier, Howard Rheingold, a critic of technology and society, wrote that “you aren’t a real community until you have a funeral.” Thirty years later, ad hoc internet communities regularly spring up around deaths and mourning. The vast volumes of online data left behind when social media users pass away are commonly referred to as digital remains. These traces have been theorized to comprise a kind of virtual afterlife, and novel technologies in deathcare serving both digital and material remains continue to open new frontiers in how memorial might take shape today.

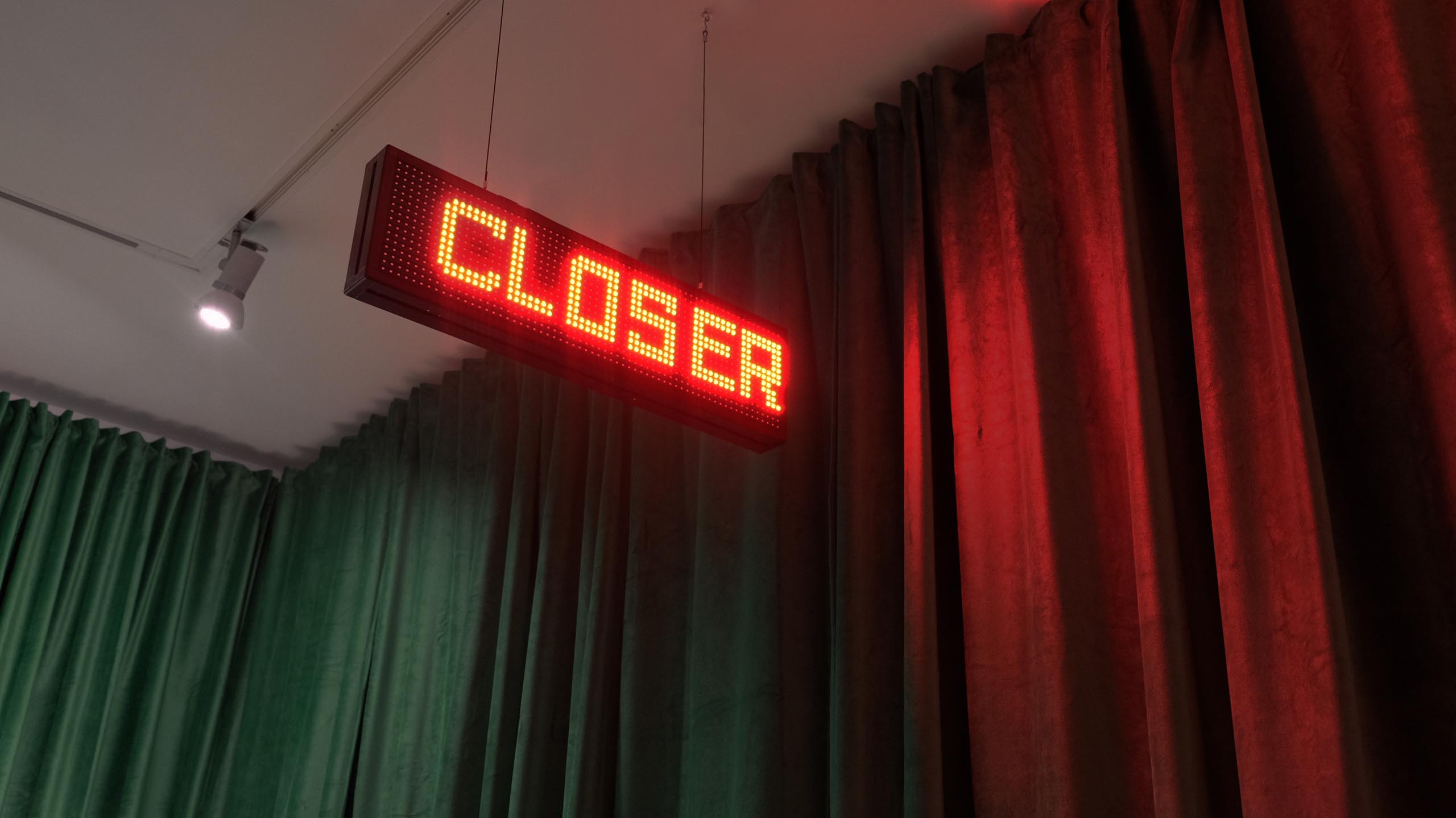

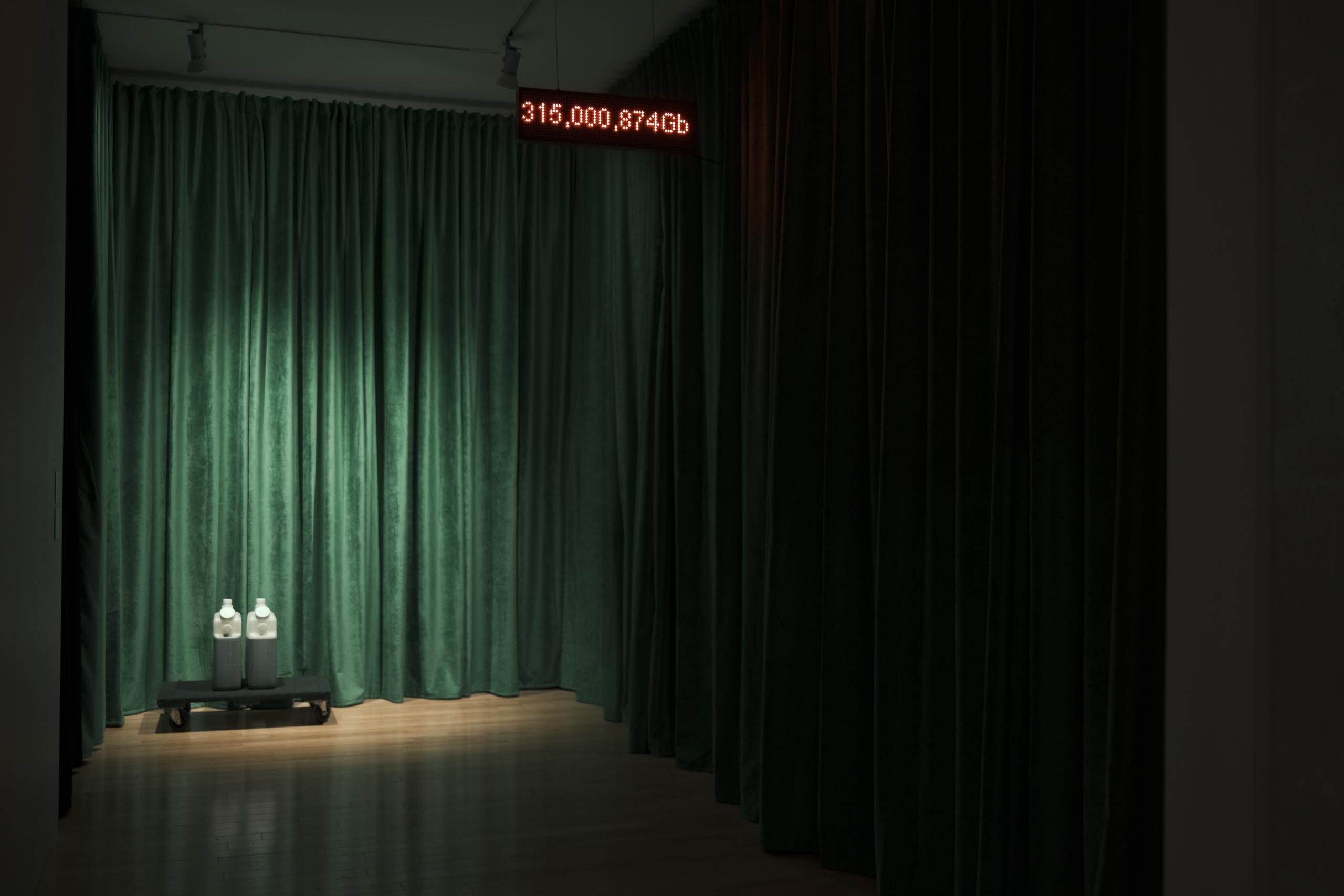

In You Are Well Liked in Your Community, Common Accounts explores the macroscopic and ritual aspects of online death as they imagine bridges between the physical and the virtual: An LED sign exhibiting death-care industry slogans, messages left by mourners in YouTube comments, and measures of datasets of internet users uploaded to Facebook’s Hive storage—virtual bodies sublimated to the cloud. In contrast, a vessel containing fluid from alkaline hydrolysis is present: the effluence of a new ecological disposition method that proposes to mitigate many of the limitations and disadvantages of burial and cremation. As social media platforms become digital cemeteries, You Are Well Liked in Your Community muses on the aesthetics of contemporary death and mourning practices and wonders if we might build value from death’s atomization into daily life.

The approach to You Are Well Liked in Your Community is framed by the gothic arch of the Art Museum of the University of Toronto’s Justina M. Barnicke Gallery. Photo courtesy of Jackson Klie.

You Are Well Liked in Your Community explores ceremonial and aesthetic logics of death today. Photo courtesy of Jackson Klie.

An LED sign hangs above and oscillates between three kinds of message: 1) A simulated live animation of the growing data volume corresponding to Facebook’s accumulated, peta-byte scale data storage across its many storage centers; 2) A mourner’s comment left on John Berlin’s viral “My appeal to Facebook” YouTube video; 3) Tech and death-care industry slogans like LEAVE EVERYTHING TO US, CLOSER EACH DAY, and JOIN LIFE IN THE CLOUD.

“Hello John. I ran across your posting and saw your plea. My son, my only child, Michael also passed away on Feb. 25, 2013. I will never know all the details. I have tried to take over his account but still have not been able to with no response. But, that is okay as long as his videos remain on there forever…”

Melinda Hogue, 2014. 0 Likes.

A central event in Common Accounts’ research into self-design and funereal cultures is the February 2014 viral video, “My appeal to Facebook,” posted by Arnold, Missouri, resident John Berlin, whose son Jesse had died unexpectedly in his sleep in 2012 at the age of 21. Soon after Jesse’s death, John, a middle-aged, out-of-shape, married father of three who lived in a mobile home, started a YouTube channel and discovered the Insanity physical fitness program, by the Santa Monica–based company BeachBody. Berlin turned to exercise to reverse the effects that a sedentary lifestyle had had on his forty-four-year-old body. In 2013 he announced that he was taking on clients as a trainer from his living room, which was now outfitted with a memorial to his dead son, Jesse, on the space’s back wall. Two years after his son’s death, John posted his first viral content, in which he made a plea to Facebook for a “Look Back” video of his dead son’s account.

The Look Back video format is a slideshow of greatest hits from a user’s virtual material, and was a product of Facebook’s tenth anniversary celebrations. Soon after its launch, an emotional Berlin asks Facebook, via YouTube, to generate such a video from the material that he didn’t have access to on his son’s account. After logging two million views in just 48 hours, Berlin received a call from Mark Zuckerberg granting his request and announcing an immediate review into Facebook’s policies toward memorialization and the accounts of dead users.

In the background of the plea video, Berlin’s living room had been further transformed. His son’s memorial wall had been replaced by floor-to-ceiling mirrors, revealing some fitness equipment at the room’s peripheries and the space’s transformation into a home gym. Remote audiences made up of Insanity buffs, fitness trainees, and other spectators had become participants in Berlin’s mourning. His Facebook profile and his comment feeds came to operate as a platform for others to mourn the deaths of those close to them.

With alkaline hydrolysis, human remains are liquified into a fertile solution with many possible applications and possible symbolic forms. You Are Well Liked in Your Community presents actual organic liquid remains on loan from an Ontario funeral home and stored in twin 2.5 gallon HDPE vessels. Photo courtesy of Jackson Klie.

“My son crossed in 2006. He was 23. I understand. I cannot access his MySpace account anymore, they took it down. I totally understand why you did what you had to do. Bless you, from a mom whose child has also gone to the light. hugs.”

mrsbrown333, 2014. 5 Likes.

The living room became a gym in service of memorial and dying. Berlin’s embrace of fitness demonstrates the common ground occupied by the construction and deconstruction of the body. This spills over into design thinking too. The symmetry between technologies for self-construction, maintenance, and healing and those serving death can be observed in 19th-century German architect and historian Gottfried Semper’s description of the Egyptian labra in Style and the Technical and Tectonic Arts: He points, for instance, to the shared typological origin of the bathtub and the sarcophagus. In You Are Well Liked in Your Community, vessels again frame the ceremonial form of the body, contained in this instance as liquid in twin HDPE containers.

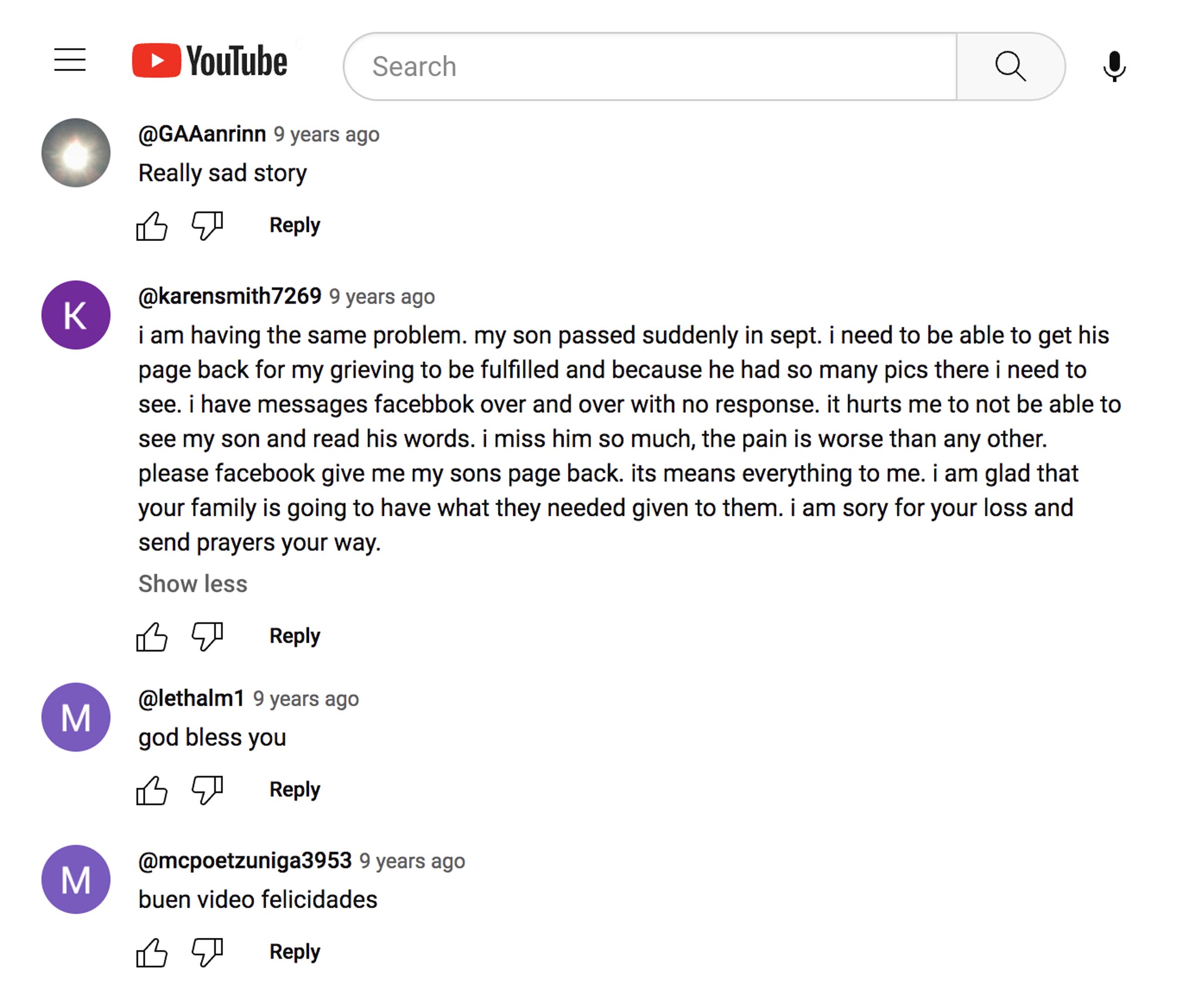

The users’ messages projected on this exhibition’s LED sign were sourced from comments left on Berlin’s viral YouTube video by an ad hoc community of mourners and sympathizers. Many were written by strangers who had encountered losses of their own and identified with John’s desire to access, spend time with, and preserve the digital remains of those close to him.

With alkaline hydrolysis, human remains are liquified into a fertile solution with many possible applications and possible symbolic forms. You Are Well Liked in Your Community presents actual organic liquid remains on loan from an Ontario funeral home and stored in twin 2.5 gallon HDPE vessels.

Comments left on John Berlin’s viral 2014 YouTube video, “My appeal to Facebook,” in which he makes an emotional request for access to content stored on his dead son Jesse’s social media account.

Common Accounts’ work on death understands that funereal ceremony and ritual have often been products of technological circumstance. To that end, the office's work develops the form of funeral today with a distinct interest in managing and celebrating the technological, material business of death.

Project credits

This work was first shown at the Art Museum of the University of Toronto as part of the exhibition Tumbling in Harness, on view in the Justina M. Barnicke Gallery May 3–July 22, 2023.

Project team Miles Gertler and Igor Bragado

Curated by Erin Reznick

Exhibition and Project Coordinator Micah Donovan

Lead Preparator Daniel Griffin Hunt