To achieve climate justice, don’t leave architecture to architects

Environmental justice pioneer Dr. Robert Bullard believes we need new coalitions to plan and design American cities.

Within the past few years, a number of architecture firms and allied organizations have formally declared a climate emergency and pledged to take action. But what should this action involve, and how likely is it to happen at the scale and speed required to prevent the worst outcomes of global warming? In this interview series, the League presents different perspectives on where architecture currently stands with regard to climate action, where it needs to go, and how it might get there.

Dr. Robert Bullard is considered a pioneer of the environmental justice movement, having fought for universal access to healthy, sustainable communities since the 1970s. Trained as a sociologist, he now serves as Distinguished Professor of Urban Planning and Environmental Policy at Texas Southern University in Houston.

The League’s Sarah Wesseler spoke with him about the relationship between design, the built environment, and climate justice.

*

From your perspective, how would you characterize the response to climate change that you’ve seen from the design profession—architects, urban planners, engineers, landscape architects?

Well, I’m a sociologist. Sociology connects people, place, organizations, institutions. The work that I’ve tried to do over the last four decades brings together individuals who are trained in certain disciplines, but who oftentimes don’t cross over into the social and equity aspects of that work. This is true for many people who are working in the built environment. In many cases, the most vulnerable populations are not factored into the design, policy, or financing of specific projects.

In the environmental justice movement, we believe that society should not leave planning just to planners. We should not leave design just to those individuals who are trained as architects or engineers or policy people, because these people may be biased in favor of individuals who are from majority groups, demographically speaking, and who are better off financially. If we talk about designing communities for climate resilience and sustainability and health and livability, equity usually gets left out of the equation—it’s only recently being considered by these professions. That kind of disparity gave rise to the environmental justice movement, and it’s giving rise to a new movement called climate justice.

Look at the way that cities and metropolitan regions are planned and designed. The practices and policies that we typically see actually mitigate against giving everyone access to living conditions that are fair, affordable, accessible, and clean. There are policies that allow communities to become environmental sacrifice zones. That’s how amenities and resources that get allocated in some communities are lacking in other communities, whether that’s parks and green space or grocery stores and adequate transport. That’s why certain areas are saturated with polluting facilities.

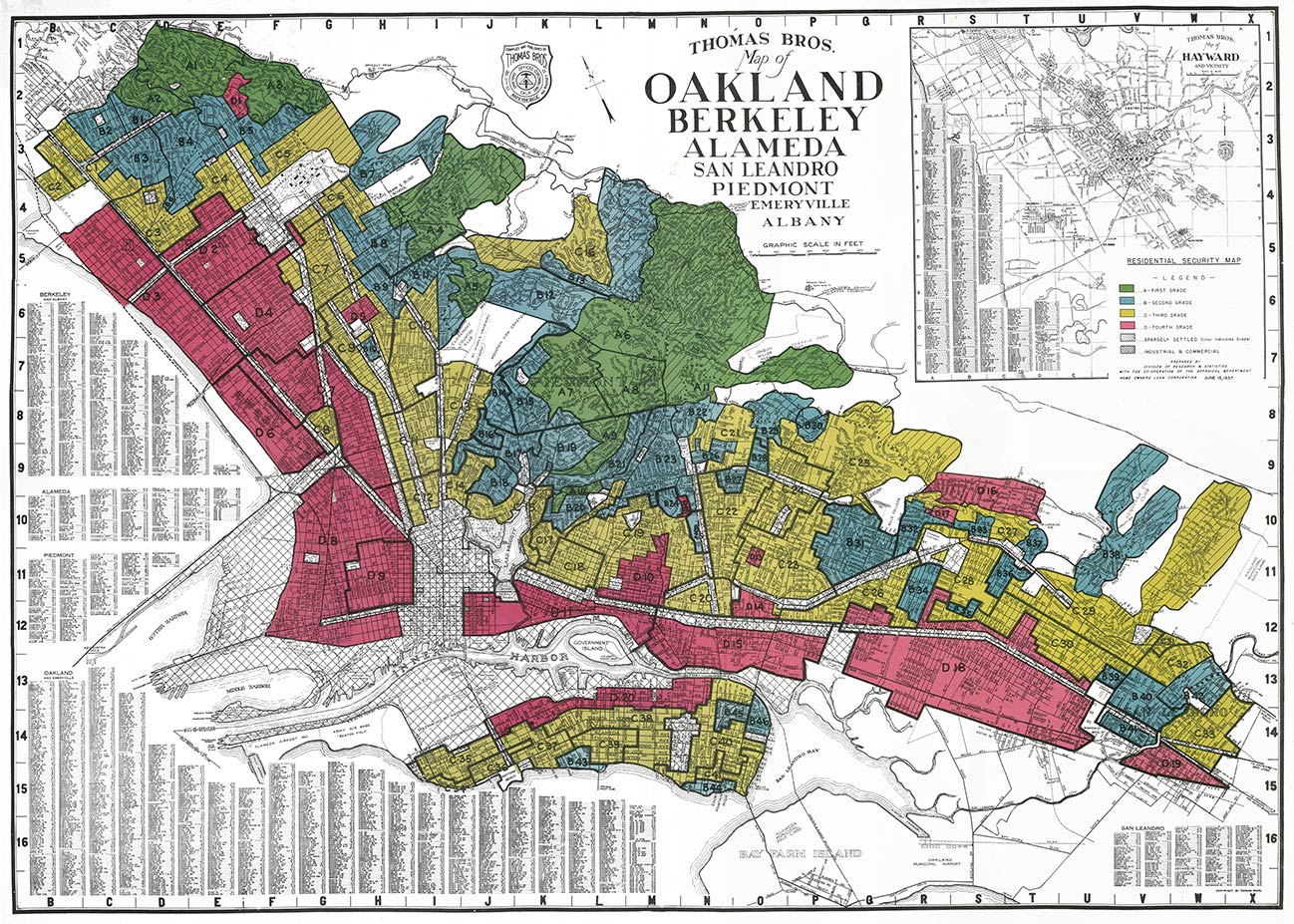

Architecture, planning, health, transportation, land use, food security, finance, climate resilience—all these things are connected. It’s ironic that people who are the most likely to not have cars and are transit dependent are more likely to live in areas that have the most air pollution. Recent studies show that whites are less likely to experience negative impacts from the air pollution they create, whereas people of color are more likely to suffer from the pollution that whites create. Another study shows that the original redlining of the ’30s is showing up today in terms of which neighborhoods have the highest concentration of urban heat islands.

Years and years ago, people would tell you that the ghetto is hot—well, the studies are showing it’s hot. If you don’t have trees and green space, you’ve got a differential of maybe two to fifteen degrees between affluent areas with trees and other areas that are barren.

So if you have architects and planners making plans without taking the political and economic dynamics of the larger system into consideration, these plans will likely exacerbate the inequality. And climate change will exacerbate those existing disparities even more.

Today, there are a lot of projects dealing with issues around sustainability, climate resilience, walkability, and equity. But if the planners, the architects, don’t build equity and health into the framing for these projects, you will get more gentrification, more exclusivity. You’ll get more places that are somehow islands—that don’t provide any heterogeneity in terms of ethnicity, in terms of income, in terms of kinds of occupations of the people who live there.

And you can see that happening right now. If you rank the most walkable neighborhoods, the most sustainable communities, and the areas that are more climate resilient, they’re skewed toward more affluent demographics, and they tend to be whiter than the general population.

And at the same time, the country is becoming more diverse. If you think about climate science, a lot of the scenarios talk about 2040, 2050. Well, in 2040, 2050, the US population will look nothing like our population now. The country is projected to become majority people of color in 2045. But when the professions are planning communities that will still be here in 2050, it’s not uncommon for everyone in the room to be white. It’s not uncommon for them to have no idea what’s happening in communities of color, which are already the frontline communities for climate change. It’s a problem. A lot of issues around lack of empathy or understanding have to do with the lack of diversity in these professions.

Have you worked with architects on these issues? What’s your impression of the discipline’s response to these kinds of critiques?

Well, most architects say, “Oh, no, that’s not what we do. That’s a social issue. We’re builders.” The level of consciousness within these professions is rather low.

I spoke to some minority architects a couple of years ago at their conference, and a lot of them are attuned to these issues. But if they’re in a large firm, and not in their own firm, it’s a fight for them to actually do anything about it. They may be working on a project that the firm won in a bid—well, the bid itself probably doesn’t have anything that comes close to the equity lens that I’m talking about.

In order to get change, the organizations that create the bids, whether they’re public or private, need to explicitly address equity in their procurement process. The businesses submitting bids would then have to respond directly to these equity criteria and explain how they would meet them. The winning bid would then theoretically address some of these issues.

A lot of this comes back to policy. The climate justice lens could be mandatory, like affirmative action used to be. Under the Obama administration, the government was putting in place standards for federal projects that took climate change into consideration. Well, the Trump administration has stripped all that out—it’s like, “Well, we’ve got to take this out, because there’s no such thing as climate change.” But ideally, the projects that the government is accountable for would have to look at climate impacts as well as equity impacts.

My guess is that a lot of architects aren’t sure where to start when it comes to climate justice, assuming they were trained in a traditional way and have spent their careers in traditional practice. What recommendations could you give people who want to get started working on these issues in a meaningful way?

Well, with the technology and tools that we have today, with GIS, we can map the vulnerabilities. We can map the policies that have contributed to the challenges that many communities face, whether it’s housing, transportation, green space, parks, food security, flooding. So it’s not like architects and other design folks are flying blind. When you have that data, and when you see the visual representation of how things have changed over a period of time, you can also project how certain kinds of design, certain kinds of policies, will play out in terms of climate resilience, quality of life, poverty alleviation, health impacts.

But addressing these issues isn’t just a question of design. You need planners and architects, but you also need health professionals, geographers, psychologists. In many communities that have been bombarded with all these environmental stressors, chronic as well as acute, people are experiencing PTSD and ecological stress disorder, anxiety. So you need to bring medical professionals into this mix to deal with not just the health impacts of pollution, urban heat island, heat stress, but also mental stress in the era of climate change. It’s a team approach.

But it’s going to take some work to get there, because some professions are very conservative, and can only see that profession operating in the same way it has since it was founded decades ago, or, in some cases, centuries ago. They’re living on tradition, and oftentimes tradition has gotten in the way in terms of peeling away racism and classism.

There has to be a concerted effort to reach out to organizations, institutions, and networks that are working on these issues and partner with them in a way that’s mutually beneficial. That might sound like a commonplace proposal, but it’s very difficult.

Can you give me an example where you’ve seen that happening, or how you could envision it happening?

I’ll give an example in Houston, post-Harvey. Harvey flooded a lot of neighborhoods that had not flooded before. That forced a lot of on-the-ground environmental organizations that are mostly white—groups that deal with marshland, wetlands, prairie issues, air quality, waste—to rethink how they work.

The storm was an equalizer. Before Harvey, you had these very affluent neighborhoods on the west side—well-heeled, white, well-planned, with lots of amenities, no flooding—and then you had poor communities on the east side that were flooding year after year. Historically, when the groups on the west side thought about environmental justice, it was kind of like, “Oh, that’s a poor people minority thing; that ain’t got nothing to do with us.” But even the smartest people didn’t expect this flood of biblical proportion. Experts were shocked and unprepared.

So a group of us decided that it’s time for folks who hadn’t really worked together to join forces. The environmental justice groups, civil rights groups, neighborhood civic associations that have been fighting for issues like affordable housing on the east side teamed up with the environmental groups on the west side. We organized ourselves into the Coalition for Environment, Equity, and Resilience. It’s about three dozen organizations that work on, well, you name it: affordable housing, flooding, pollution, environmental racism, energy, transportation, parks and green space, food deserts, wetlands.

The thing that connects us is the fact that we are all vulnerable. Harvey showed us that when we do not protect the most vulnerable population in our city, in our county, we place everybody at risk.

One of the first things we did in this coalition was develop an equity lens framework and try to get this language officially adopted by Harris County. We started working on this right after Harvey, but what really made it possible was the 2018 midterm election. That was really a blue wave, and it put Democrats in decision-making positions in the county. So when our equity framework was presented to the Harris County Commission, they adopted it.

Now, this is an experiment, and we don’t know how it’s going to turn out. But we do know that having political will to accept equity into the formula makes a difference, so that the old paradigm—money follows money, money follows power, money follows white—can be changed. The new paradigm is that money should follow need.

I’m very excited. But we could not have gotten this far before Harvey, and it should not take a biblical flood for people to come to these realizations. It’s just common sense. But as my grandma would tell me, common sense is not always so common.

Interview edited and condensed.

Explore

A conversation on race and climate change

A panel discusses race, sustainability, and the intersection of the two.

The future of Zone A: New York neighborhoods on the frontline of climate change

A panel discussion about neighborhoods contending with the effects of climate change.

Adrian Lahoud on the geopolitics of climate change

Adrian Lahoud, Dean of the School of Architecture at the Royal College of Art, discusses how climate action in one place triggers effects elsewhere.