Each of this report’s editors works in affordable housing, and each has a connection to cdcb. Cdcb, or come dream. come build., was founded in 1974 to provide safe, affordable housing options to low-income residents of the Rio Grande Valley. It is a community development corporation unlike any other in Texas, in part because of the range of services it provides in-house. In addition to developing affordable housing, cdcb offers free small dollar loans, financial coaching, pre-purchase and foreclosure prevention housing counseling, VITA [Volunteer Income Tax Assistance] tax preparation, and targeted savings opportunities to assist individuals in accessing tangible products and services that allow them to gain a strong household financial position and accumulate financial reserves. At cdcb many of an individual’s homeownership needs can be met under one roof by people who have knowledge and experience working in the region—a rare and valuable service in the world of affordable housing. And it’s also why cbcb appears many times in this report.

Here, we’ve asked Zoraima Díaz-Pineda of cdcb’s Financial Security program to reflect on the financial wellbeing of Brownsville residents. As others have elucidated, it’s not enough to know or point out that people are struggling or are unwell; we have to understand the root causes. —Lizzie MacWillie, Kelsey Menzel, Jesse Miller, and Josué Ramirez, Brownsville Undercurrents editors

Through an intense review of local household balance sheets, baseline financial health metrics, and behaviors, cdcb has uncovered contours in our regional households’ financial landscape that are not always evident from a cursory review of a subset of national data. As we dive deep into the financial profiles of low-wage earners in our city, we use an intentional health, wealth, and equity perspective to interpret the implications of deep-rooted financial instability. This approach shows us that participants have not had time to develop a sense of household financial competency and confidence because they can’t escape the chronic cycle of financial instability long enough to reach financial health and begin to build wealth. In an effort to help families understand often-confounding financial data points and to create a narrative that resonates with a broader audience of policy advocates, we communicate financial health metrics using physical health terms that everyone is familiar with, which we will also use here—terms like blood pressure, cholesterol, and immune system.

In Brownsville, families are often trapped in a cycle of chronic financial illness on account of eight primary factors, each of which needs strong comprehensive policy solutions to treat the root cause of chronic financial instability.

Problem 1: A rampant case of insufficient income.

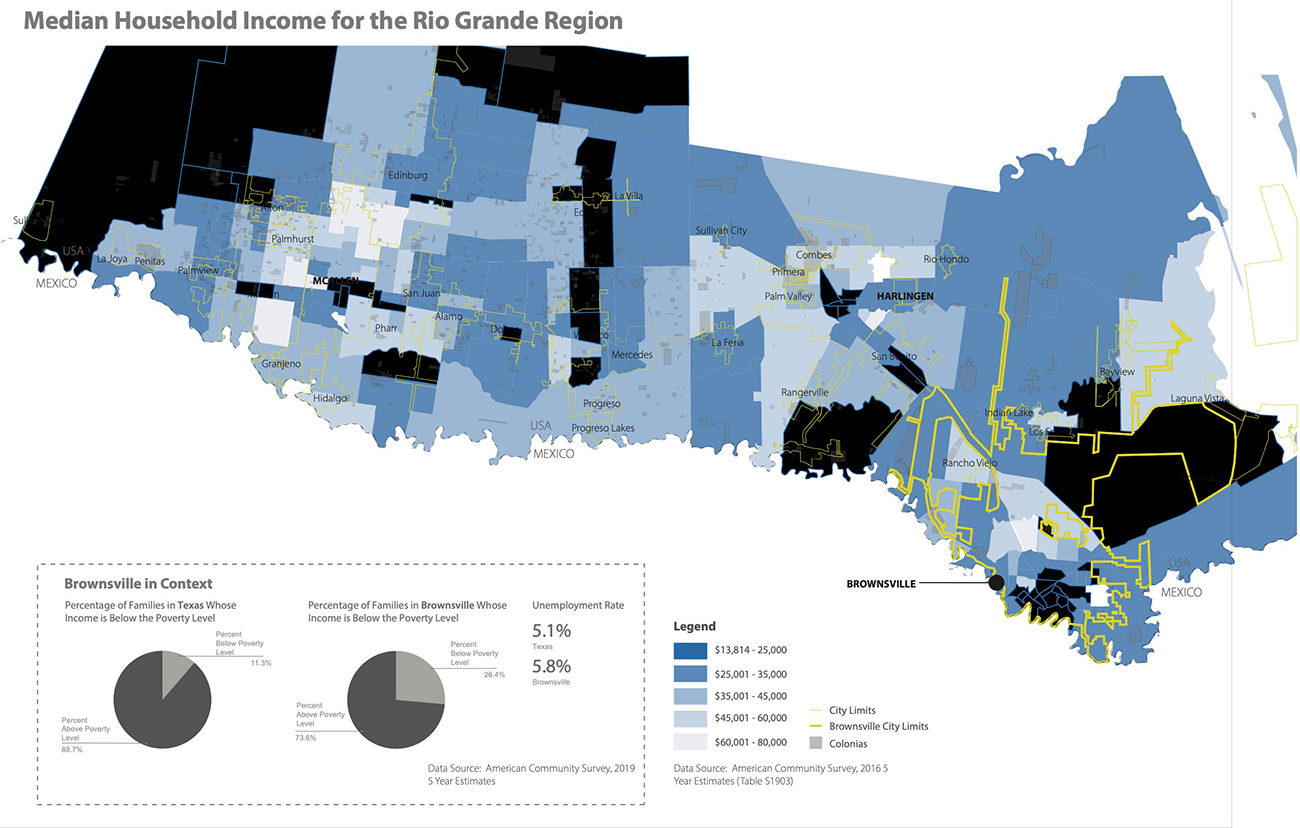

Many individuals earn low wages or survive on a fixed income, thus their financial pulse is not strong enough to flow through their household budget and cover their basic expenses. It is incorrect to assume that the lower cost of living in the southwest border region should allow low-wage earners to stretch their income and cover more expenses. Our clients need to earn at least $13.40 an hour to cover the cost of a 2-bedroom apartment at $697 per month, but since renters in our area only earn $8.78 on average—and more than half of all cdcb clients earn less than $12 per hour—many rely on small-dollar loans as a consistent source of income patching to cover basic living expenses.

During the last year, 19 percent of cdcb’s clients’ sole source of income was either Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), as they are either elderly, disabled, or responsible for the full-time care of a disabled family member. These clients received $883 per month, on average.

Nearly one out of four individuals who file their taxes as head of household receive more than 25 percent of their adjusted gross income in the form of a one-time yearly federal income tax refund. To make ends meet, people take out high-interest predatory loans to cover expenses. We started the Community Loan Center (CLC) to provide an alternative to these predatory loans. The CLC offers low-interest loans with a maximum of $1,000. We partner with employers to offer the loans to employees tying the payback period into their existing income checks, which helps to ensure that the load falls within their budget and provides an equitable payback structure.

In addition to access to the CLC small-dollar loan, cdcb also provides one-to-one, bilingual, culturally relevant financial coaching, with an emphasis on emergency budgeting, debt reduction, and savings.

And yet: Financial coaching and access to sound financial products such as the CLC alternative small-dollar loan are insufficient to mitigate the impact of interruptions clients experience in their income streams.

Policy recommendation: Federal policy measures, such as increasing the minimum wage or a universal basic income, would help treat the root cause of insufficient income and have a far wider impact alongside individual financial coaching and alternative small-dollar loans.

Problem 2: Incongruent income streams and high rates of income volatility.

Many people here fluctuate from one low-wage job to the next, working irregular hours that result in uneven cash flows. This lack of steady income increases the demand for high-cost short-term credit products. For decades, migrant workers in and around Brownsville were employed in seasonal farm labor and experienced predictable cash flows reflecting harvesting schedules. But as the share of migrant farm labor decreases, a large portion of the working-age population experiences lateral employment transfers in the low-wage labor market, with the absence of critical employer benefits. The widespread inability to predict income earned from work makes it nearly impossible for individuals to create a monthly budget. The constant spikes and dips are difficult to manage, leaving low-wage earners with little, if any, disposable income to plan for unexpected expenses.

Policy recommendation: Create policies for portable benefits to provide individuals who fluctuate frequently between low-wage employers with access to short- and long-term financial security.

Problem 3: Unable to save money, families have a critically weak financial immune system.

Fifty-nine percent of all households in Brownsville lack access to cash reserves when they experience a financial emergency. The financial immune system of cdcb’s clients, specifically, is hanging on for dear life: 98 percent of all the families we serve lack access to savings to cover three months of expenses when they encounter a natural disaster, an unanticipated layoff, the onset of a debilitating chronic illness, a sudden family separation, or transportation issues that make it difficult to commute to work.

Moreover, the unprecedented impacts of COVID-19 continue to weaken financial immune systems. Twenty-one percent of individuals in households served by cdcb experienced either a job loss or a reduction in hours in April 2020.

The direct policy solution that was intended to help affected families—the economic impact payment—did provide temporary access to cash. However, the policy was not structured to reach the most vulnerable in our community: households with mixed immigration status, those who lack legal documentation, and elderly primary caregivers with dependents under the age of 18 who fall below the federal income tax filing threshold.

Policy recommendation: Ensure all benefits are available to the most vulnerable.

Problem 4: Many have poor credit, or do not have a formal credit history at all.

Credit is increasingly critical to achieving financial health and building wealth, and our financial coaches constantly monitor their clients’ financial blood sugar level, or credit score, as it dictates the financial products they are eligible for and the type of debt they consume. Presently, financial blood sugar levels reveal that the majority of individuals in our city are credit challenged. Seventy percent of cdcb’s clients during the last fiscal year maintained a subprime credit score, with the average hovering around 480, and 12 percent were credit-invisible, having no credit history. The lack of access to a formal credit history forces individuals to live in the shadows of the credit market. Women, permanent residents, and undocumented individuals are disproportionately impacted. In Cameron County as a whole, only 25 percent of individuals maintain credit utilization rates (the ratio of credit usage to available credit) under 30 percent, and 38 percent of individuals are credit stressed.

Policy recommendation: Modify the current industry standard underwriting criteria to accurately assess the credit strength of low- and moderate-income borrowers by expanding the type of criteria considered. This can help low-income households access wealth-producing assets, such as a home.

Problem 5: We live in a financial services desert.

In Brownsville, the ratio of mainstream financial service providers to predatory financial providers is 1 to 22. Our clients largely operate outside the financial mainstream, in a market saturated by predatory, aggressively marketed, high-cost credit products. We find that 32 percent of first-time cdcb clients hold at least three active accounts with a predatory provider. These providers are constantly evolving, building financial empires by tempting consumers who can least afford to pay under the guise of assimilation into the financial mainstream. As a result, our participants’ financial cholesterol levels, or household debt, clog their financial arteries. They spend $548 on monthly debt payments on average, with an average of three to four accounts currently past due. Half of all clients hold more than $500 of current medical debt, resulting in an average net worth of $-17,000. We see families that spend a lifetime living in the red, continually facing recurring liquidity constraints.

Policy recommendation: Reform federal policies such as the Community Reinvestment Act to incentivize large financial institutions to invest capital in Community Development Financial Institutions in order to expand their capacity to lend to low- and moderate-income individuals. This would help expand the provision of helpful products like the CLC alternative small-dollar loan.

Problem 6: Families’ financial safety nets are intricately woven and easily entangled by forces outside their control.

Family networks are an extremely valuable resource within low-income communities of color. In places where access to reasonably priced credit is limited, individuals with strong credit profiles often become a financial anchor for their immediate and extended family. In his groundbreaking work The Hidden Cost of Being African American, Tom Shapiro describes the transformative power of “head start” assets often observed in white families. These include an inheritance that is transferred from one generation to another that facilitates the acquisition of assets. Among many of the low- and middle-income working Latino families we serve, the transfer of assets frequently flows in the opposite direction, from children to parents, and represents less of a “head start” than a “catching-up.” Assets are also transferred horizontally within the same generation, as siblings provide capital and credit for each other.

The unintended consequences of relying on family and friends to take out emergency loans, or to serve as co-signers on cars, large appliances, and student loans, are often not understood. Unfortunately, we have seen parents become unable to access a basic FHA loan because, for instance, they cosigned $40,000 in student loans for their daughter to study medical billing, and now she’s earning $8 per hour, unable to make her defaulted loan payments, thus rendering her parents unable to secure that loan to purchase a home. Similarly, we have witnessed young aspiring professionals, nurses, and teachers, who apply for a mortgage loan, only to discover that they have the all-too-common mixed credit file because they share their parent’s name, or that someone in their immediate family used their Social Security number to access credit unbeknownst to them. This is the perilous and financially unhealthy practice of ‘SSSNACking’ (SSNAC: sharing Social Security numbers to access credit).

Policy recommendation: Amend federal policies to restructure the impact of cosigning on investment loan products such as student loans in order to allow parents to support their children’s educational aspirations while protecting their own credit profiles.

Problem 7: A lack of access to culturally relevant bilingual financial literacy education.

Individuals often seek assistance or guidance to maneuver financial transactions when a negative impending event such as the loss of a vehicle, eviction, or foreclosure is about to occur. As a community, we endeavor to provide individuals with access to opportunities to develop the knowledge and skills necessary to navigate the increasingly complicated financial marketplace while simultaneously providing access to sound financial products and services as well as policies and programs that encourage and support financial health for low-income households. Although many states across the nation have enacted policies requiring financial literacy education for all high school seniors, in many cases the curriculum is not relevant to the lived experience of low- and moderate-income students of color and requires modification for successful integration, adoption and application.

Policy recommendation: Implement culturally relevant financial education curriculum for low- and moderate-income individuals.

Problem 8: A lack of critically important health and retirement benefits.

In our community, women’s labor force participation trajectory is less linear than that of their male counterparts. Women often have gaps in participation in the formal labor market due to the caregiving responsibilities they bear for children or elderly parents. They are frequently concentrated in low-wage caregiving professions, such as day-care assistants or home health providers, often working more than full-time but scattered among various employers without health and retirement benefits. Of households led by single women with children, during 2018 64 percent reported earned income from work, yet lacked federally mandated health insurance. Ninety-one percent of our pre-purchase clients are working at least full-time, yet only 14 percent have access to employer-provided benefits. We are witnessing generations of low-wage earning women of color aging into poverty on account of the fact that although they worked during their prime income earning years, they did not have access to employer-provided retirement benefits.

Policy recommendation: Create a statewide retirement-sponsored savings program, similar to those in California and Washington, that provides individuals with opportunities to save for retirement irrespective of their employer. This would benefit Texas women in particular.

While the above-mentioned statistics are sobering, acknowledging this information about our city’s baseline financial health metrics is necessary to inform solutions, with the goal of treating the root causes that contribute to financial health and wealth inequality in our community. While some people might be discouraged by the scope of the problem or feel paralyzed because they are unable to have an impact on individuals and families beyond their immediate circles of influence, we intend to document the intricate details of clients’ financial lives, actively engage with financial household data, and use this information to identify the critical points within a household’s lifespan where we can invest in the equitable development of its financial health, wealth, and resilience. Furthermore, we look to create innovative financial products and services that meet clients where they are and influence the development of federal, state, and local policies that facilitate wealth accumulation for low-income households.

The services cdcb provides to individuals experiencing economic distress have produced positive outcomes during the last fiscal year, such as an average 5 percent reduction in debt-to-income ratios and $106 in monthly mortgage payments, and an average increase of 82 points in FICO credit scores and $4,898 in savings.

We are now witnessing the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on the financial and physical health of women of color throughout the nation, and of Hispanics, specifically, in Texas. As of this writing, Cameron County is ranked fourth out of the 254 counties in Texas in terms of active cases.1Texas Health and Human Services Department. Texas Case Counts COVID-19. See source. The two local hospitals are beyond capacity, health care staff are in short supply, children await a full return to school, and families remain financially stressed as they shoulder the economic impact of COVID-19. During the initial month of Texas’s shelter-in-place orders, major metropolitan areas throughout the state were able to quickly mobilize and deploy resources to organizations poised to assist individuals with immediate needs. However, Brownsville lacks access to large local foundations with the capacity to raise and allocate similar resources. Perhaps one positive outcome of the liquid natural gas and SpaceX developments could be an endeavor to create a local community foundation specifically designed to expand the capacity of local organizations to build families’ financial health and wealth. In the meantime, we pledge to continue to own more than we owe, to treat the root causes of the cycle of chronic financial illness, to know our financial health numbers, and to live within our means. cdcb is striving to change the intergenerational wealth trajectories of families in Brownsville through the provision of affordable housing and sound financial products and services, while influencing the development of equitable local, state, and federal policies.

Biographies

leads the Financial Security program team and is responsible for overseeing cdcb’s financial sustainability and wealth-building initiatives. Her role includes the planning, coordination, implementation, and evaluation of several financial capability programs, including housing counseling, financial coaching, financial literacy education, VITA tax preparation, and IDA [Individual Development Accounts]-matched savings. She has extensive experience in program and product research, design, and evaluation. Prior to joining cdcb, Diaz-Pineda conducted financial services research, program development, and policy analysis at the Institute for Assets and Social Policy, the National Council of La Raza, and the Texas State Senate. She received her master’s degree in social policy from Brandeis University, and her master’s degree in public affairs and bachelor’s degree in government and Mexican American studies from the University of Texas at Austin.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.

Note: Josué Ramirez, one of this report’s editors, is currently an employee of cdcb.