Between art and architecture

Olalekan Jeyifous speaks about his path from architecture school to the art world.

April 21, 2020

Crown Ether, a public art project by Olalekan Jeyifous that was commissioned for the 2017 Coachella festival. Credit: Lance Gerber

Brooklyn-based artist Olalekan Jeyifous studied architecture at Cornell University and ran a small firm for several years before transitioning full-time to an art practice. The League’s Sarah Wesseler spoke with him about the relationship between art and design in his work.

*

Can you walk me through why you decided to become an architect, and then how you transitioned into art?

I was one of those few people who wanted to be an architect since I was around five years old. My mom would take me to the public library and we would check out books on Japanese architecture, Italian architecture, Danish architecture—all these really big, fun, colorful coffee table books. I believe my mom wanted to be an architect, but for her generation it didn’t seem feasible.

So I arrived at Cornell University thinking that architecture was just about drafting and designing buildings. But Cornell’s program is incredibly conceptual; it’s not only about producing design solutions, which really differentiates it from the more practical or traditional schools.

I was able to grasp some of the core objectives fairly early on, and really enjoyed the design process. I appreciated the storytelling aspect of my architectural education, which was very much about being given a basic problem to solve, and then developing the conditions for your particular program. For instance, if you were designing a hotel and auto body shop, you would develop the parameters and then create a narrative that would explain your concept. It’s not just about satisfying programmatic or spatial requirements; it’s really about developing the story. And Cornell was amenable to students using a variety of techniques for visual representation, like film, collage, technical drawing, and model-making … pretty much whatever you had at your disposal. I personally leaned into that. We would be given a set of requirements for a project—a scale site plan, a certain number of elevations or sections—and I would routinely challenge them. If you could find a better way to articulate your ideas, they would be open to that.

I graduated in 2000 and got a job offer from a corporate firm in Chicago. I thought, “Okay, I’ll do this, because this is the standard trajectory of an architect.” But it wasn’t something that I wanted to do; I just wasn’t sure what else I could do. Fortunately, I was recruited and hired by a company called DBOX, which is run by Cornell grads. Today they’re very well known for developing comprehensive marketing campaigns, along with the visuals and renderings for some of the most well-regarded architecture and development firms, but back then they were producing multimedia for theater productions and fashion, sports, and entertainment publications. My job for the next four years was to create virtual set designs for, let’s say, Victoria Beckham or Michael Schumacher, who was an F1 driver for Ferrari at the time. I was given carte blanche to create exciting visuals for magazine spreads—if I wanted Michael Schumacher to be sitting in a lounge in outer space, I would design the whole scene around however he’d been photographed in the studio.

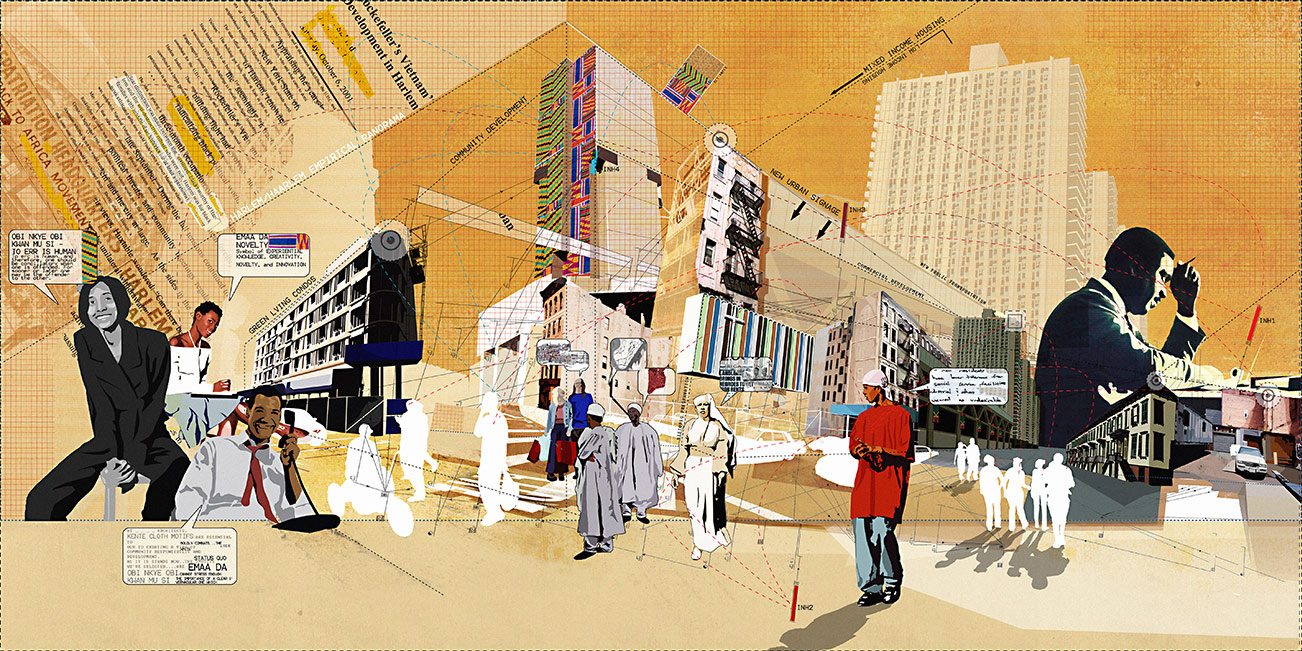

So I did that for four years, until I was invited to participate in an exhibit at the Studio Museum in Harlem called Harlemworld: Metropolis as Metaphor. The curator asked 15 black architects to examine how the neighborhood had changed over time. I created four large collages that revealed the evolution of Harlem over the years and through a variety of scales, from the transatlantic slave trade to the original Dutch settlers and its eventual, and ongoing, gentrification. It was the sort of pre-design due diligence that an architect would perform for a particular project.

I really enjoyed that experience—I liked the immediacy of art, being able to visualize my ideas very quickly. I saw an opportunity to structure an art practice around my architectural education and design process.

I quit my job at DBOX in 2004 to pursue art full time. My early work was rooted in the conventions of architectural representation: plans, elevations, sections, and models. But over time, I was able to move away from feeling like my work had to be architectural in that sense. I started really looking at speculative imagery, experimental animation, and then, more recently, into large-scale public art, which constitutes the majority of what I do now. I’ve been able to balance large-scale public art and exhibitions.

Jeyifous's Grand Rapids, Michigan, sculpture The Boom and The Bust considers issues of inequality and housing discrimination. Credit: Bryan Esler

But you also had a traditional architecture practice for a few years, right?

Yeah. So after 2004 I managed to build up an art practice to the point where I was included in some fairly high-profile exhibits. Instead of bartending or working some other part-time job, I was fortunate enough to be able to do freelance architectural renderings, which gave me tons of flexibility and also sharpened my photo-real visualization skills.

But when the subprime crisis hit, a lot of my freelance work dried up. Almost all of my friends who were practicing architects got laid off at this time, so a few of us decided to start an architecture office. From 2008 to 2012 I had a practice called Freeform Deform with two colleagues. It was your standard small shop: renovations, residential projects, a restaurant, an office space or two. One of my colleagues is still running it, with much more success than when it was the three of us.

Starting an architecture practice is always incredibly difficult, but especially at a time like that. I also realized definitively that I am not cut out to wake up and go to a nine-to-five in any shape, form, or fashion, whether the company is my own or someone else’s.

So in 2012, I made a very heavy push to create more architecturally inspired artwork. These were self-initiated exercises—I was just like, “I have to produce new work really quickly to get back into being an artist full time, and I have to apply for artists’ residencies and as many other art-related opportunities as possible.”

Did you get anything from running a practice, other than the knowledge that you don’t want to do it again?

It definitely had value. My colleagues were both good architects in very different ways, and feeding off of them was helpful. I’ve always been a more conceptual, schematic guy, and one of the other guys was very much into materiality and form, while the other was into big ideas. I got to see many sides of design within a very small practice. It absolutely informs the work that I do today.

The architectural sensibility is especially applicable in public art; some of my projects are basically architectural follies. And my colleagues continue to be a resource when I need to put together a construction budget or work through some of the structural elements for fabrication. It’s interesting when I hear other artists’ frustrations about how to translate their sketches or place their artwork into the context of a physical site—because I have an architectural background, I can do much of that very easily and quickly.

Also, public art is similar to architecture in that there are clients, there are neighborhoods, there are community boards. There are many different individuals and partners invested in what you’re producing that you have to have conversations with. There are also budgetary constraints, material constraints. So having done that for years, I’m very familiar with that type of process.

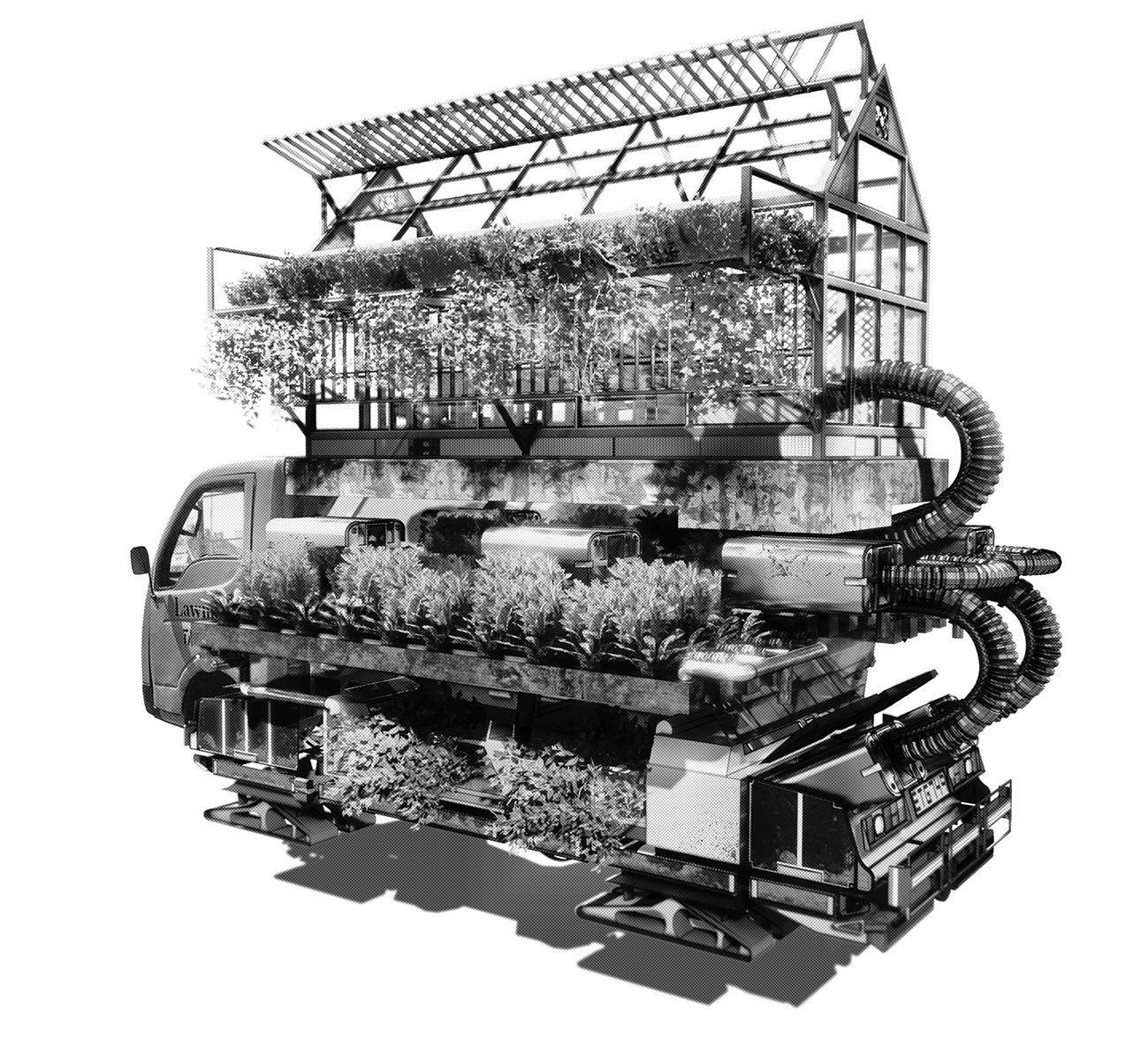

I’m curious about your ideas around accountability to the public at large, or to particular communities, when moving between the art and architecture worlds. Your Shanty Mega-structures project, in particular, has won a lot of praise in some quarters but been heavily criticized in others. Can you talk about how people have reacted to that project, and how you think about it in terms of the artist or architect’s professional responsibility?

That’s a great question. In the popular imagination, there’s this idea that architecture solves problems, or is supposed to. But as an artist, you’re sometimes more interested in challenging ideas—in intentionally making implausible architecture, for instance. So you can get into trouble depending on how the project is framed.

For Shanty Mega-structures, I made it very clear when I put it out into the world that this was not a design solution; this was not intended as a serious architectural proposal. Instead, I saw it as a visual critique of large-scale urban development and how it erases marginalized communities all over the world, not just in sub-Saharan Africa.

When I talk about it, I always show pictures of housing projects in Chicago that were torn down and their inhabitants displaced. But what made it interesting for me to think about Lagos, Nigeria, was the way the informal architecture there is constructed and organized. So my concept—and I made it very clear—was to reimagine this informal building typology at a massive scale, since large-scale urban development usually means luxury office towers and residential properties. Marginalized communities are at best ignored and at worst demolished to make way for these developments.

Also, I’m very much inspired by science fiction, so I wanted to create a sci-fi world around informal settlements in Lagos, thinking about how they could eventually overrun the prevailing architectural landscape, extending hyper-visibility to these communities.

But it doesn’t matter how I explain the project. It’s been presented in so many ways; people will simply ignore what you say, especially if it’s seen as an architectural intervention. I show this work quite often in academic spaces and lecture on it in architecture schools, and some of the audience really wants it to be an earnest design proposal. When it was published, regardless of what I said about the work, editors would go with a clickbait title like, “Is this the new skyline for Lagos?”

So I’ve received my share of criticism. I’ve also made a point of exhibiting and showing and discussing the work in Nigeria, and I got eviscerated by one of the students at the architecture school at the University of Lagos. She was almost in tears, she was so offended. I’ve even had people on Twitter message me and say, “You’re creating ruin porn for the consumption of Western media. You’re making us look bad. This is not the future of the Lagos skyline. You obviously didn’t grow up here!”

It’s interesting—oftentimes, what I’m trying to do in my more speculative work is not to romanticize poverty, but challenge the idea that systemic issues can be resolved through good design alone. Many architecture schools have these studios that focus on designing affordable housing or emergency shelters for the displaced. This can be useful as a design exercise, giving students hands-on experience and instilling a sense of social responsibility. But it can also create false expectations, and even give architects a sense of paternalistic entitlement as to the impact of their work.

This can be especially problematic when you’re designing for marginalized communities, because projects often succeed or fail based on issues that aren’t fundamentally architectural. For instance, even the most well-intentioned design project can languish and fall into disrepair when a community doesn’t have the resources to maintain it.

So architecture can’t solve every challenge—public policy and infrastructure also play crucial roles when you’re talking about issues like affordable housing, post-disaster housing, etc. But in the public imaginary, there’s a pervasive belief that just by making certain types of architecture—housing, schools, hospitals—you can resolve systemic problems.

For me, art can be that tool for reflecting on the ways that architecture can actually exacerbate problems in the absence of broader systemic changes. In my work, I’m more interested in inventive, speculative ideas as a vehicle for social critique, or as a way to expand dialogue and engagement with certain socio-economic, environmental, and political realities.

Interview edited and condensed.

Explore

Ursula von Rydingsvard lecture

Artist Ursula von Rydingsvard's hands-on, physical working methods and intuitive approach to monumental form-making are illustrated through a series of recent projects.

Forms of aid: Architectures of humanitarian space in Nairobi, Kenya

Benedict Clouette and Marlisa Wise write about urban and architectural consequences of international humanitarian operations.

Hiroshi Sugimoto lecture

Sugimoto, a renowned photographer, explains his turn toward architecture.