An Urban Lifesaver

Dreaming of a new relationship with our cities, Erik Carranza of Anonima designed a game to bridge the gap between children and the urban environment.

Erik Carranza is a 2024 League Prize winner.

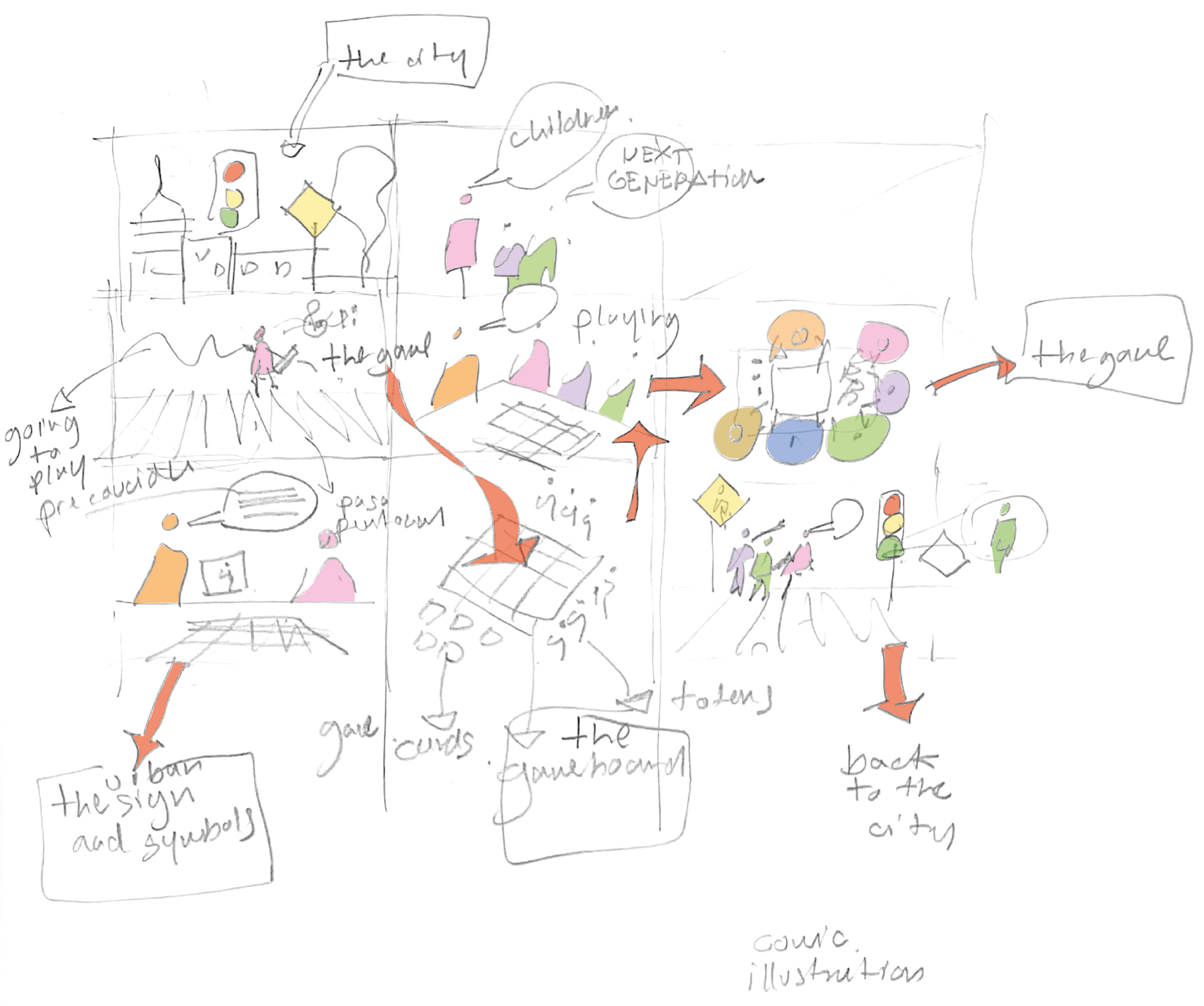

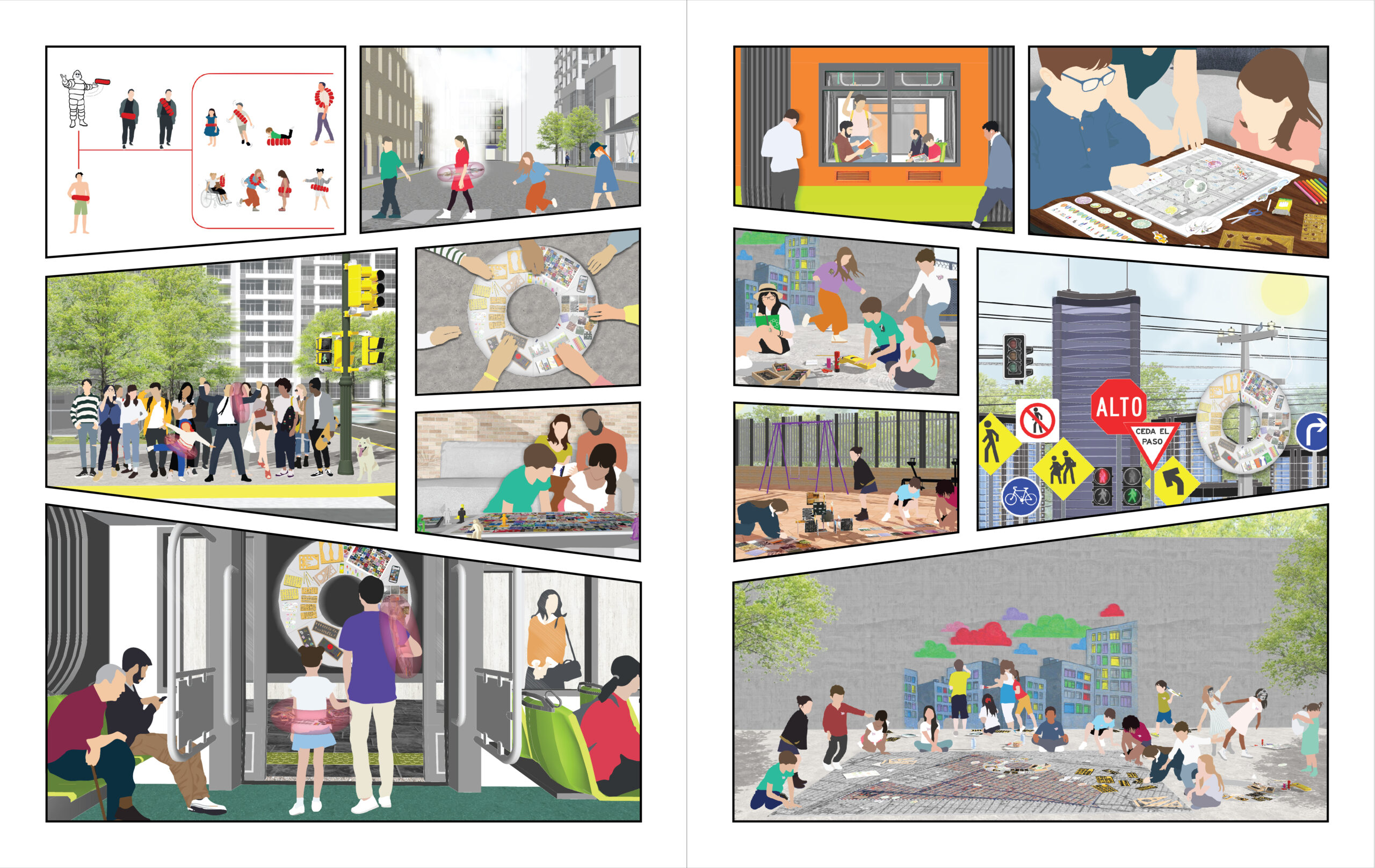

Erik Carranza founded Anonima with Sindy Martínez Lortia in 2007. Based in Mexico City and Oaxaca City, the multidisciplinary studio engages in both design and research projects related to urban spatial practices, ranging from street-level interventions to institutional built work to advocacy campaigns. For his League Prize installation, The Architect’s New Dream, Carranza and Anonima designed a game that empowers children to relate to the city on their own terms and at their own scale.

League staff member Alicia Botero spoke with Carranza about the inspiration for the game and balancing the studio’s “reverence for the past” with “references toward the future,” in Carranza’s own words.

*

Alicia Botero: What did the process of developing the installation look like?

Erik Carranza: The installation came into being with the question of the body and how we represent it, not just in architectural terms but also in the cityscape. How do we read those bodies that at some point become a sign and even a mode of communication?

The first idea we had was to revive our Instagram account, which is a compilation of images of the city which reference bodies, proportions, ergometry, anthropometry, how architects represent bodies, how bodies are represented in other disciplines, and even of the wealth of symbols that exist behind all these representations.

If one approaches, for example, Ernst Neufert’s Architect’s Data, one notices that women are represented in only a few pages and [only doing] certain activities: in the kitchen, in the supermarket, in cleaning spaces. This has a series of historical repercussions for the education and production of architecture with a perversity that we can’t even begin to measure or understand the dimensions of. We ask ourselves about this constantly: How valid are these situations, these references, and these authors in the current time? Is part of historical “dirtiness” our continual use and citation of them? Don’t we need something much more closely linked to how we are currently living, new lines of investigation that hold [different] perspectives on gender, identity, and other representations and discourses?

So we began with a very vague and basic idea of doing this recompilation of images not only from our Instagram account but revisiting certain authors and their repercussions in the architectural medium. We wanted to assemble the content through the curation of a “Museum of the Human Scale,” a revision of how we have represented ourselves throughout time, given the fact that spatial perception is tied with the representation of the human scale.

We weren’t happy with the result because it was too much information and required too much production and management, and in Mexico City it isn’t easy to find exhibition spaces at the scale we were imagining.

Suddenly, amid these reflections and dreams, I remembered having read somewhere a quote “…as important is Palladio as a morning’s first coffee.” When I searched for it, I did not find it. But I remembered where Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi make that reference, which is in the reinterpretation they do of Thomas Cole’s The Architect’s Dream. Beginning again from there, we began to document and describe that “dream,” trying to understand the references, the architecture, and even the books on which [the architect] Ithiel Town was sleeping. There we found a symbolic relationship between the reading of the city and how the body is being represented, which was precisely what we were looking for.

We realized that perhaps what we were describing was not a dream [but] more so an architect’s nightmare, because these things—the lack of integration with context, the excess of the graphic, architecture as a symbol instead of as a space—are precisely the elements that combat one another through architectural practice. We thought that from this nightmare we would have to begin generating new readings of those references for future generations and establish completely different communication with the city. This led to our installation: a series of tools to approach architecture and the city from childhood.

Botero: How do you see this toolbox being used?

Carranza: Civics classes already exist, which have to do with the formation of citizenship. We would have to complement them with a class on urbanism, architecture, and the city. To have this sense of a “Primary Architecture,” these wouldn’t be architecture classes as such but classes about the appropriation and appreciation of space for children to begin understanding all that is implicated in these spatial topics. There is, for example, the topic of water, of how to move through the city, of how to identify flora and fauna in the city, there are historic values, cultural values, architectural and urban values, works that are worth preserving.

What we are interested in is precisely what kids are beginning to ask—How is this used? What is it useful for? Can I touch this?—and from there we can begin to generate the conversations we are looking for. For example, the toolbox has a representation of fauna with concrete animals because there was an architect in the 60s who designed these children’s play structures. Seeing the animals, the kids themselves start raising their hands and saying “Yes, I remember,” “In my park,” “Close to my home there’s one that survives.” From those experiences, conversations and discussions emerge. Kids begin understanding how they can read the tools and through the tools the city, how they can begin to develop their points of interest, of identification, of encounter.

We are supposing that in a basic middle school of 100 students, possibly one or two will become architects or designers. But if those two have a basis of spatial perception through these tools, certainly when they must make decisions for the city, for public space, they will do so in a far more conscious way. It is a very long-term bet, but I believe it must be done because of how we are living in cities nowadays: decisions are made without basis, taken from a place of ignorance. There is a lot of destruction of urban, ludic, and architectural patrimony and this is done indiscriminately: it is decided that heritage play sculptures will be foregone, with no criterion, and these are replaced by plastic structures that last three or four months. I understand that there is a process and economic procedure in these decisions which I do not share. I believe economics are not the only factors that should be considered when taking decisions regarding the city.

Botero: I wonder what happens with the other 98 or 99 kids? How do you see this game impacting the population of non-architects?

Carranza: We already put in their perspectives the seeds needed to talk about space, to talk about the city and its importance. Possibly from those 100 none will become a designer, but they already have in their heads this idea that there is something called space, something called body, something called city, that there is architectural value, historical value, and that it is good to question, to talk through and discuss the reasons for things.

For example, we travel sometimes with friends who have young children and at some point, the kids are bored of so much walking and museums and restaurants, of so much adulthood I’d say. So, I started playing “urban treasure hunt” with them. Graffiti can be an urban treasure, or an intervention, or a sticker, or a mistake like a tile that is crooked because the Department of Public Works had to fix something and didn’t care about placing it [in line]. For the kids, a kilometer that could have been boring is converted into a discovery of reading the city. Can you imagine what we could find at the scale of children in the city if they had the spatial basis of a Primary Architecture?

I think this installation brings forward a lot of possibilities. It is a bridge to relate to a city that was not made at kids’ scale, it’s like a dream: suddenly a lot of things seep in, it becomes a nightmare, and it begins to trigger a lot of things in one’s head the next morning, leading to a [realization that] “Okay, I can interact with reality in many ways.”

Botero: I am interested in whether kids in turn impact Anonima’s design process…

Carranza: For us as an office the hierarchy of decisions is: If it works for kids and elderly people, it works for everyone. We take into account the poles of life because we know that in the middle there is a group that is covered by the situations already proposed. We were all children. We will all be elders. And so our design process always has a reverence for the past and a reference towards the future. That is incredibly important in design: to work with a past and future temporality instead of only with the present.

Additionally, our first attempt at sharing projects has always been with kids. We have noticed that adults are very clear on what it is they want, so they might be in favor or against something, always caring for their own interest. An adult will never think of others. Adults are individualistic. Children are collective. They think at different levels and in other scales.

I remember once at a conference I said jokingly that children were amongst our principal advisors at the office because they changed the perspective of things. That comment was a way to break the ice by changing the audience’s perspective. But it has become a methodology. In each project there is a ludic component, be it in the process, in the interaction with the community, or in the design. All these tools can begin to be facilitators for kids to use in the process of designing space.

Explore

Building as BFF? Yes Please, Says Could Be Design

For the Chicago practice, creating playful, accessible architectural experiences is serious business.

Re-envisioning New York’s branch libraries

The Center for an Urban Future's latest policy report provides a comprehensive blueprint for bringing these vital community institutions into the 21st century.

Connective spaces and social capital in Medellín

Jeff Geisinger investigates the built environment's impact on social capital in Colombia's second-largest city.