Africatown, Alabama

Racialization of Space and Spatialization of Race

Architect and historian Craig Wilkins and urban designer and report editor Renee Kemp-Rotan discuss the community’s public spaces and the opportunities that new cultural tourism, focused on a story of African emancipation and autonomy, might have on revitalization efforts. This is a crucial time in the history of Africatown, as many decisions are being made regarding future development, following the discovery of the slave ship Clotilda (the ship that illegally trafficked many of Africatown’s ancestors from present-day Benin to Alabama in 1860). Following an introduction by Wilkins, Kemp-Rotan argues for a reckoning with this history, an embrace of African and Black identity and design traditions, and the development of a comprehensive regional plan of new public spaces, historic and tourist sites, and locations for economic development, informed by a major new design competition.

Introduction: Africatown has an Overdetermined Legacy of Land Loss and Displacement

Access to the benefits of public space is the wellspring from which all other benefits flow like health, wealth, and prosperity, providing citizens opportunities for clean air, clean water, clean land, as well as healthy foods, safe recreation, relaxation, and public transportation. A truly viable, livable community is both socially and economically self-sustaining; however, for it to be just and equitable, no one group, community, or neighborhood should be more burdened with deleterious environmental effects or blessed with spatial benefits than another. Yet, decades of planning and economic research overwhelmingly reveal a long legacy of racism in the policies and practices that shape our shared public realm. In ways overt and covert, implemented on scales large and small, national and local actions frequently disenfranchise, disinherit, or otherwise disassociate Black and brown people from the benefits of public space. The denial ultimately weakens both place and people. It is no surprise Black and brown communities are disproportionally harmed by the current pandemic. A quintessential exemplar of both de jure and de facto institutional racism, Africatown has been—and remains still—intentionally and systemically excluded from conversations, much less remedies, for just and equitable spaces in the state of Alabama. The environmental degradation, devaluation, and incremental encroachment into Africatown’s private and public spaces to serve the interests of industry, corporations, developers, and utilities over its residents represent a deliberate and ongoing taking of spatial resources and benefits.1Learn more about these decisions and their impact on Africatown. They are, in a very real way, acts of thievery that knowingly deny the citizens of Africatown their very basic right to life.

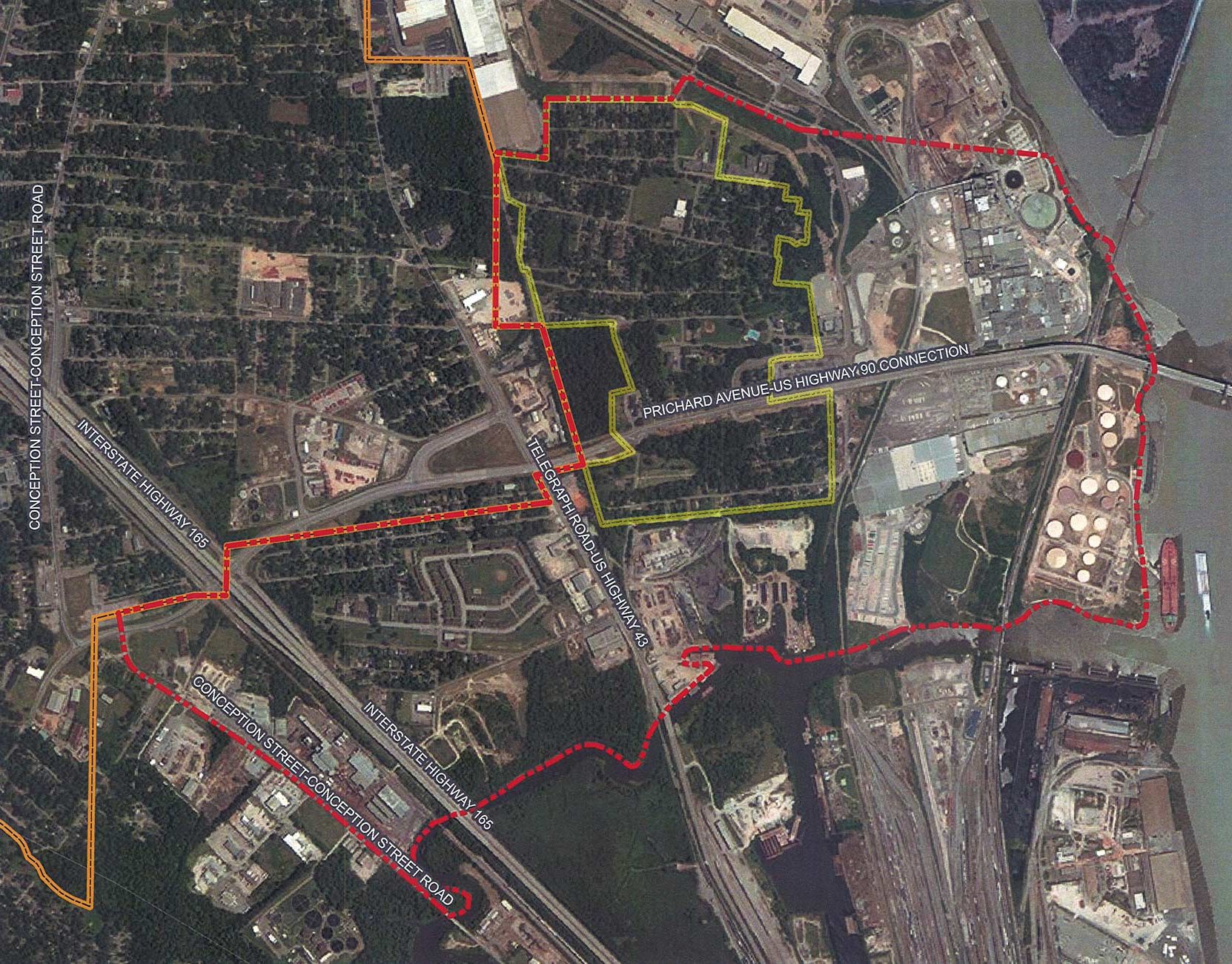

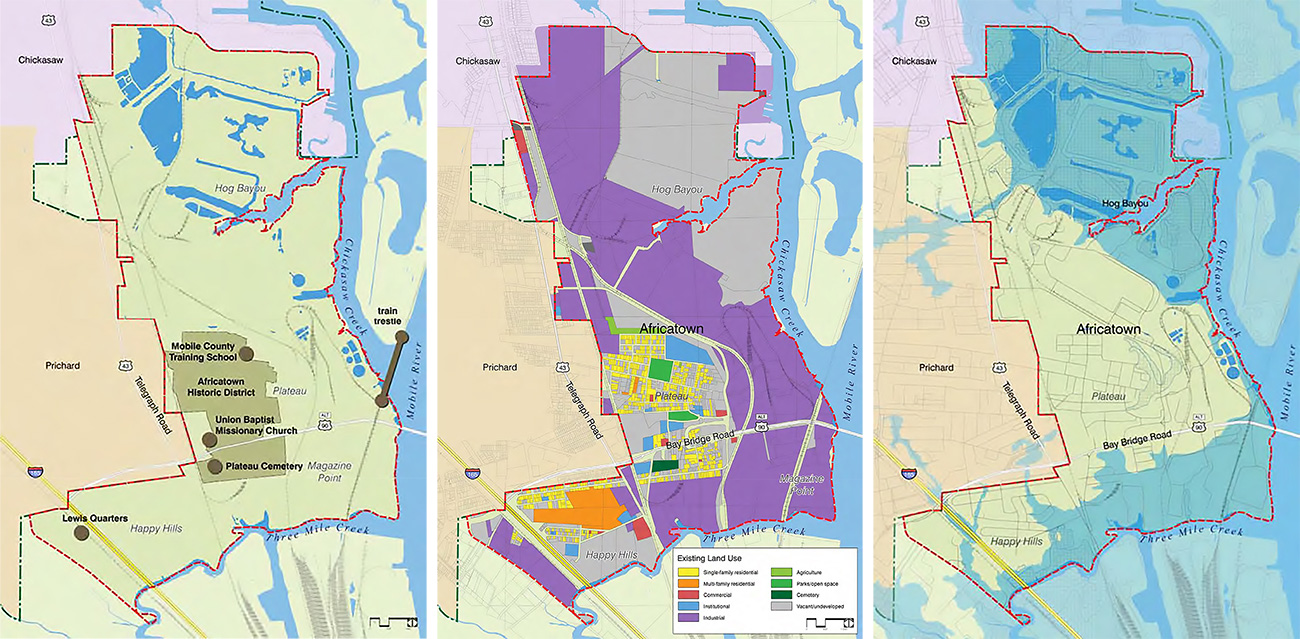

Left: The current historic district and sites of interest. Center: Current land use in Africatown—the historic core of Africatown is in the Plateau neighborhood, now surrounded by industry (purple), which also blocks community access to the water. Right: Much of Africatown’s land lies in floodplains, including a significant part of its industry. Credit: Africatown Neighborhood Plan

A close look at the somewhat irrational boundaries of the historic district reveals excluded historic neighborhoods such as Lewis Quarters that are integral to the Africatown story. A cursory examination of current city-proposed land use changes, zoning adjustments, and zoning variances reveals examples of land loss and displacement tied to land control, land value, and land production in Africatown. Additionally, before the discovery of the Clotilda, city investment in the area was slow and inconsequential. —Craig Wilkins

Part I

Lay of the Land

Africatown is bounded by water on three sides: to the east by the Mobile River, to the north by Chickasaw Creek and Hog Bayou, and by Three Mile Creek to the south. The City of Prichard and Interstate 165 lie to the west. Today, residents complain that, due to industry, they have lost much of their direct access to the water—so important to Africatown’s geopolitical history—where their ancestors once fished, hunted, and swam.

Africatown was originally a 50-acre community, with most of Clotilda’s 30 families living in the Plateau and Magazine Point areas, and a smaller zone two miles to the southwest, the 7-acre Lewis Quarters built by Clotilda descendant Charlie Lewis on land purchased from his former slavemaster Colonel Thomas Buford.

Left: Fishers at Three Mile Creek. Right: Three Mile Creek, close to the site of Lewis Landing #1 on the Africatown Connections Blueway plan. Credits: Vickii Howell

From a population of 12,000 in the mid-twentieth century, with most families employed in nearby industry, Africatown’s population has since declined sharply due to fewer jobs in the nearby factories and the simultaneous encroachment of polluting industry into formerly residential areas. The 2010 US Census records Africatown’s population at 1,881 people, 98 percent of whom are African American. This severe population decline has led to a landscape of vacant lots and neglected properties. As Joe Womack, Africatown native and president/director of the nonprofit Africatown~C.H.E.S.S. (Clean, Healthy, Educated, Safe and Sustainable), points out in a blog post, the number of Africatown neighborhoods decreased from fourteen to seven over time.

Today, there is interest in forming a land trust to reclaim vacant properties in Africatown. One model to follow is the Africatown Community Land Trust in Seattle, Washington, which was formed to acquire, steward, and develop land assets that help the Black/African Diaspora community of Seattle’s Central District grow and thrive in place and support other individuals and organizations in the retention and development of historic land.2While the land trust’s name is inspired, in part, by Africatown, Alabama, the Black community of Seattle’s Central District is not related. Learn more.

Architectural historians have traditionally avoided the topic of race. When they do acknowledge the subject, they often quickly dismiss its significance . . . —Irene Cheng, Charles Davis, and Mabel O. Wilson, editors, Race & Modern Architecture

Africatown: The Historic District

The part of the greater community now deemed a Historic District is tiny, and it is not clear why its boundaries exclude other historic Africatown neighborhoods, including Lewis Quarters. Africatown was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2012, when the community, as the first settlement built by Africans in America, was declared an ethnic archaeological site of national historic significance.3Read the full National Register of Historic Places nomination. The nomination report also cites the community’s unique paper trail of documents, naturalization papers, voting records, and land sales that together with an oral history kept alive by a descendant community contributes to our understanding of American slavery in nineteenth-century Alabama.

The Africatown Historic District is comprised of 921 acres, containing 455 structures, of which 443 are residential. Of those housing units, 253 are structures that contributed to Africatown’s most significant development stages: Stage 1 (1866-1900), when Africatown was founded, and Stage 2 (1900-1945), when the last land was platted and industrial proliferation and annexation into Mobile began.

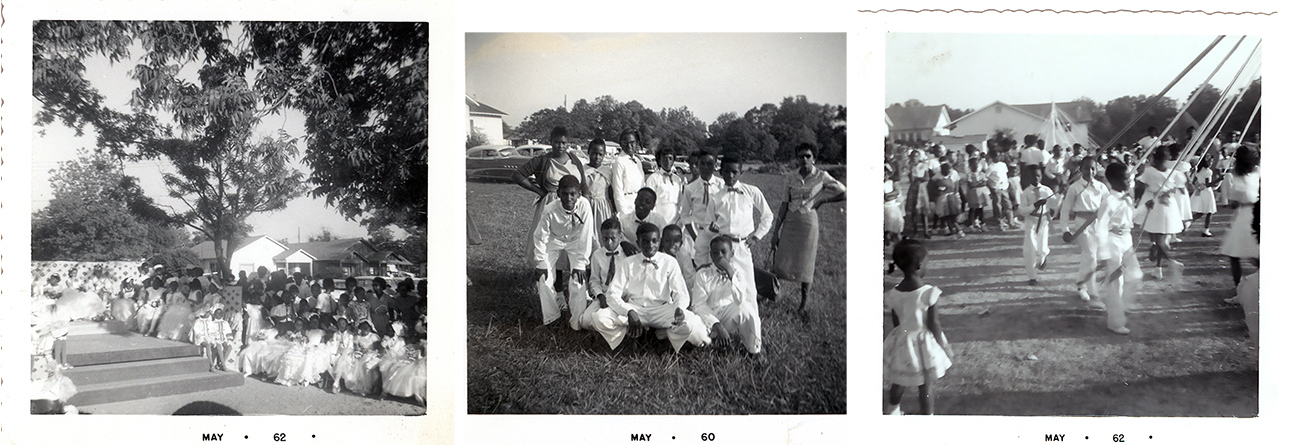

Black Space Matters

The first public places in Africatown were its churches. As historian Natalie Robertson describes, “When blacks built their own facility in which to hold ‘church,’ that building became a focal point of the community, an educational center, a meeting place for political activism.”4Natalie S. Robertson, The Slave Ship Clotilda and the Making of Africa Town, USA (Westport: Praeger Publishers, 2008), 170. The community’s other early public spaces were tied to water and used for baptisms and other sacred community commemorative rituals. These rituals continue to the present, upheld by the descendant families of Cudjo Lewis, Charlie Lewis, Pollee Allen, Orsa Keeby, and Peter Lee.

Creek baptism in Three Mile Creek. Credit: Billy Skipper papers, courtesy of The McCall Library, University of South Alabama.

Today, Africatown has several parks and green spaces that serve the small community, including John Kidd Park with its swimming pool; athletic fields for baseball and track adjacent to the Rev. Robert Hope Community Center; and the Mobile County Training School with its recreational yard and Community Memorial Garden Wall. These outdoor open spaces host important community events, including the Spirit of Ancestors Festival, Community Day, the Ringing of the Bell, Sites of Memory commemorations, annual kite-flying contests, and swim and scuba classes for children. These sites—along with historic spaces such as the Africatown cemetery (where headstones have been recently toppled)—must be uplifted, protected, maintained, and reinvigorated by historians, architects, artists, and cultural archaeologists, in partnership with a descendant community that wishes to preserve the spirit of these sacred places.

Part II

The African View of Land in America

Africatown’s land is important not only for its specific uses, but also as a symbol of the community’s autonomy. In Africa, communal land for subsistence was owned by the tribe. Robertson writes, “There is no subject in which the Yoruba man is more sensitive than that of land,”5Natalie S. Robertson, The Slave Ship Clotilda and the Making of Africa Town, USA (Westport: Praeger Publishers, 2008), 141–142. which explains why after the Civil War, Cudjo Lewis (known as Kossola in Yoruba), one of Africatown’s founders, sought land on behalf of his fellow Clotilda Africans from their former slavemaster Timothy Meaher.

Complicating these land sales to the Clotilda Africans was the 14th Amendment, which conferred citizenship and thus the ability to buy land only to persons (including ex-slaves) “born or naturalized” in the United States. But, the newly emancipated Clotilda shipmates were born in Africa. In order to buy land in America, they first had to become naturalized citizens, and they did. The Clotilda Africans were well organized, studied the rules, became citizens, and then helped each other buy land, build houses, and create a community. In this founding of Africatown, they brought their West African agricultural, cultural, technical, and spiritual knowledge and skills to build a self-contained, self-governed, and self-sufficient community.6Natalie S. Robertson, The Slave Ship Clotilda and the Making of Africa Town, USA (Westport: Praeger Publishers, 2008), 141–142. As Robertson writes, “Africatown is a study in transference and application of ancestral genius and indigenous knowledge.”7Natalie S. Robertson, The Slave Ship Clotilda and the Making of Africa Town, USA (Westport: Praeger Publishers, 2008), 158.

The building of Africatown was an effort to preserve and protect indigenous language and customs on autonomous land. As communally as possible, the founders built 30 small houses on approximately 1.5 square miles. They formed their own colony that afforded them vestiges of communal living, such as farming and the sharing of food, much as they had done in Africa. Africatown as a physical settlement was a place to keep outsiders—both white and African American people, who teased them for being different—out.

In this way, historian Sylviane Diouf contends that “[t]hey were Africans internally and externally. Internally because they had used their Africanity as a cement transcending cultural differences, externally because, to outsiders, they were all the same, Africans, with the negative connotations the term often implied.”8See source.

The Architecture of Africatown

“Broadly speaking, the major African architectural contributions in America were primarily [in the areas of] response to climate and use of materials. Slaves coming to the New World had a familiarity with natural materials like sun-dried brick and they had exceptional skills at carving wood, making plaster molds, working iron—and these techniques soon had an impact on how everyone was building,” notes architect and architectural historian Richard Dozier in an interview in Blueprints magazine.9Martin Moeller, “African Threads in the American Fabric,” Blueprints.

Most of the evidence we have today for the study of plantation buildings and spaces is housed in the National Park Service’s Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS). In the HABS collections, drawings of slave cabins, kitchens, barns, stables, and other slave workplaces reveal the building knowledge that these enslaved Africans possessed.10John Michael Vlach, Back of the Big House: The Architecture of Plantation Slavery (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1993), XI.

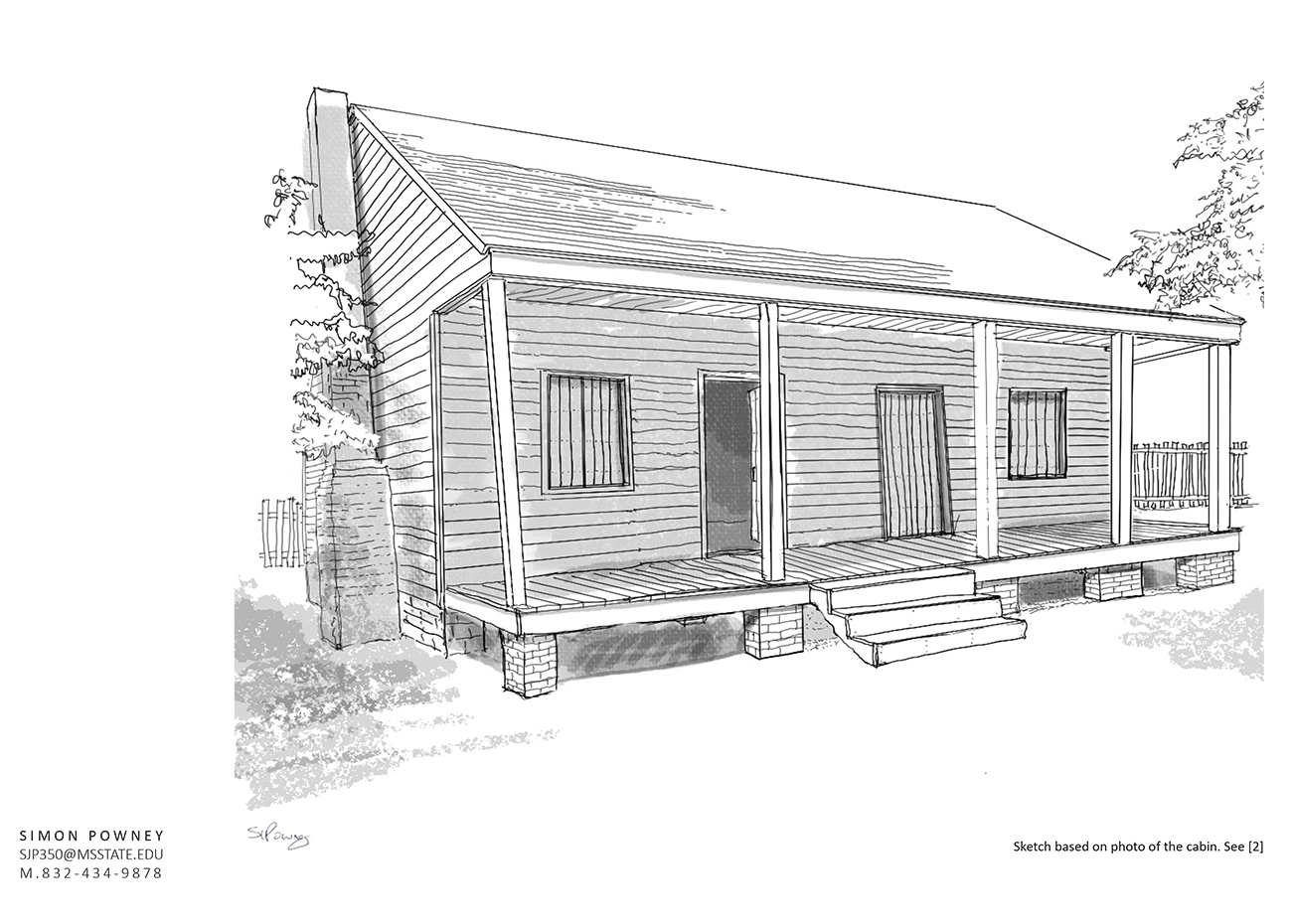

Once emancipated, the Clotilda Africans built log cabins and shotguns. Though much of this original Africatown settlement is now gone (perhaps one 1870 cottage still stands, per the National Register of Historic Places nomination report; today, the community consists of modest shotguns, bungalows, and Victorian- and Craftsman-style homes, built mostly from 1900-1960), a few sites point to African cultural influence that the founders likely brought to the community.

One extant piece of Africatown’s architectural history is the mortared chimney from Africatown cofounder Peter Lee’s original nineteenth-century house. Lee’s African name was Gumpa, from the Fon language. He was an African prince—of the Fon tribe, the ethnic majority of the Kingdom of Dahomey (now Benin)—given as a “gift” to the captain of the Clotilda. Because of his royal lineage, the dispossessed Clotilda Africans elevated Gumpa to the status of Africatown’s judge. His house, therefore, sat on a small hill above the other homes as a sign of his leadership among his Africatown people. While his house with the brick chimney is not African in construction, its placement on an elevated site is in accordance with African respect for his station as an elder.

Most buildings in Africatown exhibited a strong sense of architectural assimilation with the dominant culture of Alabama. If one were expecting to see an “African village” with mud huts, you would have been sorely disappointed. However, many architectural elements, while not blatantly African at first glance, have symbolic value.

I have seen this in my work on The Cudjo Lewis Blueprint Initiative, a project sponsored by the Alabama Historical Commission that seeks to reconstruct Lewis’s house from photographs and oral histories. We have found that Cudjo’s house was a wooden log cabin with a porch, a courtyard, a well, a garden, and gates. This compound was developed by purchasing lots adjacent to one another. While the log cabin is not African, specific aspects of the house recall African cultural and architectural concepts.

Cudjo’s Gates of Oyo to Protect Homestead Boundaries

The great West African empires of Dahomey, Benin, and Oyo that birthed Cudjo Lewis are known for settlements with systems of gates and walls for security and protection against warring tribes. Natalie Robertson has noted that Cudjo surrounded his house with an eight gate wall system. Her research suggests that Cudjo was from the royal farmland of Owinni outside of the city of Oyo, which originally had nine gates: eight gates for the toll keepers and one gate for the Basorun tribal authority. Cudjo would have respected the restriction of the ninth gate by omitting that gate from the enclosure that he built around his house in Africatown. These eight gates helped to define Cudjo’s property and courtyard. They also delineated his property from that of other African housing sites and public communal spaces.11Natalie S. Robertson, The Slave Ship Clotilda and the Making of Africa Town, USA (Westport: Praeger Publishers, 2008), 93—95.

African Building Traditions and Afro-futurism

John Michael Vlach’s Back of the Big House: The Architecture of Plantation Slavery; Mario Gooden’s Dark Space: Architecture, Representation, Black Identity; Jack Travis’s lifelong collection of African architecture forms and pattern making; the African architectural design research of David Hughes and Nigerian planner Nmadili Okwumabua; and the architectural projects of Sir David Adjaye and Francis Kéré teach us to respect the three-dimensional prowess of our ancestors and their knowledge of “the building of things.” From historians of African architecture in America like Dr. Dick Dozier and practitioners like Phil Freelon and Max Bond, we are learning a new respect for the preservation and promotion of the aesthetic values developed by Black builders, architects, planners, and urban designers.

Now is the time to imagine Africatown as Afro-futurism by design, as a site that could drive cultural expectations towards a new creative African placemaking experience that attracts millions of visitors and millions of investment dollars to transform Africatown into a new kind of utopia—a well-designed and well-curated billion-dollar revenue generator for Africatown, Prichard, Chickasaw, and the greater Mobile region.

“Remember Black Panther. Think Wakanda for Africatown. African communities must have African forms.” —Jack Travis, jury chair, Africatown International Design Idea Competition

The Porch: To Delineate Public from Private Spaces

According to scholar James Deetz, author of In Small Things Forgotten, the porch did not become a ubiquitous feature in the American South until the late eighteenth century, when slaves were building shotgun-style houses from patterns derived from their West African heritage. There is evidence that even the word shotgun might come from the word “to-gun,” from the Fon people, which translates to “place of assembly.”12Alyson Fletcher, “The American Porch, by Way of Africa,” Blueprints. Dozier further explains: “In the South, of course, we can attribute the domestic porch to African influence in response in part to climate. In African village life, shared space—courtyards, etc.—was important. And shelter from the heat was obviously important. In America, these things came together in the porches that we now take for granted.”13Martin Moeller, “African Threads in the American Fabric,” Blueprints, 2.

The Well

Gary Lumbers, a descendant of Cudjo Lewis, lived a majority of his young life with his grandmother in a home that incorporated Cudjo’s original house as its living room. He recalled that the property had a well in the backyard that had been covered over for safety. It was no longer needed since the new house had plumbing. But the well would have been significant for Cudjo. Robertson writes that “Cudjo dug a well from which he drew water, characteristic of the wells and boreholes that Africans dig to access water across the continent of Africa. Thus, in Africatown, Cudjo designed his property as a West African influenced, eco-balanced, sustainable farmstead that provided shelter, food, and water, thereby, promoting self-reliance and self-sufficiency.”14Natalie S. Robertson, juror essay for the African International Design idea Competition Book, publication forthcoming.

Public vs. Private Space

In the case of Africatown, the founders built their houses close to one another, as was true in the typical West African compound. In the United States, they transferred their African knowledge of the shotgun house, porch, yard, and gate. Though they separated themselves from both whites and African Americans to preserve their customs, when it came to housing forms, they built log cabins and their own invention of the rectangular shotgun, as they did not want to stand out. For cultural assimilation and communal public life, they further built the church, school, and cemetery. Yet privately they imbued these spaces with African meaning and incorporated African details recalling their homeland.

They lived the two lives of Africans in America: what W.E.B. DuBois calls the African skill of double consciousness.

Part III

Fighting the Good Fight for Clean Neighborhoods and Clean Tourism

Africatown and the historic spaces it contains have been ignored for generations by many powers that be. Today, Africatown residents are fighting to be seen, to be heard, and to fully participate as co-partners in the community development process. A thorough clean-up of Africatown’s public spaces will enable the promotion of clean tourism.

Mobile Environmental Justice Action Coalition (MEJAC) was formed in September 2013 to engage and organize Mobile’s most threatened communities in order to defend their rights to clean air, water, soil, health, and safety. MEJAC is a democratically organized, very-low-budget, all-volunteer, yet passionately engaged grassroots organization, taking action where government has failed to do so and, in the process, ensuring community self-determination. Several members of MEJAC formed C.H.E.S.S. (with support from the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice) to be its local, community-based organization working to resist environmental racism and bring additional resources to Africatown through a grant from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

The community is fighting against:

- continued plans to build oil storage tanks and to expand operations of other petrochemical-related industries,15Learn more. and

- rezoning changes outlined in the Unified Development Code for Mobile that fail to adequately use green buffers and setbacks to protect the community from industrial proliferation in residential areas.16Learn more.

The community is fighting for:

- Federal grants to support the Africatown Heritage Preservation Foundation’s collaboration with the National Park Service to imagine and build an Africatown Connections Blueway,

- the success of Mobile’s federally funded Brownfields Study, which includes environmental assessments of 22 sites in Africatown,

- preservation and ongoing capital and maintenance funding for the historic Old Plateau Cemetery as Africatown’s most significant historic public open space and as one of the most significant African burial grounds in America,

- a farmer’s market, supported by one of the first grants awarded under a statewide program to provide incentives to develop, renovate, or expand grocery stores and markets in communities with limited access to fresh, healthy food,

- future zoning that supports more green space and access to the water through the Africatown Connections Blueway project,

- the Cudjo Lewis House Blueprint Initiative: a project supported by an Alabama Historical Commission grant to assemble Zora Neale Hurston’s photos of and interviews with Africatown co-founder Cudjo Lewis in order to develop blueprints for re-construction of his home as a small museum17Learn more. about the making of Africatown, and

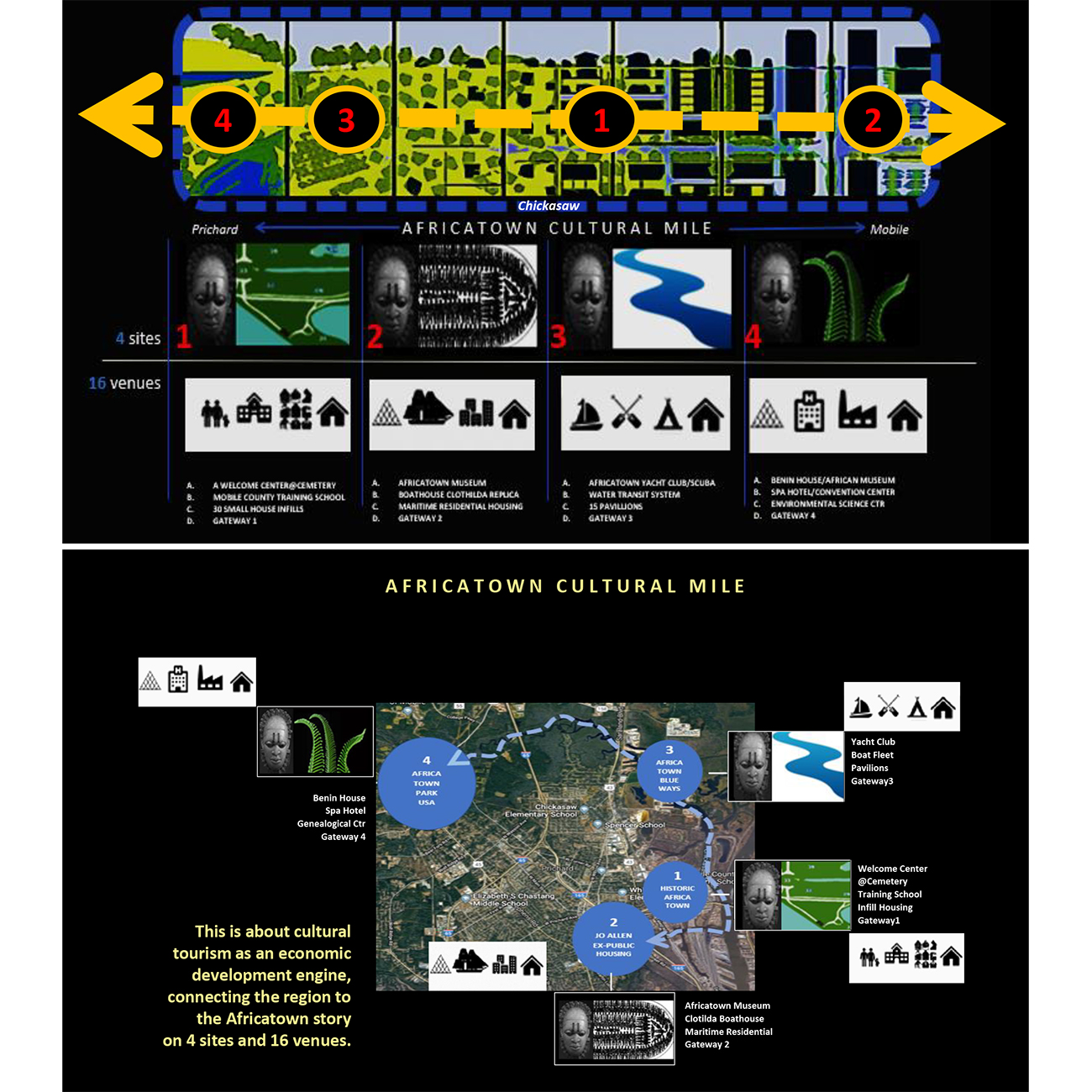

- full funding of the 2021 Juneteenth launch of The Africatown International Design Idea Competition, with its concept for immersive multi-site public memorials and interpretive sites along The Africatown Cultural Mile, a new initiative to connect the many places of Africatown’s history.

Left: Current land use in Africatown. Right: Proposed land use in Africatown. Credit: Africatown Neighborhood Plan

Throughout the years, community development organizations such as MEJAC and Africatown~C.H.E.S.S. have reached out for legal and design assistance in their zoning fights to supplement the 2016 Africatown Neighborhood Plan, the current foundational blueprint articulating the community’s needs, which was commissioned through the City of Mobile’s Neighborhood Development Department. These groups seek to capture and organize the collective thoughts and wishes of Africatown’s residents about what they want their community to look like in the future.18Many organizations have come to their aid for zoning and environmental issues. Likewise, many universities responded by working with the community to produce various public space ideas through workshops, design charrettes, field surveys, oral histories, photos, and film. These include Mississippi State University, Auburn University, Oberlin College, University of Oregon, the University of South Alabama, and Spring Hill College.

Additionally, several Africatown leaders are working to build up the Africatown Heritage Preservation Foundation, an umbrella organization designed to advocate, raise funds, and act as a clearinghouse for all things Africatown in the historic community,

While all have worked tirelessly, few have connected all the sites, something so necessary for the creation of a fully contiguous and immersive cultural destination experience. The soon-to-be-launched initiative, The Africatown International Design Idea Competition, aims to work with the National Park Service Africatown Connection Blueways Program19Learn more. to do just that.

The National Park Service: The Africatown Connections Blueway

For the past several years, the Africatown community has been meeting with Liz Smith-Incer of the National Park Service to develop planning criteria for 15 sites of interest that tell the Africatown story along the Mobile waterways.

By establishing the Africatown Connections Blueway, descendants of Africatown’s original founders seek to reconnect their community to the surrounding waterways from which they have been separated. Of primary importance is to preserve and make available the international historical significance of Africatown to communities across Alabama, the United States, and the entire world, in the hopes of healing the sadness that stems from long-lost ties to Africa.

The Africatown International Design Idea Competition has included Blueway planning criteria in the competitions’s design programming for these sites, so that three-dimensional cultural landscapes can be envisioned along the Blueway, such as pavilions or water-edged tourism facilities that can help with interpretation of the waterway stories that are part of the history of enslavement.

The Next Step | A Multi-Site Design Challenge to Connect Public Spaces: The Africatown International Design Idea Competition

In 2018, M.O.V.E. Gulf Coast Community Development Corporation, a local nonprofit that works to lay the foundations for economic growth in underserved communities, set out to leverage the Clotilda discovery in ways that could economically benefit Africatown. M.O.V.E. Gulf Coast CDC contracted studiorotan to weave together Africatown’s many community plans and proposals into one comprehensive design framework, with the goal of ensuring an innovative user experience for the visitor and guaranteeing direct economic benefits to the community.

The competition invites multidisciplinary, international teams of architects, historians, artists, and students to design a series of African-centric monuments, memorials, and interpretive sites along a ten-mile cultural heritage experience called The Africatown Cultural Mile. Collectively, these venues speak to African architecture, design, pattern language, and cultural identity in ways that honor African ancestral history in America. The competition deliberately leverages the Clotilda discovery to constitute a new community revitalization program with a world-class heritage destination twist. It will be launched June 19, 2021, to students in 140 schools of architecture and to architecture professionals in America, Africa, and worldwide.

While much emphasis has been placed on the linked histories of Africatown and the Clotilda, the design competition leans heavily on the United Nations’ concept of “futures literacy,”20Learn more about UNESCO’s Futures Literacy initiative. which means:

- the future does not yet exist, BUT it can be imagined, and

- only humans have the ability to imagine.

It seeks to take advantage of our human ability to imagine a better future for Black people without constraints of racial oppression. In this way, it is also informed by Mark Dery’s idea of “Afrofuturism,” which envisions Black thought leaders in art, music, and literature using Black culture of the past with visions of the future to dream of a world without white supremacist thought, where people of African descent can display the vast range of human experiences, especially through the use of technology.21Learn more.

The competition uses the 2016 Africatown Neighborhood Plan, itself a brilliant and “futures-literate” foundational document, as a starting point. It rallies residents to actually imagine their future, by design, with a fresh catalogue of three-dimensional ideas from architects, designers, and students. These ideas will drive collective expectations and expand the ability to invest and transform Africatown into a new kind of model for community regeneration, meaning, the ability of communities that have suffered from economic, social, and environmental decline to rebuild themselves, because they see themselves having the power to do so. The competition therefore promotes a design approach to community development so that residents and supporters can better understand the role that their own imagination plays in developing the future of their own community, like the Clotilda Africans did.

The competition has full support from the Africatown community22Learn more. and seed sponsorship from the American Institute of Architects (AIA), the National Organization of Minority Architects (NOMA), Michael C. & Patsy B. Down Charitable Fund, Visit Mobile, the City of Prichard, and the 400 Years of African-American History Commission. We are ready to explore the richness of the African cultural landscape in all of its many dimensions.

Beyond Boundaries | The Africatown Cultural Mile

The Africatown International Design Idea Competition goes beyond Africatown’s Historic District boundaries to include four sites and sixteen venues that connect three regional cities and two continents. Competition boundaries expand to include ten miles of land routes and waterways, from Historic Africatown in Mobile through the Africatown Connections Blueway via Chickasaw and onto the proposed Africatown USA State Park in Prichard. The outcome is The Africatown Cultural Mile, a system of new and iconic public spaces that will serve tourists as well as current and future residents.

Africatown Cultural Mile: a land-based, water-based series of 16 memorials, monuments, and interpretive competition sites. Image courtesy of Renee Kemp-Rotan

The Cultural Mile idea also builds on decades of international discussion between Africatown descendants and delegations from Benin. These exchanges began in 1983, when John Smith, the mayor of the neighboring city of Prichard, formed a sister city relationship with Benin’s port city Quidah. Formal relations increased after Benin President Mathieu Kerekou in 1999 “stunned an all-black Baltimore church congregation by falling to his knees and begging forgiveness for the ‘shameful’ and ‘abominable’ role that [the Dahomean kings of his country] played in the slave trade,” as The New York Times wrote.23See source. He told the congregation, “Benin, my country, was the most important place for slave trade . . . We are the ones—our ancestors were the ones who sold out your ancestors to the white people, and the white people bought your ancestors and got them into various countries that they sent them just to build their economies, in the plantation, in the factories, farms, just like in America here.”24Sehu Shani, Hatred for Black People (Bloomington: Xlibris, 2013), 235.

In the years since, Kerekou and other Benin presidents have sent representatives to Africatown because of Benin’s historical participation in the Clotilda kidnappings. Africatown leaders have invited officials and private business owners to festivals and conferences to spark dialogue on cross-cultural ties, potential reparations, international trade, and Pan-African tourism. Thus, the Africatown story crosses two continents, Africa and America. It is a multisite, multilingual, and multicultural story.25Africatown, Alabama, recently received the international designation of a Site of Memory as one of 51 other documented Middle Passages along the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts associated with the UNESCO Slave Route Project.

Currently there is no comprehensive cultural tourism plan with design and performance standards tied to issues of African American slave history, cultural identity, architecture, and multi-site destination planning for this region. The competition and its cultural mile serve as such.

This Africatown experience is too important to piecemeal or leave to chance.

National Africatown Roundtable and Public Space

There must be rigorous conversation about slavery between the Cities of Mobile and Prichard, the State of Alabama, and the residents of Africatown. This moment provides an opportunity for new education and action in and about restorative justice—first and foremost, for the descendants of the founders. Therefore, activist organizations organized by the Africatown Heritage Preservation Foundation propose that a National Africatown Roundtable be convened to establish an official history and interpretive narrative, along with design and development criteria. This process must be held to rigorous international standards and rise above local politics.

The Africatown story is an international one. Decisions about the local narrative and what the buildings and landscapes that house or interpret this history will look like must be made in collaboration with the descendant community and with other local, regional, and international stakeholders. That is why descendants are now demanding that they, along with a proposed Africatown Review Board of subject matter experts on African cultural landscapes,26The board consists of anthropologist Michael Blakey, planner (and report editor) Renee Kemp-Rotan, and architect Jack Travis. be included on all issues of slavery interpretation, cultural archaeology, architecture, design, preservation, and creative placemaking. This interpretive work should be carried out as outlined by the National Trust’s Engaging Descendant Communities in the Interpretation of Slavery at Museum and Historic Sites: A Rubric of Best Practices Established by the National Summit on Teaching Slavery. In fact, the rubric should be adopted as the community’s secular bible.27Learn more about engagement with descendant communities.

The Africatown community is excited to be part of the Dora Franklin Finley African-American Heritage Trail. The trail’s primary objective is to share Mobile’s multicultural legacy through increasing awareness of the following:

- the early Creoles de Color community,

- the African survivors from the Clotilda,

- the newly freed blacks who worshipped and built some of the oldest churches in Alabama,

- African Americans who settled in an area named, ironically, for Jefferson Davis (Davis Avenue, and later renamed Dr. Martin Luther King Ave), and

- the Civil Rights advocates integral to the desegregation of the city’s schools, workforce, and public offices.

“In the words of our late founder, ‘You can’t know where you’re going if you don’t know where you’ve been.’” —Karlos Finley, president, Dora Franklin Finley African-American Heritage Trail28See source.

Africatown’s Public Space Gaps: Truth & Reconciliation | A Crucial Step Toward a Better Future

Other steps towards the design of equitable public spaces in Africatown would include:

- Designing a public space in Africatown, such as the new Africatown Welcome Center (using community engagement processes, such as the rubric), where national truth and reconciliation fora on slavery can be held. Many slave descendant communities throughout America look forward to the day and public places, when and where this can occur. Many see the design of such places as the first step to the psychological and spiritual healing that is needed to accurately interpret America’s slave history for the public.

- Developing and implementing an Africatown Economic Development Plan around all public interpretive sites with market analysis, feasibility, and revenue studies, following the spirited recommendations of the 2016 Africatown Neighborhood Plan.

- Conducting a series of archaeological reviews, as required by the National Trust for Preservation Act of 1966, Section 106, in addition to issuing environmental impact statements for all public sites associated with Africatown’s history, especially culture sites in the Historic District.

- Applying for an Historic District Boundary Extension so that the existing Africatown Historic District boundaries could expand to include Lewis Quarters.

- Creating a Brownfield Update Committee to track the cleanup of all 22 EPA brownfields study sites, mostly public, along the proposed Africatown Cultural Mile.

- Forming local, county, and state government public–private partnerships that provide proportionate financial support for the production of equitable public space, and that also support logical ways of getting there.

As we rush towards our greatness with all deliberate speed, we pledge not to hasten towards any mediocre plans.

When the lions tell their story, the hunters will cease to be heroes. —African proverb

Biographies

is an architect, author, academic, and activist. He currently serves on the faculty at the University of Michigan Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning. A 2017 Smithsonian Cooper-Hewitt Design Museum National Design Award winner, his creative practice specializes in engaging communities in collaborative and participatory design processes. He’s particularly interested in the production of various forms of space, and in understanding how publically accessible and responsive design can radically transform the trajectory of lives and environments, especially for those on the margins of society. A leading scholar of African Americans in the field of architecture, his books, essays, articles, and public talks explore the rich social, cultural, political, historical, and aesthetic contributions of oft-ignored practitioners of color. The former director of the Detroit Community Design Center, Wilkins is the author of The Aesthetics of Equity: Notes on Race, Space, Architecture & Music, Ruffneck Constructivist, and Diversity Among Architects: From Margin to Center as well as co-editor of Activist Architecture: A Field Guide to Community-Based Practice.

(Associate AIA/NOMA) is an urban designer, master planner, and the CEO of studiorotan, a cultural heritage/civic design firm. She is the first African American woman to graduate from Syracuse University with a bachelor’s degree in architecture. She attended London’s Architectural Association and graduated from Columbia University with a master’s in urban and regional planning. She is presently the professional competition advisor for The Africatown International Design Idea Competition. Read more.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.