Africatown, Alabama

Sites of Interpretation | The Africatown International Design Idea Competition

Our world faces complex challenges that threaten all aspects of Black space and the disenfranchised lives contained within it. We must elevate discussions about the interpretation of Black history and Black space in ways that protect the truth, health, safety, and welfare of Africatown, Alabama—in the Deep South.

In 2018, against the backdrop of the Clotilda discovery,1Learn more about the Clotilda, Africatown, and this community’s history. M.O.V.E. Gulf Coast Community Development Corporation (led by this report’s associate editor, Vickii Howell) commissioned my practice, studiorotan, to explore a range of planning tools that could unite divergent Africatown community interests under one single big idea.

The Africatown International Design Idea Competition was developed to prove how historic, yet underserved, communities such as Africatown can harness the power of design to contribute creative (rather than mundane) solutions to multisite and multiscale development issues in the service of an authentic narrative.

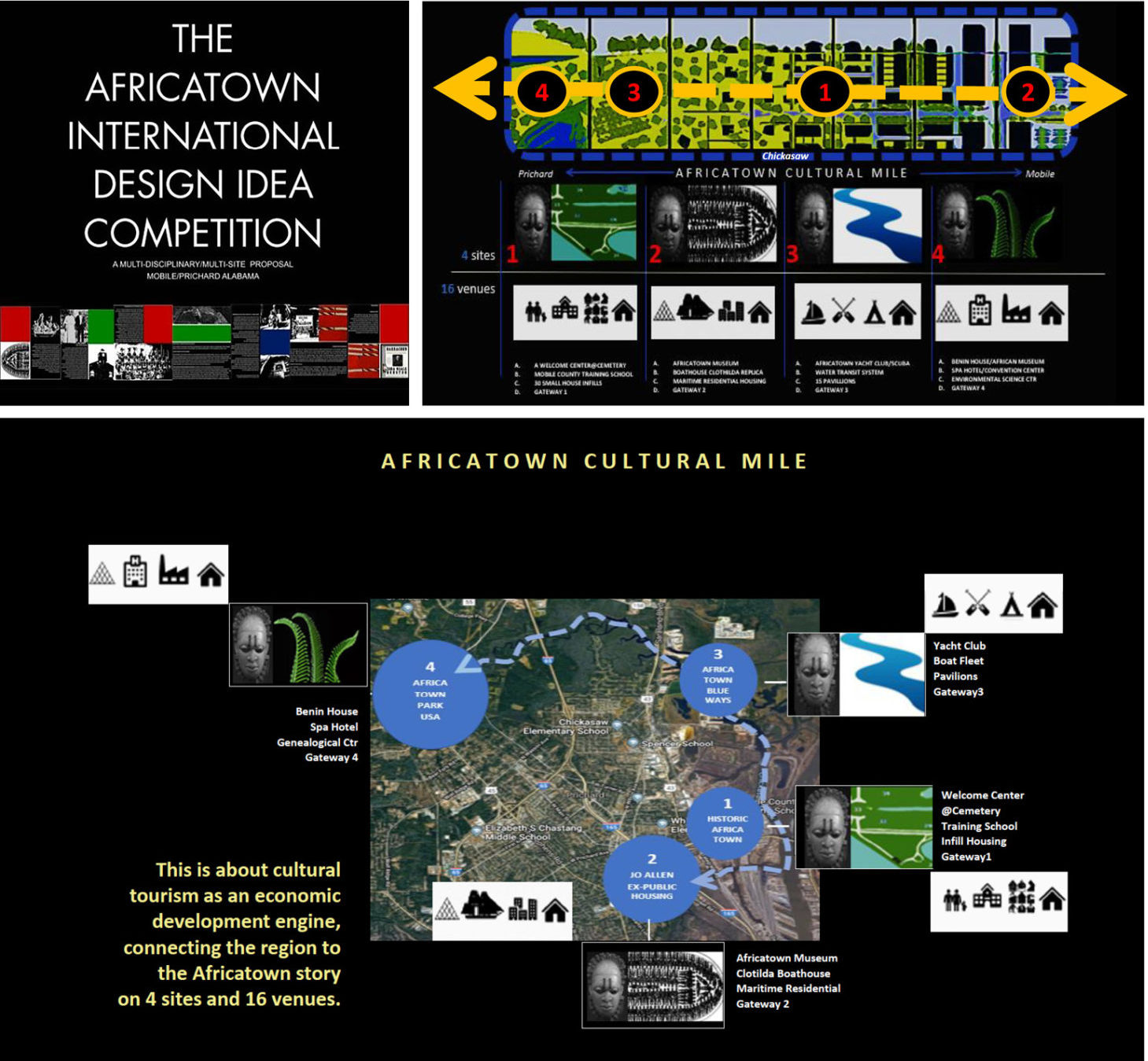

During the competition development phase, many community engagement events led to the identification of many site priorities, which, in turn, led to a well-defined matrix of multiple Black spaces—monuments, memorials, and interpretive sites that together tell the stories and produce what the competition now calls The Africatown Cultural Mile.2Learn more about planning efforts and the ways in which this competition fits into larger community initiatives and organizing. The story is bigger than Africatown’s historic district.

After listening to and consulting with the community, we dedicated the competition to committing all historic points of interest to the regeneration of Africatown.3Learn more. Through design programming, we constructed multivocal narratives at multiple sites to arrive at fresh interpretations of Black resilience in Black spaces throughout Mobile.

Here, we use design as a tool for spatial justice—to raise public awareness, promote imagination, repair community inequities, and secure economic benefits—by insisting that design ideas transform this unique African American story into a world-class cultural heritage destination.

Additional details about the Africatown design challenge can be found through the following tour of interpretive sites.

Africatown International Design Idea Competition program book cover and Africatown Cultural Mile concept maps. Images courtesy of Renee Kemp-Rotan

The competition is organized around four sites, each with four venues for interpretation or community development. Each site also hosts one of four “memorial gateways” that seek to honor the Africatown story.

Africatown Cemetery

Built by the founders in the nineteenth century, the Africatown cemetery holds the graves of many who arrived on the Clotilda, including Cudjo Lewis. This unkempt site, located on a hill, has been partially excavated by members of the archaeology department at the College of William and Mary, in 2010.

Contamination is a concern at this property. In the era when the founders were interred, arsenic was used for embalming; flooding and erosion could cause leaching. Former industrial sites adjacent to the cemetery may also harbor pollutants.

The competition stipulates that care must be given to the preservation of this historic cemetery, which will serve as the first memorial gateway. Adjacent to the cemetery will be the new Africatown Welcome Center.

The Africatown Welcome Center (competition venue 1, site 1)

The old Welcome Center was a doublewide trailer located on 2.8 acres of donated land across from the Africatown Cemetery; it was blown down by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. What’s left was vandalized in 2011, as evidenced by the broken busts of Prichard Mayor John Smith and Cudjo Lewis, which had been donated by filmmakers Thomas Akodjinou of Benin and Felix Eklu of Togo.

The new Welcome Center, partially funded by money from the 2010 BP Gulf Coast oil spill settlement, is to be built in the next few years on the old Welcome Center site. Successful design precedents near similar African burial grounds include New York City’s African Burial Ground National Monument and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. Interpretation of these sacred sites should be guided by Engaging Descendant Communities in the Interpretation of Slavery at Museums and Historic Sites: A Rubric of Best Practices Established by the National Summit on Teaching Slavery.4Learn more about the rubric

Graveyard Alley

Descendants remain deeply concerned about potential unmarked gravesites located in Graveyard Alley, a street that borders both the historic cemetery and the proposed new Welcome Center site. A cursory survey commissioned by the City of Mobile “found no gravesites—found no objects . . . ” along this street. But, the community was not convinced. They believed the site should be thoroughly examined by leading archeologists. Additionally, an archeological survey of the property and a cultural analysis of its history are required, according to guidelines set by the National Historic Preservation Act.

In January, 2021, the City of Mobile responded to these concerns and initiated an archaeological study of the site, authorizing a contract with the University of Southern Alabama (USA). Led by Jennifer Greene, the City’s project manager for the new Welcome Center, this exploratory team includes: Justin Dunnavant of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture’s Slave Wrecks Project; and USA faculty, including Kern Jackson, director of its African American studies program, and archaeologist Philip J. Carr, professor of anthropology and director of the Center for Archaeological Studies. The work includes a geophysical survey of subsurface land and an oral history project of property use before the 1940s. The initial search for unmarked graves along Graveyard Alley lasted 120 days. Thus far, no evidence of unmarked graves has been found that could impede construction of the Welcome Center.5Learn more.

The Africatown Heritage House

Africatown community leaders and activists have long insisted that artifacts from the Clotilda should be exhibited in new facilities in Africatown proper, as opposed to in the existing GulfQuest museum in downtown Mobile. Six hundred thousand dollars in public funds have already been earmarked for a temporary museum, the Heritage House, to be built next to the Hope Community Center, in Africatown. Current community debates focus on the design of this “heritage” structure and the degree to which it should reflect Afrocentric design principles. The community further hopes that the new Heritage House building might serve as a community meeting place and as the future office of the newly formed nonprofit Africatown Heritage Preservation Foundation, once a larger, more comprehensive museum in Africatown is built.

Union Church

Organized by the emancipated Clotilda Africans in late 1869, the Old Landmark Baptist Church is also the site of Africatown’s first school. It features the Clotilda Plaque of African and Yoruba Names, where Africatown’s founders listed their original names, remembering and honoring where they came from. A site of great importance, it is on The Dora Franklin Finley African American Heritage Trail.

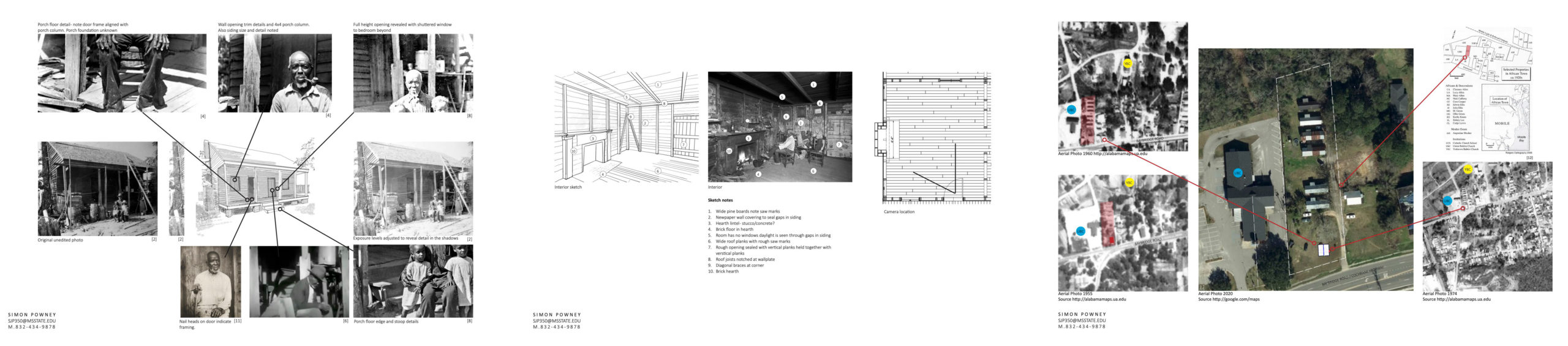

The Cudjo Lewis House Blueprint Initiative

The Alabama Historical Commission recently awarded a $14,000 grant to local nonprofit Africatown~CHESS to commission studiorotan to research and develop blueprints to (some day) rebuild the Cudjo Lewis House as a small house museum. As the Clotilda’s last known survivor, Kossola (Cudjo’s African name) shared his life’s experiences with writer and anthropologist, Zora Neale Hurston. Notes from her interviews are captured in Barracoon, her seminal work about chattel slavery and freedom—and Cudjo’s early life in Africa. Studiorotan and its team have used Hurstons’ photographs and interviews to generate these blueprints. This research, soon to be published as a book, is further supplemented by historical documents and descendant memories of Cudjo and architectural construction in nineteenth century Africatown.

Left: Diving with a Purpose scuba training. Credit: Vickii Howell. Center: Joycelyn Davis, cofounder of the Clotilda Descendants Association and the Spirit of the Ancestors Festival. Credit: Associated Press. Left: Community artifacts at the Whippet’s Den auxiliary space at MCTS. Credits: Vickii Howell

Mobile County Training School (MCTS) Expansion at Old Rosenwald Site (competition venue 2, site 1)

In 1912, Alabama was the birthplace of a program that created over 5,300 schools to serve freed African American families in states across the Deep South. Legendary educator Booker T. Washington with Tuskegee Institute’s School of Architecture, partnered with philanthropist Julius Rosenwald, a part owner of Sears, Roebuck and Co., to build local schools for emancipated Blacks. Today the Rosenwald School Fund is recognized as the single most important program that furthered African American education in the United States. Alabama had 407 Rosenwald Schools; scholars do not know how many are still standing. The Mobile County Training School, founded through this program, remains an important center for middle school education in Africatown. The competition requires an expansion of the school into a magnet school on world and African history.

The Mobile County Training School (MCTS) Alumni Association recently raised $25,000 in donations to upgrade and beautify the memorial courtyard at the school thanks to the leadership of its president, Anderson Flen. The courtyard once held the bell from the Clotilda; a replica now stands in its place. Funds also have been used to procure and install an electronic message board for community announcements. The school has hosted training sessions for youth scuba with Black Scuba Association and Diving with a Purpose, designed to train MCTS students to work as underwater archaeologists at the Clotilda site. It has also hosted the annual Spirit of the Ancestors Festival, organized by Joycelyn Davis, cofounder of the Clotilda Descendants Association. The MCTS’s Auxiliary Space, called the Den, holds many community meetings and family artifacts, and the school’s courtyard hosts important events like The Middle Passage Ceremonies, Port Markers Event, and the Day of 1619 Healing, an occasion that included nationwide bell-ringing ceremonies to commemorate the four-hundredth anniversary of the first African slaves brought to Virginia.

The Mobile County Training School is the backbone of this community. Clotilda descendants started it. It is incumbent upon us to protect the education of our children for generations to come. Nothing less than excellence will do. Read the MCTS newsletter. We the Alumni remain committed. —Anderson Flen, president, MCTS Alumni Association, cofounder, Africatown Heritage Preservation Foundation

Infill Housing on Tax Delinquent or Vacant Sites within Africatown (competition venue 3, site 1)

Competition entrants are asked to design front elevations for thirty units of infill housing that pay homage to African design aesthetics while preserving historic architectural principles within the Africatown Historic District. Over a third of Africatown’s land is currently vacant.6Learn more about Africatown’s land use.

Memorial Gateway One at the Historic Africatown Cemetery (competition venue 4, site 1)

Site Two: Josephine Allen Public Housing | Future Clotilda Museum Boathouse

Josephine Allen Public Housing Complex

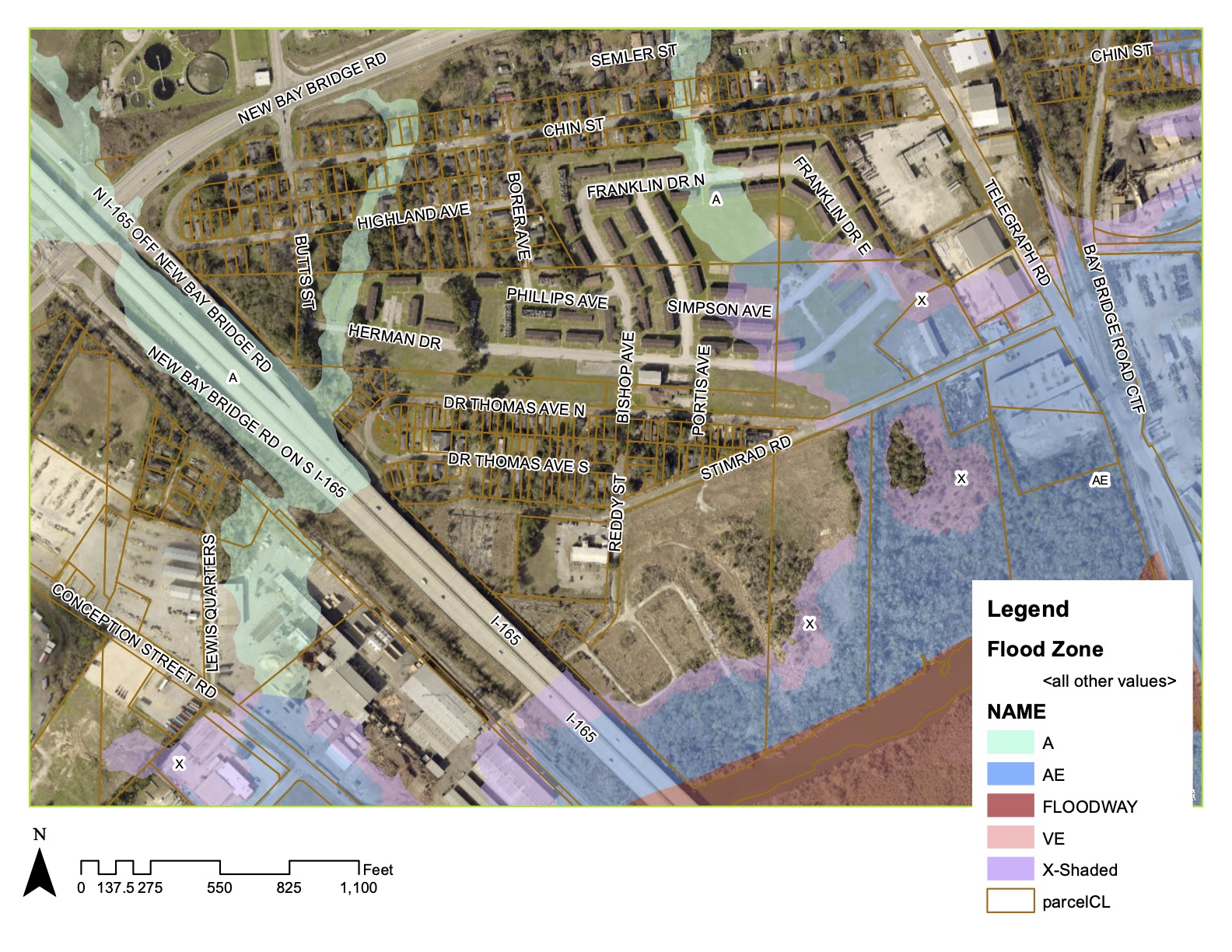

Due to reductions in federal funds, low occupancy rates, extensive disrepair, and floodplain issues, the Mobile Housing Board voted to close the 292-unit Josephine Allen Public Housing Complex in 2011.

Structures on the 50-acre site are currently being demolished. The Mobile Housing Board received permission from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development to sell the property in 2015, though no buyers have been found.

Africatown Museum and Clotilda Boathouse (competition venues 1 and 2, site 2)

The competition imagines the former public housing site as the location for (1) a 50,000 square foot Africatown Museum with (2) a full-scale replica of the Clotilda, sitting in a “purpose-driven” floodplain, as in “let’s float the boat.”

A flood zone map of the Happy Hills neighborhood of Africatown and the former Josephine Allen Public Housing Complex. Map courtesy of Vickii Howell

Maritime Residential Housing (competition venue 3, site 2)

The competition proposes 300 units of new mixed income/mixed-use maritime-themed housing, replacing the housing lost from the demolition of Josephine Allen. This site is an Opportunity Zone. It is also part of a recent EPA Brownfield Grant and is adjacent to Three Mile Creek, an important interpretive water corridor along The Africatown Connections Blueway/Africatown Cultural Mile.

Memorial Gateway Two at the Place of Baptism (competition venue 4, site 2)

A proposed path from the Africatown Museum and Clotilda Boathouse will go to the water’s edge, the Place of Baptism, where sacred community commemorative rituals are held. Plans are for water taxis to take tourists to the Clotilda discovery site (memorial gateway three).

The boat is what created us, so the boat, again, can redefine us. —Cleon Jones, longtime resident and president, Africatown Community Development Corporation7“In Africatown, the found ship Clotilda ignites hope, validates heritage,” AL.com. See source.

Site Three: Africatown Connections Blueway and The Africatown Cultural Mile

Africatown Connections Blueway

The Africatown Connections Blueway was initiated by the community, with technical assistance from the National Park Service Rivers, Trails, and Conservation Assistance program. The Blueway’s mission is to “preserve the history, natural spaces, habitat, and waterways of historical Africatown.” Five years of planning charrettes have sought to channel residents’ desire for water-edged interpretive trails that narrate the Africatown story through educational hikes, bike rides, trails, water festivals, and paddle trips. The Blueway contains 14 proposed points of interest that go through the City of Chickasaw and stretch all the way to Africatown USA State Park in Prichard.

The Africatown Cultural Mile (competition venue 1, site 3)

The Africatown Cultural Mile, as imagined, is the competition’s proposal to design a series of immersive experiences programmed to connect and develop the Blueway into three-dimensional interpretive sites with buildings, memorials, public spaces, events, and pavilions.

Africatown Yacht & Scuba Club (competition venue 2, site 3)

Interpretive Pavilions and Water Taxi System (competition venue 3, site 3)

15 interpretive pavilions along the Africatown Connections Blueway will help tell the Africatown story to tourists. Connecting these Blueway interpretive pavilions is a proposed community-operated, African-branded water taxi transit system.

Memorial Gateway Three at the Clotilda Discovery Site (competition venue 4, site 3)

Site Four: Prichard | Africatown USA State Park

Africatown USA State Park

The 150-acre Africatown USA State Park is located in the neighboring city of Prichard. The park was proposed by a group of African American political leaders and legislators in the mid 1980s and established by the State of Alabama in 2012 to serve as a regional hub for the promotion of African culture and commerce. The park originally envisioned that representatives from 30 African countries would each design and develop five acres of land within the park to promote relationships with Africatown.

The Benin House (competition venue 1, site 4)

Since 1999, Benin has sent delegations to Africatown, officially seeking forgiveness for the role that the Kingdom of Dahomey—a former state whose boundaries are now within the Republic of Benin—played in the transtlantic slave trade by selling its war captives to Americans and Europeans as slaves.8Learn more about the differences between African and American slavery and how race inflected American slavery. As recently as 2018, a Beninese ambassador, who described himself as a prince of Dahomey, tearfully expressed his remorse for his own ancestors’ involvement in the slave trade during a trip to the Clotilda wreckage site with reporter Ben Raines.9“‘Forgive us, because we sold them,’ says African ambassador on possible slave ship find,” AL.com. See source.

Benin has offered public apologies to the Clotilda descendants through reconciliation ceremonies, public prayer, libations, and offers of land in Benin as reparations. Recent delegations shared Benin’s plans for “Revealing Benin,” a tourist movement that includes the design and development of five history museums, exploring the history of African slave trade cities along Benin’s coast. Connecting to this initiative, the competition proposes an African history museum, to be known as The Benin House. Plans for The Benin House are currently being developed by the nongovernmental organization BUDAL-GIE of Benin and include a genealogical center and an institute of ethnic studies.

African Visual and Performing Arts Theaters, African Spa Hotel, and Convention Center (competition venue 2, site 4)

African Business Center (competition venue 3, site 4)

Drawing on the founding idea of the Africatown USA State Park, the competition plans for an African business center and travel bureau in a new free trade zone for Pan-African commerce.

Memorial Gateway Four at The Door of Return (competition venue 4, site 4)

On the Benin coast in Ouidah is a monument called “The Door of No Return.” It is a memorial to those who might never return: to the kidnapped and enslaved Africans, who were taken to the Americas.

A companion gateway is envisioned for Africatown USA State Park as part of a transcontinental dialogue about the transatlantic slave trade. This monument will serve as both a memorial and an invitation for African Americans to reconnect with their African roots.

The slave ship was a strange and potent combination of war machine, mobile prison, and factory … with a wide array of actors, merchants, plantation owners, bankers, and government officials. It was a vessel of terror—slavery was a particular kind of hell. —Marcus Rediker, author, The Slave Ship: A Human Story

More about The Africatown International Design Idea Competition

In the words of the competition organizers:

THE AFRICATOWN INTERNATIONAL DESIGN IDEA COMPETITION is not about a single site in Historic Africatown, rather it is an interdisciplinary, multi-site design competition that breaks boundaries to organize around a series of land-based and water-based locations that summon the design of monuments, memorials, and interpretive sites that together tell the depth and breadth of the Africatown story. This design challenge is organized into four Competition SITES or zones described as: (1) The Africatown Historic District, (2) The Josephine Allen Site, (3) The Africatown Connections Blueways, and (4) The Africatown USA State Park. Thus, making the Competition a far-sighted impulse that soon will use multi-site design solutions to define the more visionary placemaking event called The Africatown Cultural Mile.

THE AFRICATOWN CULTURAL MILE IS A “COMPETITION INVENTION.” It is a BIG Idea that uses design programming as a means to consolidate COMMUNITY thoughts and plans into a deeper, more unified Africatown narrative that includes a broad series of interpretive sites: including sacred public spaces, cultural landscapes, places of baptism, historic churches, praying grounds, signature schools, maritime housing, welcome centers, museums, boathouses, walking paths, water taxis, genealogy parks, healing hotels, African performance theaters, pan-African trade and tourism agencies with gateways and parks that together create an integrated live/work/tourist experience with memorable living descendant narratives for Africatown, the city, and the world.

THE AFRICATOWN INTERNATIONAL DESIGN IDEA COMPETITION WITH ITS AFRICATOWN CULTURAL MILE is a highly innovative physical, economic, and cultural design exploration that reshapes the perception of Africatown—from that of a singular and discrete historic district—into a regional geo-political narrative about social justice, American slavery, southern plantation economies, the Clotilda (last slave ship) Discovery, Africatown Founders and Clotilda Descendants. The objective of the Competition is to use “design as a tool of inquiry” that interprets Africatown’s history through the lens of world-class destination planning goals to uplift the economic vitality of the Africatown community, the city of Mobile, state of Alabama, this region, and the world.

Competition entrants may select from any of the four sites to design and may submit proposals for one to all four of the sites. Each proposal must include the design of all four venues associated with that site.

The Africatown International Design Idea Competition when launched Juneteenth 2021 will be one of the largest multisite, African-centric design challenges ever. The yearlong competition is open to architects, designers, planners, artists, and students from anywhere in the world. Winners will be announced Juneteenth 2022. The competition is funded, in part, by the American Institute of Architects, the National Organization of Minority Architects, as well as Visit Mobile, the Michael C. & Patsy B. Dow Charitable Fund, and the City of Prichard.

Best solutions will be decided by a design jury of 16 members. Eight jurors will come from the Africatown descendant community and the remaining eight will consist of architects, designers, historians, and archaeologists. Jack Travis, FAIA, architect, designer, and scholar of African-centric design principles is jury chair. Jurors will also serve as contributing editors to a two-volume book: The Africatown International Design Idea Competition, Volume 1: will give competitors insight into juror philosophies on African history, design, and community development. Volume 1 can be secured through the competition website at registration. The Africatown International Design Idea Competition, Volume 2 will be published following the end of the competition. Volume 2 will include all design submissions and will serve as a catalogue for the community to use in its regeneration of Africatown and the Africatown story.

Biographies

(Associate AIA/NOMA) is an urban designer, master planner, and the CEO of studiorotan, a cultural heritage/civic design firm. She is the first African American woman to graduate from Syracuse University with a bachelor’s degree in architecture. She attended London’s Architectural Association and graduated from Columbia University with a master’s in urban and regional planning. She is presently the professional competition advisor for The Africatown International Design Idea Competition. Read More.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.