Today, decades of industrial encroachment, coupled with a destructive history of decisions made by public and private interests regarding land use and infrastructure, threaten Africatown’s health and viability. In the feature below, Vickii Howell, president and CEO of M.O.V.E. Gulf Coast Community Development Corporation, describes the history of land use in Africatown, the ways in which this community has been exploited, ignored, and isolated, and how it is fighting back through planning and investment.

Africatown’s Union Missionary Baptist Church. Credit: Graveyardwalker (Amy Walker), CC BY-SA 4.0 (via Wikimedia Commons)

Pressing Infrastructural Needs

Emancipated Africans built Africatown’s first infrastructures on land they bought from their former enslaver, Timothy Meaher.1“From the Holds of the Clotilda to Africatown,” the UNESCO Courier, 2019. See source. On this land they built their own homes; founded a church and its cemetery; and organized a school for their children, first at Union Church and later in a new building made possible with assistance from philanthropist Julius Rosenwald of Sears, Roebuck and Co. and designed according to drawings made at the Tuskegee Institute.2The Tuskegee Institute School of Architecture produced drawings for more than 4,000 Rosenwald schools in the South.

Unlike these early community initiatives, later infrastructure improvements in Africatown such as the Bay Road Bridge have been built to serve the interests of commuters, industry, and corporations, not Africatown’s residents.

Today, Africatown’s most pressing infrastructure needs include:

- limiting the intrusion of industry into what is left of its diminished residential community,

- using excitement around the Clotilda3 Learn more about the Clotilda and the history of Africatown in the report’s introduction. discovery to preserve Africatown’s remaining residential areas and its institutional and historical facilities,

- revitalizing its tax-delinquent properties, and

- attracting new infrastructure investments (i.e., housing, schools, sidewalks, public transportation, retail, and well-designed interpretive sites) that secure Africatown’s future as a cultural heritage destination for tourists, and as a viable, thriving community for descendants and residents.

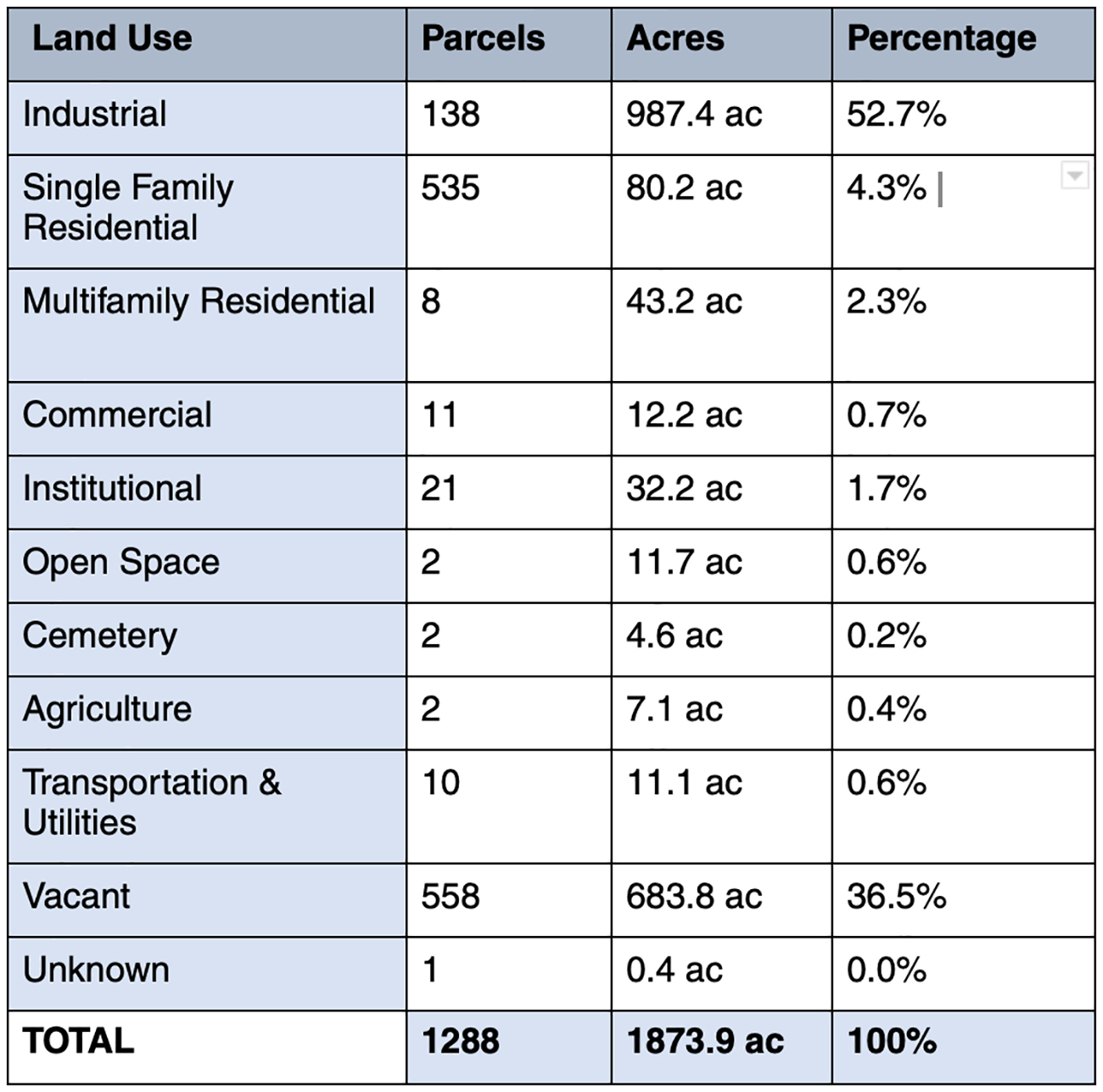

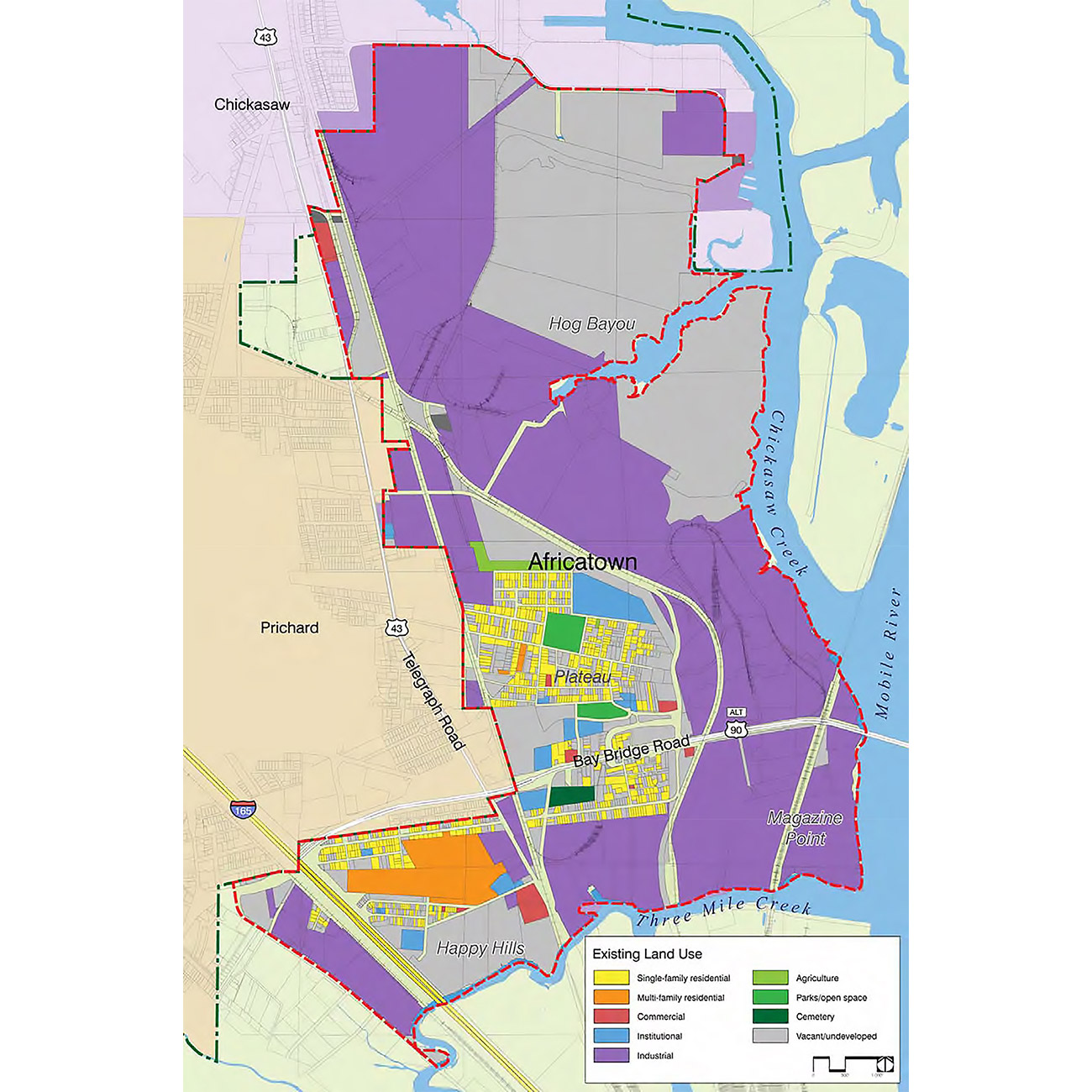

Along the Waterfront | All Heavy Industry

A map of current land use in Africatown. The historic core of Africatown is in the Plateau and Magazine Point neighborhoods, now surrounded by industry (purple) and hemmed in and bisected by highways and the Bay Bridge Road and Cochrane–Africatown USA Bridge. Further isolated and now separated by Interstate 165 is Lewis Quarters in the Happy Hills census tract (bottom left). Credit: Africatown Neighborhood Plan

The founders’ purchase of land was a remarkable act of autonomy and self-sufficiency that sustained a flourishing community for years. But the community never owned or controlled the immediately adjacent land, making it vulnerable to encroaching industry. This has placed the sovereignty of Africatown at the mercy of outside interests—including those of their former slave masters, the Meahers. Local tax records show that Meaher’s descendants still own upwards of 260 acres in and around Africatown, an estimated 14 percent of the community’s land. Signs with the name of their real estate holding company, Chippewa Lakes, dot the surroundings. Court filings indicate that the family’s real estate and timber holdings are worth an estimated $36 million.4“Finding the last ship known to have brought enslaved Africans to America and the descendants of its survivors,” 60 Minutes, CBS News. See source. See also: “America’s Cancerous Legacy for the Descendants of the Kidnapped Africans Who Arrived on the Last Slave Ship,” Daily Beast. See source.

Africatown’s location has long been a regional magnet for industry, given its position at the edge of Three Mile Creek and its proximity to the Alabama Port Authority (state docks) along the Mobile River. The community’s land has attracted railroad companies, mills, and other industrial uses.

The International Paper (IP) Company opened a plant in 1929 and operated for decades on land owned by Timothy Meaher’s son, Augustine. IP and Scott Paper Company expanded their footprints into the community in the mid-1940s, displacing residents who were primarily renters on non-descendant-owned land. Even owning land was no protection, as the homestead of Clotilda survivor Charlie Lewis was completely surrounded by Gulf Lumber Company.

Left: Street sign to the Lewis Quarters behind a lumber mill. Credit: Mike Kittrell for the Birmingham Times. Right: Lumber yard in front of Lewis Quarters. Credit: Vickii Howell

Two major rail lines serving these mills and factories criss-cross Africatown, with the Alabama and Gulf Coast Railway to the west and the CSX Railroad to the east.

Africatown residents voted to annex their unincorporated community into Mobile in 1960 in the hope of better public services, such as road paving and sewer lines. But soon after the annexation, the march toward industrialization accelerated. Around 1970, the City of Mobile began rezoning most of Africatown from residential to business/industrial use, turning the community into an industrial complex against the residents’ wishes.

Joe Womack, who grew up in Africatown and now heads the environmental justice group Africatown~C.H.E.S.S. (Clean, Healthy, Educated, Safe, Sustainable), wrote in a blog about how earlier generations of Africatown leaders had to fight hard to keep heavy industry out of their community:

After I returned to Mobile from college and a stint in the military, I found Henry Williams and others fighting for and defending Africatown against industrial takeover and the loss of land within the community. I would go to City Council meetings and watch as Henry Williams, Mrs. Arealia Craig, Tommy Ballard, and others would yell at Mobile’s City Council, letting them know how mad they were to have these issues come up over and over and over and over again.

One of the issues they defeated was an attempt by local businessmen to build a waste disposal facility for hazardous materials from around the world, including radioactive and toxic bio materials, in Hog Bayou. It would have been put in the area left vacant after International Paper was forced to leave Mobile because of pollution problems and a reduction in the paper mill business.5“Henry C. Williams, Father of Africatown History,” Africatown C.H.E.S.S website. See source.

In spite of their efforts, the current glut of industries located in and near Africatown demonstrates that although past community leaders won a few battles, they mostly lost, having neither control over the land nor the political power needed to stop the industrial takeover.

Roads and Bridges that Divide

Interstate and roadway decisions in Africatown have primarily served industries, not residents. Large, noisy transport trucks use the narrow Africatown Cutoff Road—cutting through the historic cemetery in an area called Graveyard Alley—to reach the Alabama State Docks. Other than the Bankhead Tunnel (circa 1941) under the Mobile River, Africatown’s central Bay Bridge Road is the only main thoroughfare to reach the more prosperous Eastern Shore across Mobile Bay.

State highway officials began widening Africatown’s Bay Bridge Road in the 1980s to accommodate more traffic, with the efforts ramping up after the completion of the Cochrane–Africatown USA Bridge in 1992.6State of Alabama Engineering Hall of Fame. See source. On the westward approach to the bridge, officials used eminent domain to take community land that erased huge swaths of rental housing, along with Africatown’s main business district. These highways and roads also effectively divided Plateau and Magazine Point, Africatown’s main neighborhoods.

Left: Cochrane–Africatown USA Bridge crossing the Mobile River. Credit: Vickii Howell. Right: Traffic on Bay Bridge Road. Credit: Mike Kittrell for the Birmingham Times.

Interstate 165 opened in 1985 to provide access from I-65 to downtown Mobile. Costing $240 million, the freeway accommodated heavy trucks headed to the State Docks with dangerous cargo that could not go through the Bankhead or George Wallace tunnels, in addition to commuter traffic to the Eastern Shore.7Interstate Guide.com. See source. The freeway further divided Africatown.

Recent plans to build a new Bayway toll road and bridge would have added 50,000 more cars and big trucks to the toll-free Bay Bridge Road—a road that Africatown residents already describe as dangerous with the existing level of industrial and commuter traffic. Alabama’s governor declared the highway project dead in August 2019; however, this was due primarily to stiff opposition from affluent Eastern Shore residents, not those of Africatown.8Tyler Fingert, “Cochrane Bridge Traffic Expected to More than Double by 2040 with New Toll Bridge,” FOX10 News, accessed August 29, 2020. See source.

Recently, however, the governor has signaled support for a new proposal offered by the Eastern Shore and Mobile Metropolitan Planning Organizations: a $725 million “truck-only” bridge that would levy a $10 to $15 toll on commercial trucks 46 feet or longer. The stated goal is to use a $125 million federal grant before it expires. But this project raises the same concerns as before—only this time, it would lead to even more big trucks barreling down the Bay Bridge Road in an effort to avoid the toll.9 “Mobile, Eastern Shore MPOs roll out I-10 ‘truck-only’ $10-15 toll bridge proposal,” Yellow Hammer News, accessed April 27, 2021. See source; “Truck drivers highly opposed to I-10 toll bridge proposal across the Mobile River,” CBS News 5, WKRG. Accessed April 27, 2021. See source; “A truck-only toll may revive I-10 bridge plans, but truckers will study proposal,” Alabama Daily News. Accessed April 27, 2021. See source.

Perhaps now would be a good time for Africatown leaders and their representatives to reach out to the new Biden administration, which is touting a $2 trillion infrastructure plan. Using some of these funds to help build a toll-free bridge could address congestion and safety concerns while also making the roadways safer for Africatown residents, local travelers, and future tourists, who will no doubt descend on the area as soon as cultural amenities become available, perhaps as early as this summer.

Though Africatown is crisscrossed by roads, bridges, and railroads, these transit byways serve to isolate the community rather than connect it to downtown Mobile.

The Fight for Community Preservation

Despite these challenges, Africatown leaders have fought tooth and nail for decades to defend their community from infrastructure projects that have led to land loss and industrial encroachment, and continue to do so.

In an article published on the website Narratively, Womack described a situation that hit close to home and heart. Community leaders gathered one day to talk about efforts to bring a trucking company line into Africatown. At the meeting, Womack learned that the company was asking the city to rezone the requested area from residential to commercial, which would force his mother out of her home. When he informed her of this plan, she said, “Don’t let them take away my home.” His reply: “Don’t worry, momma, they won’t take it.”10Reese Wells, “The Fighting Spirit of Africatown.” Narratively, accessed August 29, 2020.

From that point onward, the retired Marine major went from fighting for his country to fighting for the community where his family has lived for four generations. “And I am going to win,” he has said.

Industrial encroachment wasn’t limited to the land itself but to the very air, as Darron Patterson, president of the Clotilda Descendants Association, describes. “The smell wasn’t that bad, but the fallout (the pollutants spewed into the air from the mills) was worse. Washed clothes hung on the line would be ruined and would have to be washed again.”11Source: Transcript of notes from an interview with Darron Patterson by Vickii Howell, August 2020.

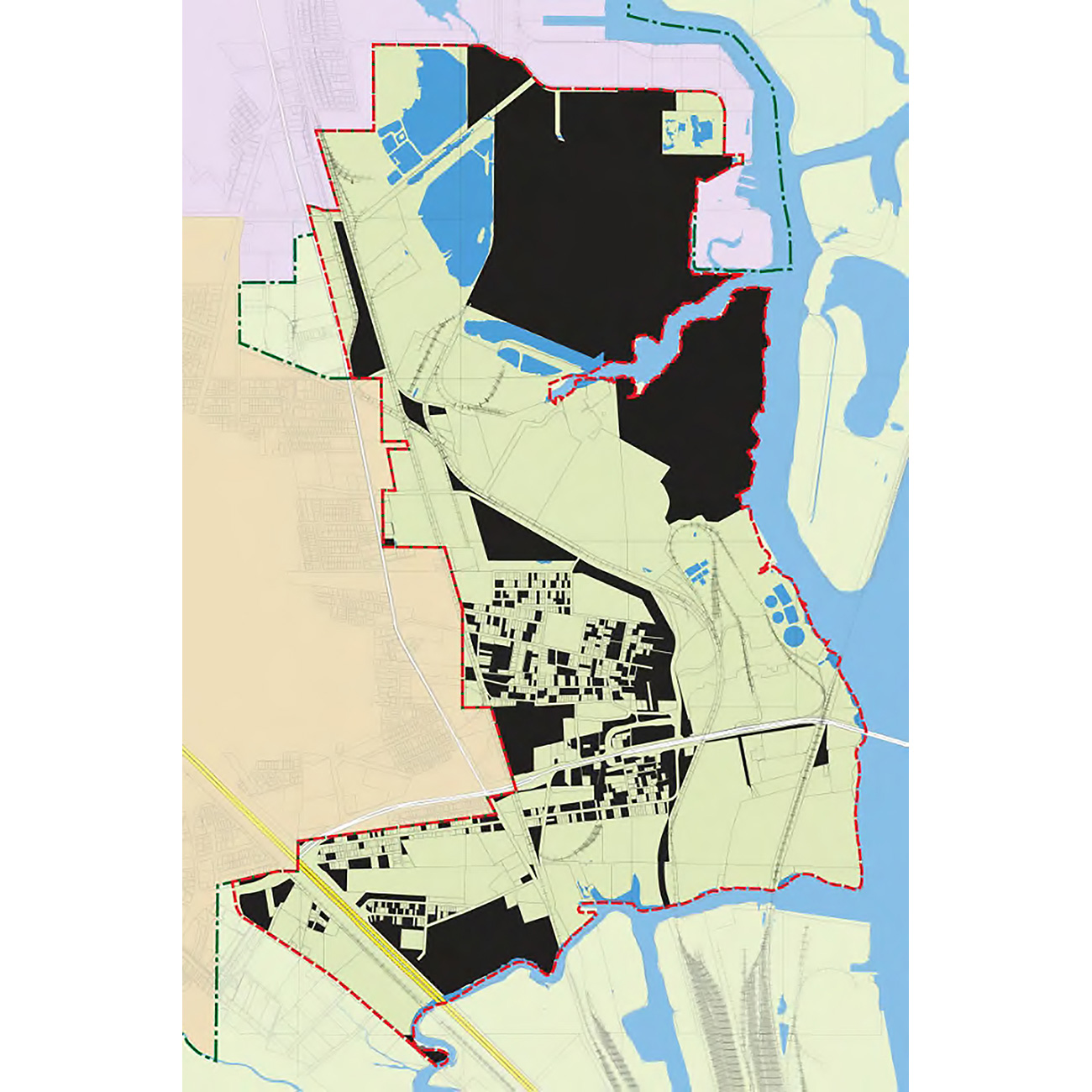

In black, vacant or tax-delinquent properties in Africatown in 2016. Credit: Africatown Neighborhood Plan

Africatown fell into further decline when International Paper closed in 2000, taking away thousands of direct and indirect employment opportunities. Today, only eight of the fourteen original Africatown neighborhoods are left.

Most of Africatown’s single-family detached homes are now in disrepair or tax delinquent; many of those that remain sit next to vacant lots. Because of its blighted conditions, Africatown was among the first areas targeted under Mobile’s Neighborhood Renewal Program (NRP). The city took inventory of the blight, but could not easily gain control of the properties, as identifying heirs and getting clear title to the dilapidated structures was virtually impossible.

To push past this problem, the NRP partnered with a data-driven initiative called the Innovation Team (I-Team), a program funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies that is based in the Mobile mayor’s office. The I-Team built a dashboard to identify and assess the condition of vacant and abandoned properties throughout the city. This “blight index” led officials to enact a state law allowing cities to use municipal liens rather than tax delinquency to claim ownership of a property if its owners were unreachable. In four years, Mobile has reduced the number of blighted homes by 45 percent.12Hana Schank, “Blight Is Eating American Cities. Here’s How Mobile, Alabama, Stopped It.” Fast Company, June 10, 2019. But while the program has made a significant difference across the city as a whole, in Africatown, blight remains a constant reminder of the community that used to be, and an impetus towards remediating the problem.

According to current city data available through an interactive map on the NRP website, more than 50 Africatown properties remain blighted, and about 175 are under a state or municipal lien for taxes or weeds. No group in Africatown has been explicitly charged with managing blighted, vacant, and tax delinquent properties for sale, renovation, or new construction. However, a recently proposed bill winding its way through the Alabama State Legislature would create an Africatown Redevelopment Corporation that could take on this role. The new nine-member corporation would be tasked with assembling land, issuing debts through bonds, and pursuing other activities to develop housing in the historic Africatown area. Community activists have some reservations about this initiative, however; in the proposed bill, just two of the corporation’s nine members would be appointed by the Africatown Heritage Preservation Foundation, along with one from the Clotilda Descendants Association.

Africatown’s most notable multifamily project, the 292-unit Mobile Housing Board–owned Josephine Allen public housing complex, was built upon the former home of the Pekin Cooperage Company, a large barrel manufacturer. The site’s former industrial use has raised concerns about the possible presence of petroleum-related products that will be assessed by the City’s EPA Brownfield grant.13RFQ, EPA BROWNFIELDS ASSESSMENT GRANT – AFRICATOWN PROJECT No. 2020-3005-09, City of Mobile, accessed September 9, 2020. Though the Mobile Housing Board closed the Allen housing project in 2011, its many dilapidated buildings remained a giant community eyesore until January 2020, when the City of Mobile finally set in motion the plan to demolish them. This 40-plus acre abandoned site in Magazine Point–Happy Hills is also located in a newly appointed Opportunity Zone, making it the most potentially profitable piece of government-controlled property in Africatown. New, progressive leadership could make plans to replace these demolished HUD-supported public housing units with new HUD-sanctioned mixed-income replacement housing to immediately end blight and enrich Africatown’s future with a development that could spur more community revitalization.

For years, Africatown leaders have struggled to transform their community. They knew its unique settlement history was the perfect vehicle to drive tourism. In 1997, the Africatown Community Mobilization Project sought a historic district designation to spur resurrection of the nineteenth-century town.14The Library of Congress, “AfricaTown, USA”, Local Legacies, accessed September 19, 2020. See source. “This is really just the break of the ice on what we consider a very unique history we need to tell,” argued former state representative William “Bill” Clark about how the historic designation could launch Africatown as a tourist destination.15John Sharp, “Pursuing historic recognition in Mobile’s Africatown,” Al.com, accessed August 2020. See source. But the drive faced significant pushback from industries with no appetite for potential development restrictions.

Nevertheless, resident determination resulted in some success. The Africatown Historic District was designated at the state level in 2009, defined roughly as bounded by Jakes Lane, Paper Mill, and Warren Roads and Chin and Railroad Streets. It is included as a stop on Mobile’s Dora Franklin Finley African American Heritage Trail. In 2012, the district was added to the National Register of Historic Places. However, the district boundaries do not include Lewis Quarters (where some of Clotilda African Charlie Lewis’ descendants still live) or most of Magazine Point on the other side of Bay Bridge Road. Despite these existing state and federal historic preservation designations, no revitalization via tourism has come to Africatown.

The Fight for Zoning and Site Control

Zoning remains a critical issue in Africatown, as vigilant local leaders scan Mobile city planning meeting agendas monthly, keeping a watchful eye on any changes that could potentially further erode their community’s remaining residential areas.

The City of Mobile is currently revamping its zoning regulations to ensure “the best quality development and living environment for the City and its citizens through fair and equitable administration of codes, ordinances, and plans,” according to Map for Mobile, the city’s comprehensive plan. The Mobile Environmental Justice Action Coalition, one of Africatown’s chief environmental advocacy organizations, scans all new zoning code proposals and consistently offers substantive counterproposals that reflect Africatown’s own recommendations for “highest and best” resident-friendly land use decisions.16 MEJAC, “The New City of Mobile Zoning Code: Kudos and Concerns.” MEJAC, March 8, 2019.

Recently, a community newcomer sought a variance to build a new home in Lewis Quarters. But her request to adjust the zoning to residential use revealed that what’s left of Clotilda African Charlie Lewis’ familial land is already zoned for heavy industry, as it is surrounded by a lumber yard and I-165.

Another recent attempt to adjust the zoning on a parcel of property designated for a farmer’s market failed after stiff opposition from some community leaders and Africatown supporters. Though some residents in the community fully supported the request because Africatown is a food desert, others feared that “spot-zoning” a site for commercial use could allow the parcel and those around it to one day be permanently rezoned commercial.17Joe Womack, “Africatown Residents Win over Commission to Block Zoning Variance,” Africatown C.H.E.S.S., September 25, 2020.

Neighborhood Planning and Future Revitalization

In 2015, the City of Mobile released the Africatown Neighborhood Plan request for proposals, asking for ideas to “set the direction for creating a 21st Century Africa Town [sic] neighborhood that is environmentally, socially, and economically sustainable,” and that respects “the historic nature of the area while striving to create a vibrant contemporary neighborhood.”

The resulting 2016 revitalization plan is designed to guide critical development improvements and infrastructure upgrades in alignment with residents’ stated desires. Through numerous planning workshops, engaged citizens authored recommendations for preserved homes and modernized housing plus business incubation centers focused on history and cultural tourism to attract visitors and new residents alike.

The plan does not seek to reinvent Africatown, but instead describes a consensus vision that takes advantage of the community’s unique assets. —The Africatown Neighborhood Plan (2016)

The plan says Africatown needs “critical mass” to jumpstart this process of leveraging the community’s assets. M.O.V.E. Gulf Coast Community Development Corporation and other community development organizations in Africatown believe that now is the time to move beyond planning to a more focused concentration on Africatown’s economic issues. We believe that the discovery of the Clotilda is this “critical event.” We also believe that The Africatown Cultural Mile (a proposed outcome of community visioning through M.O.V.E.’s new initiative, The Africatown International Design Idea Competition) could anchor this new “critical mass” as a tourism destination system, helping it become one of Alabama’s largest and most economically impactful cultural heritage tourist attractions. New roads, housing, power systems, and other infrastructure would need to be created to collectively support these new legacy assets in Africatown.

According to the Africatown Neighborhood Plan, “critical mass is difficult to quantify, but key components in achieving it are residential growth and physical improvements that have a high visual impact on those visiting or passing through the community.” Some of the plan’s many recommendations include:

- enhancing gateways into the historic community,

- demolishing severely dilapidated homes,

- acquiring vacant, blighted, and tax-delinquent properties,

- creating a land trust,

- developing housing, especially affordable homes, in strategic locations,

- reducing Africatown’s isolation from the rest of the city,

- encouraging improvements on industry properties, and

- developing a master plan for the Josephine Allen site.

These planning components, along with the Africatown Neighborhood Plan’s infrastructure proposals, will be included in The Africatown International Design Ideas Competition, and incorporated into the Africatown Cultural Mile.18Learn more about the Africatown International Ideas Competition.

Africatown’s Infrastructure Gap

Africatown needs public and private interests to engage with residents to support the following community-based infrastructure initiatives:

- the 2016 Africatown Neighborhood Plan recommendations,

- The Africatown Heritage Preservation Foundation in developing an Africatown Land Trust that includes control over tax-delinquent, vacant, and infill housing sites with community-based land use, site, and aesthetic control (similar to the Africatown Land Trust in Seattle, Washington),19Learn more in the feature The Racialization of Space and Spatialization of Race.

- City and State establishment of an annual Africatown capital projects budget with upgrades for housing, streets, sidewalks, parks, and public event spaces,

- mixed-income replacement housing at Josephine Allen Public Housing site,

- an anti-gentrification plan within the Africatown Historic District, and new architecture for infill housing, called an Africatown Village, perhaps using Williamsburg, Virginia, or American Village in Montevallo, Alabama, as models,

- community review of land use, zoning changes, variances, public housing authority unit replacement rules, and development applications for all opportunity zones,

- request for proposal development reviews to insist on diverse development teams and encourage African American developers to apply as a twenty-first century new wave of Africatown founders,

- a community benefits agreement for all design and development projects associated with design, development, and infrastructure improvements tied to the Africatown and Clotilda story, and

- implementation of the Africatown International Ideas Competition to secure world-class architectural concepts for proposed buildings and sites to support an extensive cultural heritage destination system worthy of Africatown’s unique history.

Biographies

is a journalist, writer, PR strategist, and socially conscious community builder. Upon returning home to Mobile in 2013, Howell joined the Mobile NAACP, becoming its executive director. She is currently the founder and president of M.O.V.E. (Making Opportunities Viable for Everyone) Gulf Coast Community Development Corporation, a nonprofit organization to build collaborative partnerships with businesses, governments, and other nonprofits to create a supportive economic development ecosystem that grows the businesses and socioeconomic capacity of entrepreneurs, workers, and families in historically underserved communities. Read more.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.