Universities are often charged with developing students’ professional skills to allow them to prosper in the future. However, many of these institutions fall short when it comes to supporting the current health needs of their specific student population. The physical, mental, and social health of students must be prioritized, with particular emphasis on challenges like housing, food, and financial insecurity that inhibit student success.

In this feature, Christie Poteet, director of the Office for Community and Civic Engagement at the University of North Carolina at Pembroke, and Deb Gunsallus, AmeriCorps VISTA for Hunger with the Office for Community and Civic Engagement at the University of North Carolina at Pembroke, describe how the CARE Resource Center operates on the University of North Carolina at Pembroke’s (UNCP) campus and serves the surrounding community. The center helps ensure students’ health and wellbeing beyond typical university standards by coordinating supportive housing, running a food pantry, and assisting with professional dress to allow students to land jobs. While the CARE Resource Center is working to serve and retain students from local counties such as Scotland and Robeson, it also stands as an example of how universities can begin going beyond the classroom to help their students succeed.—Morgan Augillard and Joey Swerdlin, Along the Lumbee River report editors

Christie Poteet and Deb Gunsallus outside of the CARE Resource Center at University of North Carolina at Pembroke. Credit: Andie Rea

The following has been excerpted from interviews conducted by the report editors.

The text has been edited for length and clarity.

Transforming the Office for Community and Civic Engagement

Christie Poteet (CP): I’ve been at UNCP for 12 years. I grew up in Appalachia and went to Berea College. It’s a work college where every student is on scholarship. You can’t pay to go to Berea, so everyone is low-income. The one thing everyone had in common was that we all knew what it meant to be a part of social programs. That college took care of me in a way that I knew other students were not being taken care of, because Berea College knew our life, they understood our backgrounds.

I felt like it was my mission in life to bring Berea College to other places in the world. After I left there, I got my master’s at UNC Greensboro, where I was introduced to how to incorporate service-learning into academic curricula. From there, I wanted to find a new job to serve students in a way that educated them about the ways that they can change the world through their own education.

Eventually, I found this job. Our office is responsible for engaging students in volunteer opportunities to be more active and engaged on campus and in the community. We work with several partners and 190-plus community-based organizations throughout the region to provide students with those opportunities, both through academic service learning and co-curricular service. When I started, we were engaging about 200 students in about 2,000 volunteer hours a year. Since then, we’ve grown to about 3,600 students and 34,000 hours, which is more than half our [student] population engaging in some type of service. It has become a culture of who we are: thinking about how we move the needle on these social problems that are plaguing our community, finding ways for students to find their passions, and putting them into action in ways that make sense for them and also create change in their communities. That’s the only way that we’re ever going to do anything different than what we’ve always done.

So that’s our primary mission, but in that, we recognize that our university was founded by and for American Indians in 1887 to serve our community because the minority population was not being recognized—they were being overlooked. This university was started to primarily focus on educating American Indian teachers, so it always had that focus of community, engaging community and meeting the community’s needs.

One of the main initiatives of our office is the CARE Resource Center, which includes an on-campus food pantry and professional clothing closet open to students, faculty, staff, and community members. Students are welcome to visit the pantry twice per month, while faculty and staff are welcome once per month. Community members who wish to receive food services are required to attend monthly educational workshops focused on life and career-development skills. Upon completion of each workshop, participants will be awarded a CARE Resource voucher to use at the pantry.

Feeding and Clothing the Community

CP: Before we started the food pantry in 2013, we collaborated with a service-learning course in sociology to survey our campus, with a goal of identifying the level of food insecurity at UNCP. Of the students they surveyed, 80 percent identified they were experiencing some level of food insecurity. That wasn’t surprising, because about 75 percent were Pell Grant-eligible, so we knew that we had a large number of students who were in need of food assistance. Students were having to make tough decisions between food and books or food and whatever other expense that financial aid didn’t cover.

We also were telling students that they needed to go on interviews, do job shadowing and internships, but they had nothing to wear. If you can’t afford food then you’re not concerned about a suit. So we incorporated the professional clothing closet into the center. Then a few years later we started introducing hygiene items, because we were thinking, “Okay, food, shampoo … What are the basic necessities that a student might need in order to be more successful here at UNCP?”

Over time, the food pantry system expanded and we connected to our local Walmart, where we go and pick up unsold food three times a week. In addition to that, Deb runs the other food recovery initiative, where we pick up from the Starbucks, Einstein Bros. Bagels, and another little cafe on campus. We’re doing food recovery on our own campus and in our community to repurpose good food that would go to waste and distribute it to our community.

We do have quite a bit of produce that comes in that comes in bad, though. One time, we were getting so many bananas; I mean hundreds and hundreds of pounds of bananas, and nobody can eat that many bananas. That’s how we connected to Noran [Sanford and GrowingChange]. We knew that he had the prison that he was trying to turn into something related to sustainable food development. I went there and saw his food composting, and I was like “Hey, let’s make this work.” Now any food that we get that we cannot give to students or the community, we compost it with Noran and other farmers to complete that cycle.

In Lumberton, we’re working with the Lumberton Housing Authority and a church community center. We also work with BART (Borderbelt AIDS Resource Team), who primarily focuses on clients who have HIV or AIDS and provides them with case management. They also have a food pantry. Whenever we are closed, we contact BART. They go to Walmart and pick up on our behalf so they can serve their clients better. Also, if we ever have excess food, we contact BART.

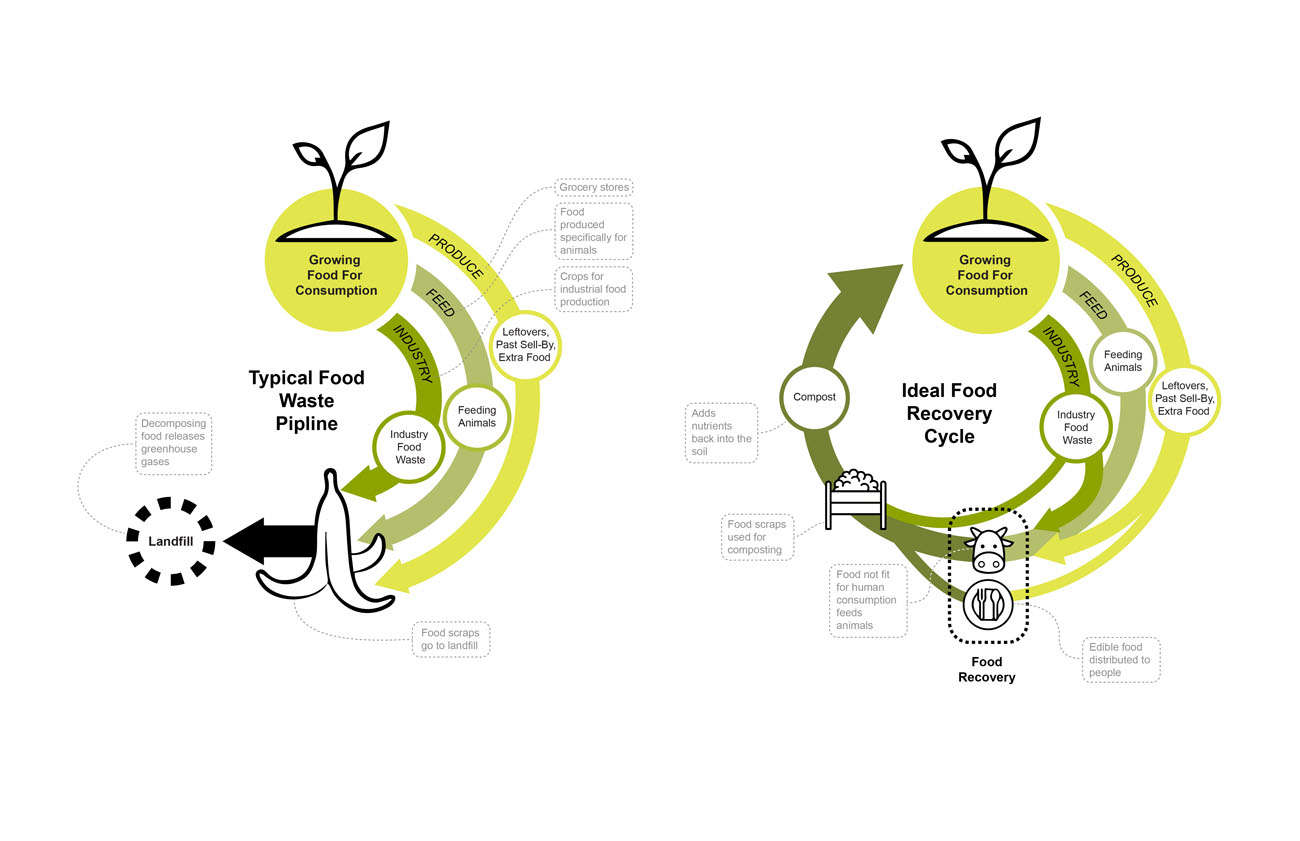

Deb has an interest in completing the food recovery hierarchy. [She asks,] “How do we make sure that the food cycle completes itself, so that we’re continuously recycling or reusing food in a way that helps us produce more food and educating that community on how to do that as well?”

The typical food waste pipeline versus the food recovery cycle, as described by Deb Gunsallus. Credit: Jonathon Brearley/Group Project

Deb Gunsallus (DG): For the CARE Resource Center, we focus on the food recovery hierarchy. We get recovered food from the primary location, which would be Walmart. The CARE Resource Center is a secondary location. We provide food for free, versus at Walmart where you have to pay for food. Next in line is feeding animals. We ask local farmers if they are feeding animals [and give them food that is not fit for human consumption, but can be safely eaten by animals]. Next under that is industrial waste, which we can’t really do anything with. Below that is composting, and lastly actually trashing it.

So composting is where Noran comes in, because he was not only feeding his chickens, but he was also using it to compost with flies and worms. It’s pretty interesting, actually.

We also reached out to our community. I talked to Bernice Oxendine, who has a little local farm about two streets down from our university, and he feeds his cows with this food waste. Then, he butchers his cows later on in the year, and then he gives that to his community also. So this is one way that we complete the cycle of the food recovery hierarchy.

Student-Led Community Workshops

CP: As we’ve grown over time, the CARE Center can’t address community needs the way we did before, because we just simply don’t have enough food. Since the mission of our office is really to educate and engage students in the community, we wanted to find a way to improve the quality of life for not only our students but for our community.

In 2018, we started Brave Foundations, a series of workshops offered to community members and run by students. We changed our policies so that in order for the community to access our services, they had to participate in educational workshops that were focused on career readiness, budgeting, healthy eating, and those types of things. We never wanted to get to that place where we had to put a caveat or a requirement on getting our food, but we simply could not keep up, and we weren’t moving the needle on food insecurity by just giving out food. We had to do more. This was also our way to engage students in opportunities to educate the public.

Student Service Leaders for adult life skills development lead these initiatives. We have outward-facing programs and inward-facing programs. Our outward-facing program finds ways for students to educate the community. We go into the high schools and middle schools to teach all of these different things. Then, we have inward-facing programming where we have students trying to recruit other students to run these workshops for the community. Student Service Leaders (like Deb, who just graduated in May) recruit other students, maybe through a service-learning class. Then, those students would come up with the topics for the adult life skills programming. We weren’t just saying that this is what we think you need: Instead, we asked, “What do you need from us and how can we assist?” We took that assessment of the community and developed the curriculum. Then, the student is responsible for recruiting volunteers to come in based on their area of expertise and deliver the curriculum.

One main issue we have in a rural community is transportation and access. In Pembroke, we try to find a location off campus to run our workshops because the community wasn’t being very responsive to a location on campus; getting to campus and parking on campus is an issue. We tried to find something downtown, but it’s still hard for people to get there. They always say that the number one issue is transportation. To counteract this, our plan is to move into other communities within our community and try to connect them with resources outside of the CARE Center. If they’re in Lumberton, which is 15 minutes up the road, we know that they can’t get to the CARE Center, so let’s connect them to church and community centers that are in that community. Then, we still go in and offer the workshops ourselves. We’re trying to recreate our model in other smaller communities so that other people don’t feel like they have to come to Pembroke to get services.

For example, last year Deb went to our local high schools and developed a workshop on how to educate high school juniors and seniors through a life skills program focused on how to eat healthy food that grows in your backyard. I would say her outreach is one of her strongest things that we’ve seen come out of the CARE Center in awhile.

DG: At first, we did just a counting calories activity, and the students didn’t really like that, to be honest. After that, they learned, “If this is so low in calories, how can I make it myself?” A plan for growing cucumbers and stuff takes time, though, and one thing that the younger generation lacks is patience. So with the garden, they’re just like, “I want it now. I want it now.” And it’s like, “No, you gotta wait for it.” And they’re asking, “Why do I gotta wait for it?” There are multiple things with food that you have to teach people; it’s not only what kind of soil or what kind of plant grows well in North Carolina, but also patience.

Emergency Housing

CP: Back in 2016, we also anecdotally knew that students were facing homelessness. We had heard stories that some students were living in cars, the gym, or sneaking into the library at night to sleep and then going to class. Again, we solicited the help of the service-learning course to do a survey to evaluate the level of homelessness on our campus. In that survey we found that about 10 percent of students said that at one time they considered dropping out of the university because they didn’t have a safe and secure way to live. That was only 6 percent during the academic school year, but during the summer months it reached 10 percent. We were able to take that data and work with the university to think about how we can address homelessness.

With these data in hand, we asked the university if we could use an empty campus building for emergency housing, and they flat-out said, “It’s a risk and liability to house students, and we can’t house students for free.” Which made sense to me. So we started looking at buildings that we could rent.

At the time, we had a community partner—the Burnt Swamp Baptist Association, who’s across the street from campus—who had a building that I knew was empty. Since we’re a state institution, our lawyer said, “That isn’t gonna happen.” In order for us to own or rent a building and put students there to live, the building would have to be up to state code, and we didn’t have the funding to upgrade the building.

We got a little creative with the help of university counsel and identified a partnership with Burnt Swamp Baptist Association where they maintain the building, but we would provide programming. The programs provide housing for students who are in need of emergency housing. Students can stay up to 6 weeks, and in that time they meet with our VISTA, Deb or whoever it is at that time. They work with them on trying to identify whatever their needs are: whether it’s a job, housing, or sometimes it’s a car to get to a job. Whatever it is, we try to work with them to identify needs and better connect them to community resources so they can transition to more stable and secure housing.

Future: Center for Engaged Learning

CP: The long-term plan for our office is to create a Center for Engaged Learning. In that space, my idea is that we will house all the initiatives that we’ve created: the CARE Resource Center, the Brave Foundations Program, and our service-learning programming. It’ll be a one-stop location where our community and our campus can interface: a space where students come in to find ways to engage and impact the community, and the community comes in to get services and improve their quality of life.

Right now, we’re kind of decentralized and scattered all over the place. I think if we created that central hub—that Center for Engaged Learning—we can better create this network of resources—along with GrowingChange, the churches and community centers, the Bernice Oxendines and offer more workshops to farmers about how they can better connect to entities like the universities.

Creating a New Standard

CP: Most of the institutions in the state have food pantries; that’s not new. The way that we connect to Walmart and all these other entities, and the way that we’re educating our community with students: I think that is unique to UNCP. We offer all types of food—meats, dairy, produce—I think that’s unique, too. The way we’re composting and connecting to local farmers is unique. Our homeless shelter is absolutely one of a kind. I know of three other university-affiliated shelters in the nation, and none of those are supported by a state institution. I think the way we operate our pantry as an educational facility, not just a place to get food, is pretty unique too. We’ve presented at national conferences about it. Our students present on it. I present on it. It’s just a pretty unique environment that I think we’ve created to address the needs of our students and support them.

It all stemmed from a poor girl from the mountains of Tennessee who needed to get an education and was blessed to go to Berea College, which taught her to care about the world in a different way. They supported me, and I knew our students needed that same support. I can’t ask them to go volunteer to feed someone in the community if they’re starving too. We push students to take what they learn and make a difference.

Over the last ten years, we’ve absolutely grown to where—I think society has changed, too—that’s part of who we are, it’s part of our values at the university. It wasn’t when I first got here. Our mission was to serve our community, but now it’s stated in our values that we are committed to service. We offer more service-learning courses per capita than any other school in the NC system, which is important, because we compete with Chapel Hill and all these big institutions, and we’re offering more. Service is an important part of who we are as an institution. Students come to expect it: “If my course isn’t service-learning, I want it to be. I wanna know how this matters. I want to know how a math class contributes to the world.”

I think over the years, we’ve absolutely changed the culture of how our students are thinking about their education and how it makes a difference. People always say you need a benchmark to understand what other universities are doing. In this world—I don’t mean to toot our own horn here—we are trailblazers. We are setting the standard.

Biographies

is the Director of the Office for Community and Civic Engagement at the University of North Carolina at Pembroke.

is an AmeriCorps VISTA for Hunger with the Office for Community and Civic Engagement at the University of North Carolina at Pembroke, where she is completing her Bachelor’s Degree in Criminal Justice.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.