The digital divide has long been an issue in Brownsville, but when COVID-19 arrived in the Valley, it became even more urgent, as schools and businesses shut down and people without good internet connection found themselves isolated, unable to learn or work. While we were working on this report, the City of Brownsville issued a request for proposals for a Broadband Feasibility and Digital Inclusion Plan, and we realized this was a perfect opportunity to explore a different, but no less important, kind of infrastructure than the transportation and drainage systems we discussed with the organization LUPE in an earlier feature. In the feature below, Jordana Barton, vice president of community investments at Methodist Healthcare Ministries and formerly of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, shares her research on the region’s digital divide. —Lizzie MacWillie, Kelsey Menzel, Jesse Miller, and Josué Ramirez, Brownsville Undercurrents editors

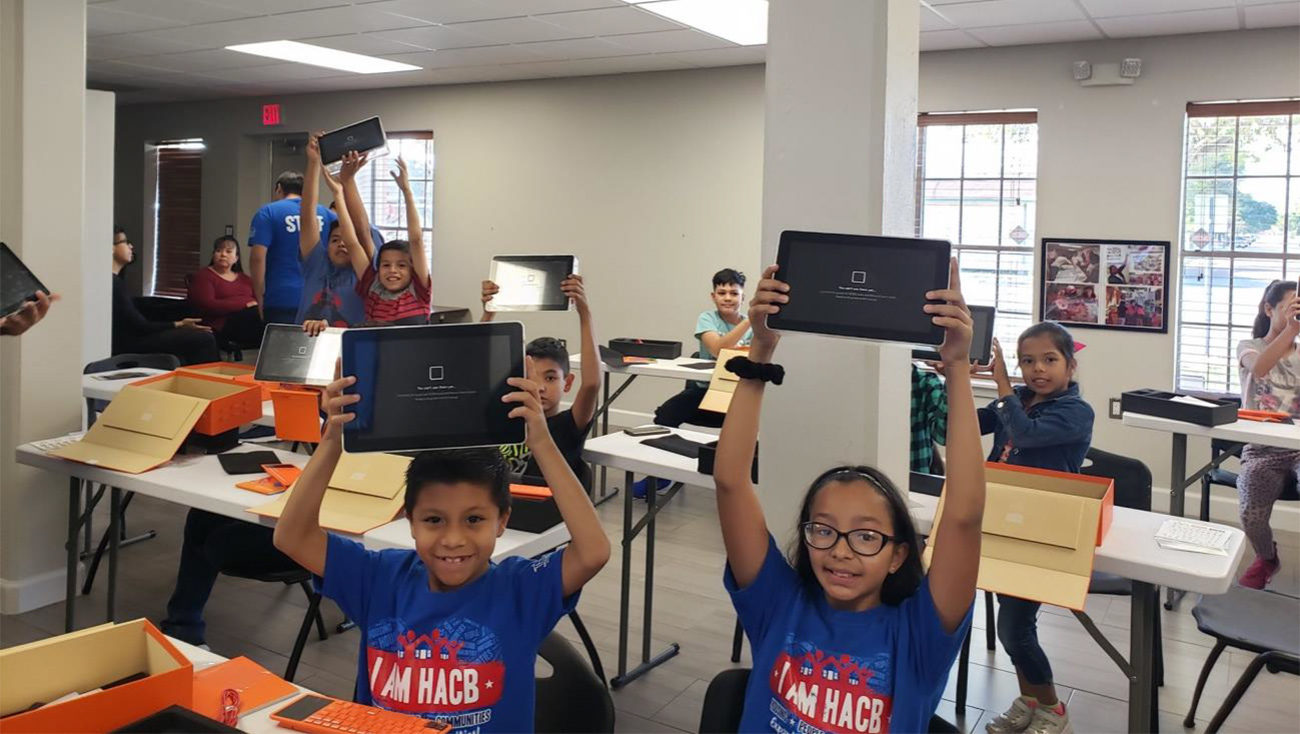

COVID-19 has presented challenges for families across the digital divide, as many lack internet connectivity and technology for remote learning. Photo courtesy of the Housing Authority of the City of Brownsville

Colonia residents of the border region were the first to call the attention of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas to the detrimental impact of the digital divide on economic opportunity.1Digital divide definition: The gap between people who have access to the internet and know how to use it and those who do not have such access or knowledge. Benton Institute for Broadband and Society, “The Next Generation Network Connectivity Handbook: A Guide for Community Leaders Seeking Affordable, Abundant Bandwidth,” by Blair Levin and Denise Linn, accessed March 25, 2021. Colonias are peri-urban or rural neighborhoods that have been a public health focus of community advocates, government agencies, elected officials, and residents for over three decades due to their high poverty rates, lack of basic infrastructure, and substandard housing.2Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas “Las Colonias in the 21st Century: Progress Along the Texas-Mexico Border,” Jordana Barton et. al., accessed March 25, 2021. Cameron County and the area surrounding Brownsville have some of the highest concentrations of colonias on the border.

When we conducted our colonias study, we were looking at the forms of infrastructure that are typically considered when studying these unincorporated areas: safe drinking water, wastewater, paved roads, drainage, electricity. We did not include any questions about broadband infrastructure. However, in each of the focus groups we conducted across six border counties, the residents shared stories of how lack of internet access was limiting their children’s ability to do their homework and their own ability to participate in workforce training and job opportunities. In the colonia study report, we cited the digital divide as an area that was impacting educational outcomes and economic opportunity. The lowest-income residents of the border region made it clear to us that broadband is essential infrastructure, like roads, water, and electricity.

When I first analyzed US cities with 50,000 or more households in 2018, I found Brownsville ranked as the worst-connected city in the country with the least access to fixed broadband.3Author’s analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2016. Subsequently, in the National Digital Inclusion Alliance (NDIA) 2020 ranking of cities, Brownsville was once again ranked as the worst connected. According to NDIA’s analysis of 2019 American Community Survey data, 67 percent of households in Brownsville lack a fixed broadband subscription.4Paolo Balboa, “Worst Connected U.S. Cities of 2019,” National Digital Inclusion Alliance, September 17, 2020.

Local Leadership

During the summer and fall of 2019, the City of Brownsville, with the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, convened community stakeholders to come up with a plan to address the pressing challenge of the digital divide that is prevalent in the City and region. In doing so, Brownsville has recognized that the entire economy is transitioning into a digital economy, and that local leadership and community engagement are required to expand existing broadband infrastructure. Leaders have also realized that, in addition to adequate and strategically placed public fiber, they must create a plan to address and fill the other gaps in access that exist in the community: affordability of subscriptions, devices, and tools and digital skills training and technical assistance.

The large gaps in digital access are a sore spot for elected officials. In his 2019 State of the City address, Brownsville Mayor Trey Mendez stated, “Access to Broadband will determine our future …I’ve heard many stories that [students], the future leaders of our community, struggle with not having access to the internet, whether it’s because of affordability or just lack of infrastructure to their homes. This is unacceptable.”5Brownsville Mayor Trey Mendez, State of the City Speech, 2019.

In a show of commitment, the following stakeholders each contributed to fund a broadband community assessment and a strategic engineering study: the City of Brownsville, Greater Brownsville Incentives Corporation, Brownsville Community Improvement Corporation, Brownsville Public Utilities, Port of Brownsville, Texas Southmost College, Brownsville Independent School District, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, and Methodist Healthcare Ministries.

Transition from Analog to Digital Economy

Brownsville, like the rest of the US–Mexico Border, has historically been seen as a gateway for international commerce and trade, as well as the exchange of ideas and cultures. These characteristics have been coupled with the infrastructure to make that happen: steamships to New Orleans and Veracruz, railroads into Mexico, international bridges. However, the future of commerce and culture no longer depends on traditional transportation infrastructure like railroads and highways, but on broadband infrastructure. Given the lack of broadband infrastructure in Brownsville, public investment is needed to bridge the gap.

We are in the midst of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, and the internet has introduced an information technology transformation, making way for the exponential growth of the digital economy. The internet is the electronic platform for the digital economy that is enabling new online business models that are displacing traditional brick-and-mortar businesses. The ability to reach customers without geographic boundaries, coupled with a transformation in computer processing power, has created economic opportunities and operational efficiencies never before imaginable. The digital economy already accounts for hardware, software, and application tools that did not exist in the analog economy. Broadband infrastructure (fiber optic cable coupled with high-speed wireless technologies) is the foundational infrastructure for the digital economy, and for attracting industry (i.e., jobs) to the region.

The digital divide is a result of the broadband market structure in the United States. It exists because private internet service providers (ISPs) do not have economic incentives to deploy broadband infrastructure to low-income urban and rural areas or low-density suburban and rural communities. ISPs do not deploy broadband infrastructure in these communities because they are not able to recover their cost of deployment and/or return on investment that their investors demand.

Even if widespread broadband infrastructure existed, the digital divide would persist because a substantial percentage of households are unable to afford a broadband subscription due to high prices. Consumer prices for broadband are high in the US compared to other advanced economies. According to economist Thomas Philippon, who compared the monthly cost of internet service in industrialized countries, while South Koreans pay an average of $29.90 and Germans $35.71, people in the US pay $66.17. These are unbundled internet prices for stand-alone internet service.6Thomas Philippon, The Great Reversal: How America Gave Up on Free Markets (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2019).

Given this market structure, the private sector will not deploy broadband infrastructure throughout a low-income community like Brownsville. Therefore, without public investment in broadband infrastructure, the City will not be able to create economic opportunity pathways needed for success in the twenty-first century. Broadband infrastructure is the highway system of the digital economy.

Digital Inclusion Strategy

With the issuance of a request for proposals in 2020 and the hiring of a broadband engineering and network design firm Lit Communities, Brownsville is taking steps to developing a digital inclusion plan for the community. This plan includes the development of a community survey, a broadband infrastructure deployment model, and digital equity programming.

The community survey and needs assessment will guide Brownsville’s broadband expansion strategy. Residents’ input will be used to answer the following questions and more:

1) Should fiber infrastructure be deployed to provide broadband service for commercial customers and/or residential customers? Under what model?

2) What is the solution to closing the homework/remote learning gaps that have been so clearly exposed during the COVID-19 pandemic?

3) Is there consensus that the City should close the digital divide more broadly?

4) Given the importance of the healthcare industry in creating jobs in the region, as well as the pressing need to address serious local health disparities, does the community want to develop a special effort around telemedicine?

5) What other priorities does the City have for public safety, public health, and economic resiliency in the face of natural disasters, pandemics, and climate change?

Answering these questions will determine what broadband models should be adopted. Some of the options: building government-owned middle-mile fiber network, with a public–private partnership covering the last mile to residents and businesses; the City becoming an ISP; using public fiber transport to deploy private wireless networks in low-income neighborhoods.7Forthcoming publication, Benton Institute for Broadband and Society, “Closing the Homework Gap Permanently with a Private Wireless Network Solution,” by Jordana Barton and Gabriel Garcia, 2020.

By the time any network is deployed, the city and stakeholders will need a digital equity plan. This can consist of basic digital literacy training programs and workforce retraining for the digital economy, and supporting the creation of a Digital Inclusion Alliance. Ultimately, the digital inclusion plan will be incorporated into the City’s economic development plan.

The current efforts the City of Brownsville and stakeholders are undertaking to close the digital divide will ideally create a resilient community and potentially transform the local economy. This effort to remove a structural economic barrier can go a long way in breaking the cycle of persistent poverty that currently characterizes the City and border region.

Biographies

is vice president of community investments at Methodist Healthcare Ministries. Previously, she was a senior advisor at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, where she supported the Federal Reserve System’s economic growth objectives by promoting community and economic development and fair and impartial access to credit. Her focus areas include the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA), community development finance, digital inclusion, financial education, affordable housing, workforce development, and small business development. She authored or coauthored the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas’s publications “Las Colonias in the 21st Century: Progress Along the Texas-Mexico Border” (2015), “Closing the Digital Divide: A Framework for Meeting CRA Obligations” (2016), and “Preparing Workers for the Expanding Digital Economy” (2018). Barton grew up in the rural South Texas community of Benavides. She holds an MPA from Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.