The relocation of Taro Island

As rising seas threaten the Solomon Islands, one community is planning a move to higher ground.

October 1, 2019

The site of the old market, now under water, from Taro Island Wharf. The beach once extended to the front of the boats. Credit: Emma Benintende

The Deborah J. Norden Fund, a program of The Architectural League of New York, was established in 1995 in memory of architect and arts administrator Deborah Norden. Each year, the competition awards up to $5,000 in travel grants to students and recent graduates in the fields of architecture, architectural history, and urban studies.

Emma Benintende received a 2018 award.

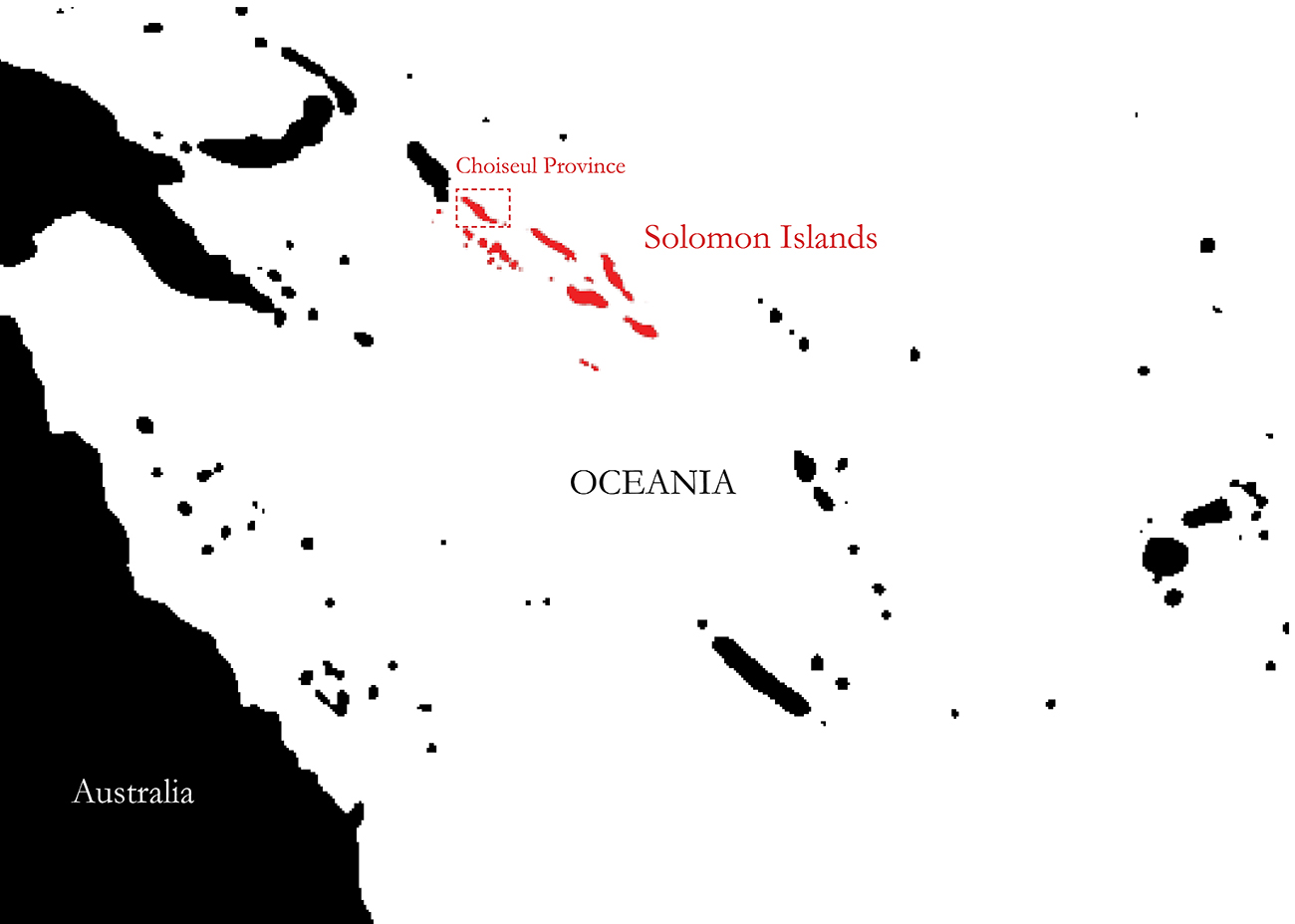

At high tide, waves lap the gnarled roots of the centuries-old trees along the coast of Taro Island. Idyllic beaches that were once the site of family picnics and afternoon fishing trips are now submerged under several feet of turquoise water. While climate change–induced sea level rise is impacting coastal cities worldwide, the rate in the Solomon Islands—a Small Island Developing State (SID) of 600,000 people on nearly 1,000 islands southeast of Papua New Guinea—is three times the average rate of sea level rise worldwide. Residents of the country’s lowest-lying islands are now faced with a critical decision—whether to fight the constant threat of flooding and associated risks, or move to higher ground.

The largest of these vulnerable communities is on Taro Island, one of nine provincial capitals in the island chain. The national government in Honiara designated the 100-acre island of Taro, located less than a mile from the landmass of Choiseul (or Lauru to locals), as the capital of the newly created Choiseul Province in 1992.

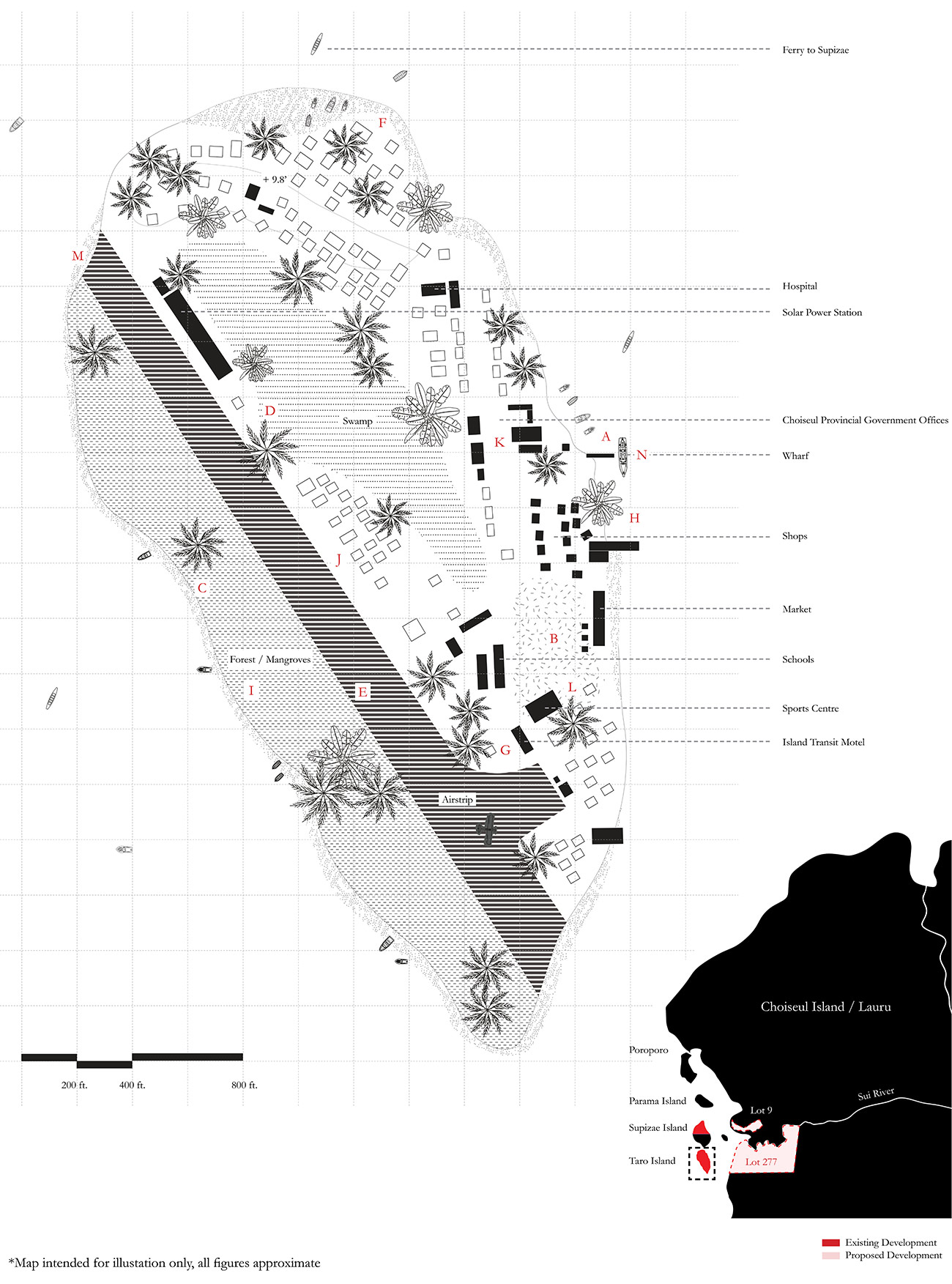

Despite its small size and precarious elevation less than ten feet above sea level, officials had little choice. The island already had more vital infrastructure—a grass airstrip and medical clinic—necessary to serve the province’s 26,000 inhabitants than any other town in the region. Situated at the northern end of the Solomon Island chain, it is also a gateway to the country along international shipping routes that connected Southeast Asia to larger cities of Gizo and Honiara further south.

Finally and crucially, the island rested on federally held land. On many Pacific Islands, land is held by customary owners, and procurement for public use can be a long, complicated, and costly process.

From its founding, the government recognized Taro’s limitations and recommended that it serve as a springboard for Choiseul Bay Township, a future expansion on the main island. While the Choiseul Provincial Government (CPG) sought to secure land from customary owners on the main island, unchecked development spread across the largely uninhabited island.

Today, the island community of 800 to 1,200 residents is at a crossroads. For over two decades, Taro Islanders have struggled to mitigate the effects of the rising water and adapt to changing environmental conditions. But as the population swells and the island cedes ground to the sea, the residents of Taro are firmly committed to relocating their capital to higher, drier ground, believing it is the only way forward.

Choiseul Provincial Government Headquarters, located less than 50 feet inland from the shore. Credit: Emma Benintende

Geoffrey Pakipota, Provincial Secretary of Choiseul, noticed the rising sea just a few years after accepting his first official post on Taro in 1993. At the time he couldn’t identify the cause. “We are used to seasons with very big tides, but we thought this was something strange or extraordinary,” he recalled.

Roswita Nowak, a physical planner for the CPG in the late 1990s and early 2000s, made similar observations. “First a bench came down, and the water rose a little, and a little bit more.” She recounted efforts to rebuild a beach along the northeastern coast near the hospital. A breakwater was constructed 50 feet out into the sea to capture sediment and restore the shoreline. Officials also installed barriers—sandbags, gabions, and walls of coral boulders—to protect the beaches and to encourage sediment deposition around the island.

Despite some success with these projects, the CPG has rejected further land reformation and hard infrastructural measures due to a lack of labor, timescale, and because the same blockades that prevent erosion in one area may exacerbate the problem in others. A 2014 study conducted by Australian engineering consultancy BMT Global (formerly BWT WBM) indicates that without efforts to mitigate inundation, sea level rise could claim 5 to 20 meters—or 3 to 12 percent of the island’s landmass—by 2055, and 20 to 50 meters by 2090.

Flooding is not the only threat to Taro. Several interconnected, incremental, but persistent changes caused or exacerbated by climate change will affect daily life over the next few decades. As global average temperatures rise, the clearing of trees for development on Taro has left residents vulnerable to unbearable heat.

Ongoing development along the Taro Island airstrip. Due to the availability of local wood, most homes are timber-framed with concrete imported from Honiara. Credit: Emma Benintende

The risk of saltwater intrusion into the island’s freshwater swamp rises with the sea. Malaria-carrying mosquitoes thrive in brackish water, intensifying an existing health risk on the island. Because there are no sources of clean fresh water, residents depend on rainwater tanks for drinking, cooking, and bathing.

Rainwater catchment tanks at the Island Transit Motel. Rainwater is the only potable source of fresh water on Taro Island. Credit: Emma Benintende

Unpredictable rainfall patterns put the entire island at critical risk of dehydration and lack of sanitation. These erratic climatic conditions, coupled with a scarcity of arable land, may contribute to food insecurity and a critical waste management problem as residents increasingly rely on packaged foods and bottled water.

The west bank of the swamp, Taro’s only freshwater body, used as a dumping ground in the absence of a landfill. Credit: Emma Benintende

While these hazards alone might warrant the relocation of a portion of the population, it is the existential threat of catastrophic natural disaster that convinced islanders to leave their homes on Taro behind.

In April 2007, an 8.1 magnitude earthquake 100 miles southwest of Taro triggered tsunami warnings. Residents scrambled to evacuate to high ground on Choiseul Island, but as they guided their boats across the bay, the waters of the lagoon receded, leaving whole families stranded on shallow reefs. When the wave came, the people were thrust back to shore, barely managing to keep their boats upright. While Taro Island sustained no major damage, the tsunami killed six in Choiseul Province and left indelible fear in the community.

Though climate change does not affect the frequency or severity of earthquakes, rising sea levels make low-lying land increasingly susceptible to tsunamis. A single wave could overwhelm Taro in seconds. The Solomon Islands National Climate Change Policy (2012) predicts a 0.3 inch (7.7 mm) increase in sea level each year, increasing the threat of tsunami with the passage of time. The island’s highest point, just under 10 feet above mean sea level (MSL), is a 5-acre hill at the northern tip of the island. Models indicate that by 2030, the peak water level of a 100-year tsunami would be over 10.7 feet MSL, rising to 12.8 feet MSL by 2090.

In January 2013, the Choiseul Integrated Climate Change Program (CHICCHAP), organized by the Solomon Islands national government, brought international agencies, development partners, and NGOs to Taro Island to plan adaptation strategies and encourage resilience to environmental degradation and natural disasters in Choiseul Province. The program introduced the community to the science of climate change, providing an explanation for the environmental changes that residents had been observing for over a decade. CHICCHAP outlined several initiatives, or “Projects in Partnership,” including an effort under the Pacific Australia Climate Change and Adaptation Programme to develop an Adaptation Action Plan and Master Plan for Choiseul Bay Township. Two decades after the CPG first proposed Taro’s expansion to the main island and six years after the Gizo tsunami made relocation an imperative, plans for the new town finally began to take shape.

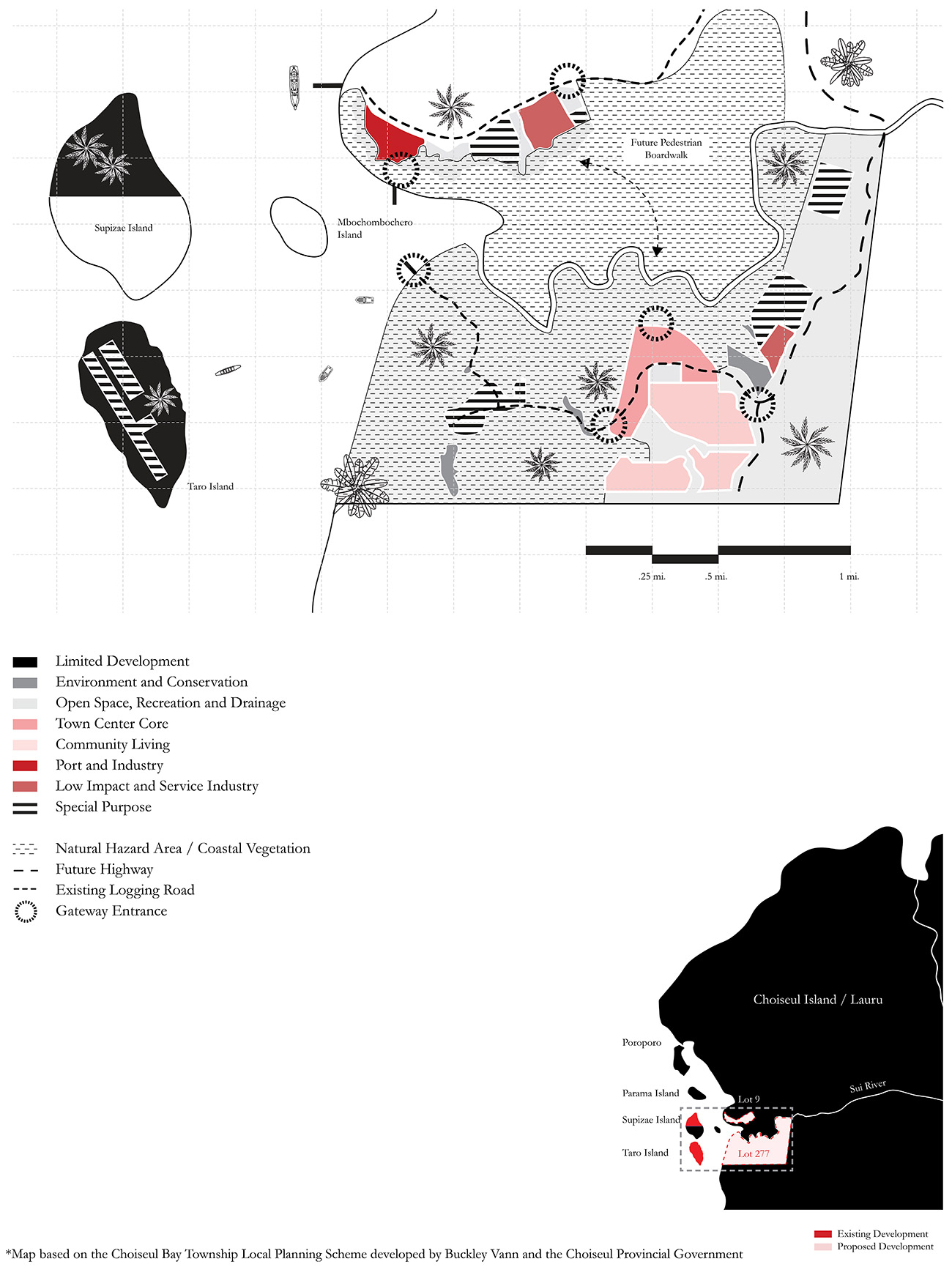

The CPG acquired Lot 9, a long, narrow, rocky stretch on Choiseul in the early 1990s, but securing additional land proved difficult. After twenty years of negotiation, the CPG finalized the purchase of Lot 277, the second parcel for Choiseul Bay Township in December 2011. The two detached sites, straddling the Sui or Mulambull River, cost over a million dollars (USD), a sum several times greater than initial estimates. Lot 9, which sits at a secure 50 feet above MSL, has some existing development: a jetty, boarding school, light industry, and a few residences. Across the Sui to the south, much of Lot 277 is low swampland, still susceptible to sea level rise and tsunami risks. While a significant portion of Lot 277 will have to remain open or recreational space, the two lots provide ample acreage for expansion, easier access to high ground, and a reliable supply of fresh groundwater and river water.

Working on behalf of the Australian Department for the Environment, a team from Brisbane—scientists from the University of Queensland, engineers from BMT Global, and urban planners from Ethos Urban (formerly Buckley Vann)—visited Taro Island four times between January and June 2014. The team collaborated with the CPG to assess the environmental hazards and risks on the island and relocation site, and to work with local communities to develop a strategic framework for relocation. Community engagement was central to the team’s work, and rigorous outreach ensured that the strategic planning document reflected the needs, ambitions, and desires of not only Taro Islanders, but people from across the region who rely on the capital for goods and services. Engagement methods ranged from face-to-face interviews to group workshops and meetings to public presentations. Because English is a third language for many Solomon Islanders—after one of several Indigenous Melanesian languages and Solomon Islands Pijin—the group worked with translators and printed posters and informational booklets in English and Pijin.

Visual tools were integral to the collaborative planning process. To elicit feedback, the team laid tracing paper over risk maps to demonstrate to the community how to plan land-use areas around potential hazards. The Australian experts provided a comprehensive overview of environmental hazards and the impacts of natural disasters that computational models predicted over time, but it was the CPG and community members who completed the risk assessment by explaining which buildings and infrastructural assets were most critical and describing how coastal erosion and sea level rise were already affecting the island. Local involvement was also crucial to the land-use planning exercise that became the foundation of the Choiseul Bay Township development plans. The community helped the team identify appropriate locations on Lots 9 and 277 for fishing, subsistence gardens, pig hunting, gathering building material, and cultural sites, and described the kinds of spaces—building and landscape—they hoped to see in the new town.

The Australian team drafted three schemes for the community to review before finalizing its strategic plan in June 2014. Based on a combination of environmental assessments, community and CPG feedback, and best practices, the Draft Local Planning Scheme (LPS) laid out a seven-point vision for the new town. Choiseul Bay Township would be a “provincial, prosperous, safe, clean and green, living, connected, and well-serviced” town.

The plan marked Taro and Supizae for limited development, with the airstrip and landfill to remain the only active uses on the two islands. A wharf on Lot 9 would be the relocated capital’s primary port, with an industrial area, a telecom tower, fuel storage, and waste transfer nearby. Opposite a green buffer zone, the lot would also host a new hospital, medical staff residences, and low-impact industry. Due to its hazard susceptibility, much of Lot 277 would be open/recreational space with a water treatment plant and second waste transfer station. Higher ground away from the coast would provide a community living area and the provincial government headquarters. Because the two lots are not physically connected, the existing logging road network would be expanded to service the town and additional customary lands would be secured to accommodate a pedestrian boardwalk connecting the two parcels.

The CPG relied heavily on this draft LPS for its final version of the document, which was required by the national government to secure technical and financial support from federal ministries and international partners. At the end of 2016, the national government gazetted, or approved, the LPS, a major milestone for the realization of Choiseul Bay Township.

However, nearly three years after the LPS was approved, Lots 9 and 277 appear untouched—a horizon of impenetrable bush as far as the eye can see from the wharf on Taro Island. CPG’s social media accounts are flooded with requests for information about settlement on the new site. Officials are eager to move forward, but they are also wary of the poorly managed and unregulated development that plagues larger Solomon Islands cities like Honiara and Gizo. They believe there is a different way forward. “Things cannot happen quickly because we need to make sure that things are done correctly,” Roswita Nowak insisted. Geoffrey Pakipota, who has devoted much of his public service career to the realization of Choiseul Bay Township, is determined to build a modern, “clean, green, town”—a model of responsible and sustainable development for Solomon Islands and its Pacific neighbors. For Choiseul leadership, there is a moral imperative for the new capital to be distinct from the kind of wasteful and shortsighted development that has caused and continues to contribute to climate change. Though the vision of the CPG is admirable, its dream is unattainable without strong national support and international assistance.

Before construction of Choiseul Bay Township can begin, the CPG must complete feasibility studies and technical assessments for key infrastructure—roads, water, power, waste and wastewater management—as well as a subdivision plan. Due to the limitations of local labor and expertise, each of these undertakings requires the cooperation of national ministries with the resources to oversee basic development. Choiseul Bay, however, is meant to be unlike any other city in the Solomon Islands, and the experience, competence, and technology required to develop an urbanistically and architecturally complete master plan for an environmentally, socially, and financially sustainable modern city will likely have to come from overseas.

Taro Island has many sponsors. From the new Premier’s Residence and the Sports Centre to the hospital’s emergency boat, water tanks, and even garbage cans, foreign aid provides critical support to a province with few resources to fund its own development, improvement, expansion, and now relocation. In the past, aid organizations have had difficulty implementing projects in Choiseul because they have not made meaningful connections with local communities to help them understand the importance and relevance of the aid work. Any aid, from technical consulting to urban and architectural design, must be done in close consultation with the provincial government and the community as a whole. The CPG and Taro Island do not wish to be the passive recipients of international aid, but active and equal partners in the planning of Choiseul Bay Township.

Rising waters are not the only change that the developed world has brought to Taro Island. Recently installed solar panels provide 24-hour electricity to the island for the first time, a proposed undersea telecommunications cable from China would bring more reliable mobile and internet connectivity, and increased trade has opened up larger markets for imported goods and packaged foods. “Whether we like it or not, development is coming and the world is changing. We need to try to open up to meet the standard, to improve our living,” said Roswita Nowak. Choiseul Bay Township is not a re-creation of Taro Island on a new site, but an opportunity to build a better town, one that redirects the forces of modernization into improved and expanded infrastructure, services, and spaces for a growing population.

In the context of relocation, architecture is not just about placemaking and aesthetic considerations, but about establishing standards for safe, sustainable growth. Even on the new site, Taro Islanders may still have to contend with hazards including flooding and tsunami. Working in concert with engineers, architects can contribute to updated standards for resilience to environmental threats. Elevated homes oriented away from the shoreline with stronger and deeper pilings and structural redundancy are more likely to weather tsunamis and cyclones. The Ministry of Lands, Survey, and Housing standards should be revisited and CPG officials trained to ensure that these building standards are implemented on public projects, and that residents are advised on how to apply standards to private development. Building design can contribute to a community’s ability to survive catastrophic weather events, but also slow-moving threats: Screens can protect inhabitants from mosquitos and efficient drainage systems and secure retention tanks can catch rainwater as backup for centralized water systems which may be compromised by earthquake or contamination.

Relocation requires us to consider whether communities are defined by social ties, or whether the relationship between the residents and the physical characteristics of the place they inhabit defines the identity and contributes to the cohesion of a community. Designers, planners, and engineers involved in these projects must ask themselves: Are people bound to people, or are people bound to place? For many Pacific Island communities from the Carteret Islands, Kiribati, Tuvalu, and Fiji, connections to land date back countless generations and the idea of relocation is traumatic. Founded less than a century ago, Taro Island is important as an administrative and economic regional hub, not as an ancestral home. Though few residents have familial or traditional attachments to the island itself, many are accustomed to ways of living that may not be possible on the Choiseul Bay Township site. For example, life on Taro revolves around the sea—boating, fishing, and swimming. However, on the new site, the community living areas are set back from the coast. Residents will have to find new places to store their boats and recalibrate their lives to this new environment. Architectural and urban representation can help the community understand what those changes are and how they can adapt.

In addition to planning expenses, Choiseul’s remote location and extreme climate increase the cost of labor and transporting building material. Last year, the federal government in Honiara allotted no funding for the relocation project, likely due to the lack of visible progress over the preceding two years. While the provincial government is eager to find international donors and has had preliminary conversations with foreign representatives and aid organizations, it cannot supercede the national government. It is ultimately the responsibility of leaders in Honiara to sell the effort to potential sponsors.

One thousand five hundred miles away, Fiji has become a global leader in relocation policy and practice. In February of this year, the Ministry of Economy’s Climate Change Unit released the world’s first Planned Relocation Guidelines. To date, the country has completed three full relocations of coastal villages threatened by rising sea levels. Though these projects—villages of no more than 200 people—have been much smaller and simpler than the resettlement of Taro to Choiseul Island, Fiji’s guidelines and institutional relocation framework offer templates for similar efforts in the Solomon Islands. The guidelines prioritize a transparent, inclusive, community-driven process to achieve long-term economic and environmental sustainability. The Fijian government also created a national relocation task force committee comprising representatives from all relevant ministries to streamline communication and coordinate these inherently multidisciplinary efforts.

In Louisiana, Isle de Jean Charles began planning for resettlement in 2010; in coastal Alaska, several villages, including Newtok, Kivalina, and Shishmaref, have elected to relocate, though their plans are languishing in a bureaucratic morass as the melting permafrost continues to jeopardize critical infrastructure, homes, and businesses. Within our lifetime, parts of Boston, Charleston, New York, the Bay Area, and Miami are expected to face serious climate change–related flooding and associated natural disasters. Large and well-publicized efforts like Rebuild by Design and Resilient by Design propose numerous creative hard and soft infrastructural solutions to mitigate the effects of climate change and clever adaptation strategies that encourage aquatic living. Yet with recent projections indicating at least a foot of sea level rise is all but inevitable along US coasts over the next 50–100 years, relocation or “managed retreat” must be considered a viable option, and it is in the world’s best interest to encourage, invest in, and learn from these pioneering efforts. Granted support to realize its relocation, Choiseul Bay Township could become a model for the Solomon Islands, the Pacific, and the global community.