Writing the program

By Mark Robbins

In 1987, the League collaborated with the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development to launch a design study on the potential of small-scale infill housing to contribute to the city’s affordable housing needs. The Vacant Lots project culminated in an exhibition and publication, portions of which are republished here on archleague.org.

In the following essay from the 1989 Vacant Lots publication, architect and member of the organizing committee, Mark Robbins discusses submissions that address social programs and consider the housing needs of non-nuclear families and disenfranchised populations.

The desire of architects to address social programs in their work is not new, though in the past ten years discussion of this issue has seemed muted. Vacant Lots urged designers to ask questions about subsidized housing: who uses it; how is it occupied; and how is the community affected?

Many of the seventy projects submitted respond to these issues with impressive specificity. They address the needs of families that are increasingly non-nuclear and of disenfranchised groups living in urban areas where neglect has been less than benign. Attention to a complete constellation of social and political needs is in evidence: outdoor public spaces, day care, vocational training, and innovative unit mixes are some of the facilities proposed for the benefit of the residents and the communities into which they are integrated.

Breslin/Mosseri Design, Site 8 | click for an excerpt from the project statement

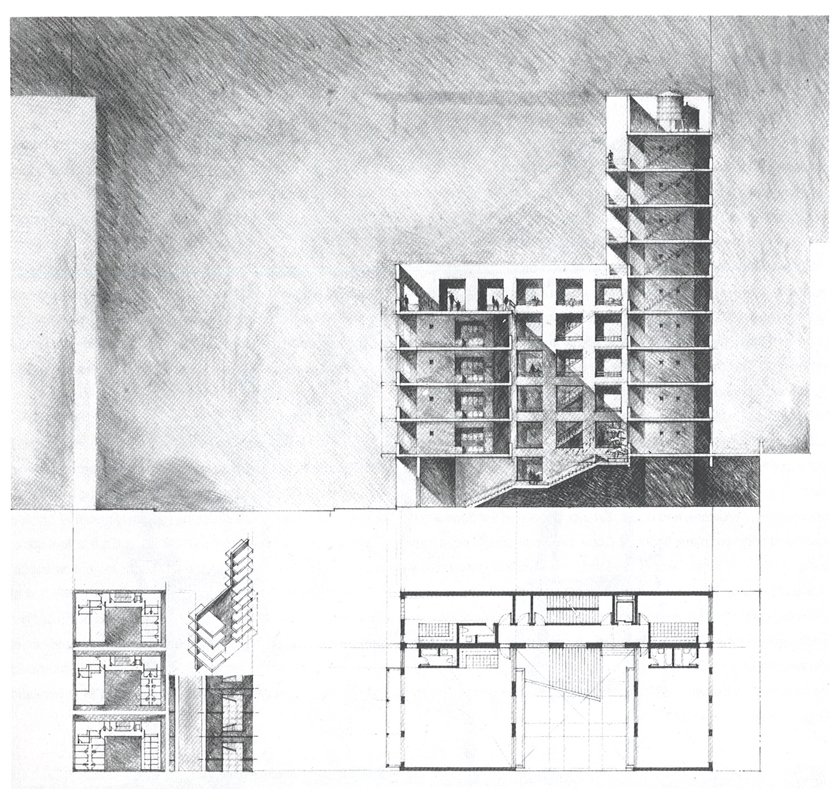

Several schemes rethink the private enclave of traditional housing, choosing not to replicate the typical spatial configuration of the house. Maintaining that less space is more humane than no space at all, the project by Kim, Martin and Mattarese for Site 5 combines traditional apartment units with “negotiated spaces” — rooms used on a temporary basis, clustered around common facilities of kitchen and bath. “Shared living spaces” adjoining separate bedroom suites in Blake and Skowronek’s project for Site 6 allow use by extended families and separate family groups. Along these lines the striking scheme of Breslin/Mosseri for Site 8 revives the boarding house as a type. Single individuals rent rooms within the two large houses which offer suites of three or four bedrooms. A small community is created internally as a buffer to an often strange and hostile city outside.

Implicit in these shared-room schemes is an assumption of the unit mix as responsive to a community’s needs. Certain projects focus on this idea. Tony Tsirantonakis’ grandmother/mother/daughter house for Site 8 in Queens nests telescoping units, acknowledging this important type of extended-family household. On Site 3 Jin Kim proposes housing for single persons and single-parent households, citing convincing census material to support this need. Recognizing, however, the constant evolution and change within New York neighborhoods, the team of Weiss and Manfredi proposes two loft buildings built around an open court on Site 7. The space is planned to be flexible to the “changing definitions of local housing needs, SRO, single family dwelling, et al.” as defined by floor, building, or both.

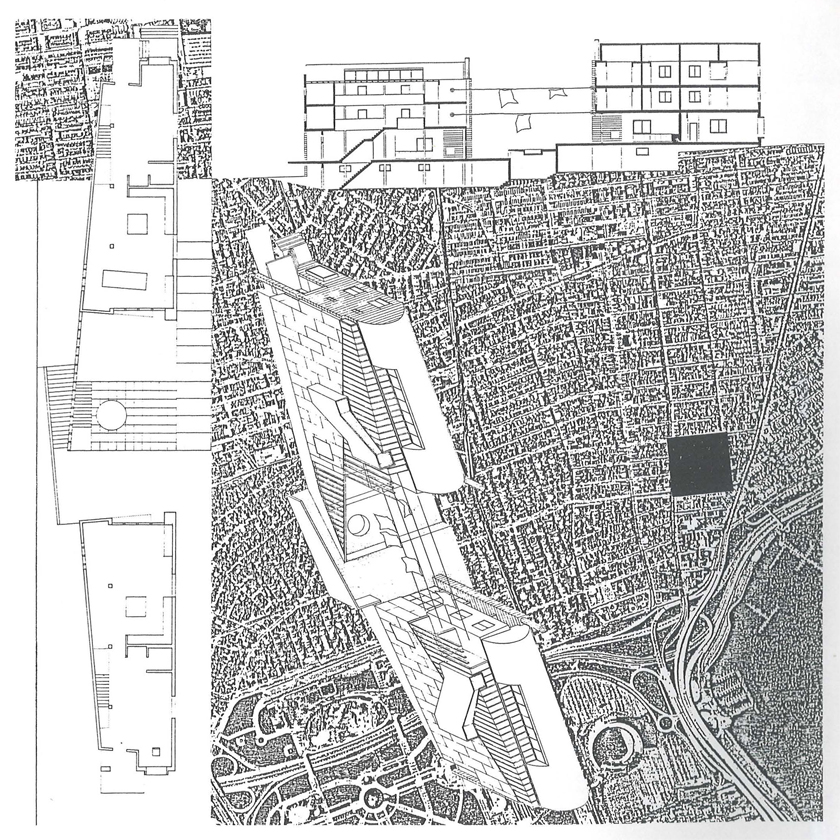

Marion Weiss & Michael Manfredi, Site 7 | click for an excerpt from the project statement

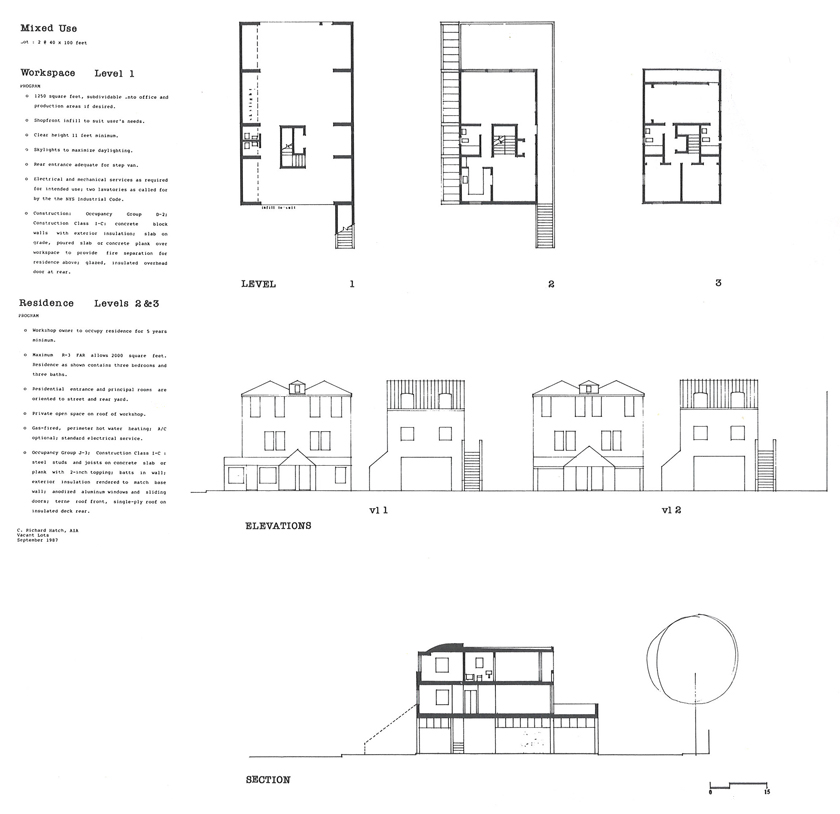

Other projects address the economic depression of the neighborhoods in which they propose to build. Training centers, workshops, and sewing rooms, for example, are proposed in concert with residential units. Employing the traditional front-house / back-house form, Fairbanks and Jaffe design buildings for Site 4 that act as gateways to the back portion of the lot where work pavilions are located. Their placement of work-centers at the end of a sequence of public spaces encourages a mix of residents within the community at large. For Site 10 Richard Hatch proposes a contiguous working and living space with a shopfront for use by the workshop owner and a workshop of 1250 square feet that could accommodate four to six workers. Hatch’s proposal also calls for the enactment of mixed-use zoning and “enterprise zones” to encourage this type of development. The scheme positively recalls the model of the family living above the store of earlier immigrant groups.

Many of the projects contain a component for community outreach. Nathaniel Coleman asserts the diversity of underrepresented groups on Site 5, proposing an emergency shelter with 24-hour staffing, as well as a mix of one, two, or three-bedroom units and six one-bedroom units for the elderly; in addition, the top floor provides space for twenty boarder babies. The building has common dining spaces and tenant counseling facilities on site. A more specialized facility is conceived by Jim Kettig for Site 10. His “group house” would create a therapeutic community of adults and adolescents and provide care for both first and second-generation drug addicts. Also of interest in this scheme is the contact made by the architect with local drug rehabilitation groups during the design process.

C. Richard Hatch, Architect, Site 10 | click for an excerpt from the project statement

The project of Lee Ledbetter and Gustavo Bonevardi, in collaboration with Linda Baldwin, planner, James Lay, clinical psychologist, and Morgan Hare, contractor, responds to a more recent, but no less tragic fact of urban life in New York: homeless persons with AIDS. Their design strategy attempts to integrate persons with AIDS back into their own community. Individual rooms open onto commonly used facilities, such as dining, recreation, treatment, and counseling.

Many questions arise from these schemes about initial assumptions and the mechanism for implementation. Who, for example, decides on the unit mix and who gets the available space? What type of residential therapies work? Which planning and zoning decisions will be truly beneficial to the long-term health of a community?

The immediate mission of the City is to house the greatest number without preference for specialty groups — this is a luxury we are told we cannot afford — but certainly, questions about the composition of this generic “mass” to be housed call for study as well as construction.