Interview: Williamson Chong Architects

Donald Chong, Betsy Williamson, and Shane Williamson founded Toronto-based Williamson Chong Architects in 2011 with a commitment to “context, materials research, economies of construction, building performance, and client-based collaboration.” Their work ranges in scale from furniture to master planning, and demonstrates a particular interest in what the firm terms “Incremental Urbanism,” a strategy that mines the potential of often irregular urban building sites — evidenced in the Galley House and the Blantyre House, both in Toronto, as well as their current projects the Bala Line House and the Grange-Triple Double multi-family dwelling. The firm’s work also includes the House in Frogs Hollow, Greys Highlands, Ontario; and the Abbey Gardens Food Community master plan in Haliburton, Ontario, which begins construction in 2015. In March 2014, on the occasion of their Emerging Voices lecture (video embedded below, also available here), Chong, Williamson, and Williamson sat down with League Program Director Anne Rieselbach to discuss their practice.

Anne Rieselbach: This series emphasizes the voice of practitioners. How would you describe your voice?

Shane Williamson: As an office led by three partners, we certainly each have our own distinct interests and voices. One could characterize Don as the optimist, I’m the pessimist, and Betsy straddles both lines, which creates a fairly charged environment in the office. So it’s very curious to see how those interests come together. The challenge is to maintain a critical practice that is also a professional practice, in which clients can bring projects to us and feel confident that our criticism doesn’t alienate their own desires.

Donald Chong: At its best, our critical work has no distinction to our built work. That’s obviously an ideal condition for most practices, but I think as we get closer and closer to finding that sweet spot we understand that there is no A drawer and B drawer. That’s a project unto itself in the office: balancing client interests with our architectural voice, so that the challenges of what we need to do and what we want to do may actually become the same thing. To be good and responsible, they should be the same thing.

We also embrace our role as a smaller practice and our ability to take risks and to explore. We believe that the smaller, younger practice has a role in architectural discourse and that our production has reach.

Betsy Williamson: When you start your own practice, you’re often waiting for projects to come to you. But you start to realize that if you let the projects that come to you define your practice, it may go in a direction you’re not particularly happy with. We want to shape our practice in a really purposeful manner. So we actively engage with the city and try to shape the work that comes into our office before the projects are fully defined.

Bala Line House | Photo by Bob Gundu

AR: As an emerging firm, what do you see as the advantages and challenges to practicing in today’s economic, professional, and intellectual climate?

BW: Economically, Toronto has been truly blessed in the last number of years, as we didn’t experience the financial downturn the way you did in the States. In terms of the day to day, the work that keeps our office cooking is the residential work. Land values in Toronto are so high that more people are staying in and improving their homes as opposed to selling and upgrading. This allows us to pursue alternate projects, such as Abbey Gardens, that allow us to chip away at big ideas over a very long period of time.

SW: We also recognize that our diversity — whether in race, gender, academia, or practice — is meaningful in terms of our agility and our ability to relate to a particular client. This has proved to be very useful for us in this economy and with the range of clients that come into our office. Diversity of practice plays such a significant role in making people feel comfortable and keeping us flexible.

AR: You outline your design approach as privileging “specificity of context, materials research, economies of construction, building performance, and client-based collaboration.” That doesn’t seem to leave room for much else. Can you elaborate on what that means and can you trace the sequencing of these factors in the design and planning of a project?

SW: First of all, we hate writing those statements, particularly the ones on our website, because they are supposed to be inclusive in order to demonstrate that we have a wide set of interests. Yet they are also a bit of a disclaimer for specificity of process. When a client expresses an interest, such as in a material — “I love wood,” or “I love stone” — then that specificity says that from that point forward the process is going to be dedicated to exploiting that interest. By establishing our methodologies, we’re declaring that the critical aspect of architecture and discourse is significant, and the client understands that we will be bringing that criticality into the project.

House in Frogs Hollow | Photo by Bob Gundu

DC: As architects, we’re really trying to understand where our project begins, if you will, recognizing the fragile state of all the different elements — the client, the site, the finances, and so forth — that must come together. We try to cradle each project early on. Our role is not simply the classic or contractual notion of what an architect is, but that of a catalyst. We see our role as stewarding a project from its inception, and as an office we feel very comfortable in the ideas generation phase because we approach it as a co-authoring process.

BW: Ultimately, we want to make really beautiful, long-lasting pieces of architecture. We invest in material research, sustainability, and detail, and have fostered long-standing relationships with contractors. The materials conversation comes through balancing our client’s desires, the budget, and our own interest in durability and longevity. We often know what material we’re working with before we even start formal manipulations of space or site strategies. Often for the things that you touch, such as door handles, we use a lot of natural materials because they seem to have this longevity. They embody this kind of soul.

AR: Let’s step back now to your work within the city. Could you talk about your interest in what you call “Incremental Urbanism?”

DC: The city has only so many spatial offerings, and many of our projects are in leftover spaces or infill properties. We see these spaces in the aggregate, and that with “incremental” projects we can do work that doesn’t just speak to itself or its own property. We believe that you are a bigger piece of your community than you think, even though you may only be on a 20-by-120-foot piece of property. The Small Fridges Make Good Cities project, for example, spoke to the idea that the choices we make in our own homes, even how much food we keep, affects the larger collective and can create investments back into neighborhoods and Main Streets. The fruit bowl is a fruit bowl again because you’re actually replenishing it by going out to meet the neighbors and vendors and so forth.

BW: It’s about increasing density. When you increase density, you develop a contemporary language for living in the city and for urban form.

SW: We’re sitting at this table in New York right now, so our conversations about density should be seen as relative. Toronto has a relative density; there are still choices to be made and people have the ability to purchase larger lots to decrease density. In some situations, we’re manufacturing density in a context that is, at times, resisting it. In New York, these aren’t choices — the fabric is dense.

Galley House | Photo courtesy of Williamson Chong Architects

AR: What are the volumetric considerations entailed in working on such compact or irregular sites?

BW: A key challenge is how to get light in the center of a building that is 60- to 80-feet long and has no windows on either side. There are a couple of ways we’ve addressed this, including volumetric scoops cut from the side, which meet zoning and fire regulations while still allowing light in in a very generous way. Directing light from skylights through double-height spaces and bouncing it off of planes is another strategy that formally guides these projects.

SW: Volumetrically, getting a good section is very difficult because you want as large a floor plate as possible and so the notion of double-height space — notwithstanding the issue of light — becomes a real challenge. For so long, contemporary modern architecture in Toronto has always been about flat roofs. Yet the city just implemented a controversial bylaw that essentially permits a much taller house if it has a pitched roof than if it has a flat roof. We have really embraced this rule. Designers in Toronto have placed restrictions on themselves concerning what represents “newness” and what is “modern,” creating an ideological hang up. There is so much modern European work that has embraced typologies of gabled roofs unapologetically. We found a very interesting territory to stake in walk-up typologies, using pitched roofs and volume in spaces that traditionally were attics. In thinking about volumetric considerations, we’re really embracing this typology by putting some of the main spaces, such as the kitchen and living rooms, up on the second and, particularly, third floors. The Galley House, a very narrow house in Toronto, has a radical presence on the street because the most visible portion of the house pushes forward as a double-height living room elevated on the second floor.

DC: There’s a de facto response of modernist architecture to have a flat roof, where I think we approach some spaces and volumes with the attitude that a pitched or gabled roof might be the right solution and can still be a modern design. Why would we ever question some of the most basic and beautiful principles of, for example, shedding water by gravity? We don’t see limitation in these forms that some may call too “traditional” looking; we see opportunity.

Abbey Gardens | Rendering courtesy of Williamson Chong Architects

Abbey Gardens | Image courtesy of Williamson Chong Architects

AR: Your community master plan for the 441-acre Abbey Gardens site represents an expanded scale for your work. What was the genesis of this project, and what has your role been in programming the site?

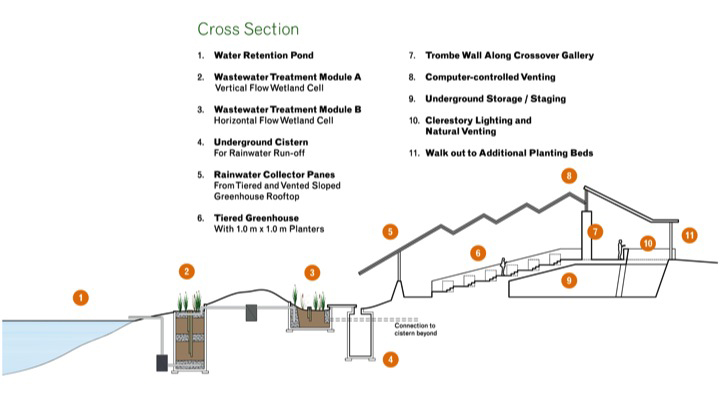

BW: We began working on Abbey Gardens in 2009 or 2010. A community trust was developed by a group of like-minded people in Haliburton County, in Ontario, with the goal of creating a space that addresses holistic living, growing healthy food, and bridging the relationship that people in urban centers and agrarian centers have to food.

SW: We are the catalysts and stewards of the project. We are willing Abbey Gardens into existence because we’re tremendously excited by it. When we met John Patterson, the founder of the community trust, he saw that we could help craft this former quarry site he was interested in turning into a farmers market into something of a hub for conversations and exchange. It’s taking an artists-in-residence approach, where a range of people along with experts — whether a nutritionist or a food security expert or someone like Michael Pollan — can come together and connect. They felt that was a good civic underlay, not unlike the market agora that started in cities long ago.

DC: The trust engaged us as the architects a lot sooner than they probably should have, in a traditional sense, but they found us able to really spark conversation and so we were rolled into the program development very early on. Rather than provide a prescriptive master plan, we can engage with this diverse user group and tailor the program to user needs. We actually now think that this is an intelligent model, because if we hadn’t been involved in that way and had just been waiting by the phone, I don’t think they would have purchased the land. As Shane was saying, there’s a balance between pushing and cradling, and we hope that we’re adept at nurturing the fragility of what we see is a promising idea.

Door with Peephole | Image courtesy of Williamson Chong Architects

AR: Tell us about the work you’re doing in relationship with your recent Professional Prix de Rome from the Canada Council of the Arts. What is your interest in advanced digital technology, particularly as it relates to wood?

SW: We were awarded the Prix de Rome to research emerging wood technologies and to study the use of digitally fabricated construction, which we’ve been looking at on the scale of furniture and millwork for years. We see fantastic opportunity in deploying emerging wood technologies such as Cross Laminated Timber at a larger scale. CLT is very much still a novelty in America, whereas there’s far less novelty associated with it in Europe.

BW: To illustrate Shane’s point: there was a real estate start-up that approached us with a very skinny urban site for a five-story building with a fairly small budget. Because of our research, we proposed a structural wood project made from Cross Laminated Timber. Our pitch was that as the first wood mid-rise structure in Toronto, the young firm would get a lot of press and could emphasize their ecological mindset. We saw this innovation as mutually beneficial, and proposed the project as a showcase. We didn’t get the project; they wanted more conventional construction. So sometimes when potential clients or projects come to us we take a fairly decisive stand on the direction. If the fit is good, the project really sings. If the fit isn’t good, we don’t sweat it because we know that the relationships between the client, the contractor, and the architect are so important and you’re not going to be able to force it.

SW: We see our experience and interest in the parametric underpinnings associated with fabrication, particularly in a Canadian context, as something we can exploit in wood technologies. We’re testing the waters for positioning CLT as a replacement for concrete. The Prix de Rome gives us an opportunity to visit Scandinavia, Austria, Switzerland, Japan, and Korea to understand the emerging typologies associated with these new technologies and to meet leaders in the field.

House in Frogs Hollow | Photo by Bob Gundu

BW: Fabrication is the first of three prongs of our research. I’d say the second is a challenge of innovation in Canada. While we have more wood, more natural resources than just about anybody, we don’t have the added value of innovation. So we’re looking to what a similar biome in Scandinavia is doing with their natural resource, and then looking at the innovation that countries like Germany and Austria have in spades — how can we marry those two things together?

The third prong is cultural. Like the United States, Canada has a fairly young cultural history. Europe, and Scandinavia in particular, has a much deeper natural ease with contemporary objects, contemporary work. In Canada, when people think wood they think rustic, like the knotty pine up at the cottage, not something that’s sophisticated. Part of our work is to talk to leaders in the industry, both in fabrication and in design, so that people in Canada will look at wood and think it’s an elegant, sophisticated material.

DC: That goes back to the fundamental idea of our voice and our drive to be proactive in this practice. We love to do the wood things, yes, but I will say it’s because we need to do it. We can be the catalysts, with the supporting research, to say that you don’t need to wait for the market to catch up or to determine that something is good. We think it’s incumbent upon us to try things out early; that’s our role as a research-based office that still builds and is willing to carry it through.

***

Donald Chong, Betsy Williamson, and Shane Williamson, Williamson Chong Architects, Emerging Voices 2014, complete lecture video | Recorded March 20, 2014 | Running time: 51:57

***

Both Shane and Betsy Williamson received their M.Arch. degrees from Harvard University. Donald Chong received his B.Arch. from the University of Toronto. All three have taught at schools of architecture in Canada and abroad, including the University of Toronto, where Shane Williamson is currently an associate professor and Betsy Williamson a lecturer. Recent recognition for the firm includes the Professional Prix de Rome from the Canada Council for the Arts, the IDS 212 Gold Award, a Canadian Architect Award of Excellence, and an Ontario Association of Architects Design Excellence Award, one of many for the House in Frogs Hollow.