Unflattening the strip mall

SCHAUM/SHIEH develops strategies for contributing to the civic realm in environments very different from the Italian hill towns they studied in architecture school.

SCHAUM/SHIEH is a 2019 Emerging Voice.

By Sarah Wesseler

SCHAUM/SHIEH has received commissions that most young architecture practices dream of, including art galleries and Venice Biennale installations. But partners Troy Schaum and Rosalyne Shieh also take on projects not typically associated with high design—they’ve worked on several strip malls, for instance.

In deciding whether or not to accept a commission, one of their top considerations is the client’s interest in the civic realm. The prestige of the building type—its location on the design world’s sacred-to-profane spectrum—is less important than the potential to contribute meaningfully to the urban fabric.

But it can be difficult to know what this means in contemporary cities. “I think if you trained as an architect in a certain generation, you have an ambition to participate in or respect the civic realm, but the civic realms we study come out of primarily walkable Italian hill towns and European cities,” Schaum said. Today, “most architects around the world are left confronting these spaces that don’t have that neat, legible, walkable urban form.”

This is the case in much of the United States, of course. Most Americans live in the suburbs, which are growing faster than urban and rural districts alike. And while New Urbanists and other designers have worked to inject architectural expertise into these environments, suburban construction is still largely driven by developers’ financial priorities and car-centric urban planning frameworks.

Schaum and Shieh both grew up in the suburbs and are interested in the complex, somewhat ambiguous urban condition they represent, where the richness of human life plays out in environments optimized for automotive infrastructure. “What happens if you think about a [project] site as the center of a larger territory which is this megalopolitan city dominated by asphalt parking lots and roads where nobody walks?” Shieh said.

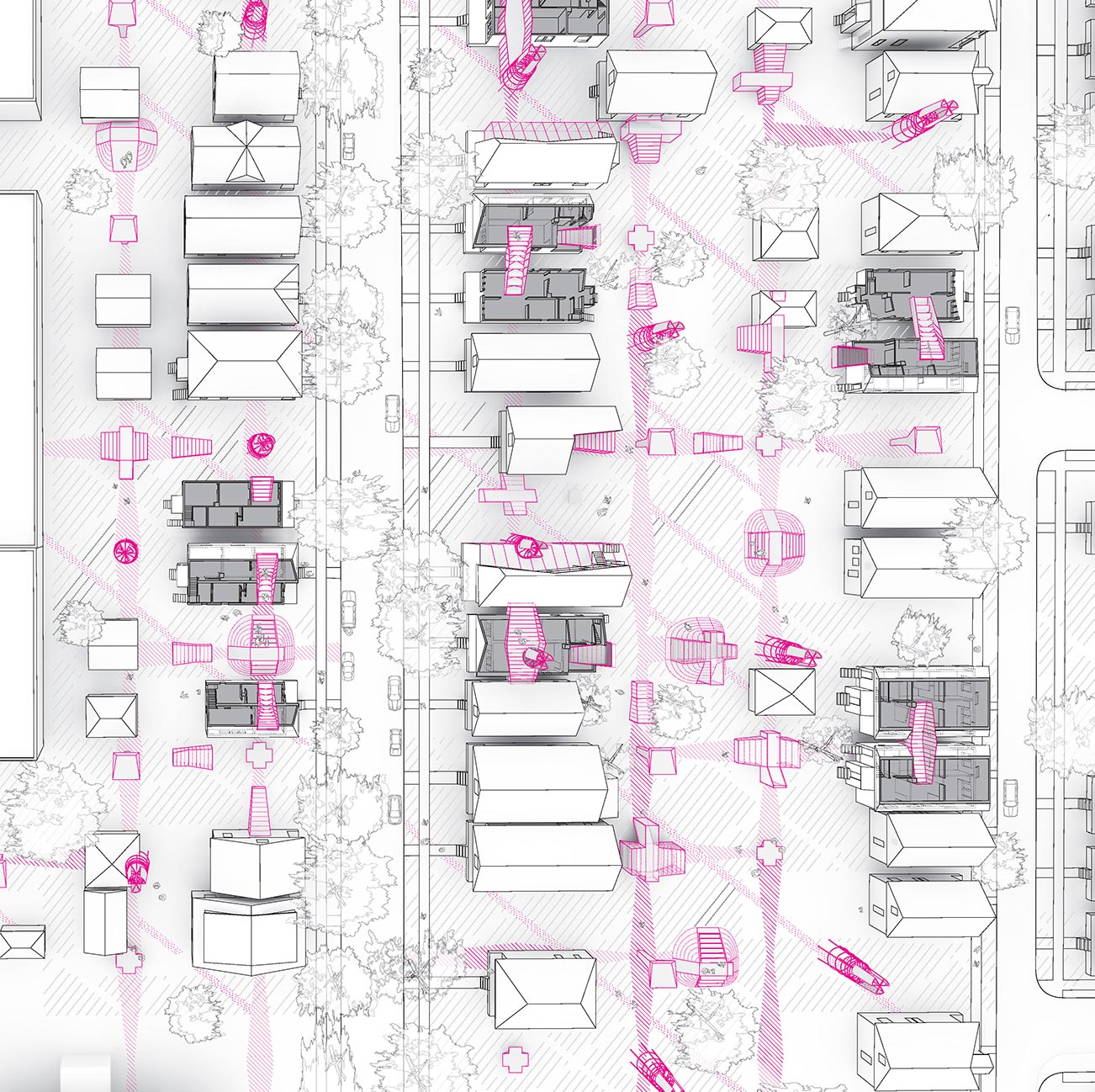

One of SCHAUM/SHIEH’s earliest projects, a speculative plan for a Detroit neighborhood struggling with abandoned properties, played an important role in advancing the firm’s ideas about the relationship between individual structures and the surrounding community. It proposed inserting small-scale infrastructure—bike sheds, informal stages, and the like—into open areas (backyards as well as empty lots), with the aim of facilitating multidimensional flows of movement and activity throughout the district. By encouraging new circulation patterns, Schaum and Shieh hoped to create serendipitous encounters, reframing empty space as an opportunity rather than a liability. They also proposed drawing upon existing infrastructure such as drainage and water pipes to support gardens.

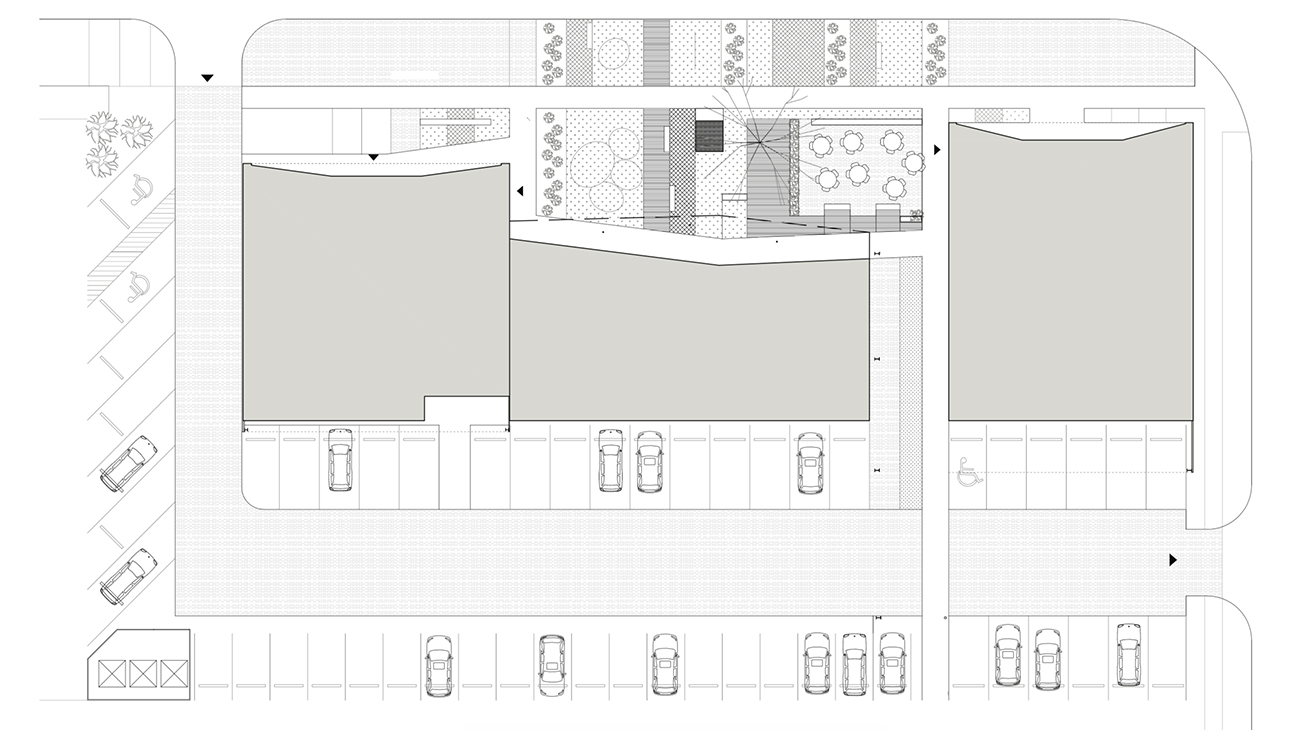

The firm employed a variation of these ideas for its most recent strip mall project in Houston, where Schaum lives. (Shieh lives in Brooklyn; their office is located in Manhattan.) Instead of focusing primarily on the elevation facing the road, as is typical for this building type, the designers worked to create aesthetic appeal on all four sides, as well to as encourage different ways of moving in and around the structure.

“People understand when they visit these places that there’s a kind of conceptual flattening, and often an actual physical flattening,” Schaum said. “We push back a bit and say, can we find space to expand that flatness?”

In the finished building, the parking lot sits behind the building and landscaping creates what the partners refer to as a “front stoop” facing the road. An outdoor walkway between two of the storefronts invites visitors to use different routes when moving through the development.

Meanwhile, a contoured roof and a wood-and-steel palette differentiates the strip mall from its neighbors without seeming to cry out for attention. “We tried to inject a few moments of material simplicity in a manner that matches the attenuated atmosphere of Houston,” Shieh wrote in an email.

Modest as they seem, these design moves were a significant achievement given the strong financial and regulatory currents that encourage cookie-cutter buildings in the area, according to Schaum.

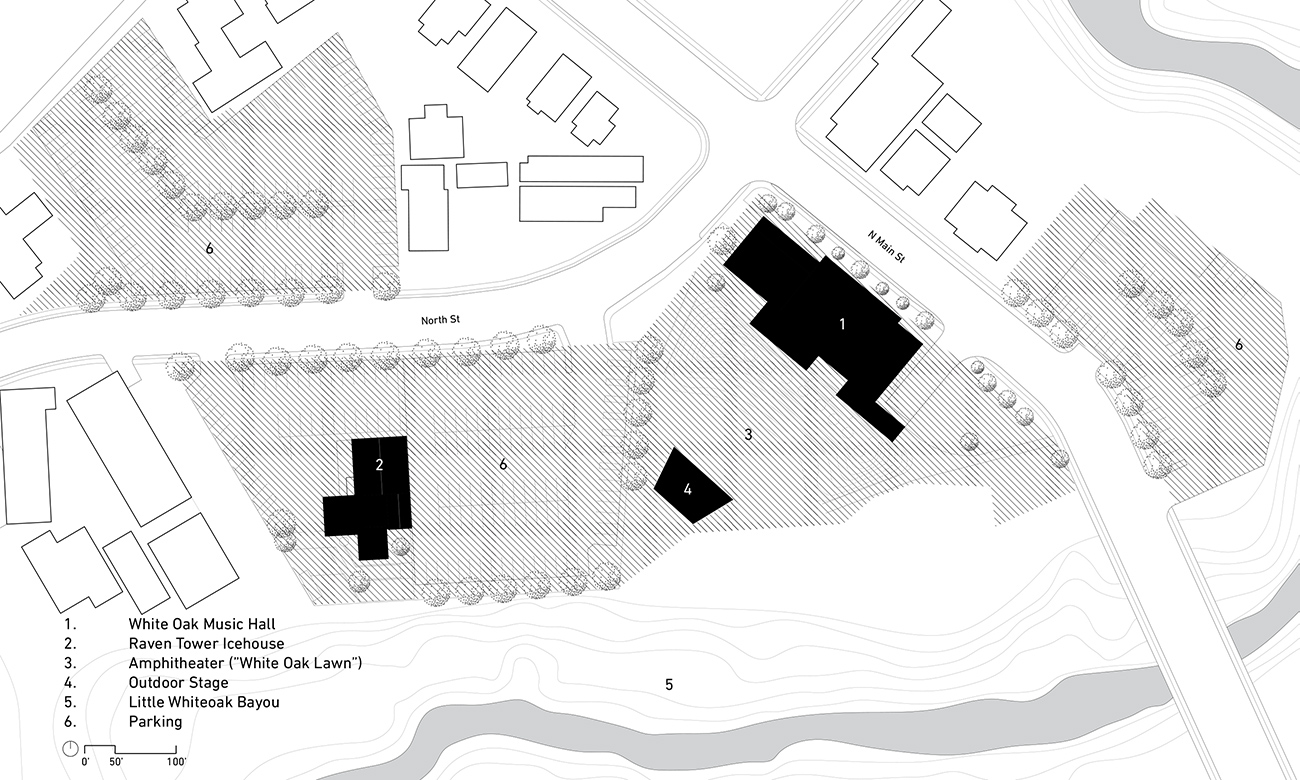

Another project nearby provided the first large-scale test of the firm’s ideas about suburban urbanism. The clients, a group of young music lovers dissatisfied with Houston’s live music venues, wanted to create a state-of-the-art performance center featuring both indoor and outdoor stages. Their site, located in a low-rise district next to the Little White Oak Bayou, was close to a light rail line and offered views of the downtown skyline.

One potential model for a cultural campus in environments like this is the lifestyle center, a development type that has become popular across the US. Often featuring new, multistory, vaguely European-looking buildings surrounded by parking lots, lifestyle centers encourage people to get out of their cars and walk in interior streets, but not beyond, creating what Shieh described as “a fortress-like island in the urban fabric.”

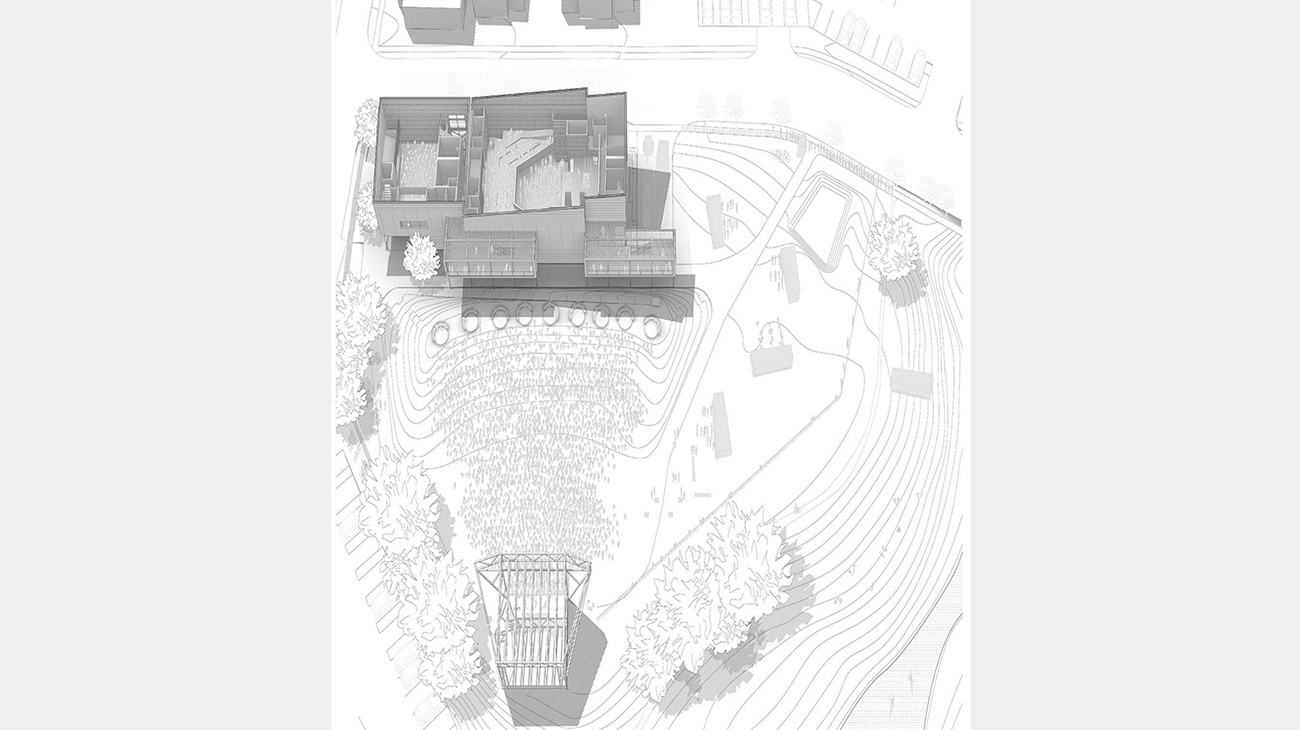

The finished White Oak Music Hall campus demonstrates an alternative to this model. SCHAUM/SHIEH wove together new and existing buildings and created thoughtful sightlines and circulation paths between them (and across two existing roads), giving the development a cohesive identity while linking it to the local context and history.

A former warehouse became an open-air venue for events and performances, while an adjacent tower (built by a metalworker as a “conversation piece” in the 1970s) was turned into an elevated bar. SCHAUM/SHIEH cut holes in the warehouse’s façade to give it a distinctive, contemporary appearance while keeping costs to a minimum.

The campus’s main venue, a new building with two indoor stages, features a roof deck and terraces offering views of the outdoor amphitheater and city skyline, as well as visual connections to the converted warehouse and tower.

For Shieh, much of the interest in projects like these lies in the opportunity to improve physical and social connectivity in suburban environments without resorting to stereotypes about ideal urban conditions.

“Why do the suburbs have to be more like Rome?” she said.

Explore

Maurice Cox lecture

Detroit's director of planning and development offers insight into the city's revitalization efforts.

Flash and spectacle in the face of austerity

Debroit-based Anya Sirota discusses the relationship between architecture, culture, and urban vitality.

Can rural black churches survive sprawl?

Long a vital community resource in the South, African American churches face growing threats. Cadaster believes designers can help.