The Road to Equity

For Kounkuey Design Initiative, transportation planning projects are one way to improve the built environment for everyone.

July 13, 2021

California's Eastern Coachella Valley suffers from a lack of transportation infrastructure. Credit: Kounkuey Design Initiative

In the Coachella Valley, an annual music festival and luxury resorts draw visitors from around the world. But tourists rarely venture to the eastern half of the valley, whose inhabitants—many of them immigrants—often struggle to get by in low-paying jobs.

Kounkuey Design Initiative (KDI), an interdisciplinary nonprofit with a global footprint, has spent years working in the Eastern Coachella Valley as part of its efforts to shape equitable communities through participatory design, planning, and research. Over time, its work there has evolved from relatively traditional public space interventions (e.g., park design) to a large-scale rethinking of transportation infrastructure—the kind of project typically viewed as the domain of technical specialists.

The League’s Sarah Wesseler spoke with cofounder and executive director Chelina Odbert about KDI’s transportation initiatives in Coachella Valley and its Southern California neighbor, Los Angeles.

*

How did your transportation planning work in the Eastern Coachella Valley come about?

We started to work in the area about a decade ago because we’d been asked by local community groups to help create public spaces, parks. But as we do with any project, we first took a zoomed-out approach to understanding the community and the political, social, and environmental landscape. We started by asking residents what they love about the Coachella Valley, but also what are the big challenges, how do those affect them, and how would they prioritize solutions.

What we heard was that the needs were varied and intersectional. Yes, residents needed and wanted public spaces. They needed safe places for their kids to play; they needed places to gather; they needed places for educational and extracurricular opportunities, for local exchange and commerce. Public space was a vehicle to address a lot of those needs.

But there were also several other major needs, one of which was transportation. The communities are very spread out and rural in nature, and most households have just one car, which is usually tied up by the breadwinner. We heard people say, “We want public spaces, but without more ways to get around, we aren’t going to be able to get to those public spaces easily to take full advantage of what they have to offer.”

From day one, we knew that transportation was a huge priority for residents. We didn’t have capacity to take on that issue immediately, but we filed the idea away to come back to.

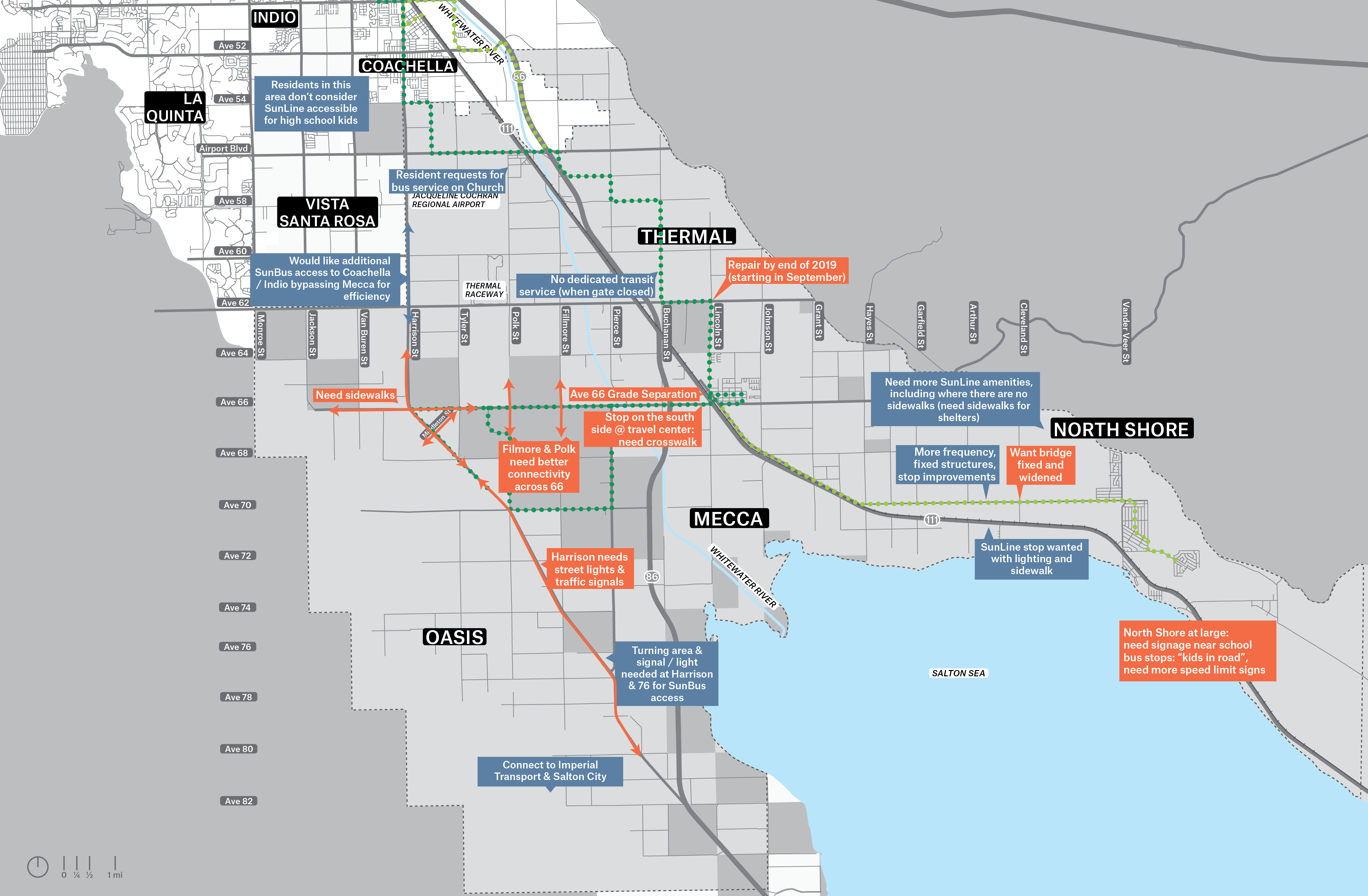

A few years into working on public spaces in the region, we joined a coalition of nonprofits that was working on transportation access. When we looked into the local situation, what we found was perplexing—the Eastern Coachella Valley and the Western Coachella Valley are managed by the same transportation department because they are part of the same county. But on one side of its jurisdiction, the department was able to provide rich and layered transportation infrastructure, whereas on the other side, it was not just less robust, it was truly nonexistent: no sidewalks, no bike paths, no street lighting.

We also learned that there’s a large pot of state implementation money that’s accessed through a competitive application process, but to apply for those dollars, communities need to have a county-approved mobility plan—essentially, a long-range planning document that physically and narratively maps out an ideal, fully built-out, multi-modal transportation network for the region. But none of the communities in the Eastern Coachella Valley, which are small and unincorporated, had such a plan. So we, with some other partners, got buy-in from the county and applied for funding to lead these planning processes on their behalf.

Typically, those plans are very wonky, done in a closed room with a few transportation planners and a lot of GIS. We said, what if we open up the process, share the decision-making power—as we do in all of our designs—and ask residents what needs to be connected and in what order?

The funding was awarded, so we started to develop the participatory transportation planning process, which we carried out with residents in two communities. From that we wrote the plan which was then adopted by the County. And while momentum was strong, we said, “Let’s not stop now. Let’s immediately roll this into an application for funding to pay for implementation of the first 14 miles of the plan.” So we did, and we won funding. That first phase is in a lengthy procurement process at the moment.

With the success of that process, the county transportation department said, “There are more communities in the Eastern Coachella Valley that need this.” So we created a second plan that covers the neighboring two communities, and then a regional plan that basically covers the entire east side of the valley and shows connections beyond. Those plans have also gone through the community design process. They were adopted by the county and will hopefully be funded as well.

So as you said, this project relates to your larger practice in the sense that you took a holistic view of the community’s needs and worked closely with it to create solutions.

Absolutely. We could have just gone in a room and made the transportation plans, but what is clear after the fact is that, had we done this, we would have gotten it wrong in some big ways.

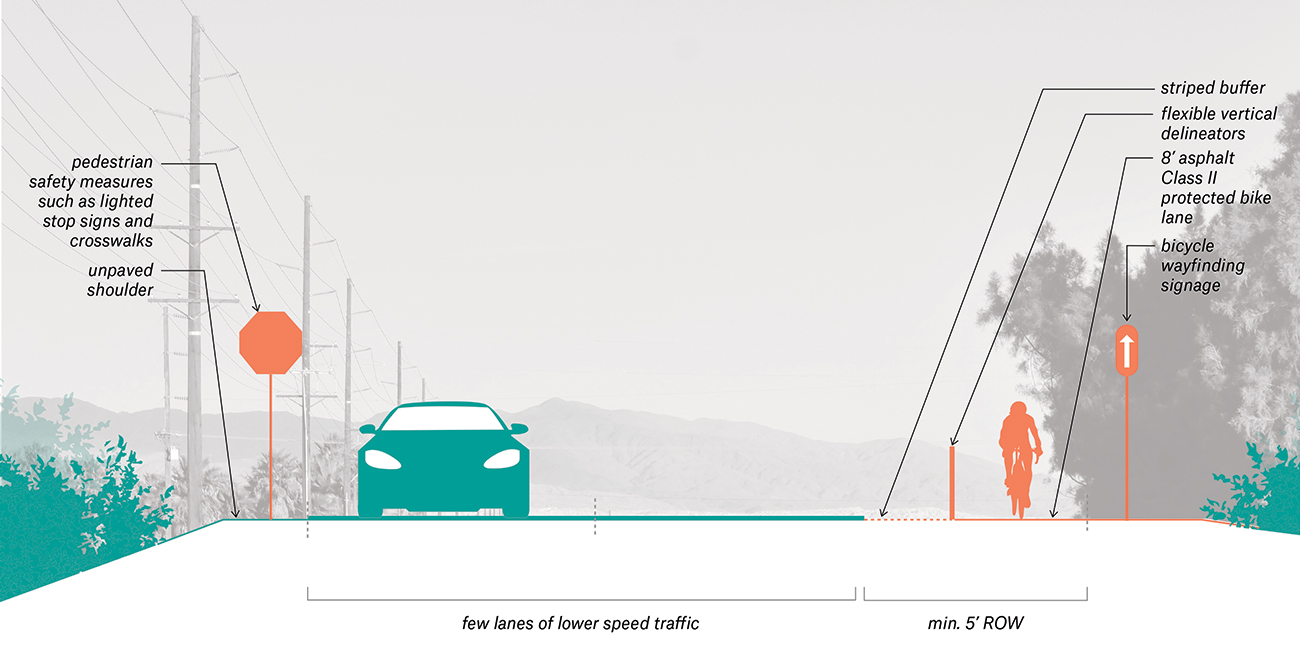

One example is sidewalks. Our transportation plan doesn’t have sidewalks in the traditional sense—as you might find them in the Western Coachella Valley. This is a more rural setting; roads are wide, and they trail off into shoulders that trail off into empty fields. There’s not a lot of distinction in the ground plane. Through our design process, it became clear that the idea of a sidewalk was very scary to residents. They didn’t want to be that close to these country roads where people in vehicles are speeding by.

Instead, we ended up with a set of pathways set off from the road. There’s a big buffer between them; they’re much wider than sidewalks, so they can accommodate caregivers who are walking with strollers or children or elderly family members. It’s just a whole different type of transportation infrastructure and streetscape design because these plans came out of this community-engaged process.

Is that typology something that the county transportation department recognized and approved right away, or did that require a lot of negotiation?

We did get asked, “But, wait, where’s the sidewalk?” You have to start looking at very technical engineering and safety guidelines and say, what does it mean to not have a sidewalk but still guarantee safety? So we did have to take the community’s expressed intent and interpret that in a way that also met the design criteria, guidelines, and expectations of the department that would ultimately be responsible for developing, constructing, and maintaining this infrastructure.

You’ve also worked on transportation projects in Los Angeles. What have those involved, and how do you see them fitting into your practice as a whole?

In general, KDI is driven by a goal of creating a more inclusive public realm. For us, that means a public realm that is just, complete, and resilient. When you look at our work from that level, it begins to make sense why we have these very technical transportation planning projects paired with designs for public parks paired with very large-scale environmental justice campaigns. All those things are levers for getting to that inclusive public realm. Sometimes it’s as straightforward as designing and building the things that are missing, but sometimes you can’t do that before you change policy, and sometimes you can’t change your policy before you’ve changed your mindset. Our projects move throughout all those scales.

One thing we focus on within that broader goal of creating an inclusive public realm is asking who is left out of the public realm. As we know, the built environment is not neutral, and typically public space isn’t truly public to all publics. So who are the groups that are left out of a park, or who don’t feel safe on a street? When we start to ask that question, we find that this applies to many groups. In fact, more groups feel excluded than feel included.

We look at this across race, income, etc., but we also use the lens of gender. We’ve been looking at what it means for the public realm to be gender-inclusive for a long time. We explored this on a global scale for the World Bank, writing its Handbook for Gender-Inclusive Urban Planning and Design.

The Department of Transportation in Los Angeles, which has also begun to think about this issue, commissioned us to take on this question of how transit works or doesn’t work for women and gender and sexual minorities in the city of Los Angeles. This is another fundamental part of our practice: research and data. Until communities can accurately define the problems, after all, solutions will miss the mark.

So we designed a participatory study of the transportation system in LA, specifically looking at gender. Essentially, it was a layered process that looked at existing data and information but also collected a lot of new data through a wide survey across three study neighborhoods, and then also through a more in-depth study tracking travel diaries and patterns of individual women.

Through that study, we quantified a lot of things that we already suspected were happening, but we did it in a way that allowed the City to understand them better. And from there we’ve created a set of recommendations: some that are about the department’s operations, some that are about the design of physical spaces, some that relate to the services the department provides, and some that are about policy—the larger levers that need to move before some of the more specific changes can really have an impact.

After the report is published, the idea is the City could begin to pilot some of these solutions.

What were some of the solutions you proposed?

One of the biggest findings is that there’s a duality to the question of gender equity and transportation that’s really driven by race and income.

For example, because of the caregiving responsibilities typically assigned to women, public transit often presents a much higher economic burden than it does for men, because women need to take multiple trips and pay multiple fares—LA doesn’t have a one-pass-for-all system. But women with a certain economic status are not affected by that burden in the same way.

One of the big takeaways was that even within this group that is less served by transit, there’s a subgroup that’s even more burdened by the system. A lot of the recommendations start at that high level, saying that solutions need to prioritize the needs of low-income women of color.

To me, it seems like transportation is basically a disaster in the United States in general, which is one reason I thought it would be interesting to discuss this aspect of your practice. I’m wondering to what extent you think your involvement with this issue could be instructive to other architects who want to make the built environment better and more equitable? And following from this, to what extent do you think your findings in the Coachella Valley and LA are generalizable to other American cities?

Starting with the second question, I think they are 100 percent generalizable. And to your point about the US being a disaster when it comes to transportation, in all the work we’ve been doing on this issue, we’ve seen that over and over. For example, the LA study is very novel for the US; transit systems don’t tend to include this layer of information. But in a lot of other places in the world, this is old news and they’re already on to fixing the problem.

All the cities that come to mind when you think about good transportation—Amsterdam, other cities in Europe—essentially, what we’re doing in the Eastern Coachella Valley is trying to propose very, very simplified versions of the really comprehensive multimodal networks they offer: walking, biking, public transit. They’re the gold standard.

Some architects obviously work on transit-oriented development, and some large firms have in-house transportation planners. But it seems relatively rare for architects, landscape architects, etc., to take on transportation projects as such. What do you think architects can bring to the table for these kinds of initiatives? Why is it beneficial to have them involved?

Well, I definitely want to acknowledge that transportation planners are the foundational players within transportation reform and innovation. But they can be greatly aided by other disciplines within the design profession—architecture, landscape architecture, urban planning—because those disciplines are able to put these questions in context with the rest of the built environment. And when you do that, problems usually become a lot more complex, but that complexity also drives innovation. It drives solutions that are better able to address the full scope of the problem.

For example, we recently participated in a project where the City of LA asked firms to take on the question of shade equity at bus stops. In large portions of the city, bus stops aren’t shaded, and this happens largely in low-income communities of color. Of course, transportation planners and engineers can provide shade at bus stops; that’s what they do. But the question of shade at bus stops is related to 100 other questions of equity in the public realm, or even just urban design. So when you bring architects and landscape architects into the conversation, you end up being able to address multiple issues with something that’s generally considered just a transportation problem.

The way I think about KDI’s work in this area is that we started by talking about public space, and over time we’ve realized that what we’re interested in isn’t just public space—it’s the public realm. In the Coachella Valley example, the need wasn’t just public space; it was also a need for connective tissue. You can’t work on one without thinking about the other. The more we worked on public space, the more we understood that the catalyst for equity is really the entire public realm.

And today, the public realm is the barrier to equity. There’s a growing body of research about how life expectancy is determined by zip code. When you look at what’s driving this, it’s elements of the public realm: safety on the streets, freedom from environmental hazard where you live, presence of social infrastructure like parks and cultural centers, etc. As this research shows, those elements of the built environment are not just design flourishes—they can determine whether people live plus or minus 15 years. In this way, we are confirming the hypothesis that led us to launch KDI in the first place: that addressing inequities in the built environment can lead to healthier, fairer, and more just lives.

Interview condensed and edited.

Explore

Personal mobility

Experts explore the links between urban transportation systems and climate change.

Bruce Schaller on transportation in New York City

A noted transportation consultant discusses the mobility challenges and opportunities facing the city.

November 3, 2018

Ground transportation and climate change

A one-day conference exploring the future of land-based transportation.