The cost of living

In 1987, the League collaborated with the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development to launch a design study on the potential of small-scale infill housing to contribute to the city’s affordable housing needs. The Vacant Lots project culminated in an exhibition and publication, portions of which are republished here on archleague.org.

In the following essay from the 1989 Vacant Lots publication, Rosalie Genevro reflects on the economics of affordable housing and highlights submissions that creatively address how to bridge the gap between the actual cost of providing housing and the ability to pay of people who need it.

Most simply put in economic terms, the housing problem derives from the gap between the income and ability to pay of people who need housing and the actual cost of providing it.

There are two basic ways to try to bridge this gap: either make the housing itself less expensive, or increase the ability to pay of those who will use it. Making the housing less expensive can be accomplished by using simple construction methods, lower cost materials, or simplified, repetitive forms, by employing low-cost or volunteer labor, or by reducing the cost of money borrowed to build. Or government can provide construction subsidies that acknowledge the high cost of building but reduce the cost to the final consumer of the housing.

Increasing the ability of tenants to pay can also be accomplished in several ways: through direct rent subsidies, either to the tenant or to the building owner; by grouping more individuals with more potential income into a space; or by indirectly subsidizing rent or mortgage payments, through interest subsidies on loans or tax subsidies that make mortgage interest deductible.

Paradoxically, government seems to have made the effort to address the housing shortage harder for itself by attempting to jump from the desperate to the ideal. Standards for subsidized housing design in New York City, as represented by HPD’s design guidelines, are high, perhaps higher than the norms to which so-called “luxury housing” is built by private developers. Many of the projects in the Vacant Lots study that directly address the issue of affordability do so by attempting to circumvent design guidelines, building code standards, setback requirements, zoning, or Floor Area Ratio regulations that seem excessive.

G. Phillip Smith/Douglas Thompson, Site 7

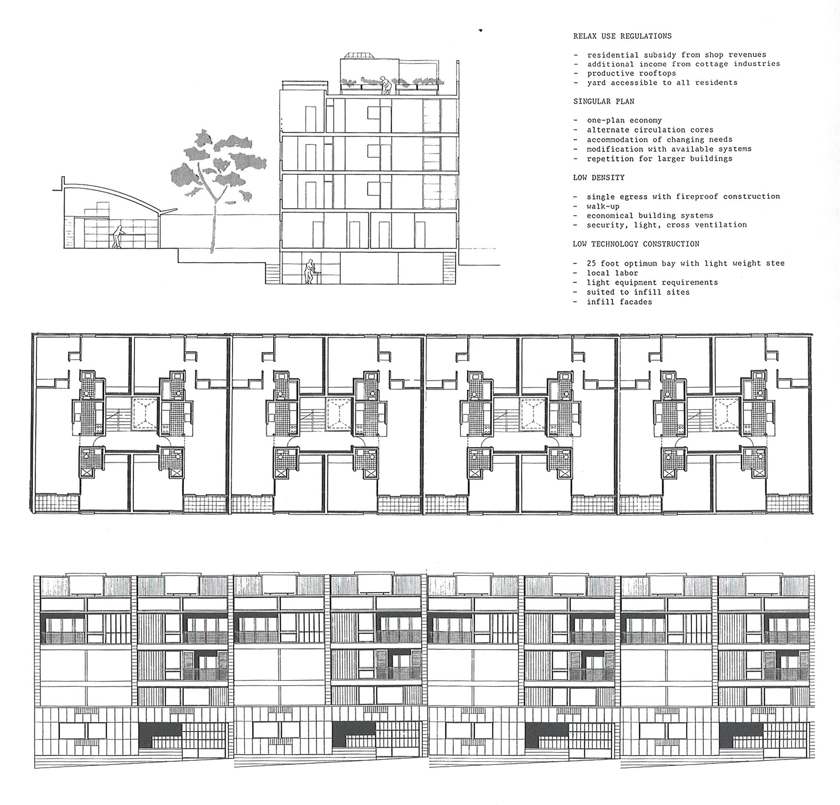

This approach is most apparent in the projects for Site 7 in Harlem. A project by Peter Samton, Gery Vasisko, and Bob Genchek of Gruzen Samton Steinglass proposes a building that would look at home on this street of six-story old and new law tenements, but which avoids the need for an elevator by maximizing site coverage rather than height and by making duplex apartments on the top floors. Smith and Thompson Architects propose a walkup building that does not build to the zoned limit, uses only standard size materials and one standard unit type, and requires only one means of egress because of its fireproof construction.

A project by the Samuel Haffey team for Site 7 makes a proposal to treat the public and private parts of the building as two separate entities, with the public part — the façade — to be built of durable and “public quality materials,” paid for and maintained by the city. The private areas of the building behind the façade are quite minimal, with no interior public space and with all tenants required to vacate every five years so new renters can have the advantage of the housing subsidy attached to the building.

Samuel A. Haffey Architects & Engineers, Site 7

Saunders/Heidel, working on Site 8, do not conform to the city’s side-yard setback requirement. They propose instead a kind of “zero lot line” design that, when repeated, would aggregate side-yard allowances to form larger, more usable areas accessible to tenants on both sides of the space.

Interestingly, no team proposes using prefabricated buildings, although several suggest the use of prefabricated elements within a “kit of parts” approach. John Cutsumpas on Site 1 and the William McDonough team on Site 10 both specify the use of prefabricated concrete panels.

Using the labor of the future tenants or owners of the housing to help in construction and thereby reduce costs is suggested by a number of the architects and designers. Because of the low density of the neighborhood and the simple forms of the surrounding houses, Site 9 in Jamaica, Queens seems to lend itself well to this idea. Both Mark De Marta and William Gati propose the use of “sweat equity” workers for their projects on Site 9.

The project for Site 2 by the Voorsanger and Mills team led by Bart Voorsanger takes a mixed approach, combining change of the physical form of the apartment with a new concept of ownership. To enable single and low-income individuals to benefit from the tax advantages and equity-building possibilities of home ownership, the Voorsanger scheme proposes creating large apartments comprised of jointly owned common spaces — kitchen and living areas — and individually owned sitting room, bedroom, and bathroom suites.

Other teams also broached the possibility of increasing rental income by designing for tenants other than conventional families. Several teams propose variations on congregate living situations that would take advantage of the economies of shared common space. Keith Strand, working on Site 1, proposes to combine market rate and subsidized units in the same building, to achieve economic integration and to effect a “cross-subsidy” of units within the building.

Few of the Vacant Lots projects were costed out to see if the assumptions made about the cost-saving potential of selected materials and techniques are borne out in the forbidding real world of New York City construction costs. The simple dignity of many of the designs, however, and their success in responding to their surroundings, does offer hope that new housing can be built that is humane, relatively economical, and aesthetically satisfying.