The Art of Running an Architecture Firm

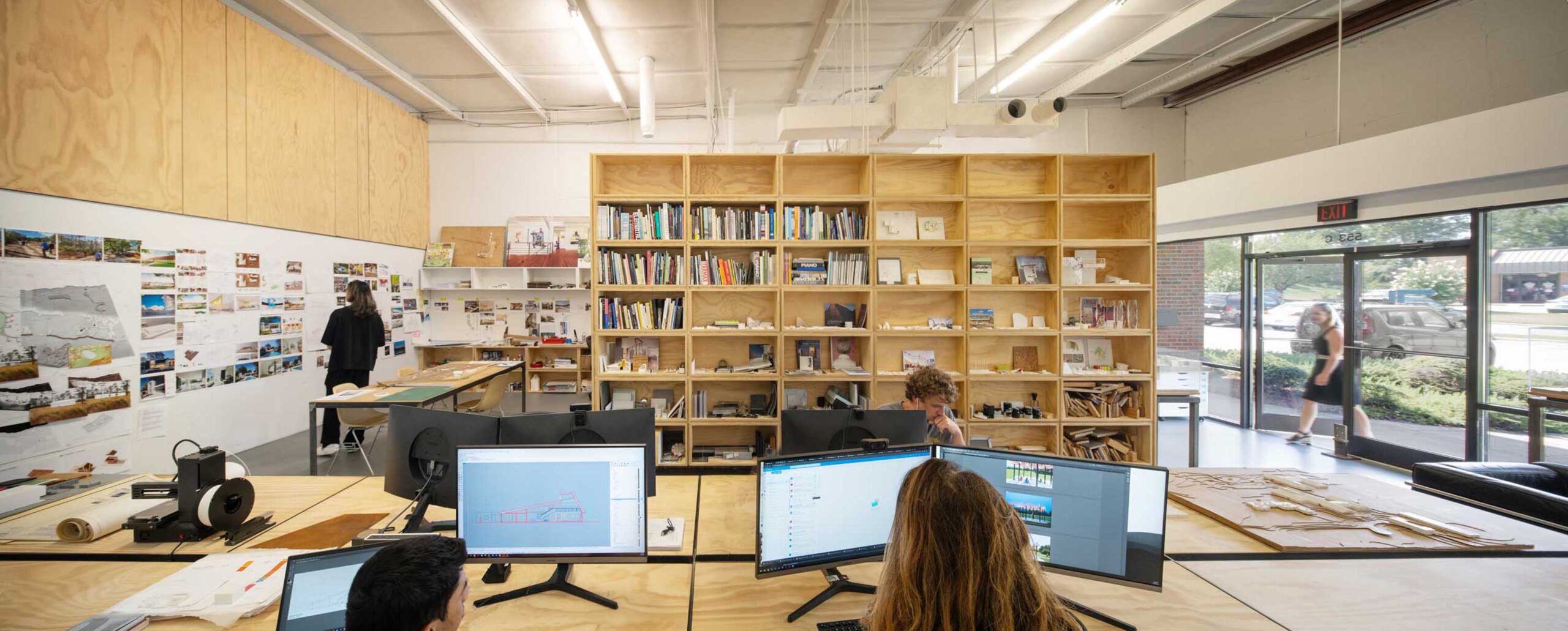

Katherine Hogan Architects has developed inventive tactics to thrive as a small practice and serve its Raleigh, North Carolina, community.

March 7, 2023

Lobby of Southeast Raleigh Magnet High School in Raleigh, North Carolina, after a renovation by Katherine Hogan Architects. Image credit: Tzu Chen Photography

Katherine Hogan Architects is a 2023 Emerging Voice.

By Sarah Wesseler

For 15 years, architect Katherine Hogan and architect/contractor Vinny Petrarca practiced together as Tonic Design/Tonic Construction, gaining a reputation in their Raleigh, North Carolina, community as a skilled design/build firm with a substantial portfolio of private homes. But when they tried to shift to a new focus on public work, they found that Tonic’s name recognition worked against them.

“We were being put in a box of ‘You only do one thing,’” Hogan said.

Hogan and Petrarca initially built their reputations with high-end residential projects while practicing as Tonic Design/Tonic Construction. Image credit: Mark Herboth Photography

When Hogan, who was particularly determined to do more institutional work, would try to set up meetings with potential clients, she found that many key stakeholders didn’t take her seriously, not understanding that she was a principal of the firm. “They were thinking, ‘Oh, you’re a project manager or marketing person or whatever,’” Petrarca said.

To get around these challenges, the firm rebranded in 2021, calling itself Katherine Hogan Architects. “Basically, in the middle of the night we just threw away our whole portfolio and our name and just started a different thing,” Petrarca said. “We knew it would work out, but it was kind of crazy, the transition.”

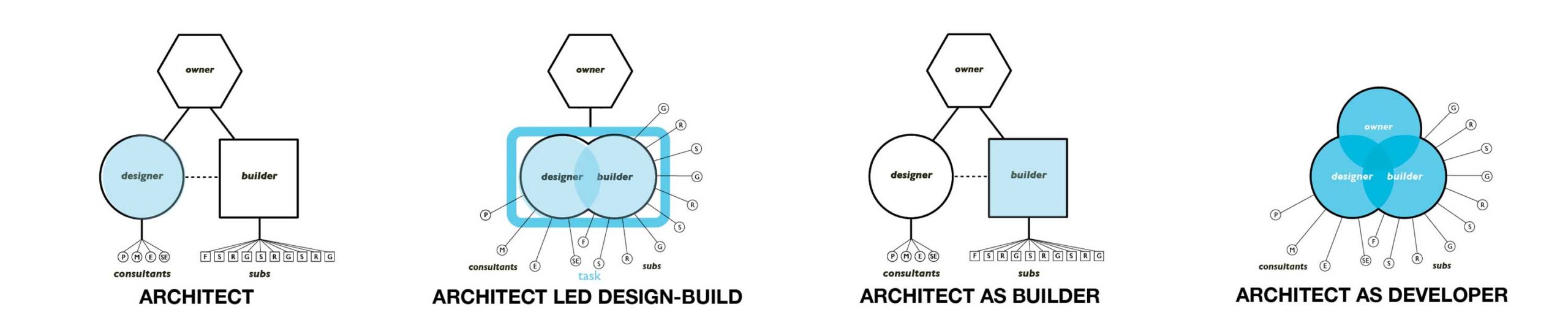

This rebranding is one example of the modest but inventive tactics the firm has developed over time to expand the services it offers and widen its network of clients and collaborators. Determined to thrive in the long term as a small, independent design firm—not an easy ask—and eager to be useful to its local community, the practice often foregrounds aspects of the architectural profession that typically operate out of the spotlight: namely, business development, project financing, and integration with construction.

This work is rooted in careful observation of the forces shaping the built environment in its region. Raleigh regularly appears on “best places to live” lists, thanks largely to the flourishing technology sector in its metropolitan area, which is better known as Research Triangle. (Nearby cities Chapel Hill and Durham form the other two points in the triangle.)

But with a population of approximately 2 million, Research Triangle doesn’t offer the same volume of design commissions as cities like New York or Los Angeles, and much of its new development consists of generic sprawl.

Moreover, access to high-quality architecture and infrastructure varies widely in the area. The strong tech job market and steady population growth haven’t benefited all residents equally, and socioeconomic divisions are clearly reflected in the built environment.

This local context has provided a roadmap for the firm’s activity over the years. “Understanding the systems beyond design—social, political, economic—I think is so important,” Hogan said.

During their Tonic days, the principals realized that typical financing structures put an architect-designed home out of reach for all but a tiny fraction of the local population, since they require cash in hand for two down payments: one for the architect (typically 10 percent of the total construction cost) and another for the bank loan. To reduce this upfront investment for clients, the firm set up a model in which it acts as both general contractor and architect, enabling clients to pay only 1 percent of the design fees upfront, with the rest being paid over time as part of the mortgage.

For another project—their own home—the married designers are investigating multigenerational residential typologies, with the goal of developing alternatives to standard suburban development models that exacerbate sprawl, car dependency, and social isolation.

But the trajectory of their practice is perhaps most clearly seen in their shift to public work, which has led to projects in K-12 schools, universities, and parks.

Hogan and Petrarca see this transition as more fulfilling, as it allows them to serve more people in the region. It’s also more sustainable from a business perspective, they believe, as institutional fee structures allow them to focus on fewer projects at a time.

Art as Shelter, a pavilion in the North Carolina Museum of Art Park in Raleigh, designed in collaboration with Mike Cindric. Image credit: Jim West Productions

This shift was by no means inevitable, however, the principals said. For example, finding opportunities to work with Wake County Public School System, the district serving the Raleigh area, took years of determined pursuit.

“We’ve both always been passionate about school projects, and I really wanted to take the firm in that direction. So we started applying for a lot of small annual contracts,” Hogan said. But with no prior experience with school design, they were repeatedly turned down. “There was a lot of, ‘Thank you for your submission, but no.’”

Eventually, however, they found an entry point to working with the district. “We got, like, a little study and inched up the ladder a little bit,” Petrarca said. “It took a long time to break into the work that we used to do in some of our other firms.”

In the past few years, the firm has completed two renovation projects that drew on its residential design/build experience to maximize the potential of small budgets in a district that manages 198 schools. “It’s not like private schools” in terms of capital spending, Petrarca said. “This is kind of like, ‘We’re trying to keep all the schools not leaking and open.’”

In one project, the brief was to transform a high school lobby from an unloved space devoted primarily to athletic trophies into a welcoming gathering space for students.

Southeast Raleigh Magnet High School high school lobby pre-renovation. Image credit: Katherine Hogan Architects

The school’s dynamic principal was the driving force behind the effort: Determined to help her students graduate and go to college, she wanted to offer a campus-like atmosphere to ease the transition to a university setting.

“These students spend so much time in the building, and they really didn’t have a place to sit,” Hogan said. Providing an attractive space to socialize and collaborate could help make the difference between “wanting to go to school versus not wanting to go to school,” she said. “I think that was really the intention of this project.”

After meeting with students and faculty to understand their needs, the firm developed inexpensive design interventions for the lobby. To brighten the space, they painted the walls white and created a dramatic light fixture using off-the-shelf LED strip lights—“what most people have underneath their kitchen counter,” Petrarca said—covered by steel elements fabricated in their own shop. (The construction side of their practice, which is legally required to be a separate business, is still operational.) Trophy cases turned into open niches with tables and benches, while budget-friendly maple plywood wrapped the stair to create additional seating.

For a second project, a 70,000-square-foot elementary school in a suburban area, the firm was asked to explore the feasibility of renovating a 1980s building that the district would have typically torn down and rebuilt—a practice that was increasingly being challenged on cost and environmental grounds.

With a $10 million budget and a strict mandate to leave existing walls intact, as well as complete all construction within a 6-month window, the firm made a number of ADA upgrades, added a sprinkler system, and repaired damaged slabs.

Before and after photo showing renovation of Raleigh's Brassfield Elementary School. Image credits: left, Katherine Hogan Architects; right, Tzu Chen Photography

To add aesthetic interest, it focused on existing skylights, building brightly colored new ceiling elements that draw in more natural light.

A unified color scheme of white walls with yellow, blue, and green accents helped give the illusion of a brand-new space.

“When kids and parents first came into the building, they were like, ‘This is totally a different project,’” Petrarca said.

The district considered the effort a success, the designers said, and it’s now being used as a model for updating similar buildings, resulting in significant cost savings compared to new construction.

The K-12 projects, like the firm’s other recent work with state parks and universities, have involved a substantial learning curve. In addition to working with a new building type, the designers have been required to absorb a significant volume of institutional standards and processes—and find creative ways of working within them.

“I think we’ve been able to especially have an impact within the county schools,” Hogan said. “They do value architecture and design, and our belief is that, given those constraints and those dollars, you still can have a big impact. And who better than for our students and children here—I think that if they’re in good environments, it just keeps perpetuating.”

Explore

Along the Lumbee River, North Carolina

Editors Morgan Augillard, Noran Sanford, and Joey Swerdlin present the report Along the Lumbee River with report contributors Tanner Capps, Deb Gunsallus, Ed Hunt, Ravin Patel, Christie Poteet, and Andie Rea.

Rekindling a Southern discourse

Architect Jennifer Bonner’s critical and conceptual practice attempts to redirect attention to the American South.

In conversation: Marlon Blackwell and Rick Joy

Blackwell and Joy reflect on first meeting 15 years ago, approaches to teaching, and a shared sensitivity to place while "transgressing the vernacular" in their work.