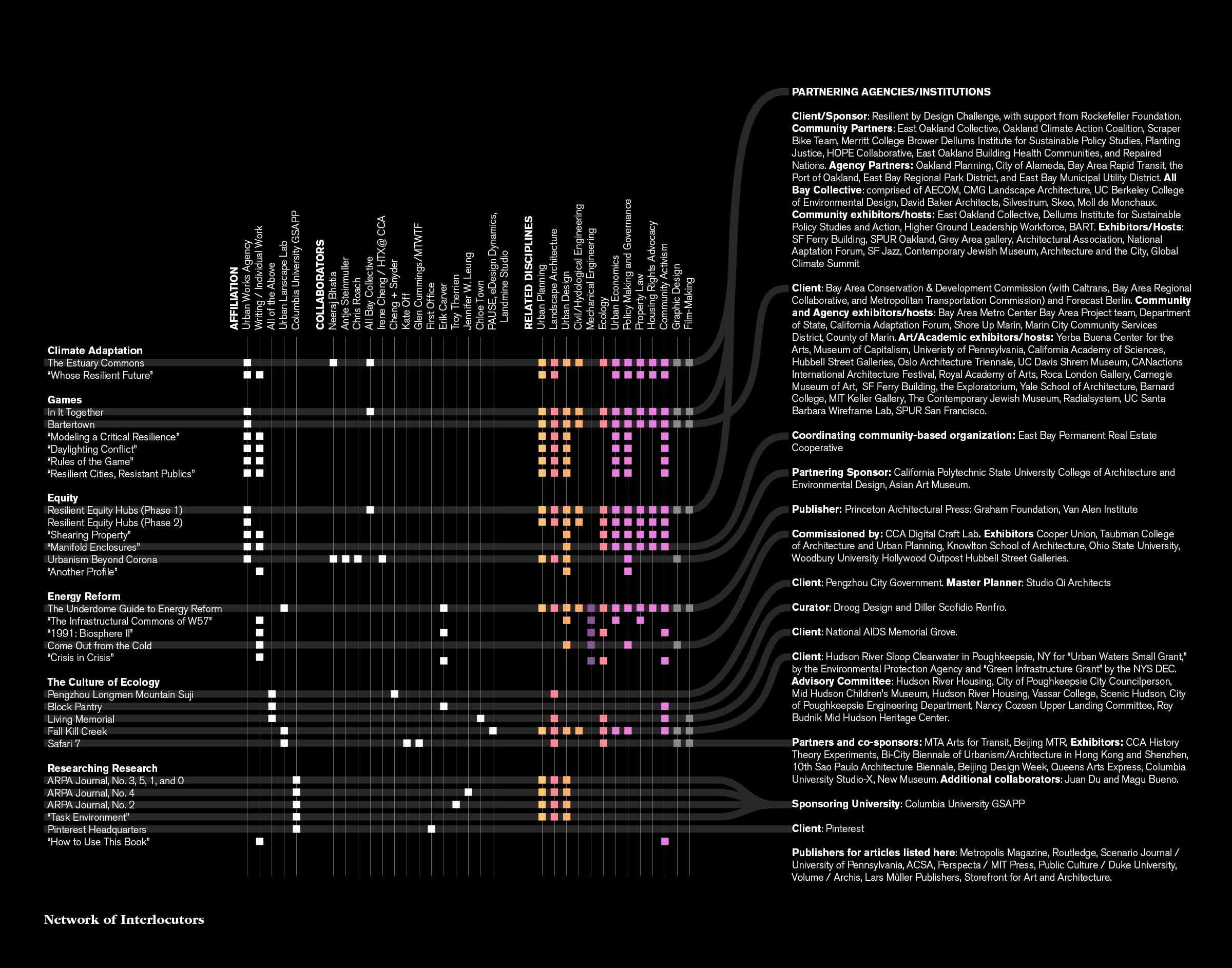

Team Player

For Janette Kim, wide-ranging collaborations provide opportunities to create a more equitable built environment.

March 21, 2023

Bartertown, a board game designed by Janette Kim (center), being played at the Oslo Architecture Triennale in Oslo, Norway, in 2019. Image credit: Istvan Virag

Janette Kim’s architectural practice takes a variety of forms, from designing buildings and publishing articles to co-directing a design research lab at the California College of the Arts. One through line connecting these activities is an interest in bringing different people and ideas together to create a more just society. She frequently serves as a translator between communities and disciplines, developing tools to guide collective decision making around complex issues like climate change and gentrification.

The League’s Sarah Wesseler spoke with Kim about her work.

*

Sarah Wesseler: We often take our cues from the Emerging Voices jurors in formulating these interviews, and they were particularly impressed by the sheer volume of collaborations in your work and the social impact they enable. When you first started practicing, did you know that you wanted to work in a collaborative way, or did that aspect of your work evolve over time?

Janette Kim: I don’t know that I set out to do that, deliberately. But after grad school, I wanted to understand how to work on political questions. One of the first projects I worked on, together with Chloe Town, was the design for the National AIDS Memorial in San Francisco. We won a design competition, which threw us into an extremely contentious two-year process in which people who were deeply involved in the AIDS Memorial debated amongst themselves whether our design was right for them.

I think that really laid this foundation for me of understanding the political process as one of debate. In this case, members of a very tight community were deliberating amongst themselves how they wanted to memorialize AIDS. I thought that was really exciting, actually, because people were so thoughtful about it, and I appreciated that our design sparked debate. And I think my excitement for collective deliberation really continued from there.

Wesseler: So viewing that firsthand made you interested in becoming involved in that sort of process yourself.

Kim: I think that’s right. And maybe I’ve always had a personality trait . . . I tend to be a mediator. So that situation felt almost familiar to me.

Wesseler: How did you find entry points into that kind of work as your career progressed?

Kim: The work I did on energy was probably the next major place where that idea of debate became important to me. I taught a studio at Columbia GSAPP where I asked the students to do mock debates around theories of nature. We even convinced members of the Columbia debate team to debate our projects for us. We talked about, for example, the difference between hippies and hunters, because they have somewhat overlapping value systems but very different politics.

So that sparked a recognition that with sustainability, or with energy issues, there’s no shared goal where we all know what’s right and what’s wrong. I got really excited about recognizing that it was, in fact, a contentious field in which we had to make political decisions.

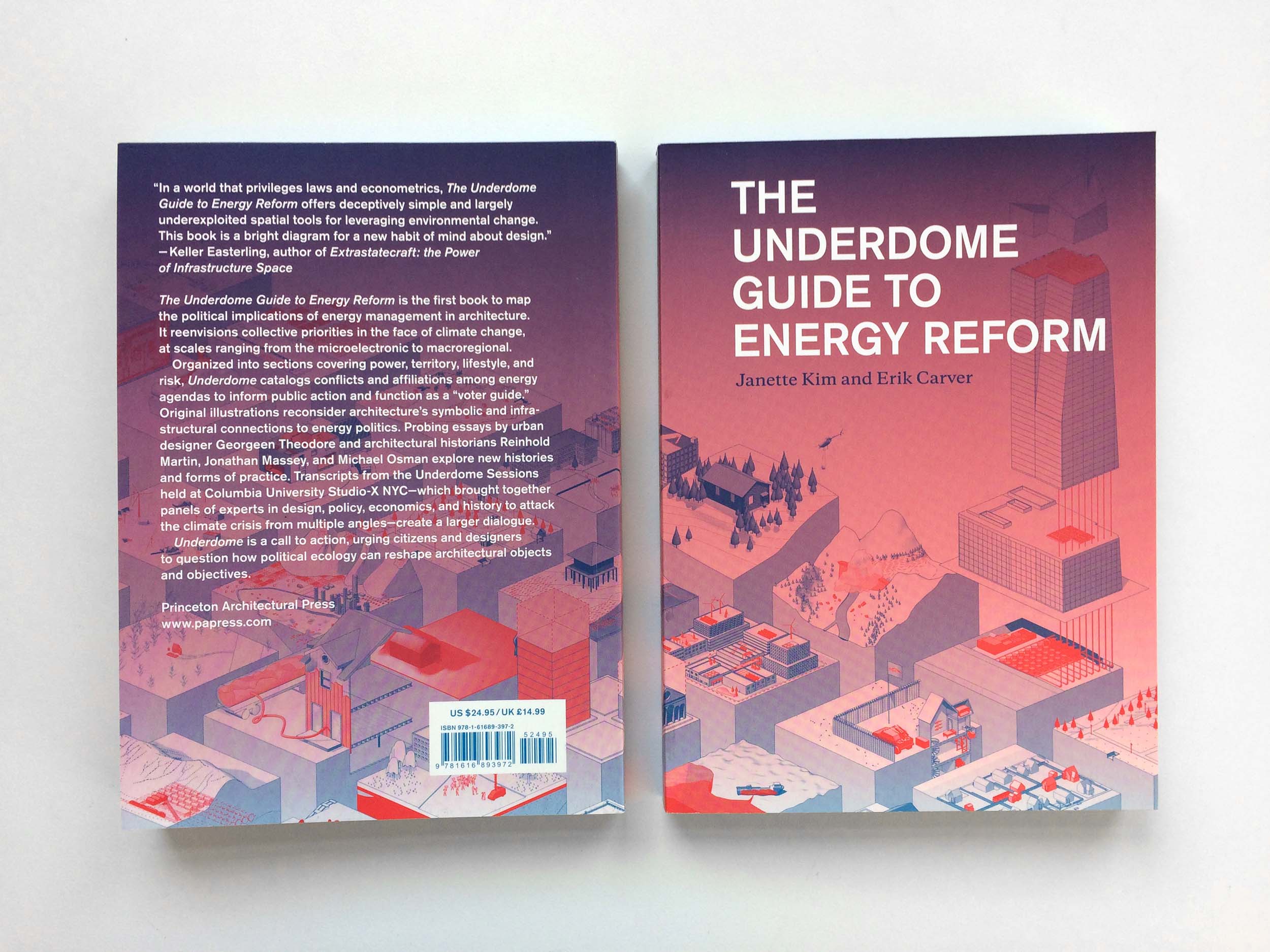

So later, when I wrote The Underdome Guide to Energy Reform with Erik Carver, we approached the book wanting to open up those debates—to emphasize that energy questions are not simply technical but require that people make choices about how to scale, define, and organize energy use around questions of equity and public responsibility.

The Underdome Guide to Energy Reform, published in 2015 by Princeton Architectural Press. Image courtesy Janette Kim and Erik Carver

Wesseler: The San Francisco Bay Resilient by Design Challenge seems like the most obvious example of collaboration in your portfolio, since there was such a massive group of partners and stakeholders. I imagine that determining what collaboration even looks like in that context would be a significant design challenge in its own right. I don’t know if that was part of your scope for that project, but could you talk about this idea of how you organize collaboration?

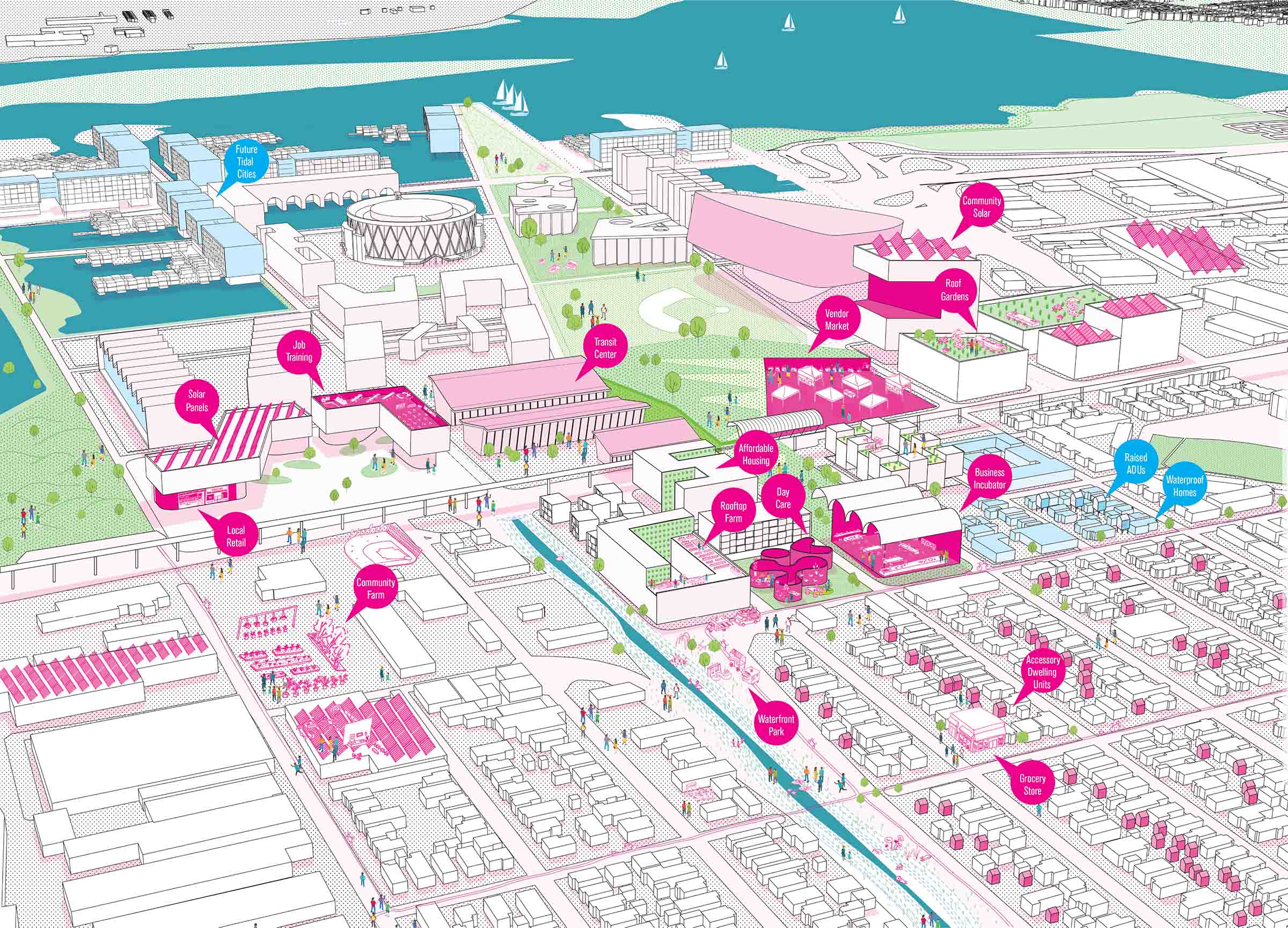

For the 2017–18 San Francisco Bay Resilient by Design Challenge, ten large interdisciplinary teams spent a year working in one of ten sites around the Bay Area, collaborating with residents and public officials to design climate adaptation solutions. Kim’s team, which focused on the communities around San Leandro Bay, included local community organizations, municipal agencies, universities, and design firms. On the design side, members comprised AECOM, CMG Landscape Architecture, David Baker Architects, and Moll de Monchaux, as well as representatives from the Urban Works Agency at California College of the Arts (including Kim) and University of California Berkeley. The above drawing, which shows social infrastructure complementing the incremental construction of floating "Tidal Cities" in the San Leandro Bay area, was one of the project's outcomes. Image credit: Janette Kim/Urban Works Agency

Kim: I think you could describe Resilient by Design as having different spheres, perhaps. Within the inner sphere, the project team, we faced questions of how to construct the team itself and how disciplines could come together. But eventually, and most importantly, there were questions about how to translate between the different ways we work: to understand how quantitative metrics behind, for example, engineering approaches relate to rhetorical questions of rights, housing justice, and public power.

Then there was a wider sphere involving partners that had already been shaping East Oakland and Alameda Island, among other places we were working in. We organized a working group with City agencies like Parks and Planning departments and community-based organizations groups like the East Oakland Collective and the Oakland Climate Action Coalition. Orchestrating those relationships was tricky because, again, there were different politics behind different people’s assumptions. Some of our partners had not been in conversation with each other, and so there were often fears of the others’ agendas.

Another issue was that there was also considerable dissatisfaction among community-based organizations because they hadn’t been part of the jury that paired design teams with each neighborhood. A few community-based organizations around the Bay decided to boycott the Resilient by Design Challenge. So that was another interesting challenge.

When it was confirmed that we could work in San Leandro Bay, we reached out to different groups there and say, “Let’s talk.” At that point, the people who eventually became our partners were kind of wondering, “Should we even call them back?” But we met, and what we said to them was that we wanted to design a process, and not some predetermined image of the city as a series of fixed objects—that we didn’t see this as a master planning process in which we’re telling everybody what we think is right for the site, but rather that we’re creating tools that can help people make decisions. And they’ve told me since that that felt right to them.

Kim presenting as part of the San Francisco Bay Resilient by Design Challenge. Image courtesy Janette Kim

And then the outermost sphere involved people who were not at the table that we needed to take into account. We had organized our team around grassroots community organizations and city agencies that had influence. But we did not, for example, introduce developers to the table: people who, in fact, had the biggest impact on the way the market was shaping this neighborhood. We only had one meeting with an agency that directs development opportunities at the Oakland Coliseum site. [Note: The Oakland A’s baseball team is negotiating with the municipality to build a new stadium, creating the potential for large-scale development on the existing stadium site.] But this was an important exchange, as it revealed, explicitly, questions of race and planning that I think were not being acknowledged in other conversations, and they were really offensive and contentious. We didn’t include those voices at the table for a reason. But at the same time, with adaptation planning, we needed to take them into account.

So what I’m getting at is that the collaborations that my teams have constructed have tried to create a sense of trust so that we could work together. But they also try to acknowledge the distrust and aggressive behavior that does happen in the way that cities are shaped.

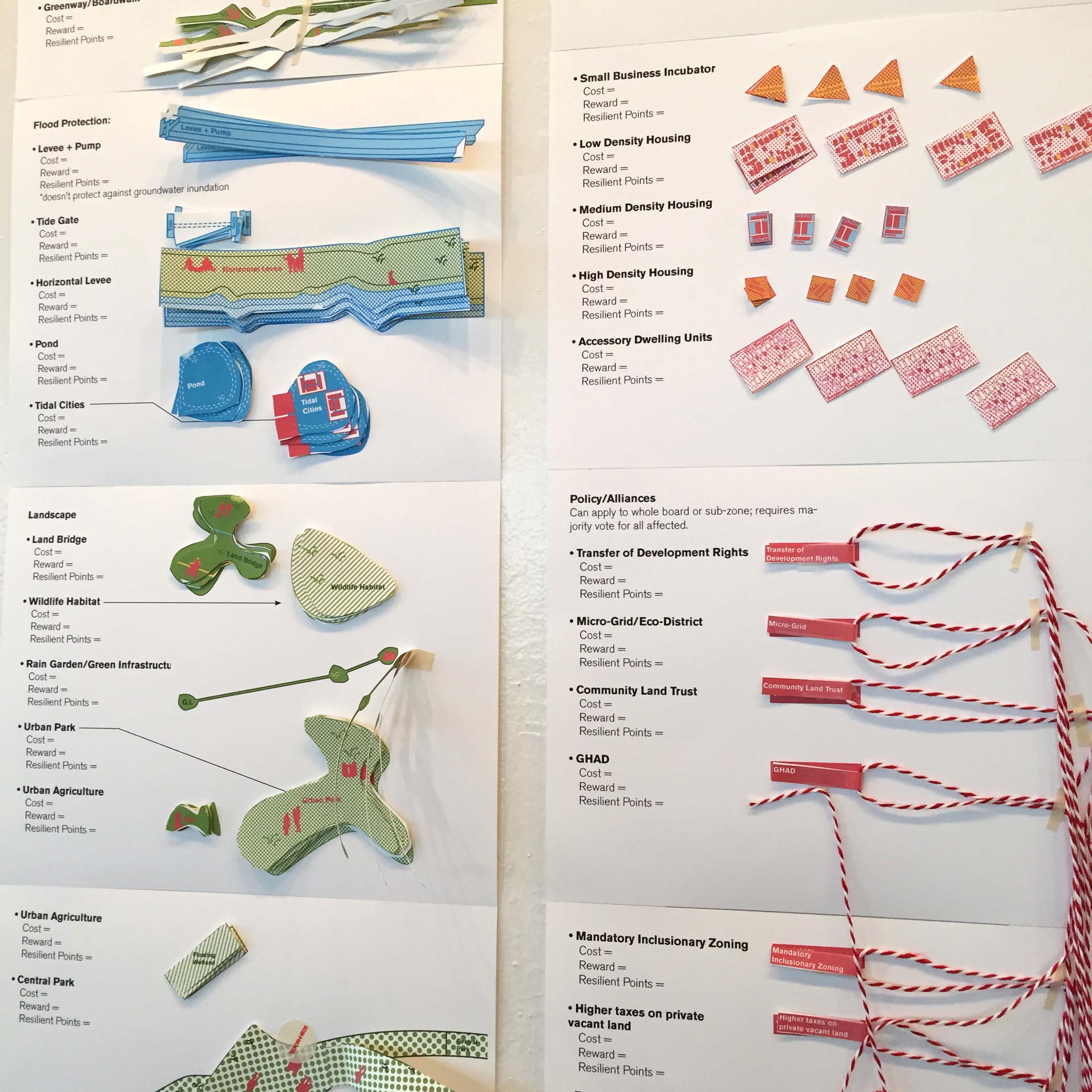

Wesseler: You created a board game for different stakeholders to play in Resilient by Design, and you’ve done the same on other projects. How did you first get started in using games as tools for collaboration?

Kim: When I started to teach and work in climate-related matters, I researched scenario planning, because it seemed like a tool that had a lot of power for helping designers learn to deal with uncertainty. It’s a method one sees a lot in federal agencies, for example.

So I taught a studio in which I asked the students to go through a scenario-planning process. It was extremely boring and I really did not like it. And at the same time, Kazys Varnelis, Jochen Hartman, and Momo Araki had made a game called Symtactics for the Uneven Growth show at MoMA. And so they came and played it with my students, and I asked the students to design board games.

And it was just absolutely fantastic. It allowed us to scheme out those possible scenarios, and to do it in a way that felt so vivid, as a literal space that you can see in front of you. And also as a place of creative interaction and fun and humor.

I started to understand that games are a model, right? I think of games as a cross between an economist’s model, an ecologist’s model, and an architect’s model. You have the logic of how the space is arranged, and, combined with questions of currency, ecology, and resources, all in trade with each other, you can run through the impact these variables can have: for example, different kinds of flooding on landscapes.

So I just loved it. I was like, “This is so fun.” And my students really opened up that possibility for me.

Wesseler: Can you walk me through how people used the game during Resilient by Design?

Kim: We designed the game in parallel to the design process itself. We had a series of four meetings with our larger project working group, and we came to the first meeting with empty stakeholder cards and asked people to explain what their motivations and struggles were. Based on that, I came back to the next meeting with a series of player identities and motives, and that framed out the narrative of the game. Also, at that second meeting, I came with a series of pieces that eventually became Adaptation Tiles in the game, which can be used to prevent sea-level rise or otherwise accomplish those player goals. Some tiles include levees and water pumps, but there are also things like a job training center, affordable housing, a community land trust, or a policy for participatory budgeting.

So we came to the second meeting with those tiles, and even though we didn’t have rule sets for the game yet, our partners debated which of these strategies made sense and started adding new ones into the mix—such as budgeting strategies. And then we played it. I created the rule sets, which in essence, create limits—they stop people from being able to buy everything anytime, so players have to start trading and collaborating with each other.

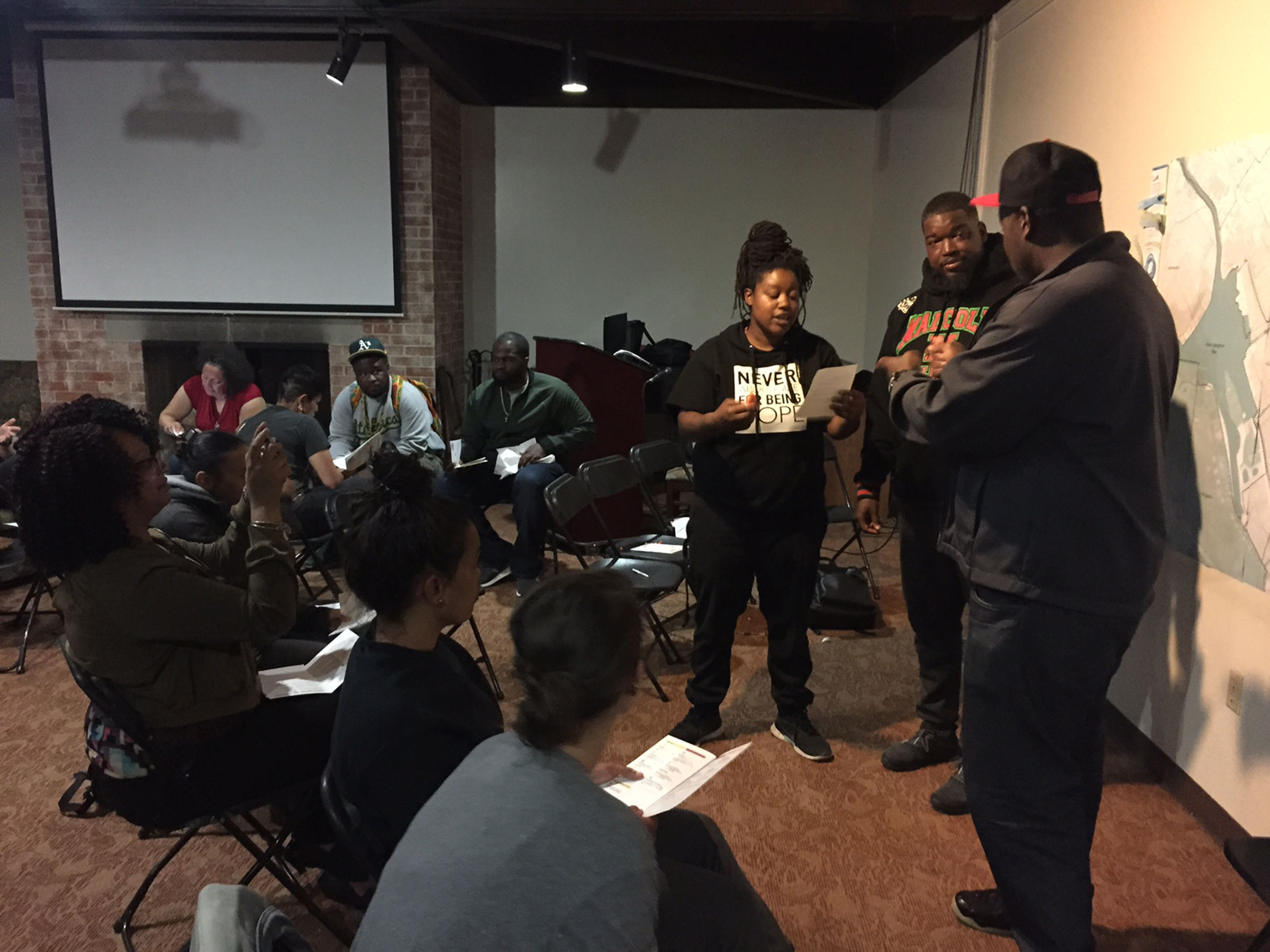

Members of the East Oakland Collective play In It Together. Image credit: Janette Kim/Urban Works Agency

There were many takeaways. One of the very first things we saw was mutual benefits that people do seek out. In San Leandro Bay, communities are clustered around a marshland, called the Martin Luther King, Jr. Shoreline. Initially, our collaborators described this situation by saying, “Well, we’re all so different. We’re really separated from each other because there’s a marsh in the middle of us.” And then when we started playing, I think all of us realized for the very first time, “Oh, the marsh is the thing we have in common. Anything I do to contribute to this marsh is going to benefit you, and therefore we have a reason to work together.”

In some cases, though, persistent kinds of conflict became explicit. During the project, I think one of the hardest things for us to do was talk about disagreements in a frank and productive way—the risk was that we would all be too polite. The game made it just much easier to say, “Oh, this player is interested in housing justice and this player is interested in habitat restoration and this player is interested in making shitloads of money so they can invest in this thing, so we are at odds here.” There was a huge conflict over whether large-scale development was necessary for people to afford shorefront reconstruction and flood-tolerance planning moves. There were people who said, “We need Class A office towers, otherwise we’ll never be able to deliver,” and there were others who were saying, “Wait, you know, this is about building community wealth. Isn’t there a way to understand flood tolerance in relation to community-based grassroots wealth?”

And so the game allowed you to understand what it would look like to prioritize one thing or another and hopefully win either way, and therefore make a kind of political decision and not a technocratically based one.

Members of the Resilient by Design Project Working Group using In It Together. Image credit: Janette Kim/Urban Works Agency

Wesseler: This is probably an obvious point, but it probably also helped that people were able to speak as characters rather than as themselves when playing the game—that they could look at their own situation a bit more abstractly.

You’ve described aspects of your work as translation. Can you discuss this idea and how it relates to collaboration in your practice?

Kim: One of the ways I think about this is through disciplinary translation, which we talked about a bit already. With Rebuild by Design, it was so interesting—you could just see how every discipline had different criteria: different analytic systems, different jargon, right? So, for example, in some cases, the efficiency of, like, urban economics would butt up against, say, values of biodiversity. Or it’s very difficult for someone who’s talking about cultural continuity—like the expression of Black and Latinx culture in East Oakland, for example—to express themselves in a way that’s comparable and relatable to someone who assumes a quantitative understanding of the city, such as someone who’s trying to balance tax income and development profits with sustainable development.

Those two value systems are tough to bring together, right? If you’re going for a grant and you need to prove effectiveness, you need some metrics to prove that, so the quantitative logic is going to rule.

And yet Oakland is an incredibly politically savvy place. Community members really are very aware of the problem with that kind of technocratic thinking, and so even presenting it can wear away at trust. Some community members speak both languages—efficiency and effectiveness as well as rights—and try as much as they can to fuse them. And then there are others who are just saying, “Let’s throw out all the neoliberal planning models and focus more on justice.”

I think making a translation between these perspectives is super difficult. I’m excited that the games do this in a way that’s playful and cheerful, but also direct and disarming.

Interview edited and condensed.

Explore

All Together Now

Through its collective model and emphasis on discussion and debate, Citygroup seeks to move beyond business-as-usual design.

This Land Is Whose Land?

To make infrastructure and industrial sites better neighbors within cities, Landing Studio addresses complex questions of ownership and governance.

Working Groups

Farzin Lotfi-Jam discusses his path to a practice model that foregrounds collaboration.