Interview: TALLER |MauricioRocha+GabrielaCarrillo|

Emerging Voices 2014

TALLER |MauricioRocha+GabrielaCarrillo|

Mauricio Rocha Iturbide and Gabriela Carrillo Valadez

Mexico City-based TALLER |MauricioRocha+GabrielaCarrillo| emphasizes “the importance of the vernacular, craftsmanship, sustainability, and socially responsible design.” Founding principals Mauricio Rocha and Gabriela Carrillo explore proportion, volume, light, and material, with a particular focus on sensitivity to user needs and responsiveness to climate, in their temporary installations as well as their buildings. This robust body of work includes the San Pablo Oztotepec Market in Milpa Alta, Mexico City, which received the Gold Medal VII Biennial of Mexican Architecture; the Plastic Arts School at the Universidad Autónoma Benito Juárez de Oaxaca, which received the Gold Medal XI Biennal of Mexican Architecture; and Cineteca Nacional Siglo XXI, Museum of Cinema, Digital Video Library, Laboratory, Central Patio, and Garage, Mexico City. Current work includes the Oral Judgment Courts in Lazaro Cardenas and Patscuaro; a Four Seasons resort in Tamarindo, Jalisco; and a photography museum in Cuatro Caminos.

In March 2014, on the occasion of their Emerging Voices lecture (video embedded below, also available here), Rocha and Carrillo sat down with League Program Associate Jessica Liss to discuss their practice.

Jessica Liss: This series emphasizes the voice of practitioners. How would you describe your voice?

Mauricio Rocha Iturbide: We are trying to make architecture that really understands problems and solutions as dependent on where you are. And that architecture is social, political, and ethical. We speak in a contemporary language that draws from different traditions of art, culture, and architecture in the history of Mexico. But we are not making Mexican architecture; we are making architecture in Mexico.

Gabriela Carrillo Valadez: Right. Our work is a response to where we’re living, to our places, and to our economic and social situations. In our case, there’s always a crisis, and those are good provocations to act. We know we have a great cultural seed in our country. We believe it is important for global influences to be part of our reality, but we also want to explore what we already have locally.

We had the opportunity to design a garden museum in a very small town outside of Mexico City. We were able to stay in the town and to learn the building techniques of the area from the residents. Their ancestors are the people who designed Teotihuacan! So we aim to translate the traditions and materials of the place where we are working into contemporary work, not through fashionable forms or fireworks, but with what can happen in the space.

Rocha: We try to work with the silence, with empty space and experience. After working with the program and the client, the final idea is that the space wins, rather than the form. And we like the final form to surprise us. It’s a way to be alive and to see that our work changes depending on the opportunity.

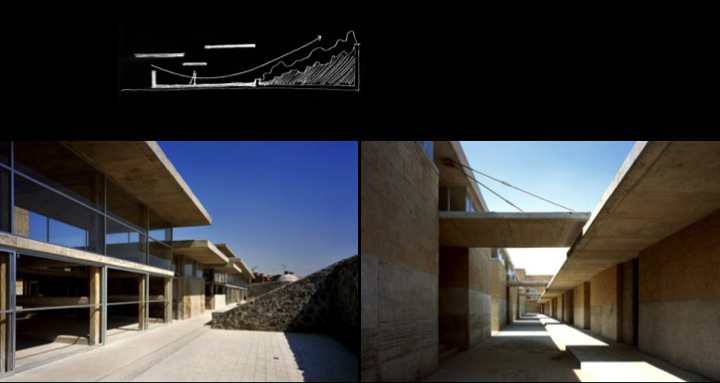

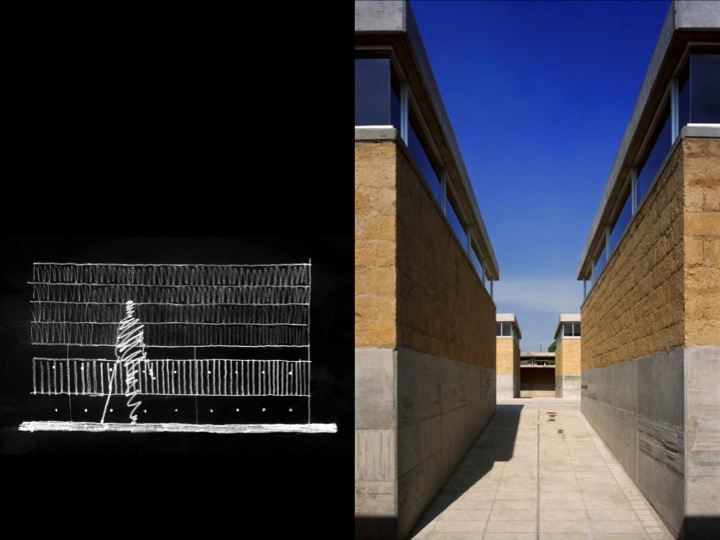

Plastic Arts School, Universidad Autónoma Benito Juárez de Oaxaca | Photo by Luis Gordoa

Liss: As an emerging firm, what do you see as the advantages and challenges to practicing in today’s economic, professional, and intellectual climate?

Rocha: In general, you need constraints and limits in architecture. When people look at economic problems like Spain’s, some architects worry that they won’t have the same opportunities as before the crisis, when there was a lot of money available. But I think Spain has arrived at a good moment in some regards. With lots of money and big possibilities, they began to create very bad architecture. I think good architects will now do something with less money but good ideas. Sometimes, when you work for people with money, you forget to work with limits. You cannot forget to take advantage of the opportunity, for example, to play with new materials.

Past generations of Mexican architects dreamed of working in the United States, Europe, or generally for rich people. With the economic crisis around the world, something happened where the architecture of Mexico, Latin America, Asia and Africa became more important to the world.

Public architecture in Mexico was very important in the ‘20s with Juan O’Gorman, who made very nice public schools and then the library for the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México in the 1950s. Maybe the last moment of great public architecture in Mexico was in the ‘80s with Pedro Ramirez Vasquez, who designed the Museo Nacional de Antropologia. After that, most architecture was being funded by private clients or through big commissions. You stopped seeing the hand of the architect in the design of public buildings, and that was a loss of wonderful opportunities. It is important for our generation of architects to make these buildings again, even if the budgets are small and the timeline is short. Even if it is tiring, it’s exciting and we don’t want to lose opportunities. It’s part of our culture, and it’s important to us to do it.

Carrillo: Dealing with tight budgets also influences our strategy and the materials we use for buildings. For example, for the San Pablo Oztotepec Market, the budget was almost nothing. The client just wanted a market where the rain wouldn’t get in and the wind wouldn’t take away the ceiling, which is what happened there before. They didn’t care if it was fireworks architecture, they just wanted a market for a price that they could pay. And we can create a proposal that is important to us that also meets the requirements of the people as well. As we’ve grown we now have clients with money, but it’s a statement of the office that we will continue doing public architecture even if it is poorly paid.

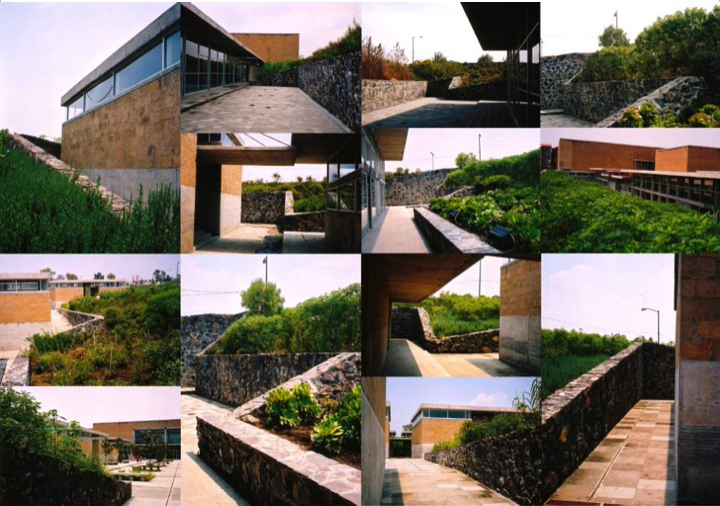

San Pablo Oztotepec Market | Photo by Jaime Navarro

San Pablo Oztotepec Market, before | Photo courtesy of TALLER

Liss: The Market, like a number of your projects, is in deep dialogue with the cultural, social, and physical landscape of its environment. Could you talk about this project’s relationship to the typology of the informal settlement?

Carrillo: When we started work, that place already functioned as a market: the facades were constructed, and there were better established stores selling out of small pavilions inside and others who just strung up canvas informally to take advantage of the site to sell as well. We also had this natural view from the top of the facades over the complex topography of all the roofs. That topography would help define what our ceiling looked like. We had a month to design it and start the construction, and it seemed like common sense to repeat, in a sense, what was already there. The space already had very good ventilation and light. It was more comfortable to shop there than to go inside a building with air conditioning and artificial lighting. The trouble was, they already had a plan to buy this particular type of canvas rooftop from a friend. We said we could do something better at the price the friend had proposed. Our client was ultimately not the government, but the guys who owned the stores, so we had to present the project to the community. They chose our project because they wouldn’t need artificial lighting or special systems to take out bad smells. We never discussed the form; we just talked about the best way they could live in that place.

Rocha: We made a lot of models, and when you see ten different models on the table, you see that they are the same project. It’s somewhat random which is the final design. This randomness is present in the city, and you see it in San Pablo Oztotepec, because its informal houses are changing everyday. If the owners make money, they build another floor. The market, finally, had the same condition as the town in this regard.

Carrillo: This condition of change continued throughout the construction: in the middle they decided to remove the original structures, which were supposed to remain below our ceiling. Suddenly they got the money for a larger redesign, which involved removing the interior. We kept the floor they had, and worked very closely with them to meet their needs, like a place to paint the name of a store and a way to hang fruits. The community is still in contact with us: they are proud that their market is being published and they have come back to us when they’ve needed other renovations.

Liss: You mentioned earlier that your architecture isn’t about fireworks and you talk about the importance of negative space — voids — in your work. Tell us about the precedents that have influenced your design approach and how your architecture is achieved mostly through subtraction rather than addition.

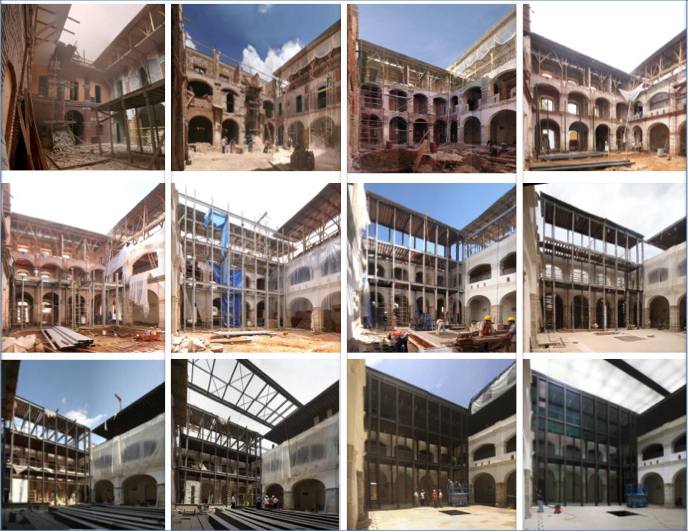

Rocha: It’s important to begin with the idea of ephemeral architecture. It’s about transforming space in a site. You make something in a space, but it may only exist for two months. But for us, these works are just as important as any big building, because they help you to understand what has happened in a place and what you can do to change the experience. To make this ephemeral work, you need to understand this pre-existence. In many projects in historical buildings, for example the temple in San Pablo, Oaxaca, you have to work with different scales, different looks, different ages. And it’s about cleaning out what is not working and seeing what you can do with the empty space to fulfill the program, then underlining the important things already there.

Contemporary intervention and rehabilitation of the Temple of San Pablo and Complex, San Pablo, Oaxaca | Photos courtesy of TALLER

Carrillo: We both share these ideas, and the most powerful architecture experiences that I’ve had are related to voids. We’re great admirers of Japanese architecture, in which the void is underlined. There is a space in Ciudad Universiteria in Mexico City that also does this. The campus is built on beautiful, very black stone left from the explosion of a volcano, and over the years nature has grown into a kind of jungle in places. A group of seven artists decided to create a perfect circle in the middle of this by clearing away the vegetation to reveal the stone.

Rocha: Louis Kahn and the Salk Institute are very important to us as well. When he was designing the Institute, he is said to have asked the great architect Luis Barragán what kind of tree to plant in the main plaza. Barragán said “nothing.” Three years ago I visited the Kimbell Art Museum, and at first I was disappointed, because it was not what I thought it would be. 20 minutes later, I was crying. You have to walk through it, to live in it, because then you see the lights and the tints. Architecture is like this: the first moment is not important; the experience, the life, is more important.

Carrillo: We can explore that in many ways. Even though technology develops so quickly and we have access to these beautiful structural programs, in our case the void is a perfect space for several things. It can permit people to use as space as their own, but it is also the perfect place for light to transform. We’ve just designed some judgment courts, out of stone and in an egg form. Every time I go there, I have a different experience. Depending on the hour of the day, the shadow is more clearly defined, other times it’s blurry, or it’s cutting the building in different ways. Voidness permits that. So instead of focusing on making the forms with material stuff, we want to work with what can’t be touched.

Rocha: Working with light can only be done with time. I don’t understand why so many architects concern themselves with repeating forms. We don’t have much time in our careers. To understand how to control light is something you have to work with, and when you do, it’s incredible.

Liss: How does your emphasis on a multi-sensory experience of architecture fit into the desire for voidness?

Carrillo: We don’t want the view to be the most important aspect of our spaces. For example, right now we’re designing a Four Seasons hotel close to Careyes and Manzanillo on the Pacific Coast of Mexico. There is a very beautiful jungle there, and we want to create a connection between the jungle and the sea. We’re creating what we call a comb, which are thin cuts, two meters or so wide, through the mountain, to make it. We want to have a corridor for walking through the jungle, where you can be 25 to 40 meters away and have a view to the sea and feel the wind as you are walking. You can walk, and then suddenly you feel the wind and see the sea. Our experience designing the school and library for the blind and visually impaired helped us learn to work in this way with all the senses.

Hall for Visually Impaired, Ciudadela | Photo by Jaime Navarro

Liss: With regard to the school and the library, what was your experience designing these buildings, especially in relation to this multi-sensorial idea?

Carrillo: Even though these are buildings for the blind and visually impaired, there are still visual elements that work with light. Most of the visual impairment in our country is a result of degenerative sickness related to poverty, so many people are not exactly blind. We worked with industrial designers and did research into blindness, and we learned that most emergency elements in our cities are yellow because it is the color most visible to these individuals. So we worked yellows and reds into the furniture and the garden. There are also different light conditions, which creates helpful contrasts. The buildings are also meant to be touched, and we want to that to be for anyone, not just the blind.

For the library, we worked with Mauricio’s brother Manuel — who also worked with us on the Sound Pavilion in San Luis Potosí — to commission nine sound installations specifically for the space and to design the acoustics and speakers. When you’re walking through, you start to discover the sounds, and by the end you hear this mixture of sound textures. You can’t touch that, which makes us happy.

Sound Pavilion, Science & Arts Labyrinth, San Luis Potosí | Photo by Luis Gordoa

Liss: You emphasize the importance of vernacular architecture and craftsmanship in your design philosophy. What is the relationship between design and the construction in your projects?

Rocha: We love process, and we love to feel the hand of the worker in the walls, to see that imperfection. We have the opportunity to make things in Mexico, to hand-make them even, inexpensively. The problem is how we translate this craftsmanship to a new, contemporary architecture. That’s a very dangerous moment, because you can easily make a very folkloric or regionalist architecture. We really hate that. Instead, we want to make contemporary architecture that benefits from an understanding of historical architecture vernacular.

Carrillo: In a current project in Michoacán, we are working with artisans that make beautiful bowls of copper. For us, it is a luxury, a privilege, to have the opportunity to learn from these guys.

Liss: What’s next for you and your practice?

Rocha: I think the most important for us right now is to design our time and our daily lives. I don’t know how to say no to a project, so we have a lot of them. But it’s important to do so, because we don’t have the time. How you can you have time to be in the studio, to talk with your friend about new ideas so you don’t repeat your work, then have the time to draw it, and still have the opportunity to travel and learn more to change those ideas?

Carrillo: Or even the time to take a coffee in the middle of the afternoon! We believe that to make good architecture you need a double discipline: you need to live, and you need to work. If you don’t live, your work won’t be what you want. We work all day until 3am. We need to create more balance. And to do good work, you also need time: you need to spend a whole day sitting in the same place to see how light moves or transforms a place to understand it.

Rocha: I am asking: how can we do nothing to make something?

“The Tower of the Winds,” Intervention at the Interior Sculpture of Gonzalo Fonseca (Uruguay) | Photo courtesy of TALLER

***

Mauricio Rocha Iturbide and Gabriela Carrillo Valadez, TALLER |MauricioRocha+GabrielaCarrillo|, Emerging Voices 2014, complete lecture video | Recorded March 20, 2014 | Running time: 52:54

***

Both Rocha and Carrillo graduated with honors from the Faculty of Architecture of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). Rocha has been a fellow and jury member for the National Fund for Culture and the Arts (FONCA) and has, since 2011, served as Academician of the National Academy of Architecture. Carrillo began collaborating with TALLER DE ARQUITECTURA in 2001, serving as Project Director from 2006 to 2011, when the two founded TALLER IMauricioRocha+GabrielaCarrilloI. She has taught at the Instituto Superior de Arquitectura y Diseño (ISAD) and the Universidad Iberoamericana. Both were awarded the 2013 highest prize for professional development, Cátedra Federico Mariscal, by the Faculty of Architecture of UNAM.