On the Table: Dinner with Jesica Amescua Carrera, Stephanie Davidson, Mariana Ordóñez Grajales, and Georg Rafailidis

A conversation with the design duos behind COMUNAL and Davidson Rafailidis.

The League’s annual Emerging Voices program recognizes eight firms with distinct design voices. In March and April, each firm delivers a lecture, then joins prominent architects, critics, and others in the industry for dinner and informal discussion.

In the following, Mariana Ordóñez Grajales and Jesica Amescua Carrera of Mexico City firm COMUNAL: Taller de Arquitectura and Stephanie Davidson and Georg Rafailidis of Buffalo practice Davidson Rafailidis discuss participatory design, drawing, and architectural typologies.

Stella Betts, Leven Betts Studio: Both firms have a very open-ended process, which leaves you more vulnerable to unanticipated circumstances. I’d be curious to hear about a time when something went wrong, or something happened that you really didn’t expect.

Mariana Ordóñez Grajales, COMUNAL: In the participatory design process, we always start out by having conversations with the community. And when we were working on the Rural Productive School in Tepetzintan, one of the first things the students proposed was a parking lot on the top of the mountain.

Jesica Amescua Carrera, COMUNAL: Their teacher, Maestro Pablo, has a car. No one else in the community has a car, but the professor has a car. So they proposed a parking lot.

Ordóñez Grajales: It fell to us to guide a conversation about how cars are used in the town. That got them to start thinking, “Oh, no one here has a car. Since no one has a car, does it make sense to put a parking lot on top of the mountain?”

We asked what they might like to see the land used for instead. In the end they created a sports complex.

Betts: Stephanie and Georg, do you have a funny story?

Stephanie Davidson, Davidson Rafailidis: I have an idea, but it might make Georg mad!

Betts: That’s already funny.

Davidson: Once we were working on an addition to a midcentury house. The addition was complicated geometrically, and we were trying to figure out what angle the new roof should be.

Georg was working alone on the project one day, and our interns and I came back and saw these circles and completely crazy, amorphous shapes cut out for this space. In these shapes were other shapes, and it looked almost like my five-year-old got hold of the foam cutter. It was completely not controlled or logical, like my studies were.

So—I feel so badly, because, together with the interns, I was laughing at Georg! We said, “Oh, Georg, since you got tenure you’ve really lightened up!” We thought the shapes were really funny.

They sat there for a couple of weeks—until everyone realized they were the best options for the project.

I really appreciated at that point how important intuition is, and how difficult it is to actually understand why some things work formally.

Georg Rafailidis, Davidson Rafailidis: You want more stories like that? When we got a guest professorship in Toronto, we proposed these big paper huts cast from pulp. Everyone was excited at the beginning, but I think they didn’t realize that we were really serious about it.

Student working on a paper hut as part of a University of Toronto studio. Credit: Davidson Rafailidis

A lot of the paper casts literally ended up on the surfaces of their new building, covering large areas.

One day the cleaning personnel was not aware of what they were, and they cleaned one of them up!

Davidson: They threw it in the garbage.

Rafailidis: Days of work from the students.

Paul Lewis, LTL Architects: Most of the drawings shown in tonight’s lectures aren’t conventional architectural conceptual drawings. Both firms are expanding the agency of the architect into different realms. In the process, have you fundamentally changed your relationship with drawing?

Amescua Carrera: In our case, the drawings come more from the community than from us. The line between what the community proposes and what we propose is very thin. Sometimes when you construct the project, you cannot say which ideas came from the community and which came from us.

We think it’s a success where both ideas join to make a new way of seeing architecture.

Davidson: We enjoy working in a lot of different types of drawing. They don’t always look good. They’re not always legible. Sometimes they don’t even work. We haven’t perfected anything.

Sean Anderson, MoMA: Thinking about drawing makes me wonder how both firms communicate with your clients. When COMUNAL is asking students to project what they may need for their school, for example, what is your role, besides facilitator? Is there interpretation?

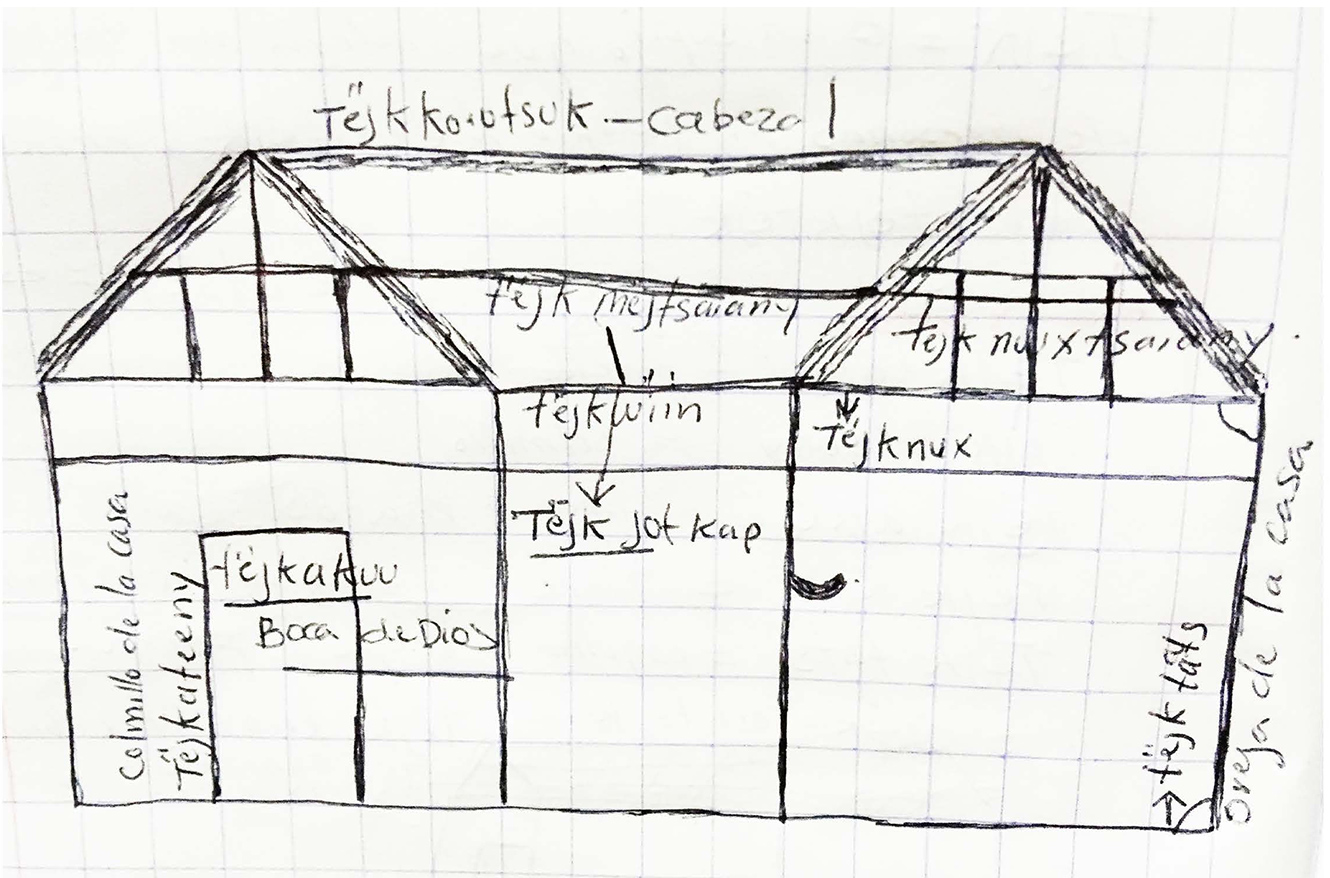

Amescua Carrera: We try to create a dynamic where the community can draw all the things they want. Also, they can express the symbols behind their traditional architecture. That way we can really understand the elements that compose vernacular architecture.

In our presentation we showed a drawing that was made by Silviano, one of the inhabitants of Tepetzintan. In that drawing, he expressed years of years of traditional thinking. He said that the door was the mouth of God, the interior was the stomach of God, and the facades were the ears of God. Those elements make us understand the importance of each part of vernacular housing.

A traditional house and its components, as drawn by Silviano Faustino, a resident of the small town of Coatlán, Oaxaca.

Also, with the students we understand through the drawings how the space is going to be organized in the school.

So the drawings are made more by the community than by us. We’re the interpreters.

Lewis: I’m not sure I believe that. The level of intricacy of the house you showed, the clarity of the structure, the complexity of the inlay, the way the brick patterns are developed: that level of articulation wasn’t present in any of the vernacular buildings you showed. The assembly of all those things was incredibly rich and refined, and I have to believe that, as architects, you had a role in that, and you’re not just simply a neutral absorber of traditions.

Amescua Carrera: Those drawings are the first stage from where you begin to design. After that, you propose another thing and they listen. From there, they also gain new knowledge, and you establish a link between both knowledges.

For example, the structural systems are also designed at full scale with them. We do not use drawings for that. We experiment with different ideas, joining one piece to another at full scale.

So it’s a mix of drawings and full-scale models and our thinking and their thinking.

Ordóñez Grajales: The window screens in both houses we showed, for example, are the kind traditionally used in these areas. The diamond shapes used in the first building are a very important element of pre-Hispanic Mexican culture. They’re used in women’s clothing.

When we came to Tepetzintan, we asked people how we could learn about the different communities and where they’re located. They told us that there are no maps—the maps exist in the clothes. Every community has its own diamond and its own specific design, and that’s how they know where each person comes from.

Amescua Carrera: They also use this shape for many parts of their architecture.

Ordóñez Grajales: Their entire cosmic vision is in the culture and in the shapes. So we know that you can’t draw a construction system if you don’t understand it.

Amescua Carrera: Only after we really understand their traditional building system can we propose technical improvements.

Rosalie Genevro, The Architectural League of New York: Both firms are radically open to readings of the existing environment, which is not necessarily typical of most architects, who want to impose a different kind of vision.

At what point in your career did that become the case? What caused you to take that approach?

Rafailidis: For me it was during my thesis at the AA [Architectural Association School of Architecture]. My case study was the Stalinallee in Berlin. What I found so interesting is that the conventional way of describing the building talked about socialist realism and these kind of delicate ceramic tiles that made it look like a wedding-cake style of Stalinist architecture.

I thought that was a weird way to think about it, because these tiles actually fell down after one year because it was so quickly built. When they put these tiles on it was freezing, and of course the cement was not good. So they fell down. But no one actually looked at the physical reality of the building and said, “It actually looks more like a brown rock thing.”

The building immediately shed off the original intention. It was built to represent a political system, but that’s not what it’s actually about.

That for me was like, “Okay, one can charge an object until a certain moment, but at some point it talks back. It’s totally independent.” The existing built environment has its own agency and is talking back to us, if we are listening.

Amescua Carrera: We started taking this posture because we saw the incongruency between the materials that are imposed on rural communities and the realities of those areas. Materials like concrete are not necessarily the best option for these kinds of environments.

Ordóñez Grajales: There’s also the fact that in Mexico there’s a huge indigenous population that doesn’t receive the benefits of architectural services. It’s similar to what happens with medical care, education.

We believe that architecture could make a huge difference in these places. It could really increase the quality of life.

Audrey Wachs, The Architect’s Newspaper: What’s one thing you’ve learned from the other practice that you might be able to use in your own work?

Rafailidis: This world which you were describing is very unknown, for me at least, but you showed that this is the reality in Mexico. There are a lot of areas with their own materiality, their own economy, their own culture, their own way of building.

These things are still connected to one another, not globalized in a way where everything is like, you get the same stuff from Home Depot and that’s your only option.

That this non-industrialized economy still exists is a big revelation for me.

Davidson: What resonated with me most was how you’re empowering the people you’re working with to harvest things within their immediate reach to make buildings.

Ordóñez Grajales: And you showed something that we don’t typically do, which is consider multiple uses for a space. This could be very interesting for us.

David Leven, Leven Betts Studio: Both firms are working so intensively on pre-existing buildings or in established communities. What would you do in a situation where you’re starting from scratch?

Rafailidis: If there’s an existing building, you add an episode to it, but if you start one, you need to charge it with as much energy as possible to make it ready for a journey.

For example, thinking about the Bentham Panopticon, it was a prison. But If someone puts us in in that building now, it might form the most amazing architecture school.

That’s what we tried, maybe, for the studio: to make it so intense that people will just relate to it. No one will tear it down because they’ll think, “No, no, this could be this or that.”

Davidson: It’s difficult to answer, because we’re driven so much by our constraints, even if they’re invented constraints. We always have these unrealistically low budgets—and we impose those on ourselves, too, because we know that if we realize something for ourselves, it would have an unrealistically low budget.

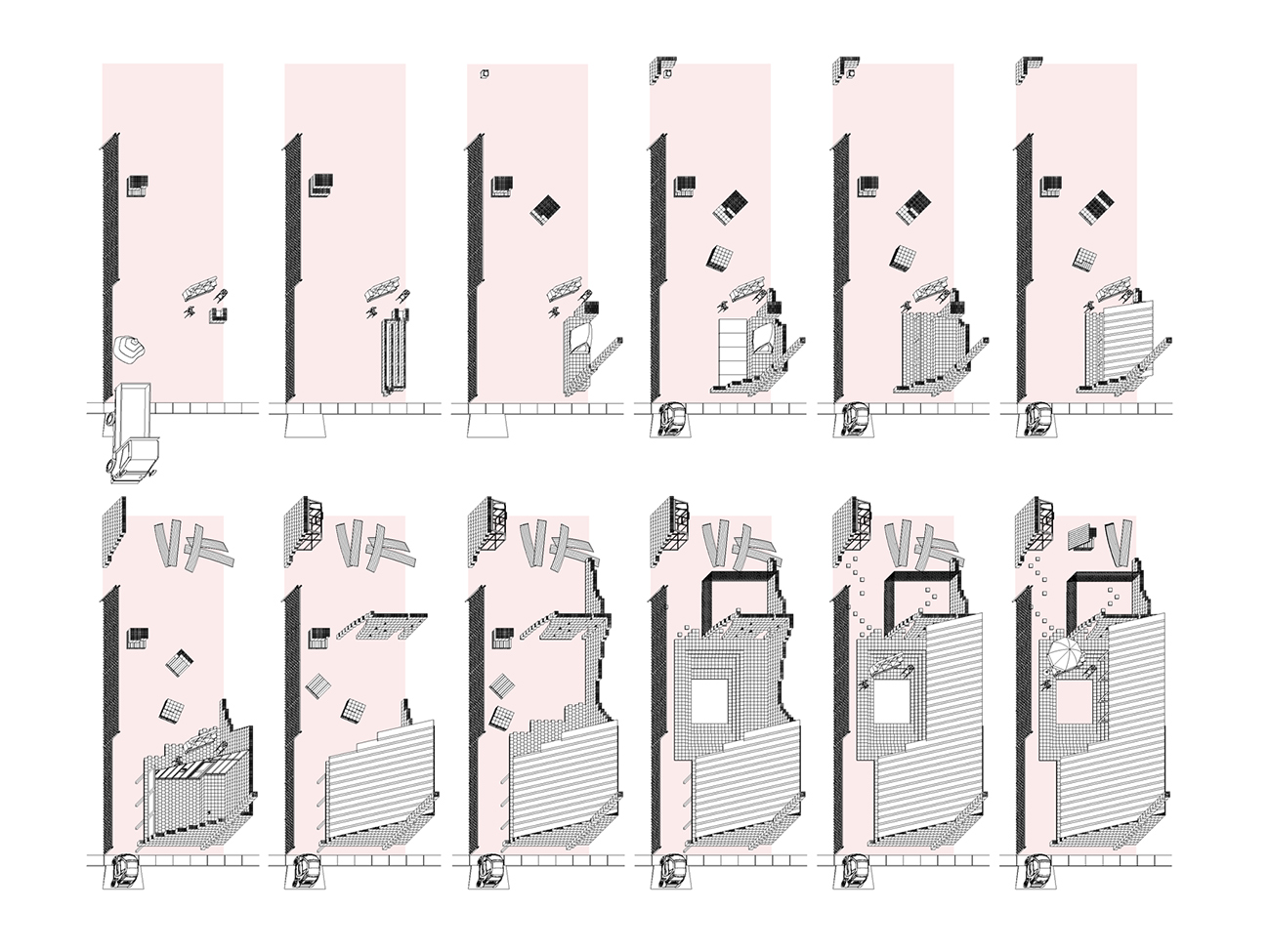

So coming from that, there was actually one earlier phase of our Continual Construction project that used a lot of prefab chunks. It was very different than the additive approach we showed tonight, where the construction was more brick by brick. If we started that project, we’d have to reconcile which method would work better.

Leven: It’s kind of like an Aldo Rossi concept, where the piece of the city that’s constructed changes its use over time. In that case, these digestible, kind of reductive formulations of architecture are what the architect does.

Rafailidis: The writings of Aldo Rossi are super interesting, but the idea of these fixed types: that’s what we resist a lot. For us, it’s much more idiosyncratic and personal. The idea that there’s a set of typologies that every person relates to, that it’s that simple: that’s what we have problems with.

Lewis: But I’ll go back to David’s point about what happens when you have to design for a site that might be more of a tabula rasa. You’re arguing that you don’t rely on typology, but He, She & It seems to be incredibly based on platonic solids: rectangles, triangles, known geometric types. So are you really that resistant to typology, or is it in fact all about the geometry or basics? I’m still curious about what you do when you can’t rely on local constraints.

Rafailidis: We’re not resistant to typology, but that can’t be the only thing. The geometry is one part of He, She, & It, but there’s so much more than that: the types of materials, how the light goes in, the fact that the budget was so low that parts of the building still look like a construction site, so that it’s like, “Oh, is this already done?” Which we like. These things cannot be captured by typology alone.

Amescua Carrera: Also, even when there’s not a preexisting physical space, there is often a mental space. People’s ideas and traditions shape the design process.

Ian Volner, journalist: What would happen if we dropped each of you in your respective towns and set you to work? Do you think you would be able to apply the same kind of approach that you’ve applied in Chiapas in Buffalo, and vice versa? Is your work place-specific, in other words?

Ordóñez Grajales: We never replicate architectural designs. What we replicate is the methodology, which is always based on the resources at hand: economic, natural, and social. And that’s specifically where we start: from an understanding of the place, of what exists there, of the society. Through dialogue with the people who are in a place, we can design together.

Rafailidis: Maybe just a short answer… I just love displacement. We had this big displacement when we came from Germany, and Stephanie had a displacement from Canada to Germany. So the thought of it I just find so exciting.

Davidson: We will swap with you!

Rafailidis: I really would like to do it.

Text edited and condensed.

Explore

City as border zone

Architects Ersela Kripa and Stephen Mueller, founders of El Paso firm AGENCY, discuss the reality and rhetoric of the US–Mexico border.

Frida Escobedo, Taller de Arquitectura lecture

Escobedo explores the concepts behind projects in Mexico, the US, and Portugal.

On the table: Dinner with Manuel Cervantes Cespedes, Ben Aranda & Chris Lasch

Emerging Voices winners discuss constraint, minimalism, and how to "client-proof" a building.