Interview: Surfacedesign, Inc.

Emerging Voices 2014

Surfacedesign, Inc.

Geoff di Girolamo, James Lord, and Roderick Wyllie

Geoff di Girolamo, James Lord, and Roderick Wyllie, principals of the San Francisco landscape architecture and urban design practice Surfacedesign, Inc., focus on creating landscapes that “connect people to their built environment” with an emphasis on “personal histories and connections between culture and natural environment.” The firm, established in 2001, has designed projects in and beyond the Bay area, ranging in scale from domestic projects, to the Golden Gate Bridge Plaza, to Stonefields Quarry Park in Auckland, New Zealand. Among the firm’s current projects are the Auckland International Airport Gateway and San Francisco Embarcadero Plaza. In March 2014, on the occasion of their Emerging Voices lecture (video embedded below, also available here), di Girolamo, Lord, and Wyllie sat down with League Program Director Anne Rieselbach to discuss their practice.

Anne Rieselbach: This series emphasizes the voice of practitioners. How would you describe your voice?

Roderick Wyllie: One interesting thing about this award for us is that it provided an opportunity to reflect on what our voice might be. Over the last seven years we’ve been busy, maybe hysterically busy, trying to realize projects, and to a large extent, we didn’t set out with an agenda to put forth a specific voice. We’re also of a generation that doesn’t have a strict ideological attachment to how we practice as designers. All that said, I think our voice is one that is diverse in terms of actual form-making, but, whether through cultural references or the ground itself, there’s always an attempt to derive the form from the site.

Geoff di Girolamo: Our office started out with more projects abroad than at home, which gave us an interesting perspective. Because we were coming in from the outside and quickly immersing ourselves in the client and local context, we were able to look at a project fresh and ask people really fundamental questions about the place: what’s its history, what’s the attachment to it, what are the client’s values about the place? That approach, developed through those experiences, is certainly part of our voice.

IBM Honolulu | photo: Surfacedesign, Inc.

Rieselbach: As an emerging firm, what do you see as the advantages and challenges to practice in today’s economic, professional, and intellectual climate?

di Girolamo: All three of us went to school during the recession in the early ‘90s and were studying with professors who were trying to scrape together a practice. I was at UCLA, studying with people like Dagmar Richter and Thom Mayne—they were getting a lot of attention, but their practices weren’t really about building; they were focused on drawing, publishing, and assemblage. Building things at that time was either too pragmatic or uninteresting. I think it was thrilling when the profession, in the late ‘90s, really started building things again. We are excited by—and very committed to—building projects. Whether something is going to come of a project is a benchmark for whether we find it worthwhile to pursue.

Wyllie: To an extent we are located in an economic bubble. We felt the drop in 2008 for sure, but we have all worked for a variety of firms and learned to identify what we think of as unnecessary excesses in a lot of design studios—to be very lean. In a way, it was an exciting part of starting our own firm, to have an opportunity to engage in every level of the practice.

We’re also witnessing a dramatic transformation of San Francisco, where we’re based. It can be awkward to see so much of its history transform, but on another level, it’s thrilling to see a city change so dramatically in such a short period of time—and to have the opportunity to participate in that. We can do the work we’re committed to and hope that it’s contributing to a different urban condition in a really positive way.

di Girolamo: One of my concerns about the boom in San Francisco is that not everybody contributing to it is being asked to be good corporate citizens of the city, which as urban designers we’re very concerned with. There’s a real opportunity now to capture not only money coming into the city, but the public imagination about what the city could be. We want to participate in that re-imagining. It would be unfortunate if all we really got out of this moment were a bunch of luxury towers. We are interested in new opportunities to create parks and other spaces in the public realm or to advance the arts in the city.

James Lord: In the time that we have been practicing, since, say, the mid-‘90s, our profession has emerged as a real leader in the transformation of public space. It’s exciting to see the sustainability work, the brownfield remediation strategies—that landscape architects have been doing for a while—now catching on.

Stonefields Quarry Park | photo: Marion Brenner

Rieselbach: A number of your projects—for instance, the Stonefields Quarry Park in Auckland—reclaim brownfield sites. How do you integrate remediation with aesthetics?

Wyllie: It’s our training to embrace the remediation solution as one that has an intrinsic aesthetic value, and to retrain the user’s eye to view it as inherently beautiful because it tells that story of who you are. Whether that’s being able to provide some level of interpretation for the reclamation project or working with native plants, that is part of the aesthetic.

Lord: The best landscapes begin with an understanding of the soil that you’re sitting on. Whether it’s a toxic site or a greenfield site, we have to understand the soil makeup and the hydrology so that we can appropriately deal with it.

The Stonefields site was a volcanic landscape that had been mined for basalt by European settlers in New Zealand. So, in essence, the site became a giant bathtub that contained all the water that hit it. So we had to consider how to deal with that water. We allowed the low point of the bathtub to be a wetland park, and then we choreographed a system of integration and re-use of the collected water, which is cleaned as it moves through the wetland and then is used in the toilets and in the irrigation system.

Rieselbach: You’ve described your work as emphasizing personal histories and connections between culture and environment. What are the design ramifications of this relationship between history and site?

di Girolamo: We sometimes use the word “archaeology,” because we dig deep into personal and community histories. We try to reveal something that people have forgotten about or that has been covered up by time. And one way we connect people to these built environments or restored natural environments is by developing stories about them that are rooted in forgotten histories.

Wyllie: But the projects work on many levels. I don’t think of them as purely didactic. To the extent that we aim to reveal the history of the site and connect it with personal histories, that’s the way we enter into the project. At the end of the day, we’re just as concerned that the user finds the experience exciting, stimulating, or provoking.

Horno3 Museo del Acero, Monterrey, Mexico | photo: Paul Rivera

Rieselbach: You work at an incredible variety of scales, from expansive developments to intimate gardens. What does that residential work provide for you and how does it benefit your larger projects?

di Girolamo: In the beginning, we relied on smaller residential garden projects to sustain our practice. And there is a very large emphasis in our work on investigating how things are made. Our residential practice affords us an educational opportunity to continually expand our knowledge of how materials are used, which helps us on bigger projects.

Wyllie: What’s so great about residential projects is the intimate relationship you develop with a client. In a way, you’re trying to bring them along a journey that’s really about them. And I’m really proud to be part of a whole history of garden making. I don’t see where landscape architects derive a deep understanding of creating space without embracing gardens, and I never want to abandon making them because we’re doing bigger projects.

di Girolamo: I think unfortunately gardens and grand avenues have become bad words, in a way, because they’re not seen as for the people. They’re seen as the practice of the wealthy. In San Francisco, it’s been interesting and frustrating to see the rise of the “parklette.” Parklettes are these small public spaces “reclaimed” from metered parking spots. They arose out of Park-ing Day, an annual event that asks designers to come up with ideas for how to repurpose parking spaces. I think the original impulse of raising awareness about how the city deals with public or open space is great. But what really upsets us about it is that people are treating the public realm like it’s not that special. Parklettes have become a way for the city to not really spend political and economic resources to create open spaces in the city. They typically don’t last very long because they’re not made of durable materials, and they often end up serving restaurants rather than the public. But this kind of grassroots park effort has made the city re-evaluate other easy options to reclaim open space: closing down streets, taking over intersections. What you end up with are crappy public spaces on top of asphalt, and the livability of the city isn’t really changed all that much. They haven’t even hired anyone to do asphalt parking lot repair. I understand there are limited resources, but people aren’t addressing, in a visionary way, how we can occupy the city and have open space.

Wyllie: From an urban design standpoint, it’s discouraging. Having a parking space as your public park is really not good enough!

Lord: I think, in part, it’s a lack of oversight. You can take small steps to improve our streets, but do it in a holistic way. Look at Valencia Street in San Francisco. There, all the city did was widen the sidewalks, plant street trees, layer in a little of the culture of the neighborhood. Now you have a rich, viable street where you didn’t have one before, and without huge public investment. And that’s through landscape architecture. I just want to emphasize that parklettes are not landscape architecture.

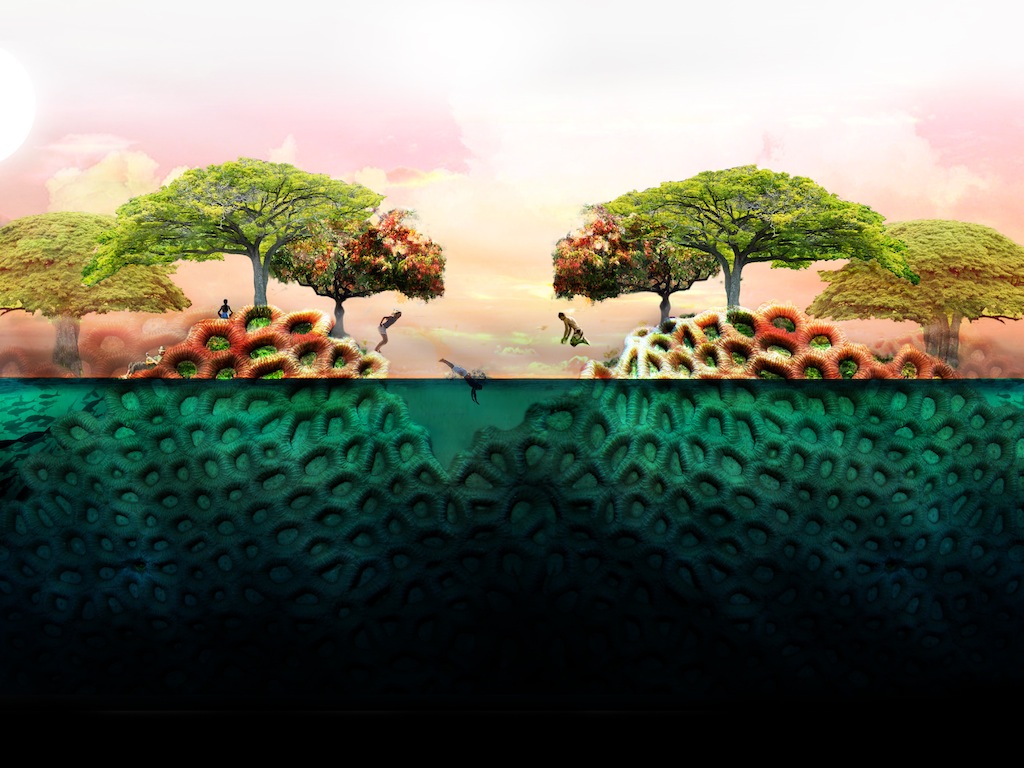

Click any image to launch a slideshow with more images of Surfacedesign’s work | Presidio Anza Bluff Park, San Francisco | rendering: Surfacedesign, Inc.

Rieselbach: This ties together a lot of the things that you’ve been talking about in terms of what landscape architecture really is: path, or experience, or something more unitive. What is landscape architecture at its most elemental, and what role does it serve in a city?

Wyllie: We are trying to connect forgotten or neglected spots into a larger vision of the city and to allow people to access them. Increasingly, I’m interested in landscape design as a wild, a place of relief from the rigid and somewhat clinical structure of the urban environment.

di Girolamo: We see our work as sometimes a foil or counter point to the dogma of architecture so as to engage people with buildings and landscape in a different way.

Lord: I stand back in awe when I look at our forebears like Olmsted. He really understood the way people live and how cities work. Prospect Park, for example, acts as a stormwater receptacle, a functioning landscape, but it’s also a breather for the city, a counterpoint to the city.

The biggest problem with the urban environment that I see right now is that our public spaces have become homogenous. We have the exact same street curbs, the same manhole covers, and we’re not allowed to use a different material because someone might trip. If you proposed a cobblestone street like Bond Street’s now, it would never happen! But how beautiful is it to hear it, to run over it, to see the shadows and the way the water hits it—it’s poetically beautiful. Landscape architecture is about challenging the way we build infrastructure, how we treat our road systems, how everything impacts our natural systems when it leaves the city, and what kind of environment we walk through. You walk down a tree-lined street with brownstone stoops, and everyone’s sitting on them. It’s more than the pavement or the trees: it’s about engagement with the street and with your fellow citizens. We want to harness that sense of curiosity, of engagement, to create rich environments in which people want to meet their neighbor or have a cup of coffee.

•••

Geoff di Girolamo, James Lord, and Roderick Wyllie, Surfacedesign, Inc., Emerging Voices 2014, complete lecture video | Recorded March 6, 2014 | Running time: 43:16

•••

Geoff di Girolamo received his M.Arch. from the University of California, Los Angeles. James Lord and Roderick Wyllie both received their B.Arch. degrees from the University of Southern California and M.L.A. degrees from Harvard University. All three principals have served as guest critics at schools including California College of the Arts, and the University of California, Berkeley. Wyllie has also served as a Visiting Professor at Ohio State University. The firm’s awards include a New Zealand Institute of Landscape Architects Award of Excellence, a National Honor Award from the American Society of Landscape Architects, California Home + Design Award for Landscape Design, and the Green Good Design Award.