The rural South Beach area of southern Grays Harbor County and northern Pacific County is a story of change and adaptation: geophysically and socially, but also economically.

Water, land, harvest, and trade have connected place and people along this stretch of coastline for thousands of years. Those now identifying as the Shoalwater Bay Tribe, for whom this is an ancestral home, describe the area pre-colonization in terms of its bounty and many villages.1“About the Tribe,” Our Lands, Shoalwater Bay Tribe. European settlement and the origins of the modern local economy brought significant transformation—not only to the population, but to the landscape and nearshore environments. Settlers and subsequent generations constructed towns and outlying habitation; laid networks of roads; dredged and engineered waterways; constructed jetties, marinas, and lighthouses; and managed wetlands and tideflats for agriculture and aquaculture. Economy and the promise of gain both drove and benefitted from reshaping nature.

This reflects the story of America and westward expansion. What sets South Beach apart, and what makes its modern-day residents distinctly vulnerable, are physical and environmental forces continually altering the region—an eroding coastline, sea level rise, ocean acidification—and the certainty, albeit without certainty of when, that a large-magnitude offshore earthquake and resulting tsunami will emanate from the volatile Cascadia fault. Resilience in this environment rests on people’s ability to mitigate and adapt.

The dynamic geophysical and adaptive social backdrop provides an interesting frame in which to view the region’s linked economy. As in much of the rural West, South Beach has diversified its jobs base over time, yet remains reliant on natural resources (directly and indirectly) for a large portion of its economy. It is also dependent on its civic spirit, relying on residents to actively support community wellbeing.

A number of factors are stressing historic industries and community composition. Some create opportunities; others threaten to undermine foundations of the local economy. While we cannot know what the future holds, it is interesting to consider the sources of change and ponder what they might bring.

A Framework for Considering Change

Change happens for different reasons, and that is especially true in South Beach’s complex economy. One framework for grouping drivers of change is to consider their nature:

- Marketplace dynamics

- Environmental dynamics

- Social dynamics

These three factors are affecting numerous South Beach industries, but notably several iconic markets significant to both the local economy and local culture: commercial fishing, oysters, cranberries, and tourism. Social dynamics are also altering South Beach’s composition, with economic implications.

Spotlighting these examples reveals the dynamic forces shaping the local economy and the issues facing this determined coastal community.

Marketplace Dynamics: Commercial Fishing in Westport

“Once upon a time in Westport, we valued our small community, the feeling of closeness that you can only have in a small town. We valued our fishing industry and the jobs that it provides; diverse cultures and people coming together; the cranberry industry; our schools; and our community gardens. We liked that we have lots of beaches where you can even see bald eagles; you wouldn’t find that back home in Indiana. The weather here is so nice that the tourists come visit us—there’s only 30 degrees variation during the year, and no snow. We liked that it’s not heavily industrialized or commercialized, not torn up or denuded; it’s still beautiful and untouched. There’s green everywhere. You can see deer, see elk; you can go crabbing for dinner. Anyone here can go get a fresh seafood meal and it doesn’t cost a fortune. You just have to take the time and go sit on dock with the others who are out there trying to catch their dinner. Everyone here is coming together to make things better, for us all to grow and prosper. And we value our traditions.”

— 2018 Coastal Resilience Workshop participant

Commercial fishing has been a cornerstone of the Westport economy since the 1880s. Its impact is outsized. According to NOAA Fisheries, a department of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the small Washington city was the thirteenth-largest fishing port in the US in terms of landed weight in 2018 (the most recently available data), and it has been in the top 20 since 2002.2BST Associates, “Port of Grays Harbor Westport Marina Demand Analysis Revised Draft Report,” January 28, 2020. Hauling in between 80 and 150 million tons annually, its fleet tops all Washington fishing ports. Comprising between 150 and 180 commercial vessels ranging from 30 to 100 feet, the fleet pursues a number of species, but relies on hake in terms of volume and Dungeness crab in terms of value.3BST Associates, “Port of Grays Harbor Westport Marina Demand Analysis Revised Draft Report,” January 28, 2020.

The numbers, however, conceal another story that has been unfolding for some time. While catch compares well across ports, commercial fishing and related jobs have declined in recent years. NOAA estimates that what it calls “Living Resources” jobs—commercial fishing, fish hatcheries, aquaculture, and seafood processing—dropped over 15 percent in Grays Harbor County between 2005 and 2017. The self-employed subset of the category, largely representing commercial fishers, dropped 14 percent.4Office for Coastal Management, “Employment: Living Sources,” January 14, 2020.

What’s behind these figures? Commercial fishing is a complex global market, but a few factors appear to contribute to an overall issue of costs growing faster than revenues. For example, the market price of Dungeness crab—Westport’s most valuable and most sought-after catch in terms of boats fishing—has held stable for the better part of the last decade, while permits and other costs have continued to rise. Likewise, some fisheries, such as salmon and sardines, have been in decline or a cyclical low in recent years. Where historically fishers relied on one primary fishery, today’s most successful operations run boats that can easily participate in multiple fisheries and travel further to do so. Smaller boats and those dedicated to one fishery, on the other hand, have difficulty making ends meet.

One result of this dynamic is a significant barrier for would-be entrants into commercial fishing. Consider: A typical boat in Westport is 50 feet in length, which—with gear—can run $400,000 or more. A Dungeness crab permit, for which commercial loans are not available, can cost an additional $225,000. Add in other required costs, and it can total upwards of $1 million to enter the market with a small boat that has fewer options than its larger competition. It is a gamble in a profession without guarantees of success.

The consequence of such market demands has been fleet and permit consolidation amongst fewer ownerships, increasingly centering on those operations of a size better suited to weathering the cost and risk. The trend is by no means limited to Westport; fleets across Washington, New England, and elsewhere are experiencing similar trends.5Industrial Economics, Incorporated, “Marine Sector Analysis Report: Non-tribal Fishing,” Washington Coastal Marine Advisory Council, October 21, 2014. “Pressing Challenges Facing the Commercial Fishing Industry,” Saving Seafood, January 15, 2011.

Westport’s commercial fishing heritage consists of small operations comprising generations of families, one succeeding the next. Fleet consolidation is the result of contemporary market realities. How these two marry is a question many are contemplating.

Environmental Dynamics: Oysters in Willapa Bay

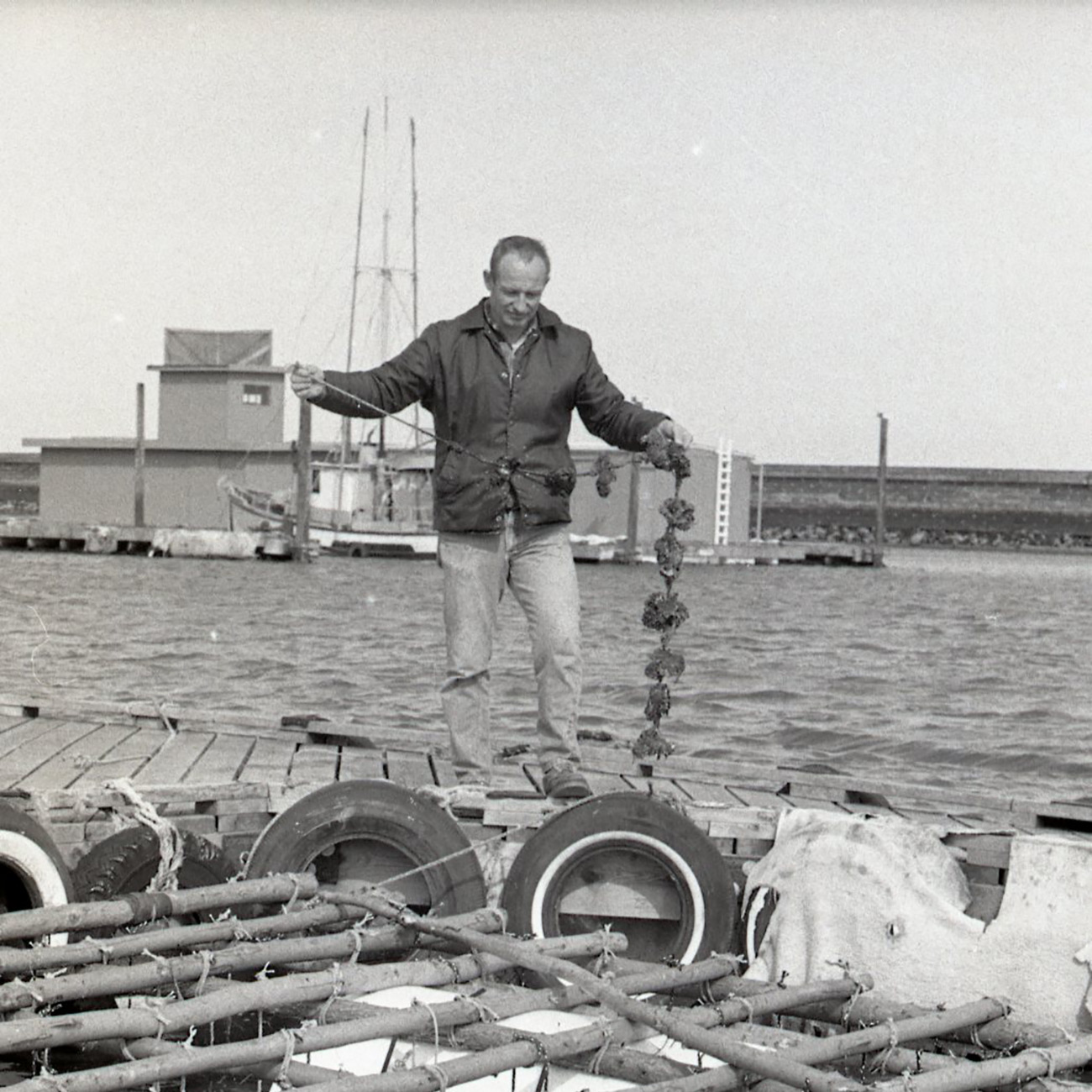

Brady Engvall harvesting oysters grown on suspended aquaculture, circa 1970. Photograph courtesy of the Westport South Beach Historical Society

Willapa Bay in northern Pacific County is the second-largest estuary on the West Coast. It is also one of the largest oyster-producing areas in the world—and is the largest in the US.6Lee McCoy, “About the Bay,” University of Washington Ruesink Lab, March 19, 2013, accessed February 11, 2021. First established as a commercial industry in the late 1800s, Willapa Bay farms, combined with those in southern Puget Sound, are the backbone of a Washington oyster market that accounts for over 80 percent of US West Coast sales.7Alan Barton et al., “Impacts of Coastal Acidification on the Pacific Northwest Shellfish Industry and Adaption Strategies Implemented in Response,” Oceanography 28, no. 2, (2015). Locally, oyster farms are the largest private-employer category in Pacific County; shellfish aquaculture accounts for more than 1,500 jobs.8Northern Economics, Inc, “The Economic Impact of Shellfish Aquaculture in Washington, Oregon, and California,” prepared for Pacific Shellfish Institute, April 2013. Although there are niche markets for others, the prominent species grown and sold is the Pacific oyster. Originally brought to the US from Japan in the early twentieth century, Pacific oysters comprise more than 80 percent of the market.9Alan Barton et al., “Impacts of Coastal Acidification on the Pacific Northwest Shellfish Industry and Adaption Strategies Implemented in Response,” Oceanography 28, no. 2, (2015).

Oysters can be grown a number of ways. “Bottom culture” is the traditional farming method in Willapa Bay, where oysters are grown directly on tidelands for most of their life cycle. It requires that the substrate be firm enough to support the oysters’ weight. The alternatives are “off-bottom” methods, where oysters are suspended by various means.

While the market for oysters remains strong, environmental forces are increasingly stressing production. Of specific concern are a native crustacean and a pH imbalance.

Left: Shipping container and oyster farm, Tokeland, Washington. Credit: Eirik Johnson. Right: Tideland infested with burrowing shrimp near Tokeland, Washington, 2016. Photograph courtesy of Damian Mulinix, for EO Media Group

Burrowing shrimp, often called ghost shrimp, are native to Willapa Bay. Whereas in the past the shrimp were controlled by natural predation from green sturgeon and other species, impervious native Olympia oyster reefs, and surges of freshwater from the wild Columbia River, circumstances have changed.10Sandi Doughton, “Back to the Drawing Board for Control of Oyster-Killing Shrimp,” The Seattle Times, August 10, 2015. Green sturgeon are endangered, Olympia oyster reefs are largely gone, and the Columbia is dammed. These facts, combined with factors such as warming ocean conditions, led to a proliferation of ghost shrimp starting in the 1950s. Natural controls were replaced by chemical controls—notably carbaryl, a powerful neurotoxin—for several decades; however, this was phased out in 2012. Since then, alternative controls have proven largely ineffective, while alternative chemicals remain unpalatable to officials and portions of the public.

Why the concern with ghost shrimp? They burrow into tideflats in search of food, loosening beds and promoting turbidity. Oysters subsequently sink and die, at great cost to farmers.

Quite different from the local problem of ghost shrimp is the effect of slowly acidifying ocean water stemming from global carbon pollution. Given offshore conditions, Washington is particularly vulnerable to ocean acidification—the impacts of which may be heightened in nearshore waters. Oysters and other shellfish are susceptible to its effects, particularly when forming shells. Lower pH slows growth rates, causes shells to become thinner, and leads to greater mortality. This bore out between 2005 and 2009, when widespread failures at Pacific Northwest oyster hatcheries due to an influx of acidic seawater resulted in the loss of billions of oyster larvae.11Washington State Department of Ecology, “Ocean Acidification Blue Ribbon Pane.” These failures provided a glimpse of what to expect in the future.

The combination of burrowing shrimp and acidity shine a light on the many challenges facing current and future generations of Willapa oyster farmers. Whether the answers lie in alternative controls, alternative cultivation, alternative stocks from selective breeding, alternative hatchery locations, or something else, what is clear is that oyster farming is subject to changing environmental conditions that demand adaptive practices.

Environmental Dynamics: Cranberries in Grayland and North Cove

Commercial cranberry production in Grayland and North Cove dates to the 1870s. The 60-plus family farms encompassing roughly 1,000 acres along this stretch of coastline are the largest contributors to Washington’s $6.2 million cranberry industry.12United States Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service, “Wisconsin Ag News — Cranberries,” USDA NAAS cooperating with Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection, June 18, 2019. “Coastal Erosion Threatens Cranberry Bogs,” Storm Water Solutions, Scranton Gillette Communications, November 26, 2018. The majority of growers are members of a regional cooperative with Ocean Spray, which purchases between 85 and 90 percent of the cranberry volume produced here. Many cranberries are processed at the local Ocean Spray facility in Markham, where—since the 1990s—they are dehydrated for the company’s Craisins® brand. While the facility made sauce and juice in the past, fruit bound for these products is now processed out of state. Though a minor percentage of the overall market, nearly all fresh cranberry fruit for the West Coast is produced in the region.

Cranberries are a global business, with nearly a third of volume going overseas. Present-day farmers must understand issues that largely did not affect their forebears: rules around chemicals and residues, tariffs and taxation, shifting international demand. Add to this typical challenges associated with farm life—family planning, weather, harvest—and a complex picture emerges. These, however, are not the primary long-term concerns for many local cranberry farmers.

The cranberry bogs of Grayland and North Cove are situated atop historic wetlands, very near the coast. These watery areas proved well-suited for cranberry growing and—peculiar to this region—dry-harvesting. Operations are highly dependent on drainage ditches, which take freshwater away from bogs, and tide gates, which keep saltwater out. The tide gates are particularly important, as saltwater intrusion is devastating for cranberries. Herein lies a mounting concern.

“We chose to focus on an 11 percent chance of one-foot rise by 2060, recognizing the assumptions that these predictions are made based on current information of climate change, and projections could be different. Under this scenario, we would lose access to Aberdeen. The road would be under water in the Ocosta curve. Up by O’Leary Creek would also be under water and the bridge would be inadequate. We would lose the airstrip. The [Elk River] Bridge would be a difficult situation. This is an opportunity because there are other reasons to replace the bridge and straighten the curve other than safety under sea level rise. In South Beach we have a history of successfully moving roadways because of encroachment.”

— 2018 Coastal Resilience Workshop participant

Washaway Beach is the fastest-eroding shoreline on the Pacific Coast, losing upwards of 100 feet annually in recent decades. State Route 105 and the southern tide gate are the primary means for keeping saltwater out of hundreds of acres of North Cove cranberry bogs. Efforts to limit erosion near the tide gate have been made, but it remains an unresolved concern as the shoreline continues its retreat.

The issue is compounded by the future threat of sea level rise. Under likely scenarios, the University of Washington estimates North Cove will experience a roughly one-foot rise in relative sea level by 2100.13P. Lavin, H.A. Roop, P.D. Neff, H. Morgan, D. Cory, M. Correll, R. Kosara, and R. Norheim, “Interactive Washington State Sea Level Rise Data Visualizations,” prepared by the Climate Impacts Group, University of Washington, Seattle, 2019, updated July 2020.Existing infrastructure is inadequate to address the implications of such conditions at Washaway Beach.

At greatest risk are North Cove farms in the immediate vicinity. Grayland farms—situated on higher ground—are not directly threatened by coastal erosion. That said, risk is nonetheless shared. The local industry is small enough that any loss of volume threatens its viability as a producing region. As such, the encroaching ocean is an unsolved, growing concern for local farmers. While long-term solutions are pursued, the future of South Beach cranberries may hang in the balance.

Social Dynamics: Tourism in Westport

Salmon charters return for their weigh-ins at the Pogie Club Salmon Derby, 1957. Photograph courtesy of the Westport South Beach Historical Society

Tourism has been an important aspect of Westport’s economy for over 100 years.14Kate Kershner, “Westport — Thumbnail History,” History Link.org, Association of Washington Cities, February 23, 2014. Many consider the 1950s through 1970s its heyday. The city was then widely known as “the Salmon Capital of the World,” reinforced at its peak by 260 charter boats making one, sometimes two trips a day with as many as 20 people each.15Tom Banse, “Charter Fishing Fleet Casts Wary Eye Toward Possible Fishing Cutbacks To Save Orcas,” Northwest Public Broadcasting, April 24, 2019. Sport fishing generated upwards of 250,000 angler-days during a busy 100 days of summer, slowing down after Labor Day.

Fewer salmon, in part a result of lower hatchery production, combined with more stringent rules, quotas, and changing recreational preferences, were hard on Westport’s sport-charter fishery. By the late 1990s, Westhaven Drive, Westport’s main commercial route, had replaced charter-boat offices with stores and restaurants catering to non-fishing visitors.16Lynda Mapes, “A Heritage Lost – Coastal Washington Salmon Economy In Ruins,” The Seattle Times, April 12, 1998. For today, Westport hosts only 20 to 27 traditional charters and, depending on the fishing, another 20 smaller, transient charters coming from out of town.

“Once upon a time there was a family of three bears…. The traffic and stress of Chicago drove him out here, dragging his wife with him. They moved to a small community on the coast of Washington. He fell in love with the place that had one stoplight that was shut off after Labor Day and not turned back on until Memorial Day … They liked that everyone knew everyone; and people were independent. They liked that there was a community value of hard work. Westport kids got up early worked harder than any other kids they had seen. There were seven- and eight-year-old kids cleaning fish on the docks in the mornings, and the children of businesspeople worked for the family business. They liked the general quality of life; it’s probably the most giving community they had ever witnessed. When people need something, people rally around and get it to them. They didn’t like that the community was resistant to change. Over the past 40 years, this has changed; this community now wants to move forward in every way possible.”

— 2018 Coastal Resilience Workshop participant

Long-time locals say tourism, broadly, is not what it once was. Various marketing efforts to attract people to town—for example, nautical-themed building design standards—were sparsely implemented and ineffective at bringing the business community together. Ferry service between Westport and Ocean Shores was established in the mid-1980s, only to shut down in 2008. The Great Recession was withering.

Today, however, there is reason for enthusiasm. Lodging tax revenues, a rough indicator of visitation, have risen 60 percent since 2012 (after accounting for inflation).17Tim McMahon, “Historical Consumer Price Index (CPI-U) Data,” Inflationdata.com, Capital Professional Services, LLC, September 11, 2020. Lodging tax revenues 2000-2019 provided by City of Westport, September 28, 2020. People are coming for all variety of reasons. Once a deeply held secret for a small community of surfers, Westport is now Washington’s premier surf town, bringing visitors through October. Nearly twenty miles of uninterrupted, sandy coastline draw families and beachcombers. And Washingtonians of all stripes, eager for alternatives to out-of-state travel during the COVID pandemic, flocked to Westport’s maritime museum, historic lighthouse, shops, and galleries last summer—bringing crowds unseen for many years. Local state parks reported that 10,000 more cars had visited by August of 2020 than had visited in all of 2019.18Shelby Miller, “Westport Businesses Thriving during COVID-19 Pandemic,” KIRO 7, Cox Media Group, August 18, 2020.What is causing the most excitement amongst the tourism set, however, is an active proposal for a Scottish links–style golf course at Westport Light State Park, overlooking the Pacific Ocean. While the concept is still under review by the state, its potential impacts draw speculation—from a need for more lodging to potentially lengthening the local airstrip to accommodate larger airplanes.

Most agree the future is bright, if uncertain.

Social Dynamics: New Neighbors in South Beach

Residence in Grayland, Washington. Credit: Eirik Johnson

While South Beach has been a tourist destination since the early twentieth century, it remained for much of that time a small, tightknit community. In many ways it continues to be. The regional population between Westport and Tokeland has been steady over the past 20 years.19“Small Area Estimates Program,” Office of Financial Management, September 23, 2020. Comparatively, Washington’s population grew by 30 percent in that time.20“Historical Estimates of April 1 Population and Housing for the State,” Office of Financial Management, June 29, 2020.

Population counts, however, veil an undercurrent of change in community composition. While the community is rooted in multigenerational families, many young people are leaving in search of opportunities. In their place are newcomers, a large percentage being retirees seeking South Beach’s charms and relative affordability. Although population has remained relatively stable, the region’s median age has risen roughly 14 percent since 2010.21“Population Change.” The Washington Coast Economist, Sea Grant Washington.

“Once upon a time there was a sleepy fishing village with more salmon than they knew what to do with. As the resources dwindled, people didn’t stop coming, so the town diversified. It added services, recreation opportunities; so that full-time residency could be more convenient here in Westport. We value that we are a small town that has a can-do attitude and working-class mentality. Westport has banded together not only for recreation services, but also health services, food services, and an operational marina, which is pretty unique—not many communities have a big marina like that.”

— 2018 Coastal Resilience Workshop participant

Not only are there more new residents, there are more part-time residents. During the same period, from 2010 to 2020, total housing stock in South Beach grew nearly 9 percent, whereas total occupied housing grew less than 1.5 percent. North Cove occupied housing dropped 11 percent this past decade.22“SAEP Census Block Groups.” Washington State Geospatial Open Data Portal, September 19, 2019.With a median single-family home price of under $200,000, local real estate professionals expect more new residents and second-home homeowners to enter the market—despite a greater than 12 percent increase in home prices in the past year.23“Westport WA Home Prices & Home Values,” Zillow, Inc.

Though some longstanding residents resent the influx of new neighbors, many welcome new investment in the community. Five new businesses opened in Westport in 2020, a notable addition to the Chamber of Commerce. New residents are also creating demand for restaurants and coffee shops—businesses fostering community interaction and cohesion. And unlike the experience in many transforming destination regions, new residents of South Beach reportedly seek opportunities to know and engage their adoptive community.

How the benefits and costs of a changing face of South Beach balance over time is an open question. Similar transitions have occurred across Washington and the rural West, yielding a spectrum of outcomes to consider.

In the Offing

COVID-19 had a perhaps surprisingly positive impact on South Beach’s tourism-based businesses in the summer months of 2020, but it harmed other parts of the local economy. Westport Shipyard, a staple regional employer since 1964, was forced to terminate 347 employees in March—149 of them based at its Westport facility. As of early October, only 17 percent of those were back to work, with no certainty as to when the operation will fully restaff. Both cases serve as a reminder that the South Beach economy, however diversified, is of a size and nature that feels the weight of change.

Resilience in this environment rests on people’s ability to mitigate and adapt. There is much reason to believe this will continue to be true of both the landscape and livelihoods in the future.

◊

The author would like to thank the following individuals for their contributions to this piece: Molly Bold, Port of Grays Harbor; David Buegli, Willapa-Grays Harbor Oyster Growers Association; Stephen Buxbaum, The Evergreen State College; Harry Carthum, Westport Property Development; Kevin Decker, Washington Sea Grant; Leslie Eichner, Westport-Grayland Chamber of Commerce; Kevin Hatton, HB Cranberry LLC; Jamie Judkins, Shoalwater Bay Tribe; John Shaw, Westport South Beach Historical Society; Margo Tackett, City of Westport.

Biographies

is vice president of policy and programming at Forterra, a Washington-based nonprofit focused on land use and regional sustainability. Swenson develops the policies, tools, and programs necessary to achieve expansive growth management and community development goals throughout the central Cascades and Olympic Peninsula regions of Washington State. His portfolio currently includes regional and local land use policy and consulting, conservation and mitigation markets, mass timber market development, recreation-based economic development, and urban forest programming. In 2019 Swenson was on a UW Runstad Fellowship team with Robert Hutchison that studied coastal community resilience in Japan.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.