Prototypical solutions

By Brian McGrath

In 1987, the League collaborated with the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development to launch a design study on the potential of small-scale infill housing to contribute to the city’s affordable housing needs. The Vacant Lots project culminated in an exhibition and publication, portions of which are republished here on archleague.org.

In the following essay from the 1989 Vacant Lots publication, architect and member of the organizing committee, Brian McGrath comments on design proposals consciously conceived as prototypical solutions.

Ten sites were selected for specific housing designs in the Vacant Lots study project. However, with an estimated 3-5,000 buildable vacant lots in New York City, the necessity for prototypical solutions is evident. While many of the proposed designs responded to the context of the specific site, others were consciously conceived as prototypes. In discussing prototypical solutions for infill housing, it is useful to categorize the designs according to the different types of sites found throughout the city.

Sites 1 and 8 are long, narrow, through-block lots. Several designers used this site condition to re-evaluate the traditional morphology of exclusively street-fronted buildings. The proposals by the Ed Mills team and by Craig Konyk, Adrienne Montare, and Thomas Savory for Site 1 disperse four small buildings separated by open courtyard spaces along the length of the site. Seftei/Lynch and the Chester B. Winthrop team employ similar massing on the upper floors of their designs for Site 8.

Daniel Heyden/Robert Goodwin, Site 5

Site 2 is a corner site, situated at the intersection of streets built up with two different housing types: the row house and the apartment building. This site invited hybrid solutions and mixed-use buildings. Sandra Ford’s project contains two separate buildings, one for housing and one for community facilities. Dan lonescu’s design incorporates the repetitiveness and individuality of the row house with the shared facilities and convenience of the apartment building.

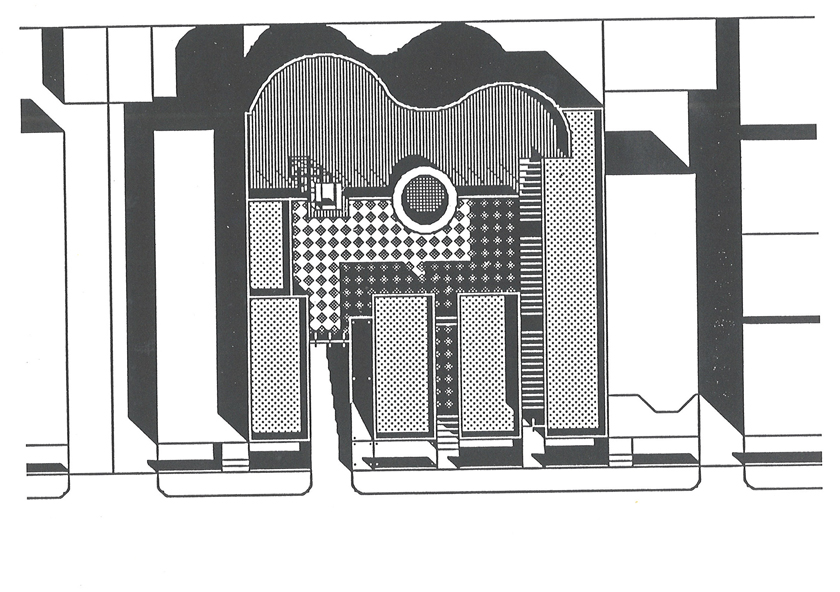

Heyden/Goodwin’s mixed-use project for Site 5 combines owner-occupied row houses with rental garden apartments, while the Agrest and Gandelsonas project, designed by Kevin Kennon and Brian Swier, joins collective living spaces with detached houses, juxtaposing opposite housing types.

Agrest & Gandelsonas, Site 5

Mid-block sites vary in width from the single lot to sites with several contiguous lots. For Site 4, Fairbanks/Jaffe use single, narrow lots as gateways to back gardens. Rather than filling the “missing teeth” with housing, they suggest social uses such as daycare centers. Multiple-lot sites often resulted in court or mews type buildings.

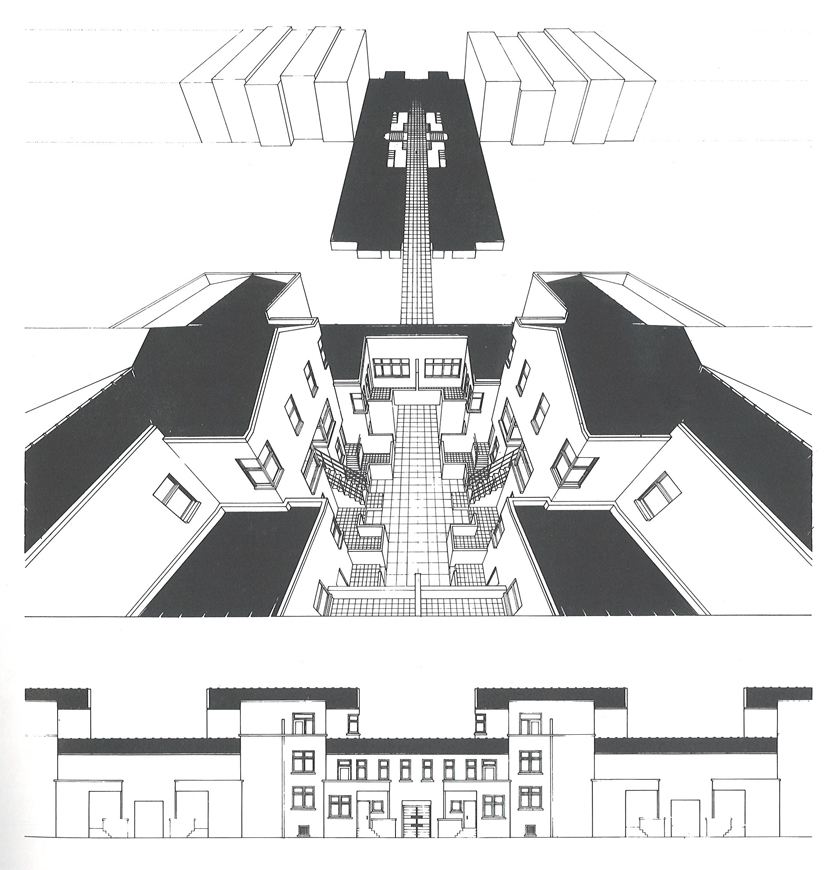

Karahan/Schwarting’s proposal for Site 3 and Gans/McGrath/Robbins’s plan for Site 5 utilize front-entry courts to provide residents with semi-private space for safety and identity. The mews/court project of Richard Plunz employs a side, rather than a street-front court. This prototype is designed to be reproducible in mirror-reflection units to form longer chains of units.

A number of projects address the issue of the enormous quantity of vacant land throughout the city. In their “maximum infill” proposal for Site 1, Anderson/Schwartz create a greater density while maintaining traditional street heights. Saunders/Heidel’s design for Site 8 arranges one midblock and two streetfront buildings in a pattern that can be repeated. Likewise, for Site 9, Carol Latman proposes a modular pattern of four-story double-duplex buildings around open spaces. All three schemes can be repeated over much larger areas than the single vacant lot.

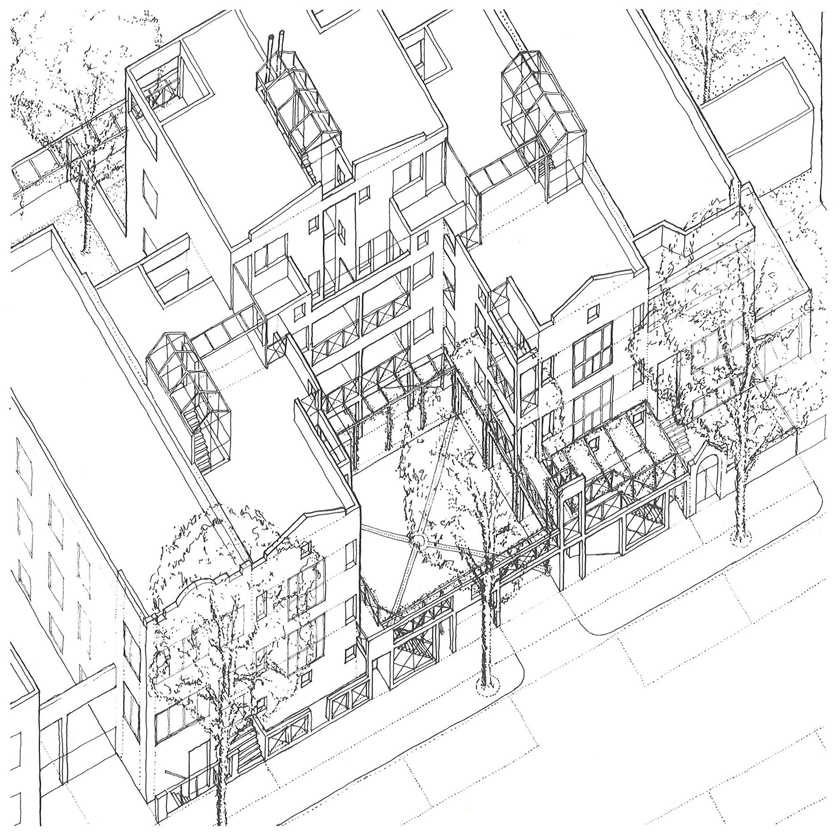

R.A. Plunz with Day, Flynn, Ho, Josephson, Rosenbaum, Smith and Sollohub, Site 1

In the examination of prototypical solutions, several generalizable concepts have emerged. 1) Back-to-back lots, when considered as one site, offer the advantage of exploring new housing types which redistribute the volume of the building over the whole length of the site. 2) Single open lots are often better utilized as much needed open space or locations for social services otherwise lacking, such as daycare centers. 3) Wider multiple-lot sites offer the opportunity to utilize semi-private courts. 4) Hybrid solutions can combine the scale and identity of the row house with the economics and social advantages of multiple dwellings.