On the Table: Dinner with Neri Oxman, Gabriela Etchegaray & Jorge Ambrosi

Two 2015 Emerging Voices were joined by prominent architects, critics, and others in the field to discuss material innovation and building "with the least noise possible"

The League’s annual Emerging Voices program recognizes eight firms with distinct design voices, each invited to lecture throughout the month of March. Following each night of lectures, the evening’s two presenting firms were joined at dinner by prominent architects, critics, and others in the field for informal and lively conversations.

In the following conversation (which has been edited and condensed), Neri Oxman of MIT Media Lab, Gabriela Etchegaray and Jorge Ambrosi of AMBROSI | ETCHEGARAY, and dinner guests discuss material intelligence, the hand of the craftsman, and building “with the least noise possible.”

Guests joined 2015 Emerging Voices Neri Oxman of MIT Media Lab and Gabriela Etchegaray and Jorge Ambrosi of AMBROSI | ETCHEGARAY for dinner following their lectures

Billie Tsien, Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects: You both talked a lot about materials. Neri, you spoke about genetically modified plant material and self-producing materials. Have you done any research in materials where you found out something that frightened you?

Neri Oxman, MIT Media Lab: After we completed Silk Pavilion, I was approached by researchers who are genetically engineering silkworms to produce stronger silk. The question came up whether to explore a second construction of the same pavilion using genetically modified silkworms, which could produce silk with better strength, resilience, and flexibility. When faced with the opportunity to hack the domesticated silkworm at the service of the dome’s structural performance is when I got scared. The place where you choose not to intervene simply because you can is the place where good judgment supersedes opportunity. Design is not for entertainment alone, it involves values. And values have repercussions.

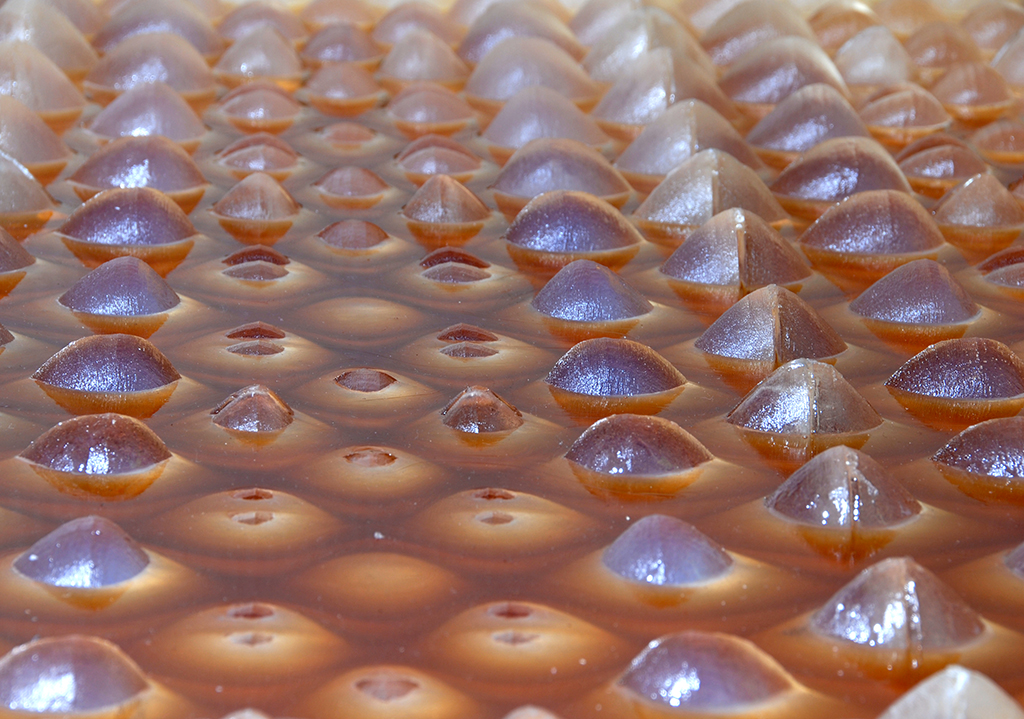

Top view of the Silk Pavilion as approximately 6,500 silkworms construct the fibrous composite structure | Photo by Steven Keating, courtesy of Mediated Matter

Bill Menking, The Architect’s Newspaper: What bothered you about a genetically modified silkworm? Haven’t we always done that with organisms and animals?

Oxman: With bacteria and mushrooms, yes, but to a much lesser extent with animals. Designers, especially those tapping into synthetic biology, are like gardeners. We can choose to interact, intervene, or interrupt. Ultimately we manage and shape our environment. It’s a complex question and one I am still grappling with, but that was also the first time I felt I needed to stop, take a breath, revisit my value system, and move on.

Susannah Drake, dlandstudio: Gabriela and Jorge, there’s something really wonderful about the elemental nature of the materials that you’re working with — what is a true use of material and what is a responsible use of material? It seems like there’s a lot of care that goes into your choice of materials and that those materials have meaning over generations.

Gabriela Etchegaray, AMBROSI | ETCHEGARAY: I think that what we do is really easy to understand — materials are used as they are. We try to link materials with the heritage or the memory of the users or the site. What Neri does is really complex and interesting, but it’s a completely different language than what we do. Even though Neri referred to her work as “architecture,” I wondered, is this architecture? I asked myself, where is this edge where we, as humans, feel comfortable with these investigations? Even though I admire this work!

Oxman: The more I learn from nature and the biological world, the more I discover how close it is to craft and craftsmanship. In both milieus, expression is tied to code and technique, not divorced from them. This worldview is very different than the one we’ve adopted since the Industrial Revolution, where materials are processed with machines to be formed into discrete parts and assemblies with little variation. In this respect, I strongly relate to your work and was so deeply moved by it. You operate in the spirit of nature, letting the material be what it wants to be.

Etchegaray: I would say that we’re talking about the same subjects. We try to synthesize our work as much as we can so that the elements or the space have the least noise possible. And when I see your work, it’s the same — straight to the point — but more complex in other ways.

The IPM Mezcal house and production plant by AMBROSI | ETCHEGARAY | Photo by Omar Vergara

Menking: I think your work is really investigating culture the way that Neri’s investigates materials. I think that rammed-earth wall in the mezcal factory was really wonderful. You’re taking the mezcal tradition, the land, and the building tradition and combining them together.

Jorge Ambrosi, AMBROSI | ETCHEGARAY: Something that I think relates across both of our work is that we’re trying to put aside a little bit of our rational intelligence and impulse to control things how we want them to be. With the silkworms, for example, we see that they have an intelligence in the way they are working, but it’s an intuitive intelligence.

Art, most of the time, is intuitive intelligence more than rational intelligence. It requires putting aside some part of the brain — I don’t know exactly which part — to try to do something more straightforward, in a way saying, “I already know that.” And I think that’s a delicate process, because we can over-rationalize. We have to be more like the silkworms. And I think that’s what we all, in some way, are trying to approach: more irrational thinking, more intuitive thinking.

AMBROSI | ETCHEGARAY’s CGP House | Photo by Rafael Gamo

Nature has an intuitive intelligence that creates efficiency in everything it does. It does not throw away any amount of energy to do something useless. We approach projects and the materials that we use in Mexico with efficiency of resources in mind all the time. As architects, we are always dealing with the budget. When a client tells you, “You have an unlimited budget,” you believe that there is something wrong — that’s not a real commission. Efficiency of resources is always at work. And in Mexico, the hand of the craftsman, or the construction worker, is the cheapest hand that we have. So we’re not going to put in an aluminum panel facade, because it’s much more expensive than having three bricklayers put one brick on top of the other. So, unconsciously, Mexican construction is the same as the worms’: it’s naturally developing in a way that efficiently uses resources.

Annabelle Selldorf, Selldorf Architects: Except that those systems get totally perverted, right? In America, we’ve seen that at a certain time something is considered more efficient — building shopping malls became the model of efficiency in somebody’s mind, and it made reasonable sense because it pools traffic and so on and so forth. But it was at the cost of another experience, which might have been another system of hierarchy. That to me is very interesting, and where the work of the two firms intersect: it’s all about establishing hierarchy and making choices on the basis of a particular set of assumptions or values.

Karen Stein, architectural consultant and writer: In your work, Jorge and Gabriela, in some way you’re seeking resolution in the project — ultimately you’re making a building for a client that has to serve some function. Whereas, Neri, you’re actually hoping to not have resolution. The appeal is that we don’t know what the resolution is, or that there might not be one. Or there might be three hundred. And therefore the space that it operates in is very different.

Cara McCarty, Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum: One of the buzzwords in the United States these days is “innovation.” I can see for you, Neri, and your students, that that’s what drives a place like MIT. But what does innovation mean to you, Jorge and Gabriela? Is that important to you at all?

Ambrosi: We always think of innovation, but we cannot do so without recognizing what has preceded us. We transfer concepts and ideas of previous architects, Mexican or others, and take them from one point to another. This is our task; we embrace it and don’t want to shy away from it. We can’t think that we are here just to innovate.

There’s a huge legacy behind us that has given us this opportunity. We understand that we’re just a small piece in an evolving tradition. We see in Mexico some people that approach innovation as a way to erase everything and start from zero. And that’s not fair — we all have fathers and without them we cannot be here. You have to recognize that, and from that point you can transition to another.

The DAR Building by AMBROSI | ETCHEGARAY | Photo by Luis Gordoa

We recently made a trip to Japan, and we understand that Japan has come to this point of realization in their architecture. Their architects understand perfectly where they come from, and they achieve this translation of heritage and knowledge into a contemporary world. For us it was a very impressive culture. So innovation for us is more the courage to embrace what you are and take it from that point to wherever you want. It doesn’t matter how large the step.

Yesterday, we were at a Boston Celtics match, and it was the first time that I was in a stadium in America. It’s completely different than how we developed our stadiums in Mexico City. And I realized that American culture has a very powerful way to embrace what it is. And that surprised me. As Mexicans, we’re more ashamed of who we are. That’s why United States is where it is — you have this possibility to embrace who you are, and you don’t feel ashamed of everything that precedes you. We have to look at the paths our ancestors made as red carpets to this age.

McCarty: That’s a good answer. Very beautiful.

Jonathan Marvel, Marvel Architects: I have a question about geometry, the fundamental tool or guideline for what we do as architects. You both presented two very different kinds of geometry. Gabriela and Jorge, you showed geometry reminiscent of Palladio or Brunelleschi’s Ospedale degli Innocenti. Neri, you presented fractal geometry. So we have two extremes: Renaissance geometry, in which almost everything in your projects is at a 90-degree angle, and organically derived, mathematically extrapolated geometry. What I’d like to know is, what are your organizing or guiding principles for geometry? Do you consciously operate with geometry or are you going along with your systems intuitively?

Cartesian Wax, from the Material Ecology project, designed by Neri Oxman | Photo by Mikey Siegel, courtesy of Mediated Matter

Oxman: Subconsciously. Is that a good answer? It’s a one-word answer.

Euclidean geometry proceeds logically from axioms to three-dimensional space. It is hierarchical, logical, and structural. If you add time in you get Newtonian physics, forming a single space-time continuum. Field conditions, on the other hand, are very different because they can contain multiple dimensions in addition to space and time, like material or environmental properties. They are often non-hierarchical and challenging to represent. But they are also incredibly promising if one can actually translate forces into matter, and matter into structure, and so on. When you design with fields rather than with points, lines, surfaces or solids, you are working with continuums of physical properties that grade over space and time. This kind of modus operandi lends itself to a different kind of aesthetics, and not only one that is visual or physical, but one that is also intellectual, of the mind.

Etchegaray: For us, as Jorge was saying, the geometry responds to what the materials can achieve. We have always said that architecture is built by men, and that nature is “natural” — we have never tried to compete with it or to copy its shapes, patterns, or formal complexity. We do our work, and we try learn from nature, but we don’t bring that complexity and diversity to architecture. The geometry that we love exploring or designing is the result of what the materials are and can become.

Ambrosi: I think we design for the hand that’s going to build what we’re thinking. It’s very different to design something that a computer or mechanical hand is going to build. We’re designing for the hand of a person that has minimal education, and what he can do is put a brick on top of a brick. It’s primal, very basic. Earlier on we were developing or exploring different kinds of materials and different ways of assembling these materials, but we realized that we don’t have the hands to build them. And I have seen in Latin America that most of the architecture that has these organic forms in the end looks horrible.

Selldorf: You talk about materials, but materials, as far as I’m concerned, are closely linked to making things, which also includes education, craft, and heritage. How do you translate this making of things into the next generation of making to provide a different kind of intelligence?

Front view of the completed Silk Pavilion in the MIT Media Lab Lobby | Photo by Steven Keating, courtesy of Mediated Matter

Oxman: By using technology to provide stronger more meaningful connections with nature, by forming a new kind of craft. This goes back to what you said, Jorge, about the silkworms being primitive. The silkworms deposit the silk in a figure-eight motion, forming infinity signs. It is curious how at once efficient and poetic, sophisticated and primitive biology can be, not unlike craft. That such expressions of organizing non-woven silk create highly complex structures using very simple rules is true for both worlds — craft and biology, culture and nature. And by generating simple rules in intelligent ways, you can create structures that are incredibly detailed, complex, multi-functional, and materially sophisticated as can be seen in Isfahan, the pyramids, or in the silkworm’s cocoon. It’s all the same to me and I don’t distinguish between these categories. I was looking for places where our practices share an affinity. This kind of thinking points perhaps towards ideological resemblance, the ultimate unity between nature and culture — like worms in mezcal.

Jorge Ambrosi and Gabriela Etchegaray are principals of Mexico City-based AMBROSI | ETCHEGARAY. Neri Oxman is the founder and director of the Mediated Matter Group at the MIT Media Lab.