Nothing Spectacular

With an ambitious project in southern Florida, Germane Barnes is helping a neighborhood envision a better future.

October 26, 2021

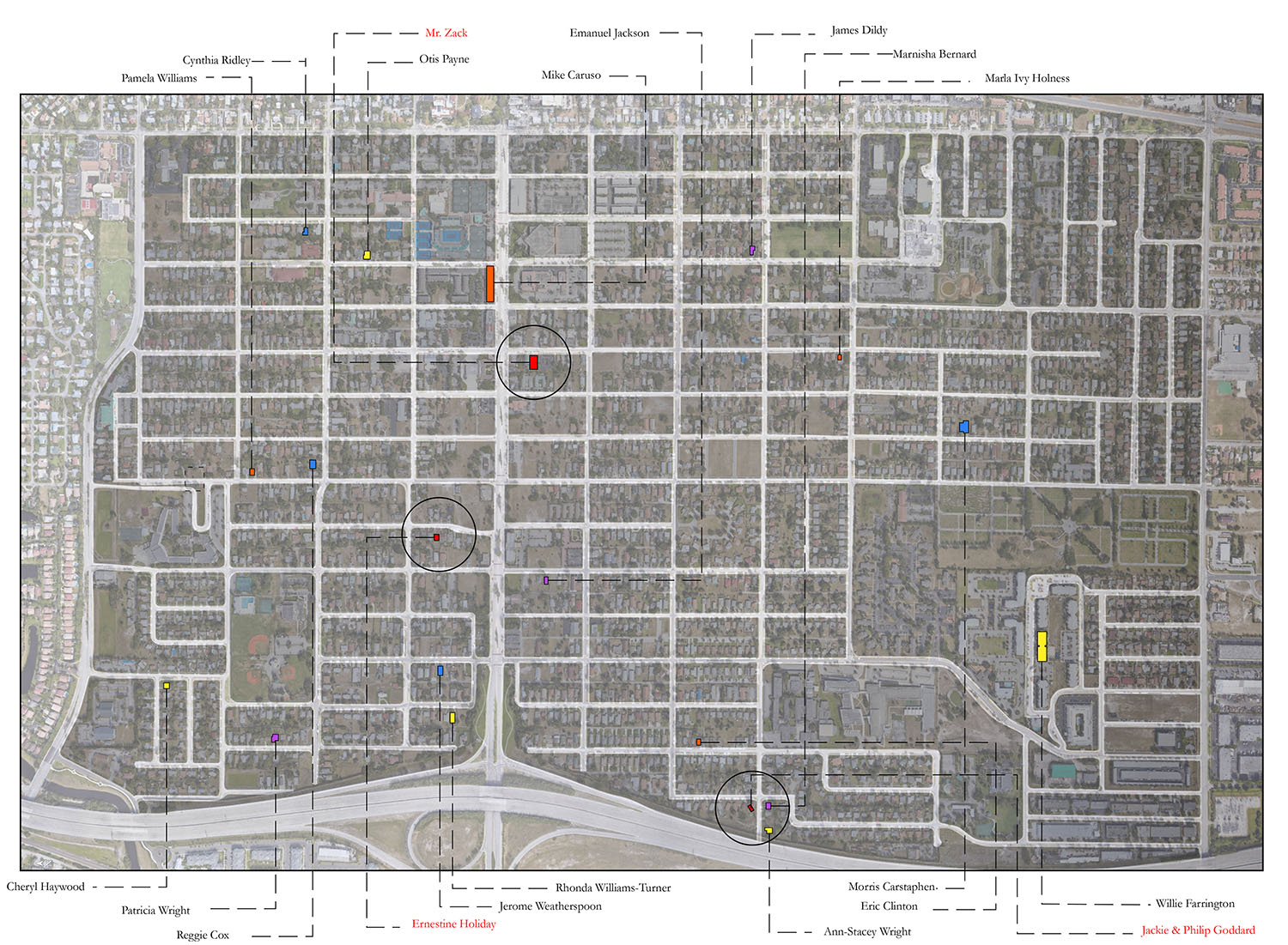

Competition entry for The Set Housing Development, a mixed-use, mixed-income development designed to meet a variety of community needs, from workforce development to healthy food, in Delray Beach, Florida. Collaborators on the design included Germane Barnes, Jennifer Lamy, RLC Architects, Kayne Capital, Covelli Design, Kaufman Lynn, THRIVE Delray, and the Delray Beach Housing Authority. Image credit: Germane Barnes

For the past four years, Germane Barnes has been collaborating with a nonprofit developer on a large-scale project in Delray Beach, a small city in southeast Florida. Focusing on a historically Black neighborhood called The Set, the initiative aims to revitalize the district by improving the existing building stock and adding new amenities without triggering gentrification and displacement.

The League’s Anne Carlisle and Sarah Wesseler spoke with Barnes about the project.

*

Anne Carlisle: You’ve spoken about legacy preservation and how it differs from historic preservation. How do you think about that distinction in the context of Delray Beach?

Germane Barnes: In school, we’re given this idealistic view of architecture. But when you begin to unlearn the systems within architecture that remove culpability, you begin to see how corrupt the profession can be.

One of those systems is historic preservation. Once you understand the legal process and language that are required for something to be historically designated in the United States, you realize that this process doesn’t really see much value in a lot of Black communities. Oftentimes the things that make spaces interesting or of historical significance in our communities is what happened within them, not their architectural character.

A good example is the Black Panther’s headquarters building. It’s an empty parking lot for a Walgreens now, because it was just a regular Chicago two-flat building. It would never have been given a historic designation for its architectural qualities, but that’s one of the most historic places in the entire city because of what Fred Hampton stood for as a Black Panther.

So with the Delray Beach proposal, there was less emphasis on historic preservation, because there isn’t much that’s architecturally interesting about the housing typologies in the area.

The neighborhood where we’re working, the West Settler’s District, or The Set, was next to a sundown district—meaning that once the sun set, no Black people were allowed in the area. Residents found safety in the Set. The legacy that neighborhood holds is important because it was a place where people could be safe, they could hang out, they could enjoy themselves. In homeownership, they could claim a sense of purpose, a sense of identity. So that collection of standard-issue Florida homes is something you want to keep, or else you lose a lot of that history.

A lot of my work is about taking things that are important to us in the Black community and finding a way to keep them, as opposed to having them be destroyed or forgotten.

A Spectrum of Blackness, Germane Barnes's contribution to MoMA exhibition Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America, explores what it means to be Black in Miami, Florida. Credit: Germane Barnes

Carlisle: The Delray Beach project is extremely sprawling and ambitious; you’ve worked on everything from church renovations to massive housing developments. How did you initially become involved in the project? How do you describe its scope?

Barnes: I got involved when I was approached by Sara Selznick and Kristyn Cox, the cofounders of THRIVE Collective, which is a nonprofit developer working in Delray Beach, back in May of 2017. Sara saw what we had built in Opa-Locka—the farm, the park, and the arts and recreation center—and said, “Hey, we have a similar area in Broward County. Would you be interested in trying to implement some of those same initiatives here?” Like the Opa-Locka project, they’re also working with grassroots organizing and community-oriented human design.

Before and after images from Studio Barnes's multi-site Made in Opa-locka initiative. Credit: Germane Barnes

The overall goal is community redevelopment that’s centered around the user as opposed to the developer—where the assets are created in collaboration with local stakeholders who are typically left out of these kinds of projects. Usually, the developer comes in and says, “Let’s do this and be done with it.” This project is asking, what if the individuals who live in this community use their own political capital and put forward the proposal for what gets built? Ultimately, the goal is to help a neighborhood envision a better version of itself.

The main difference between Delray and Opa-Locka is homeownership; individuals still own a lot of their property in Delray. But there’s a clear divide between the Black side of town and the white side of town, especially in terms of a disproportionate allocation of resources.

My first collaboration with THRIVE was the Pop-Up Porch. Sara saw some of the research I was doing around the porch and asked how much I thought it would cost to build something as an activation for some of the unused parcels of land in the neighborhood. Now that project is deployed throughout Delray Beach whenever they have events.

In 2019, after we finished the Pop-Up Porch, we applied for a grant for the Front Porch Project. We got $50,000, and with that money we started to do home improvements for five houses in the area, specifically the residences of block captains. Block captains are simply people who really care for their neighborhood and are actively involved, going to meetings in the city, doing things to make it better. We said, “Hey, we’ll help renovate your porches,” or just fix any damage. Nothing spectacular, but it’s a space that all these people use, so why not try to try to make it as good as it possibly can be?

That branches into the larger idea of my whole practice: I take everyday things that others take for granted and bring them into the larger zeitgeist. There’s nothing special about the front porch, but sometimes it’s all we have. When things like Jim Crow laws prevent you from going other places, or when you just don’t have safe areas to go to, you’re relegated to this small plot of land.

Once we finished the Pop-Up Porch, THRIVE told us about the churches they’re working with. They asked us to figure out some way to create a destination where people can go without needing to leave their neighborhood, and to create resources that generate revenue for the churches.

One of the things you learn working with Black churches is that typically they want to build a bigger church. Then I think, “Yeah, but your congregation isn’t that large now, so why would you want to have more sunk costs?” Their second priority is housing, but always senior housing, because that’s who their parishioners are.

Part of my goal with this project is to show them what other types of community assets they can implement with the resources they already have—and how they can bring in the younger demographic that they’re clamoring for, but that they haven’t created the infrastructure to attract.

Carlisle: What are you doing with the churches to help them leverage their assets and reach those goals?

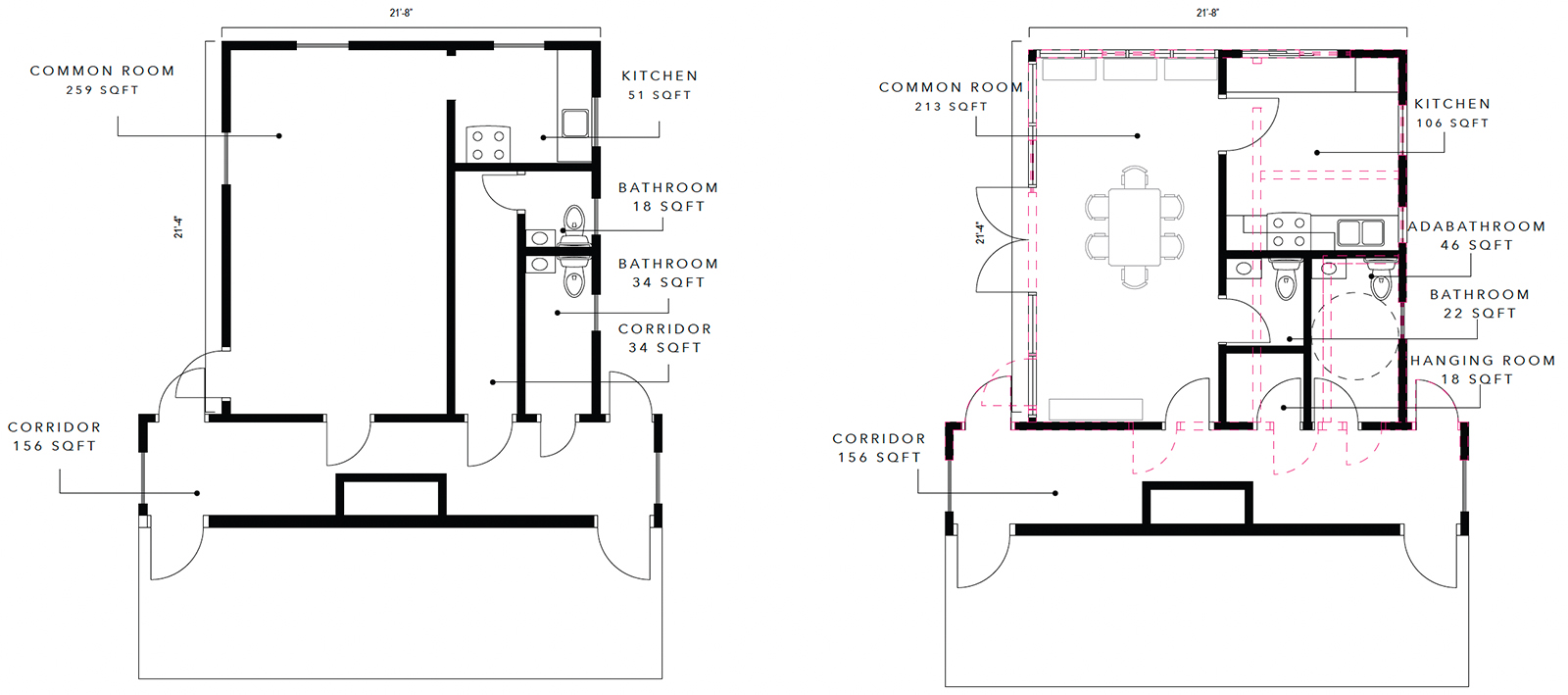

Barnes: We’re working with three churches. What we’re asking is, how can we utilize what each church already has, making sure that each one of them has its own separate programming and doesn’t overlap with the others?

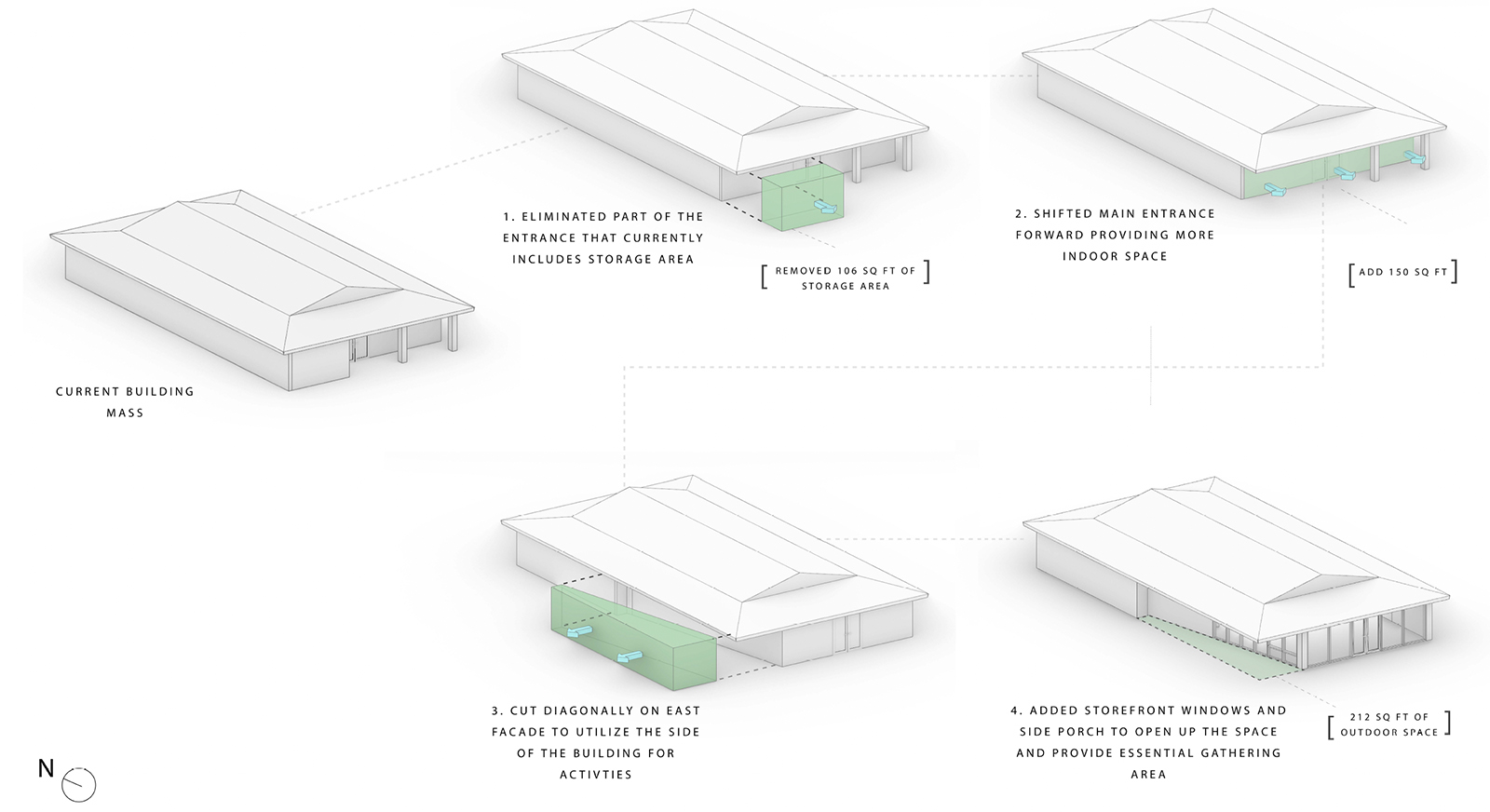

For example, one of the churches does cool food giveaways on the weekends. They were using a very small room for this, so we proposed renovating it to make an area where they could have pop-up cafes. There are a lot of chefs in the area that can’t afford a storefront, so they do pop-ups out of their garages. We said, what if the church could host these chefs as a way to bring a new set of people into the congregation?

Carlisle: What’s next for the Delray Beach project? Where do you think it might go in the future?

Barnes: One of the first things I collaborated on with THRIVE was a proposal for a big redevelopment plan for Atlantic Avenue. For various reasons, our proposal did not win. But we still want to find a way to implement some of the ideas we developed.

We’ve been talking about taking a shotgun home, which is a typical historical housing typology in the area, and breaking it down into a play structure. The trusses will be exposed; there will be rock climbing. It’s a multidimensional, clear reference to the history and the architectural language of the area. Future generations can play on it while learning about their heritage.

We’re also thinking about townhouses. We realized didn’t make sense to put all the housing that’s needed in one massive multifamily development; there are different types of families in the area, which might not work well in a multi-income apartment complex. Single people may not want to live next to a family with four or five kids. But can we offer another residential typology that can accommodate different kinds of households.

Kristyn Cox and Sara Selznick, the women who run THRIVE, are amazing. They know everyone in Delray Beach on a first-name basis and are the ones making all this stuff happen.

For me, these projects are successful if they get built; they’re extremely successful, selfishly, if they’re built the way that I would like them to be built. With these types of projects, it’s rarely the second; it’s typically the first. But it seems like the architecture world is beginning to understand the importance of the aesthetic when it’s placed in the context of the community. It’s like, “Hey, I know this probably isn’t going to be the most exciting building in the world, but it does a hell of a lot more for the people who live here than that empty monument three blocks away.”

But as an architect working on community-driven projects, there’s always a tug and pull between aesthetics, what people in the area want, and what the budget will allow. In the perfect situation, you get that client with deep pockets that says you can fulfill your own desires within the project as well as the communities. Thanks to THRIVE, I think the Delray Beach work is one of those projects where that’s actually possible. For example, in one of the churches we proposed slicing part of the building off into a curtain wall system to open up the space and make it more interesting. THRIVE said, “Oh, we absolutely love that,” when they could’ve said, “That seems expensive. That’s not going to happen.” So now we just need the community to say, “Oh, that looks really interesting; we’re okay with that being a part of the project.”

Carlisle: Community involvement is the core of this project. What has your experience working with the community been like?

Barnes: When you’re doing community-oriented design, and especially with an older demographic, you have to convince them why their way isn’t the only way. And that’s difficult, because if you’re a 70-, 80-year-old Black woman or Black man, you’ve seen a lot in this country—you’ve seen a lot. You were not integrated when you were going to school. You might have experienced the Jim Crow South. You might have been a part of the Great Migration from the South up north. So they hear someone that could be their great-grandkid saying, “No, you don’t need more senior housing. What if we did this instead?” and it’s like, “Kid, shut up.” I’m not kidding! [laughs] Or they’ll say, “Look, you’re adorable, but we know what we need.”

What I’ve learned is, I have to get them to understand what I’m doing, I say, “You worked so hard to get to where my generation can have a better chance than yours had. And you sent us to the schools that you all couldn’t go to because of legal segregation. I’ve got that education you wanted me to get; I’ve got the job you wanted me to have. So let me show you things that I’ve learned that you’ve literally given your blood, sweat, and tears for. And if you don’t do that, why did you make me go to those places?”

When you frame it like that, they say, “You know what, okay, I’ll take a step back. I’ll allow you to do the thing you’re doing.” Otherwise, you’re always fighting that battle.

The other challenge when you’re dealing with older folks is figuring out how to educate without ageism—without implying that they can’t learn new things. That’s something I had to get out of my own mind: the idea that they’re not going to believe me when I tell them something. But when you package things on their terms, it’s like, “It’s okay, I get it. I understand.”

But it’s still hard to convince somebody that changing a building material or exposing some beams or something can have a positive impact when they’re saying, “We just need housing for the elderly people.” They know that these problems still haven’t gone away.

Sarah Wesseler: So people from the community have strong opinions about the program that’s needed. I’m wondering if they also have strong opinions about aesthetics?

Barnes: Yes. More often than not within Black communities, modest is more. There’s always this desire for modesty, modesty, modesty. And I think that’s because a lot of these communities are so used to having scraps, to put it plainly. When you don’t have monumental cultural institutions in your immediate vicinity, you’re not sure what you can have, and you’re not sure what you deserve. So a lot of times if you come in and you say, “Hey, let’s put in a bunch of glass,” the first thought is, “Oh, somebody can break into there,” or “How do we secure it?” It’s always the worst-case scenario.

You have to learn how to not take those things personally, because it’s not personal. It’s just that for them, whenever they have something nice, it’s always destroyed. That’s part of the reason that when you have a couch it’s clad in plastic, because it’s like, “You know how hard I worked to afford that furniture? You can’t sit here. Go on the porch instead.”

Those things find their way into built work as well. Because people in neighborhoods like this are used to modesty, a museum might just be a regular box with a couple of windows that could easily be a YMCA one day or a Wendy’s the next. But if you propose something that’s just a little more sculptural, it’s typically met with a bit of apprehension. That’s when money always comes up: “Ah, that’s too expensive. I don’t know if we can afford that.”

Then the question becomes, how do we decide what’s worth spending money on? Because if the choice is between spending more money on those elements or helping to fund needed social programs, you have to ask yourself, is it more important to put in glass blocks or to make sure seniors have housing? So if you can get that rare developer who says, “I believe in both of these things and will pay for them,” you’ve hit the jackpot.

The Pop-Up Porch cost $25,000. When I first told the neighborhood, they were like, “Why would we spend $25,000 on that?” And I said, “Well, you don’t have to spend $25,000. That’s the catch. It’s not your money that’s being spent.” And then it was like, “But we could spend that on what we need.” And I said, “You’re going to use it. Watch.” And then they started using it and it was like, “Okay, Germane, you got that one. So what are you gonna do next?”

You need to show some proof of concept. It was the same way in Opa-Locka. When we did the first park there, people said, “All right, I guess I believe you.” And then when we did the farm, they said, “Okay, you’re two for two.” And then when we did the arts and recreation center, they said, “Okay, we won’t bother you anymore.” But it’s a lot of give and take, and it can be extremely frustrating.

It’s fun to glamorize community engagement in academia and publishing because most people aren’t actually doing it. If you’re actually doing this shit, you will get so pissed off. I’m mad all the time [laughs]. Not because of the client, but because of all the procedures, the length of the project, the process you have to go through, the community meetings, the planning board meetings, the politics. It’s infuriating 99 percent of the time because it’s not a straight line path to completion. There are so many hurdles that can be disheartening.

Interview edited and condensed.

Explore

Creating an ecosystem for social design in New Orleans

Colloqate helps architects and laypeople alike understand the potential for a more just, equitable built environment.

Design as civic duty

Elizabeth Timme, co-director of LA-Más, believes that architecture needs to rediscover its political imperative.

Flipping things upside down

In her Not White Walls project, Mira Hasson Henry explores issues of personal expression, cultural identity, and architectural value systems.