Mexico’s Traditional Housing Is Disappearing—and with It, a Way of Life

Mariana Ordóñez Grajales and Onnis Luque are fighting to preserve their country's vernacular architecture.

An interview with COMUNAL: Taller de Arquitectura, one of eight firms honored in the 2018 Emerging Voices competition.

For the past two years, Mexico City design firm COMUNAL has collaborated with photographer Onnis Luque to document the nation’s endangered vernacular housing. The Architectural League’s digital editor, Sarah Wesseler, spoke with Luque and COMUNAL founder Mariana Ordóñez Grajales.

*

How did this project begin?

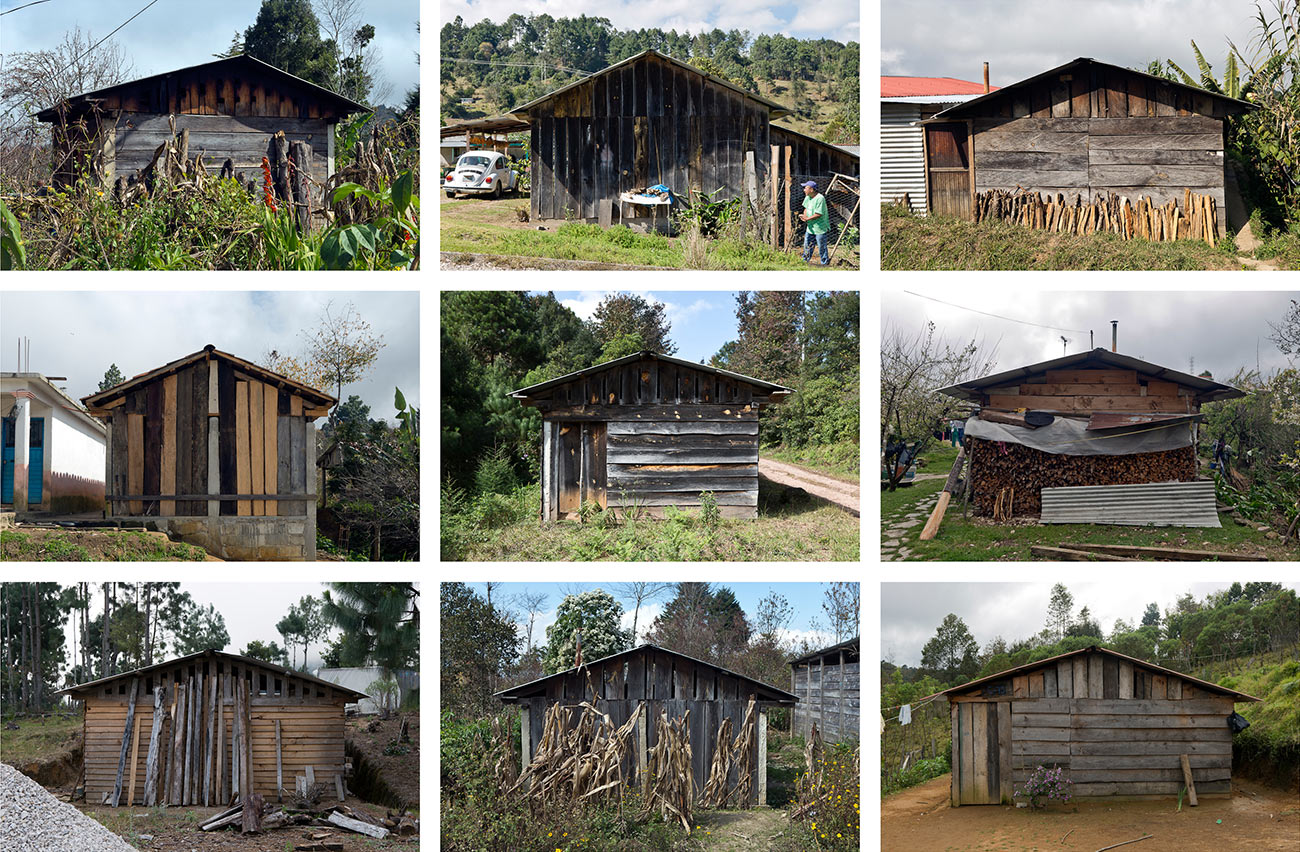

Luque: It started in Yucatan. I went with COMUNAL to do a study of Mayan houses, and we were surprised and amazed by how sophisticated they are—how they relate to the habitat and the land; how the builders perfectly understood the cycles of the environment, the seasons, the types of wood available in the nearby hills.

The traditional vernacular house isn’t separate from its environment. It’s really a part of the territory.

Ordóñez Grajales: But today, issues like migration and urban expansion are causing the loss of traditional typologies, and with them our ancestral building culture.

And government housing policies are contributing to this loss. The current policy says that vernacular housing is unsafe. Well, sure, some specific points could be improved, but that doesn’t mean we should throw away everything the people who have been in this country longest know about architecture and construction.

It’s not easy to find good information about this topic. Valeria Prieto published a book [Vivienda Campesina en Mexico] on Mexican vernacular housing in 1985, but I wasn’t even born when it came out.

We wanted to provide more up-to-date information and conduct a much more rigorous investigation of these typologies. We started to visit communities where we had worked in the past and tried to understand the traditional construction methods.

Luque: The objective is to cover all of Mexico. Right now we have material from the south, some from the north, some from the center, but eventually we’d like to conduct an exhaustive survey of traditional housing.

You’ve written elsewhere that the government’s opposition to traditional housing seems to be partially motivated by a desire to benefit the construction industry. Can you say more?

Ordóñez Grajales: We believe that part of it is an attempt to benefit developers and builders and companies that sell industrial materials.

But on the other hand, there’s a lot of ignorance. A lot of government officials don’t understand how the traditional house functions. They think it’s unsafe because it uses biodegradable materials, but in reality, materials like concrete and steel degrade much more rapidly in some environments.

It’s complex. When government agencies get involved in these issues, they look only at quantitative issues. For example, the government says you have to have a living room, kitchen, and two bedrooms, when the reality is that you can’t divide space like that in rural houses because these big rooms are where people put the harvest, thresh the corn, and dry the coffee. There’s a relationship between the land, agriculture, and living space.

There’s a lot of political laziness. The national housing agency [Comisión Nacional de Vivienda] told us, “We can’t update the measurements that we use to measure poverty or habitable environments. That would cost millions of pesos.” We said, “Go see all the housing projects that you created in rural areas. They’re abandoned [because the people they were built for didn’t like them]. That cost millions of pesos more, no?”

Luque: These policies are particularly perverse because rural vernacular housing is part of a way of life. When politicians impose a building style that doesn’t integrate into the environment, they rupture the social fabric, the local economy, the food system, and create more poverty.

We believe this happens because it’s a way for politicians to maintain control of these regions. These communities have always worked as a group, and when government support arrives, it tends to promote individual production and consumption, not only of housing but of the entire regional economy.

Ordóñez Grajales: For example, right now we’re working in an area that was damaged by earthquakes, in collaboration with an organization called Fundación Haciendas del Mundo Maya. Most of the affected areas are in states with majority-indigenous populations. The politics of reconstruction are focused on [prepaid debit] cards, and the only thing you can do with these cards is buy industrial materials in stores authorized by the government.

We’re working in a community in Oaxaca that’s five hours from the closest urban center. You have to travel five hours to buy cement blocks to build your house. Obviously, the rural communities aren’t the ones benefiting from the sale of these materials.

And the spatial qualities of the traditional materials that they would otherwise use to rebuild their houses are far superior. With the new materials, the houses are smaller and less comfortable.

How have people responded to this project, in Mexico and internationally?

Ordóñez Grajales: There has been interest in publishing the photos, but I think more outside Mexico.

Luque: In Mexico the response has been positive, at least in the architectural community, which recognizes the value of vernacular housing, even if it doesn’t put this recognition into practice.

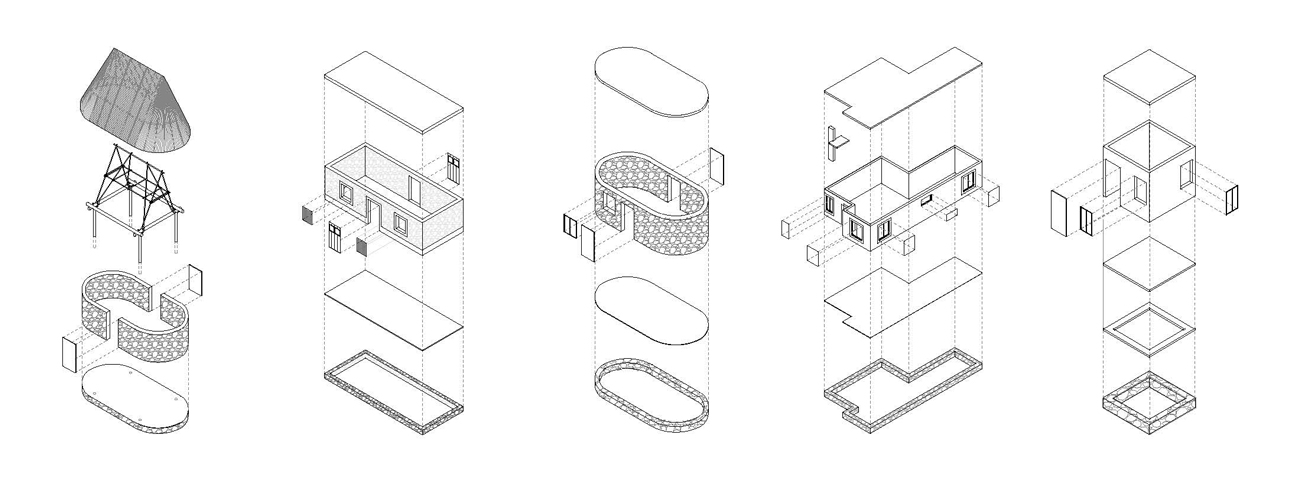

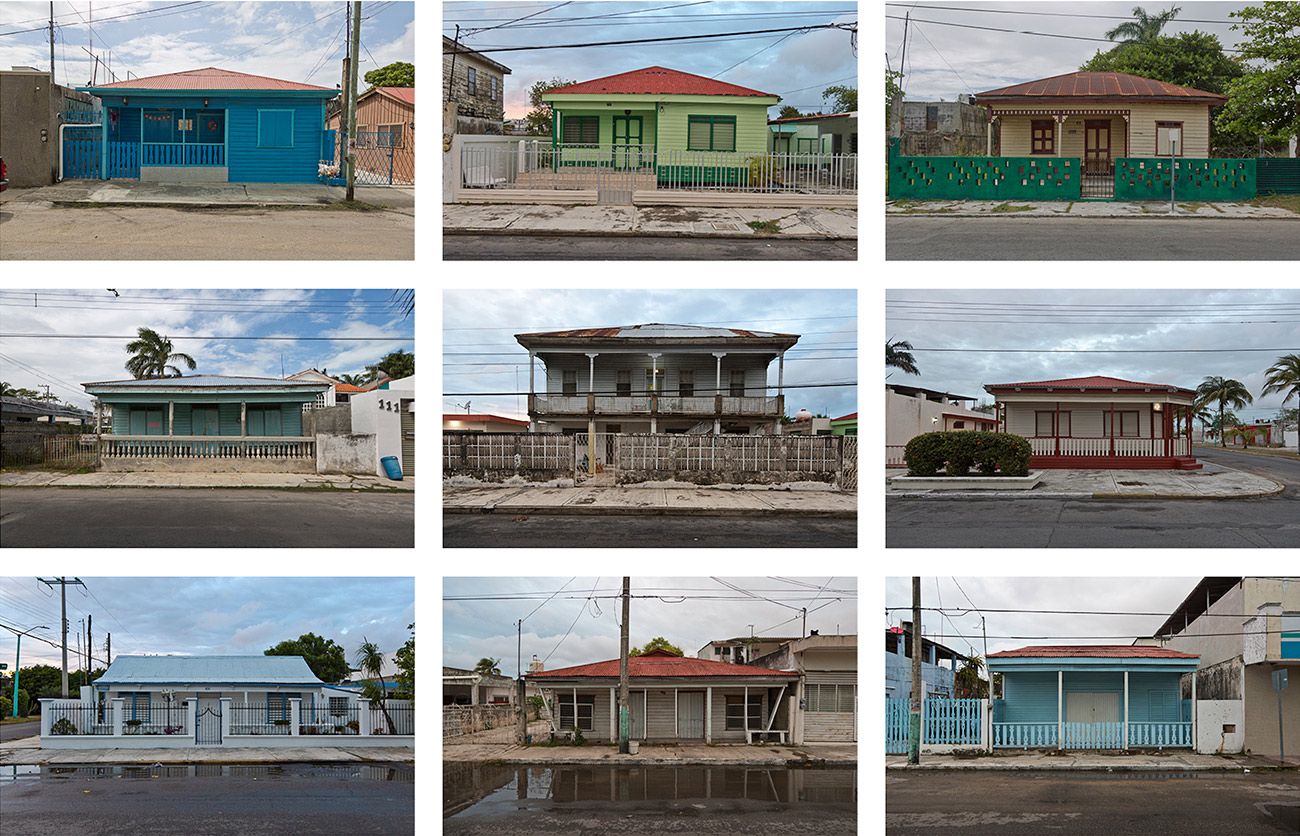

There have been many previous investigations of this theme [in the architectural community], but they’ve been very focused on the Mayan house or other very particular themes. The difference with our project is that we want to include all traditional housing and also show its modifications, because with the passing of time the social dynamics in communities have changed, and this has impacted the way that houses are produced today.

For example, the migration of men from the villages to the United States has resulted in a loss of knowledge—the knowledge that’s transmitted from fathers, grandfathers, to children. This is something that we hope to salvage before it’s lost completely.

Tell me about some of the houses in your photos.

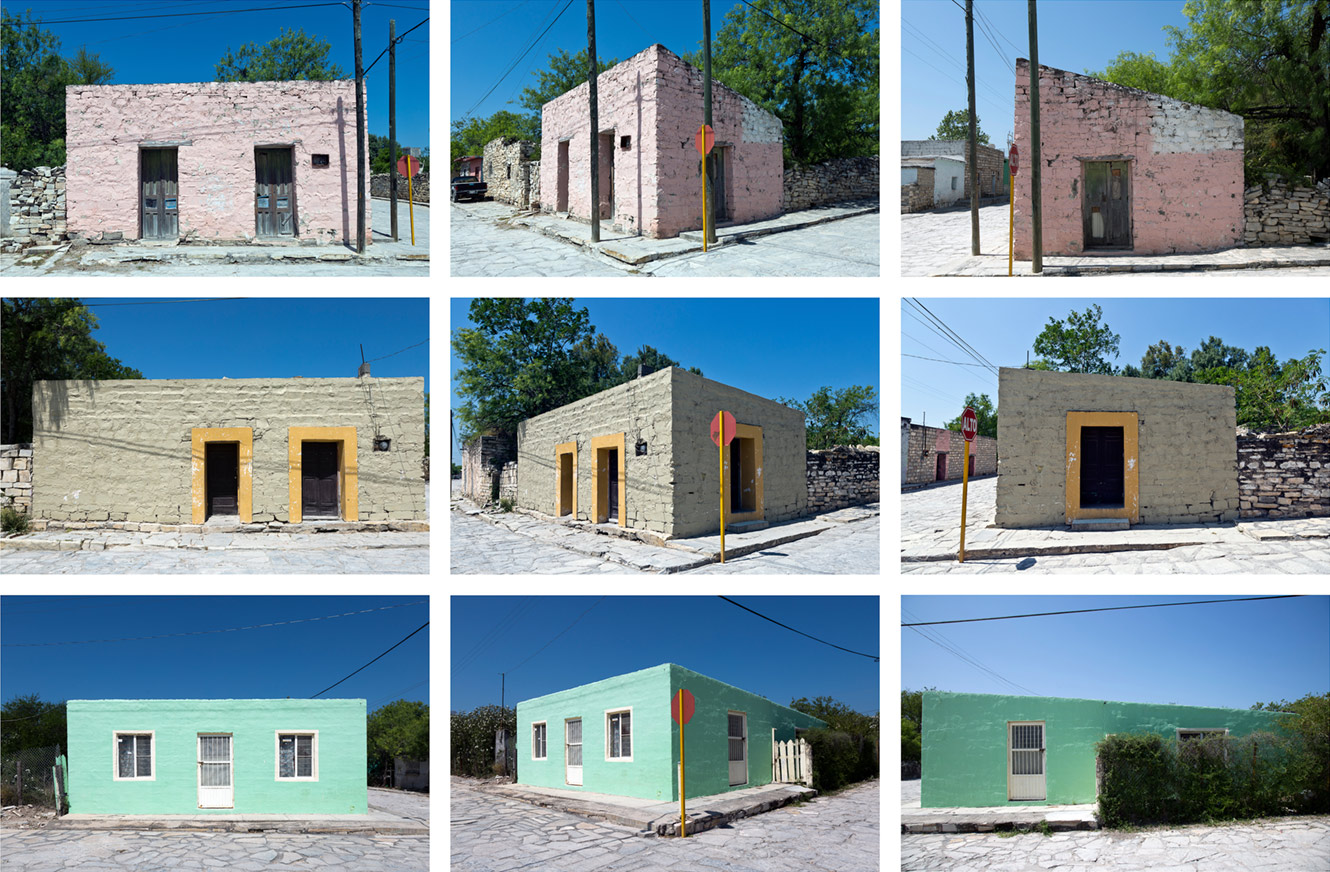

Ordóñez Grajales: One of the “typology mosaics,” as we’re calling them, shows traditional Mayan housing that’s been conserved 100%, and another shows the kinds of transformations that are occurring now.

These changes are occurring for a number of reasons, from social to economic to political. One is that, as Onnis mentioned, generational knowledge is being lost.

Another is that a palm tree used for the thatched roofs is disappearing. Using this material for housing is prohibited, but in the tourist zone around Cancun, all the beach huts at five-star hotels are made with it. So this is putting rural architectural construction in danger.

Another picture shows a house with a man in front. He went to the US and sent back money so he could replace all the stone with concrete block.

Social aspiration plays into this. Today, industrial materials denote that you’re no longer poor. The politics are permeating the communities themselves. The message is that what you can make yourself isn’t good enough.

Luque: It’s ironic, because when we ask villagers which houses are more comfortable, they always say the traditional ones. But the younger generations prefer to live in concrete block houses because of status.

Ordóñez Grajales: One man told us, “Well, I like [traditional houses] better, but in my village if you want to get married you have to have concrete block.” No woman wants to marry you if you’re poor, if you have a traditional house.

Luque: But many people are very proud of their houses and of their own knowledge about them, in spite of these questions of status. They speak about them with a great deal of pride and are very happy that someone is interested in what, for them, is a way of life.

We don’t want to talk about vernacular housing in an abstract way—we want to say that there are people who made this, there’s a person who lives here, there’s a person who puts lots of love and practically his entire life into his home, despite the fact that the government wants to turn the conversation into one about mortgage credits. That’s why for us it’s relevant to have portraits of the owner of the house, or of the family.

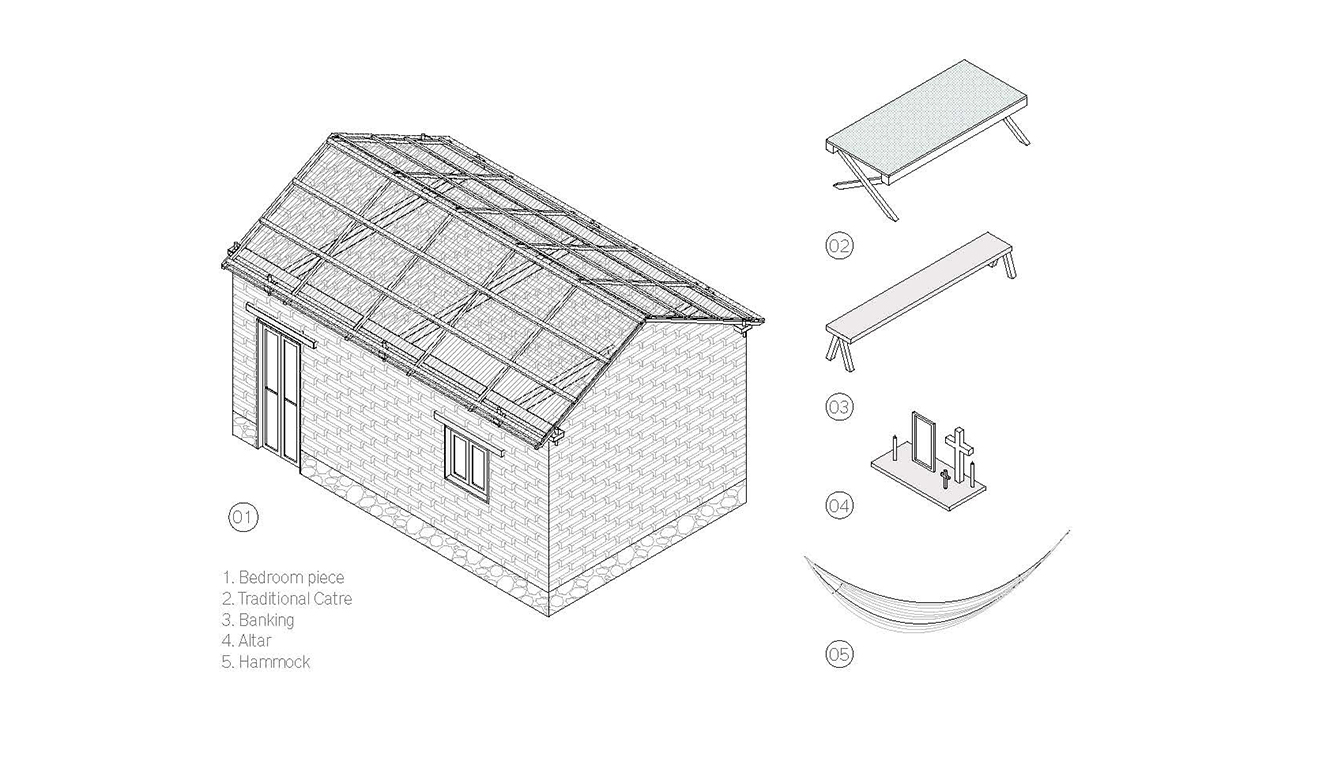

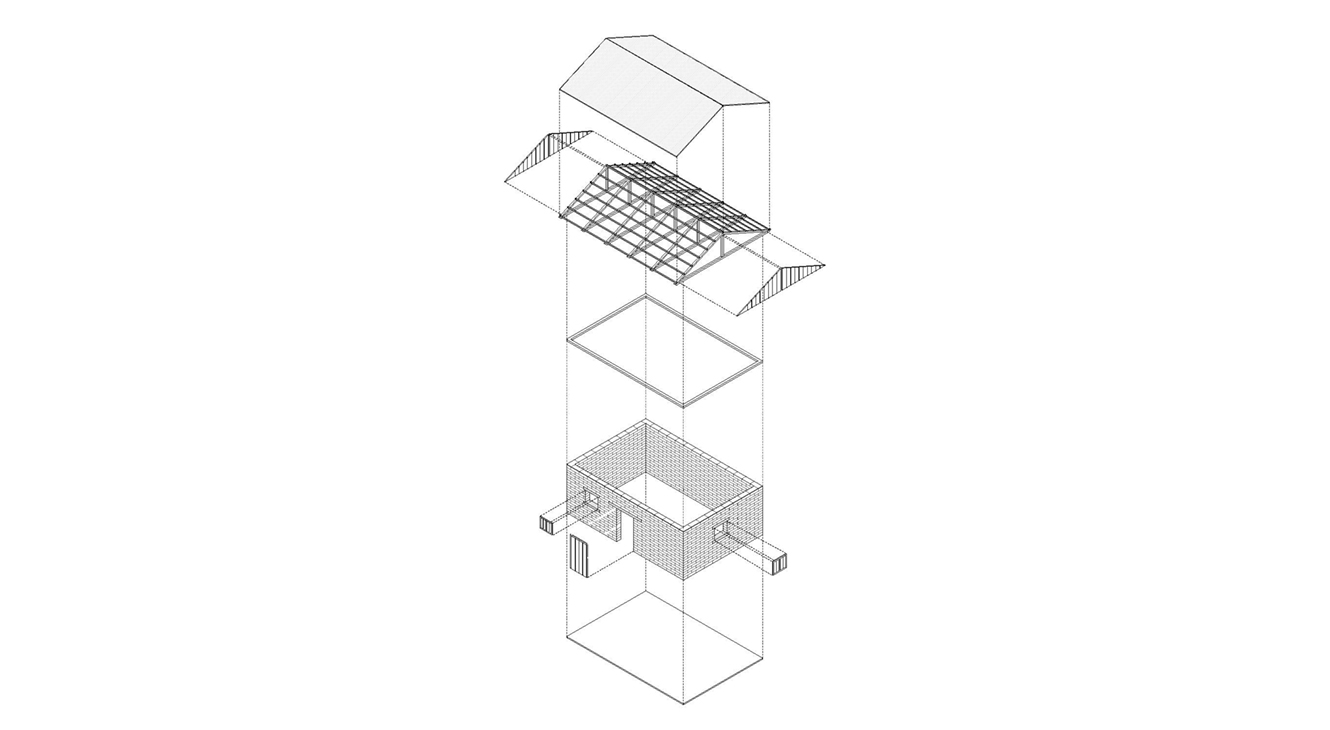

Ordóñez Grajales: We also have images of a reconstruction project that we’re doing in Oaxaca. They show the traditional typology, which is made of adobe block. The earthquake affected these structures badly.

You can see in the images that there are no foundations—the adobe blocks are placed directly on the ground. In the past, their grandparents laid foundations of stone, but extracting the stone takes a long time, and that’s time people can’t spend cultivating corn, beans, other food. So they decided to omit it in order to have more time for agriculture, and because of this they’ve started to have problems with seismicity.

What we’re doing is working to improve the structural system, but without modifying the house in terms of proportions or material or the way space is organized.

This community refused to adopt the construction with the materials the government proposed. They want to conserve their culture, their customs, their traditions. So we’re working with them to develop 150 adobe houses, but this time they’ll be earthquake-resistant.

Ultimately that’s what we want to do: return to a holistic vision of the territory, understanding vernacular housing, and thereby understanding the local climate, the natural phenomena, the soil… that is, absolutely everything.

That’s the marvel, this holistic vision that these original populations had.

Interview edited and condensed.

Explore

The architecture of the Cuban revolution

Josef Asteinza considers the architecture of the Cuban Revolution and its impact on the city of Havana.

Francis Kéré lecture

The Berlin-based, Burkina Faso-born architect discusses his work.

Connective spaces and social capital in Medellín

Jeff Geisinger investigates the built environment's impact on social capital in Colombia's second-largest city.