Proposal | Marble Fairbanks, James Lima Planning + Development, Leah Meisterlin

Marble Fairbanks with James Lima Planning + Development, Leah Meisterlin, and Special Project Office

Karen Fairbanks, Scott Marble, James Lima, Leah Meisterlin, Richard Tyson, Jason Roberts, Keenan Korth, and Dare Brawley

The Marble Fairbanks team was one of five interdisciplinary design teams selected to participate in Re-Envisioning Branch Libraries, a design study organized by the League and the Center for an Urban Future in 2014. Read about their proposal below.

An interdisciplinary team led by Marble Fairbanks Architects with James Lima Planning + Development, Leah Meisterlin, and Special Project Office employed a data-driven approach to strategically plan for libraries as an integral part of a citywide system of public services and resources. Their objective was “to help the libraries position themselves within the network of city infrastructures to make their value more visible,” according to team member Karen Fairbanks. The proposal positions the library at the center of public policy priorities, as an overlooked but vital part of the civic infrastructure critical to achieving a more equitable city.

The launching point for the proposal is re-envisioning the libraries as “one networked system.” That network does not refer to merging the city’s three existing library systems (New York, Brooklyn, and Queens), but to integrating, relating, and placing libraries within the broader civic infrastructure of public resources across the city. With the library at the intersection of a number of crucial public and social services — including education, wellness, skills training, and support for vulnerable populations — the goals for the system can augment the city’s goals for schools, community centers, senior centers, evacuation sites, and more. At every scale, “the library is connected to other needs and other institutions,” explains Fairbanks. “If we plan in relation to the distribution of resources for other infrastructures — and the library is part of thinking that way — everybody’s going to get something from this.”

To allow library and city officials to readily see how library investments can serve a number of different policy priorities, the team created a set of powerful planning tools to aid decision-making at the scale of the building, the neighborhood, and the city.

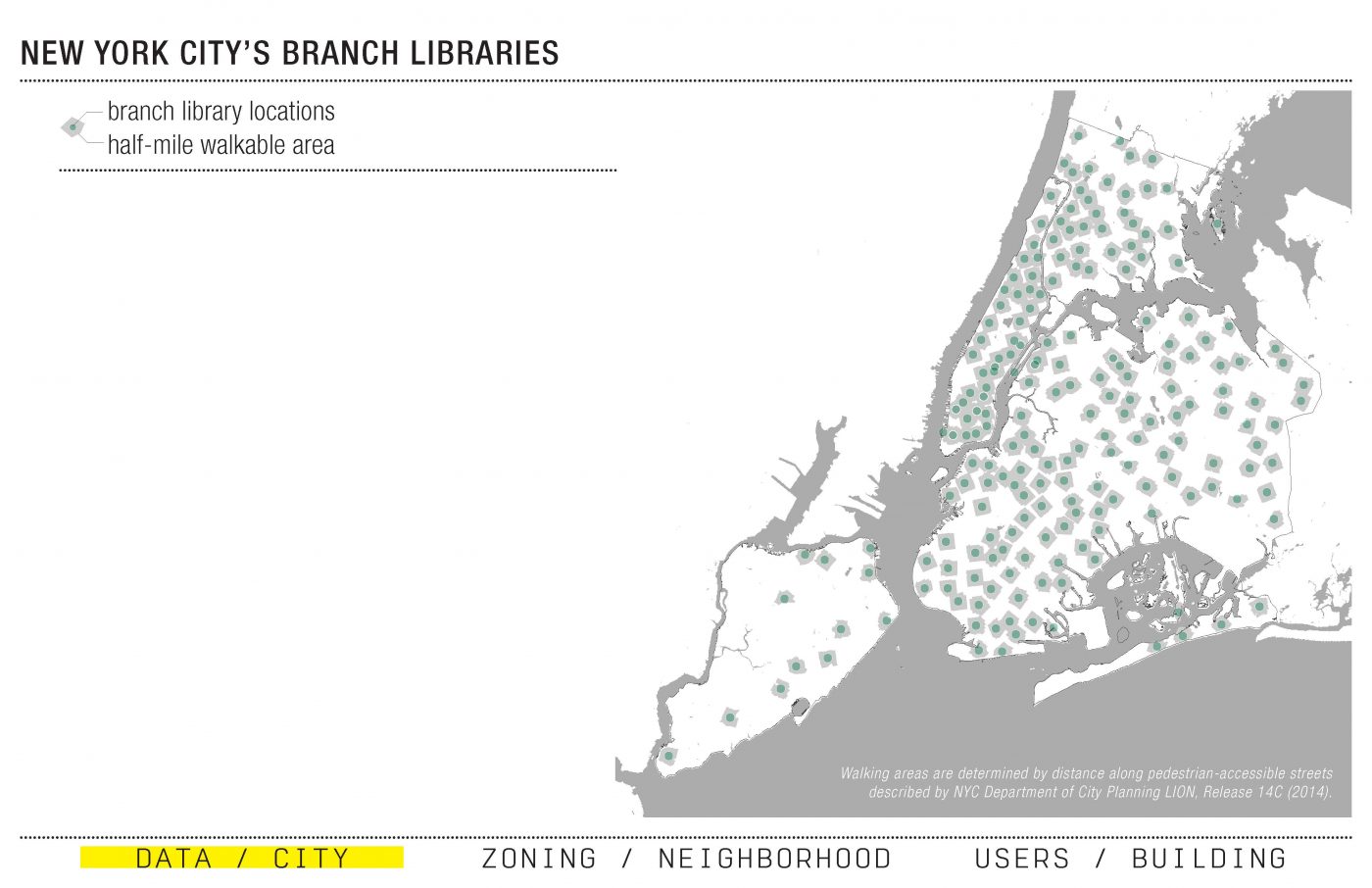

Data // City

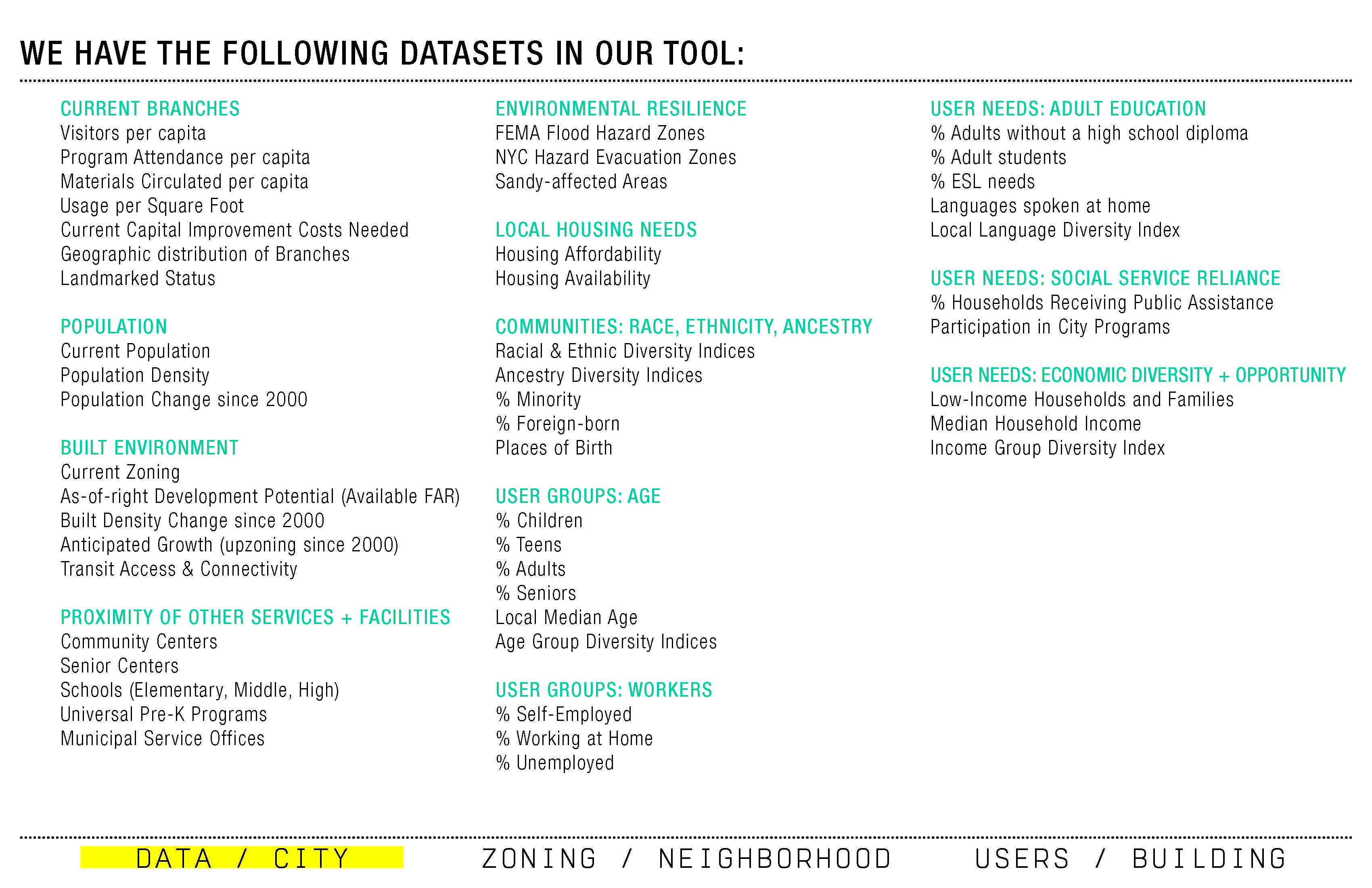

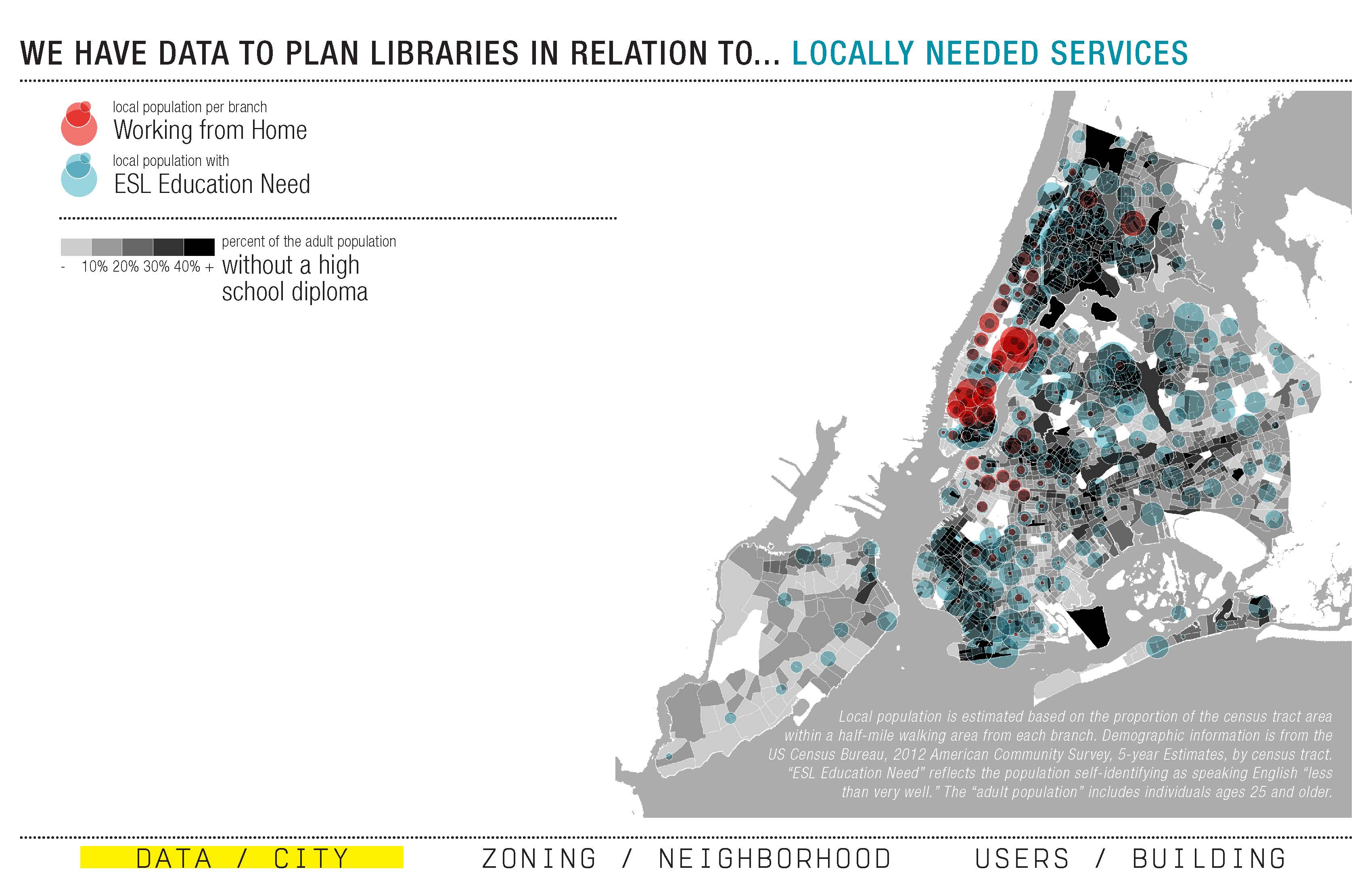

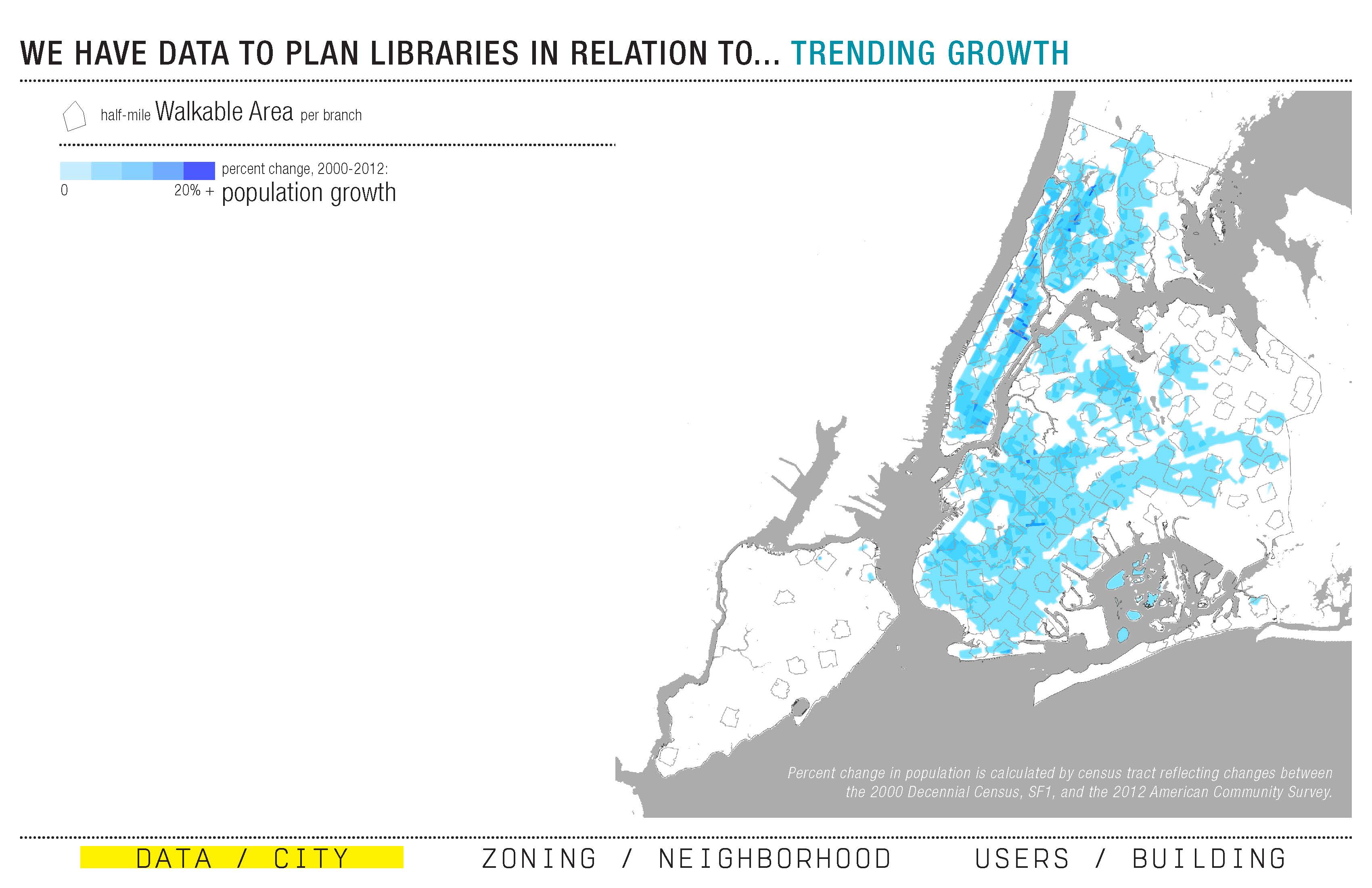

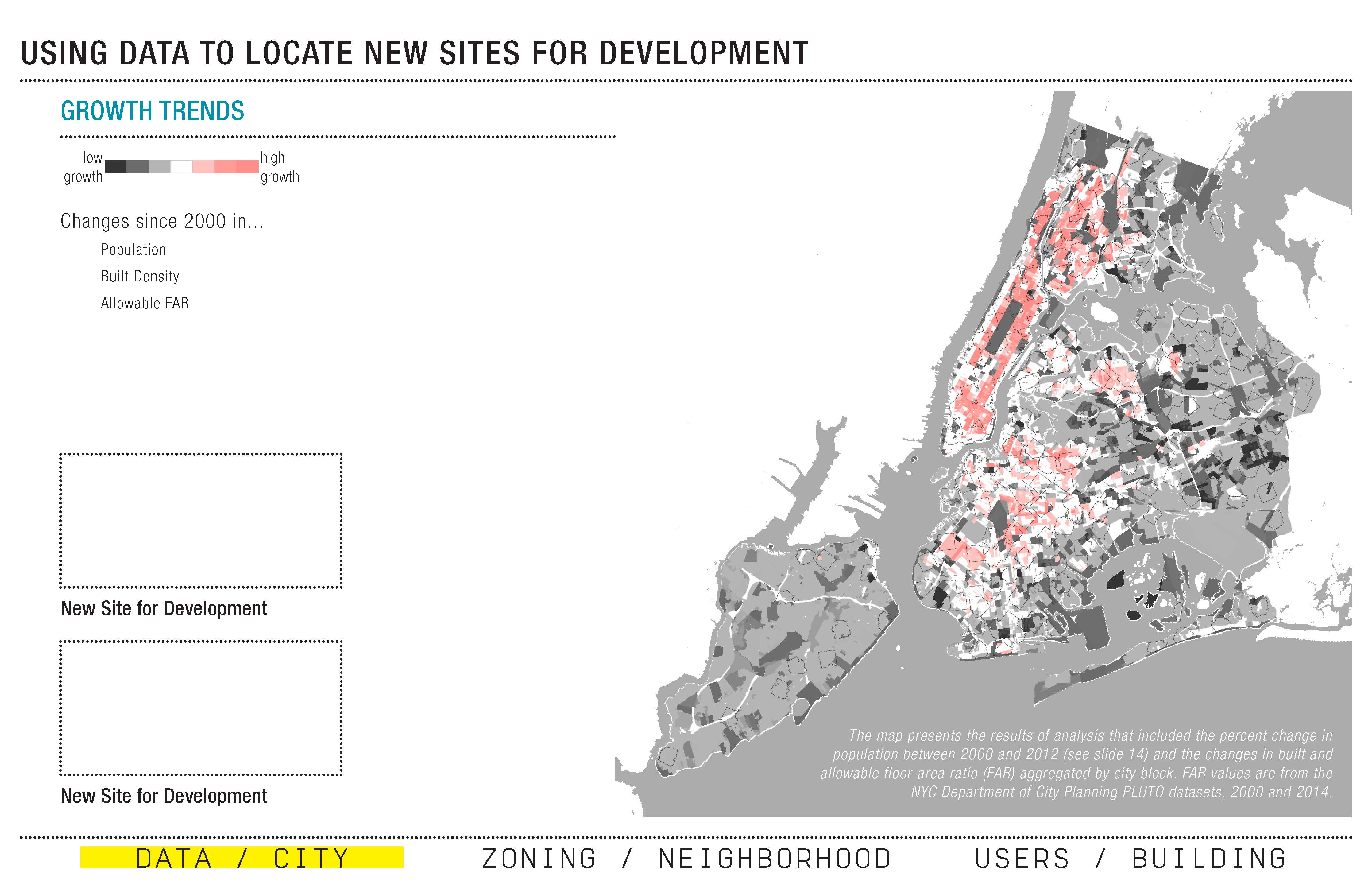

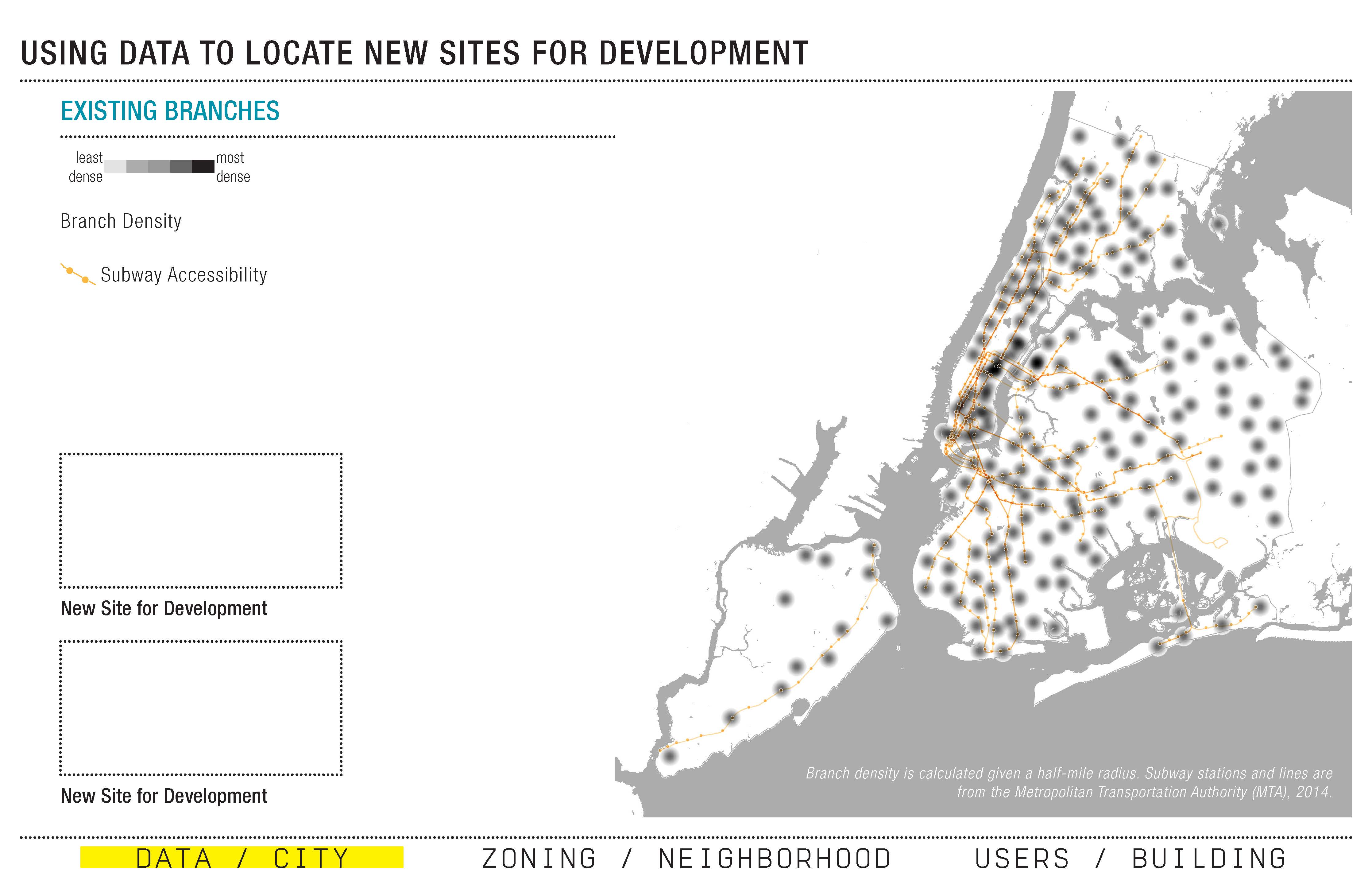

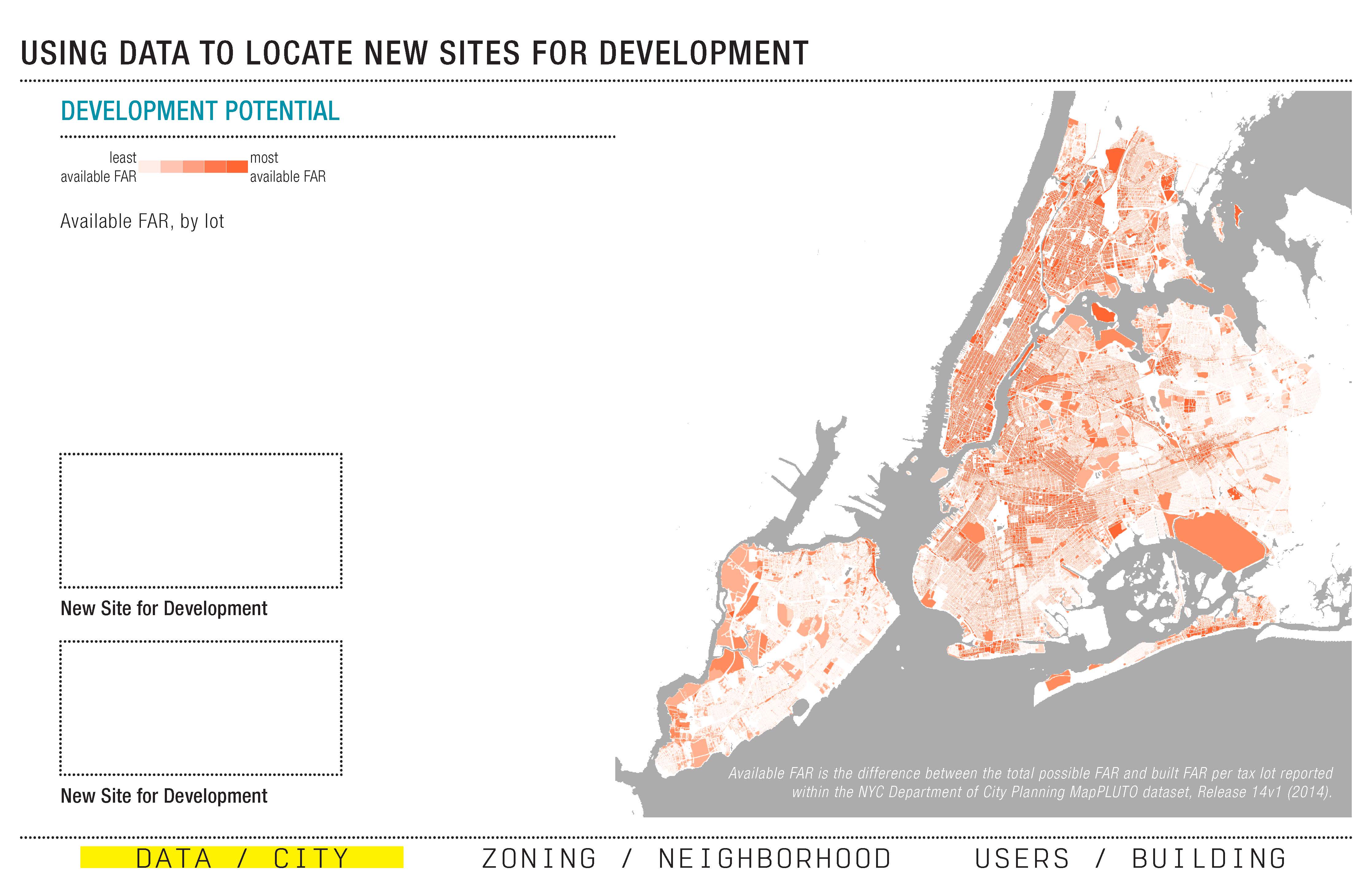

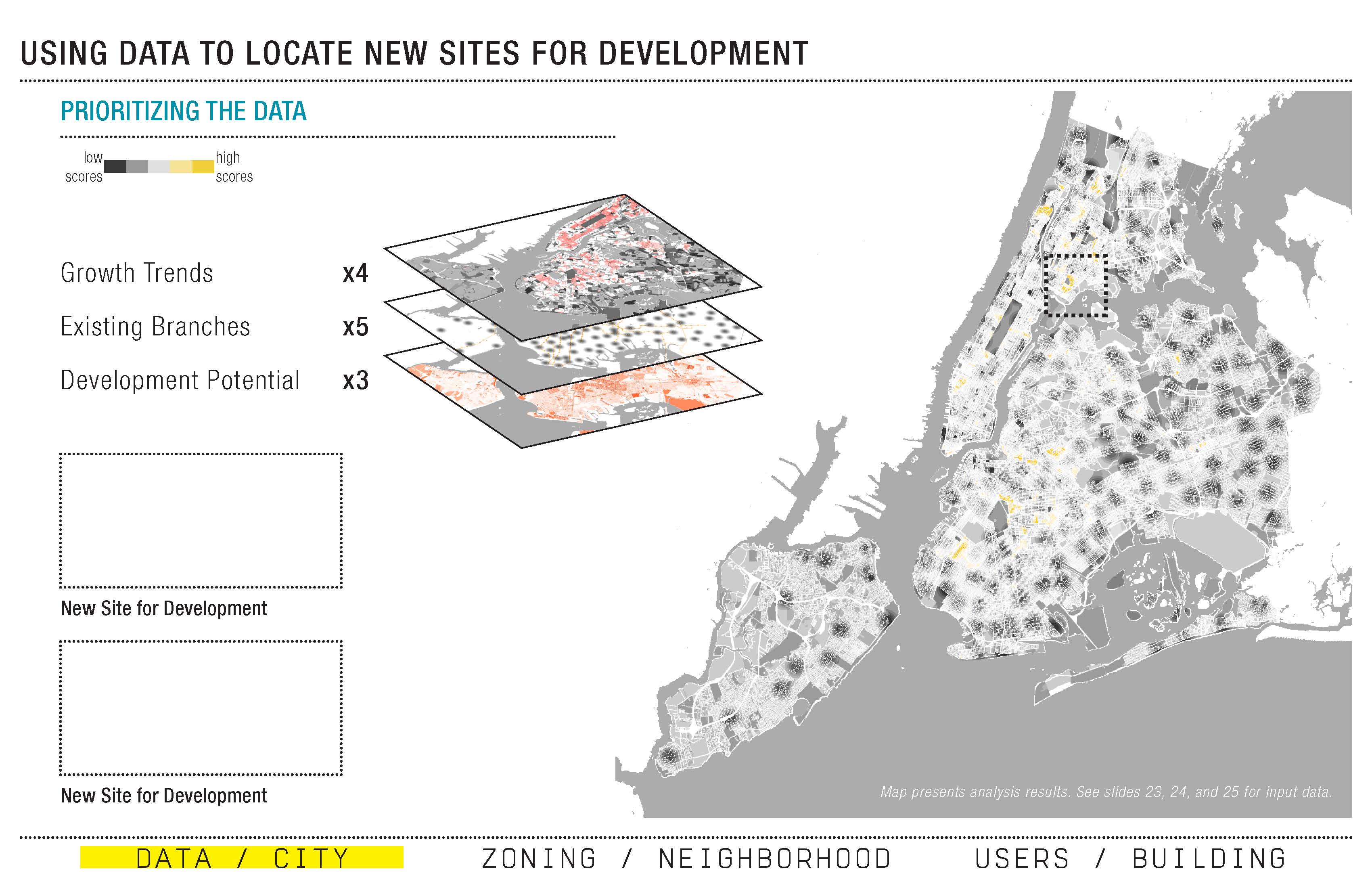

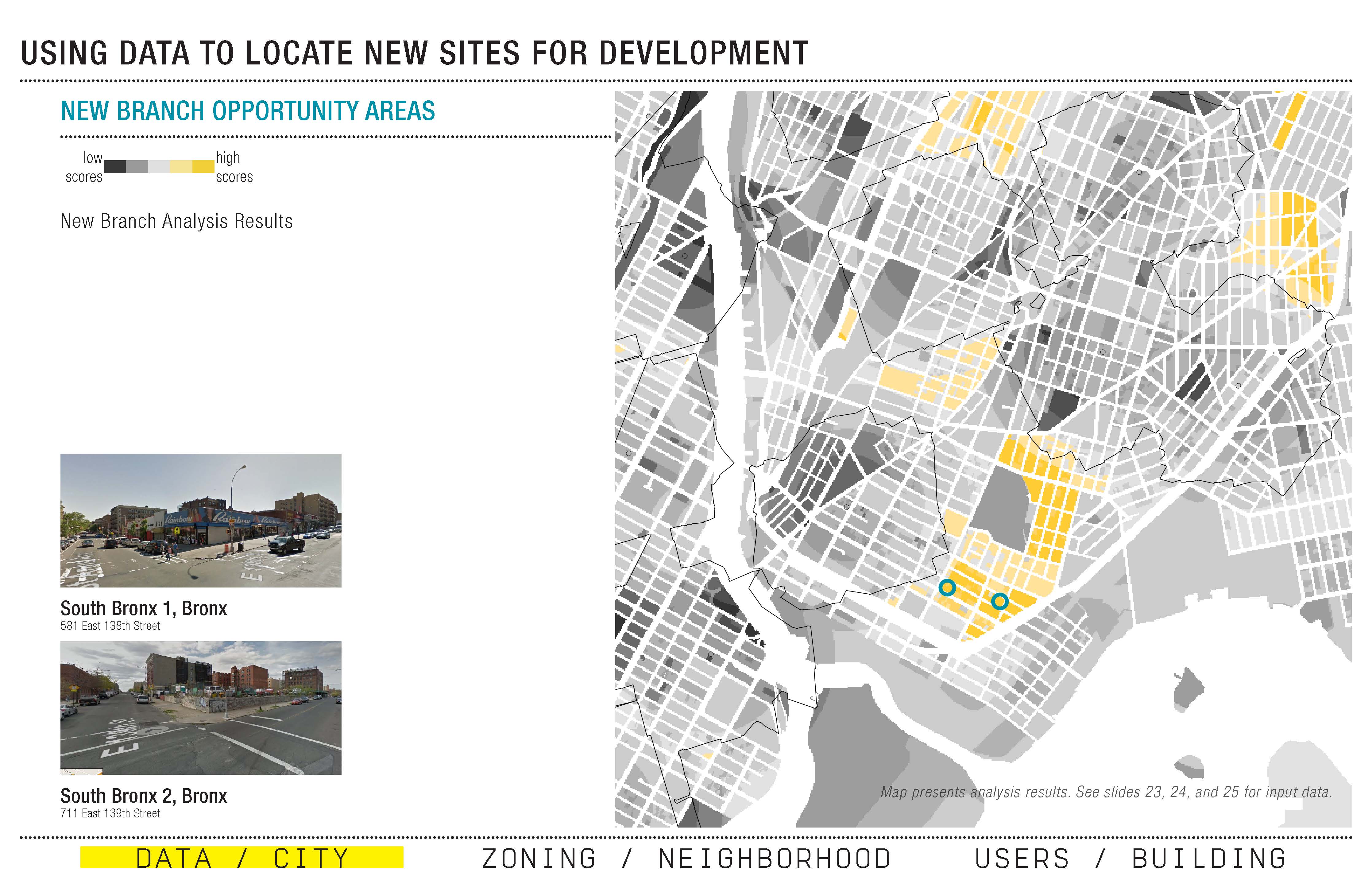

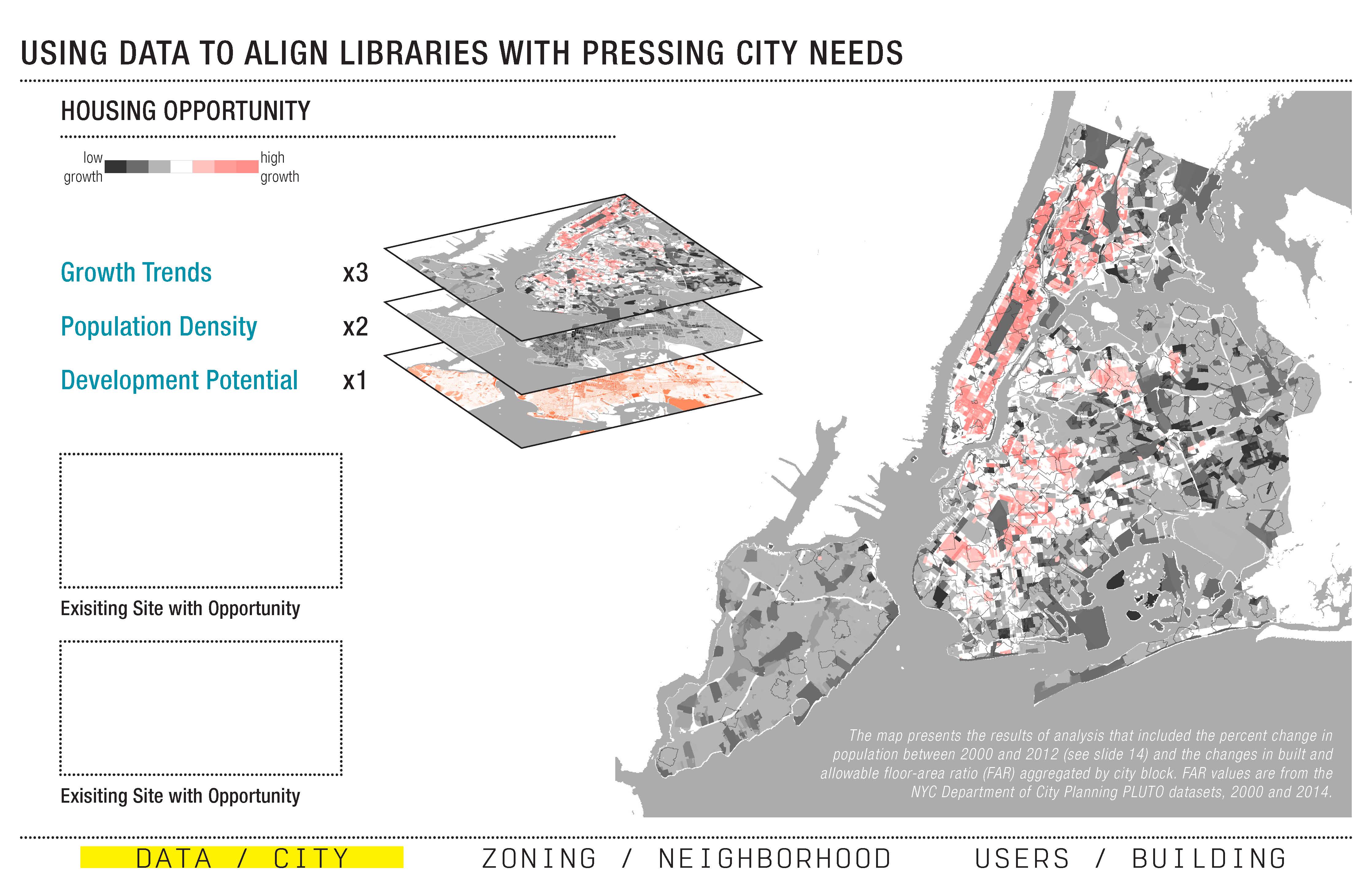

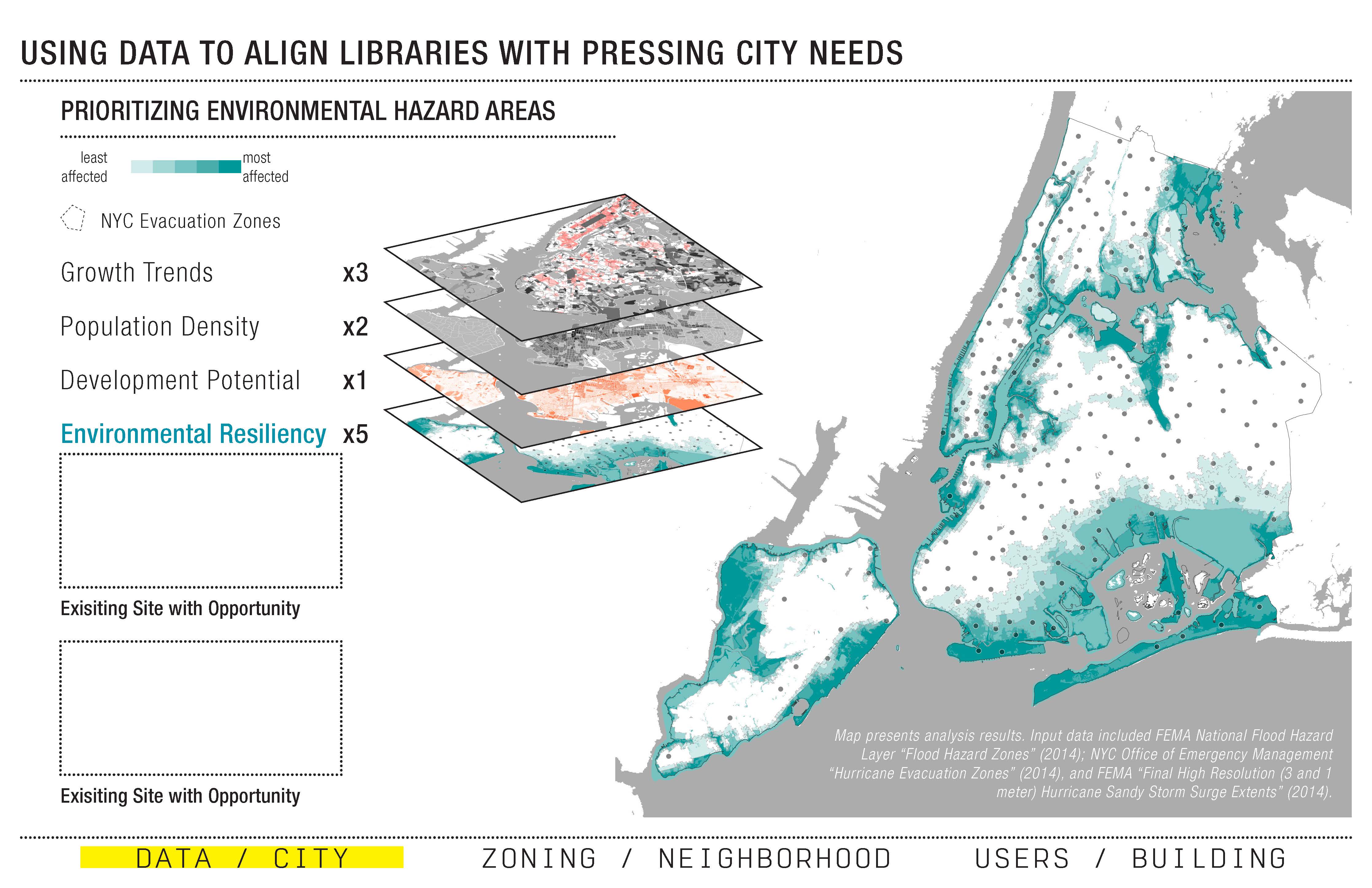

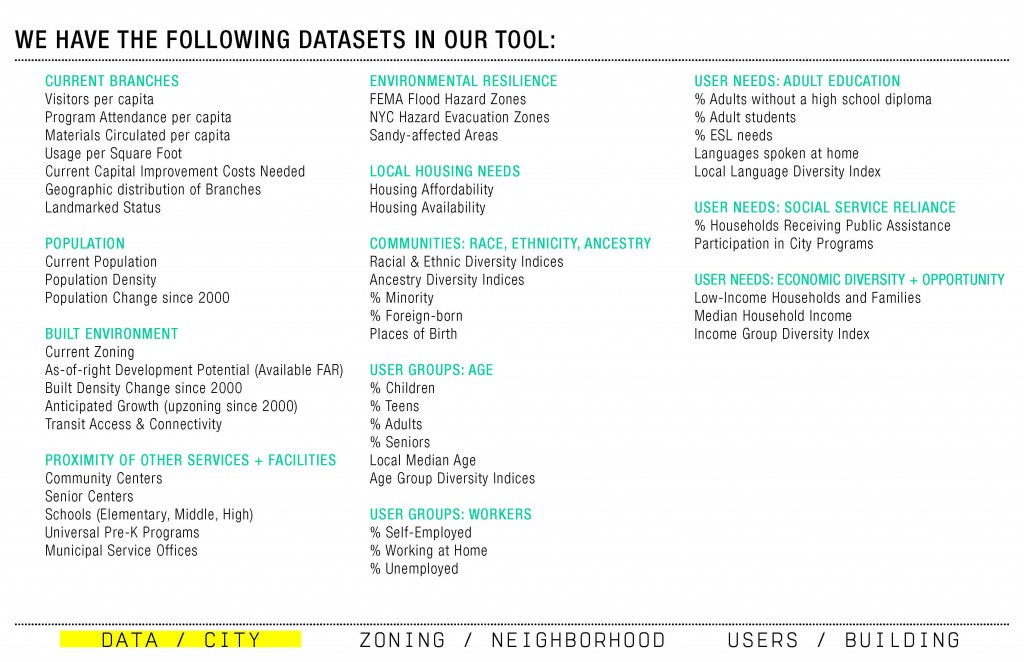

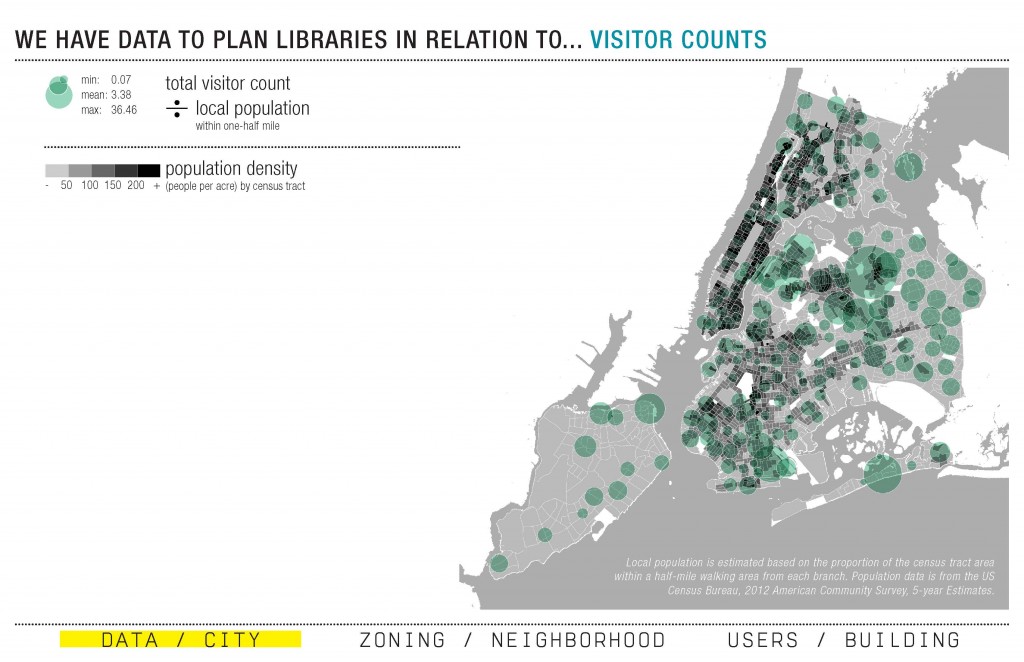

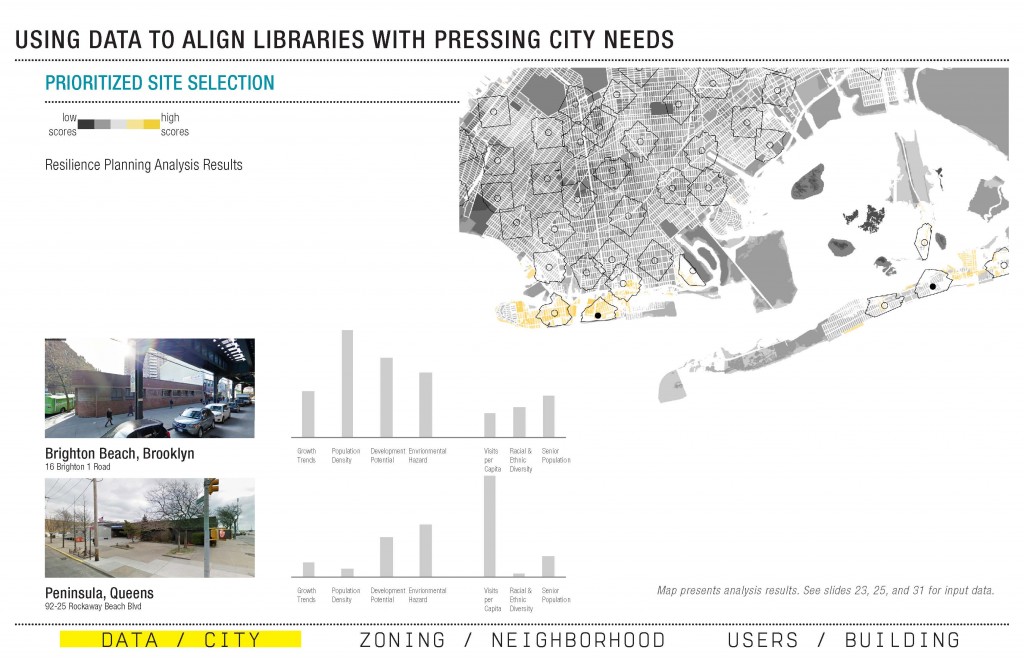

The team first took a citywide approach, creating a robust tool that leverages the City’s open data and other sources to strategically confront complex planning decisions. This tool incorporates a wide variety of datasets — including data on existing branch libraries, population demographics, development and growth potential, locations of other city services, flood and hazard zones, and more — to more effectively plan for the libraries in relation to other policy initiatives, such as disaster resiliency or affordable housing.

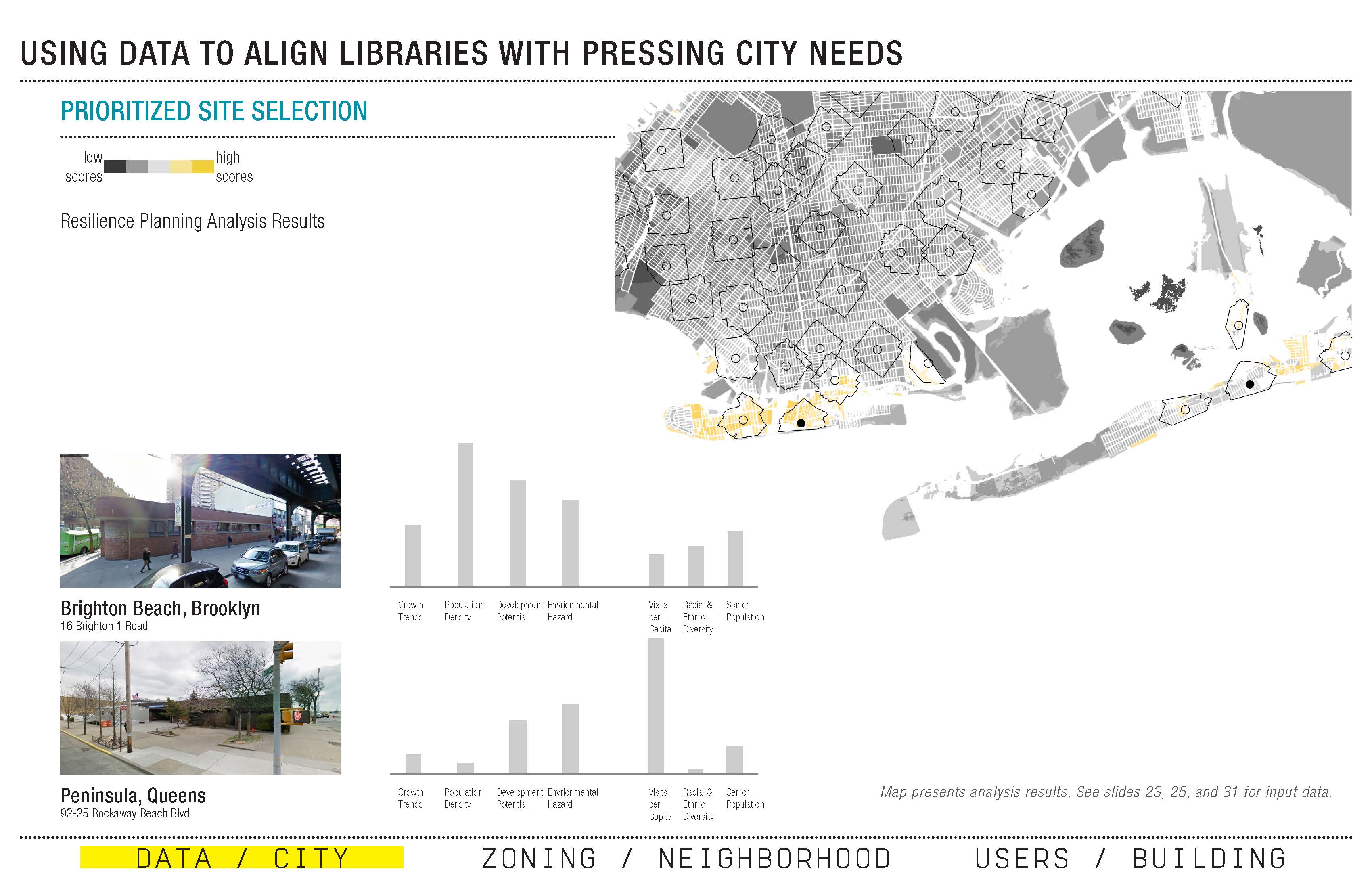

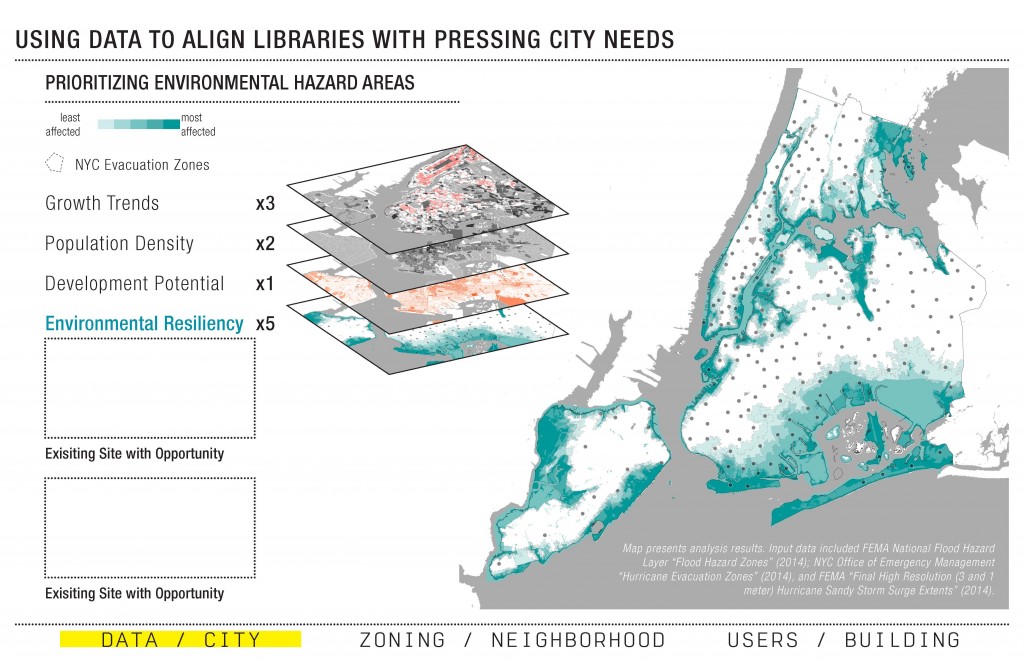

The team worked with the tool to not only compare multiple datasets at once, but also to weight layers of information to better understand existing conditions, perform site selection for new branches, or position libraries in relation to other city priorities. This comparative approach forces comprehensive planning, reflecting the reality that the branches do not exist in isolation to other resources, and allows for multiple planning scenarios. Wary of the “blind empiricism” of many data-driven approaches, the comparative and relational tool guards against singular, definitive answers. “We’ve built a tool that shows the result of combined priorities,” explains team member Leah Meisterlin. “It doesn’t lead to predetermined outcomes — it shows where you would focus based on your chosen goals.” The tool is meant for variety of constituents and groups to plan based on different priorities: “you don’t always ask questions from top down, you can also ask questions from bottom up.”

Using geospatial analysis, the tool clearly visualizes “hot spots,” or priority areas, based on the chosen datasets. In one example, growth trends, development potential, and locations of existing branches are weighted and analyzed relationally to identify neighborhoods in the city with a growing population and sites available for development, but without an existing library, as potentially good opportunities for a new branch. Another example demonstrates how the tool can be used to align libraries with pressing city needs, such as co-development of housing and environmental resiliency. By comparing growth trends, population density, and development potential for housing opportunities with City and FEMA data on environmental hazard areas — an analysis that shows that 74 branches, with approximately $264 million in capital needs, sit within the City’s evacuation zones, and another 75 branches fall within a half-mile walking distance – the tool can quickly identify sites worthy of further attention.

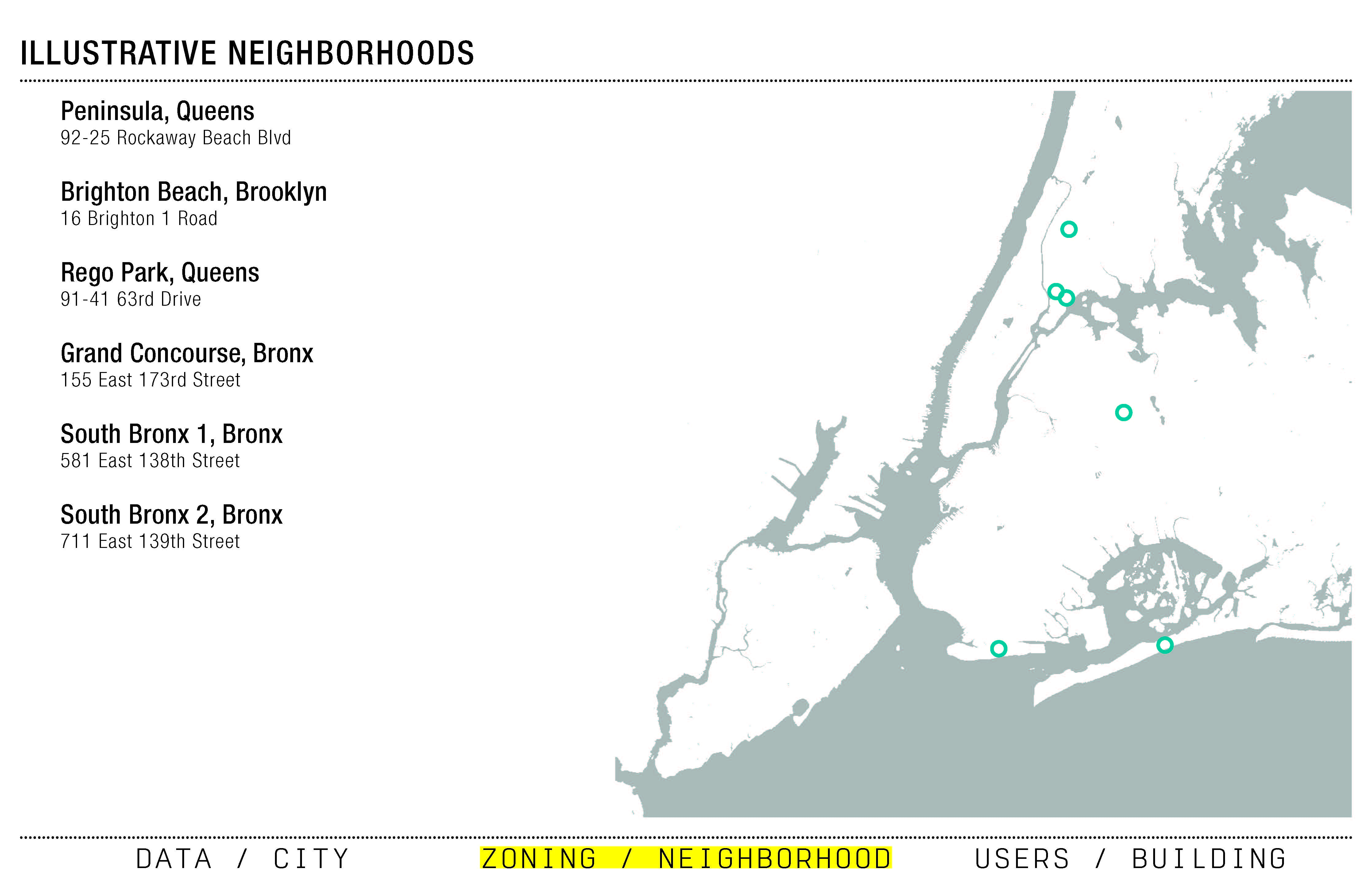

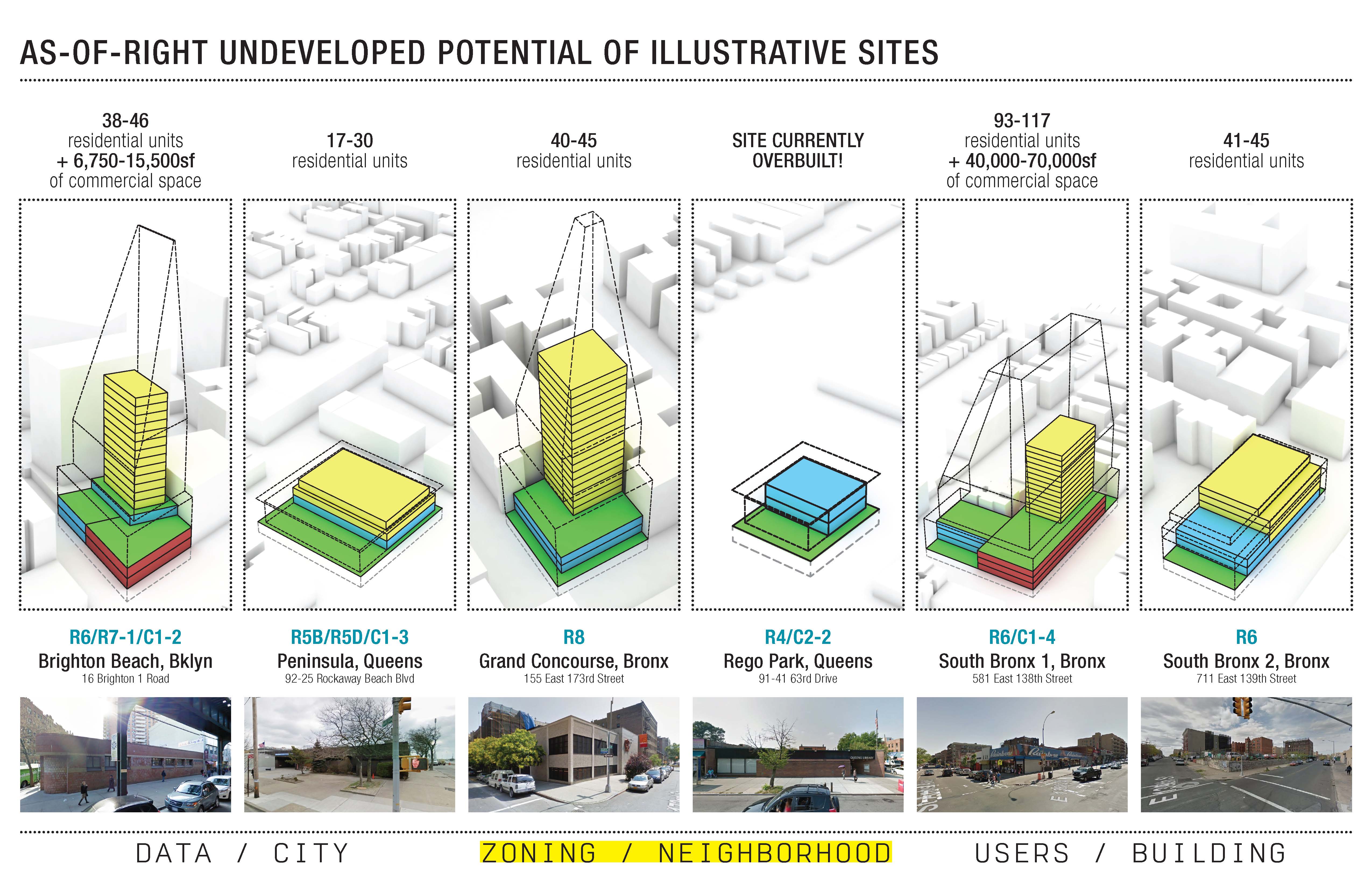

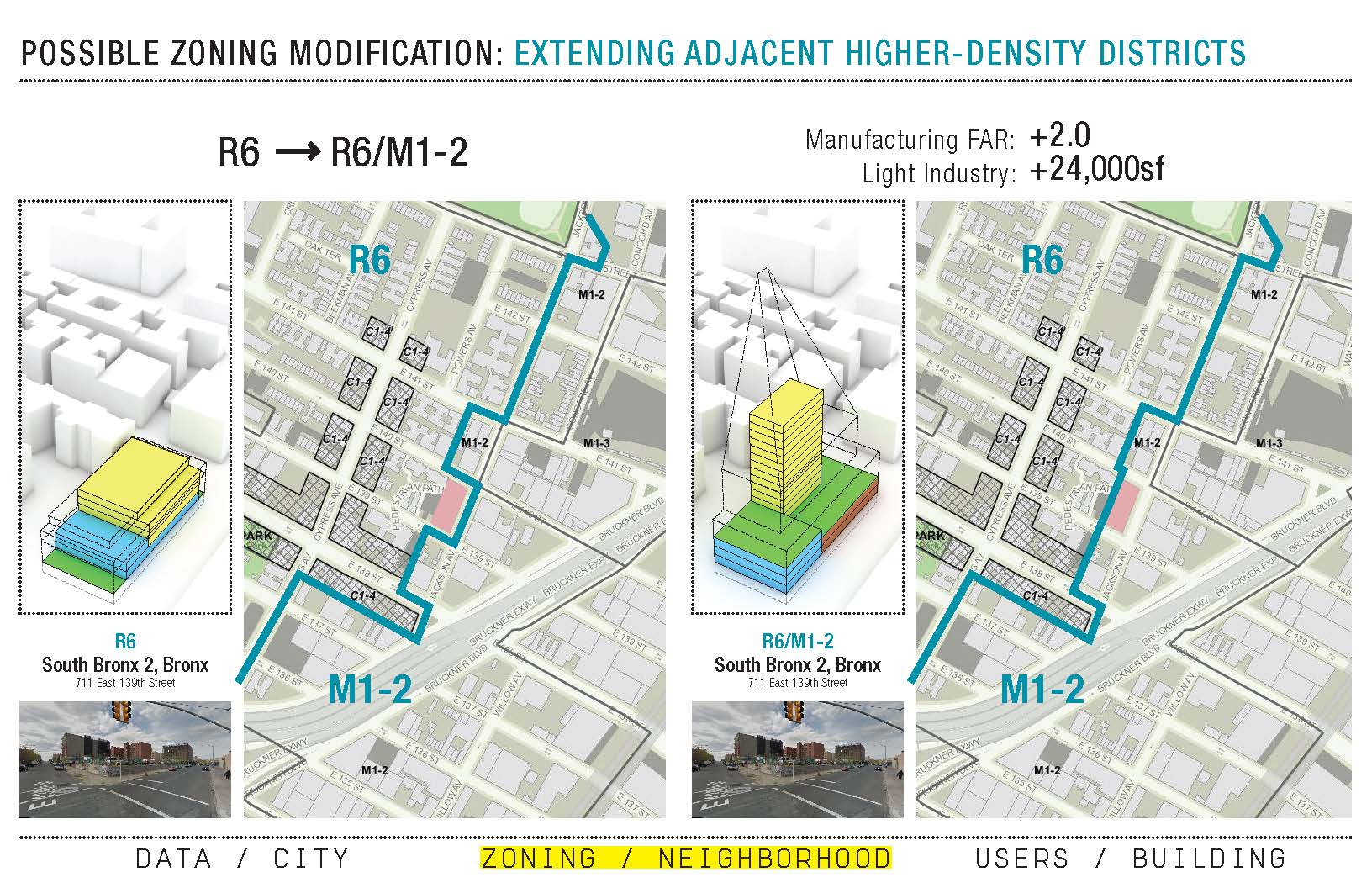

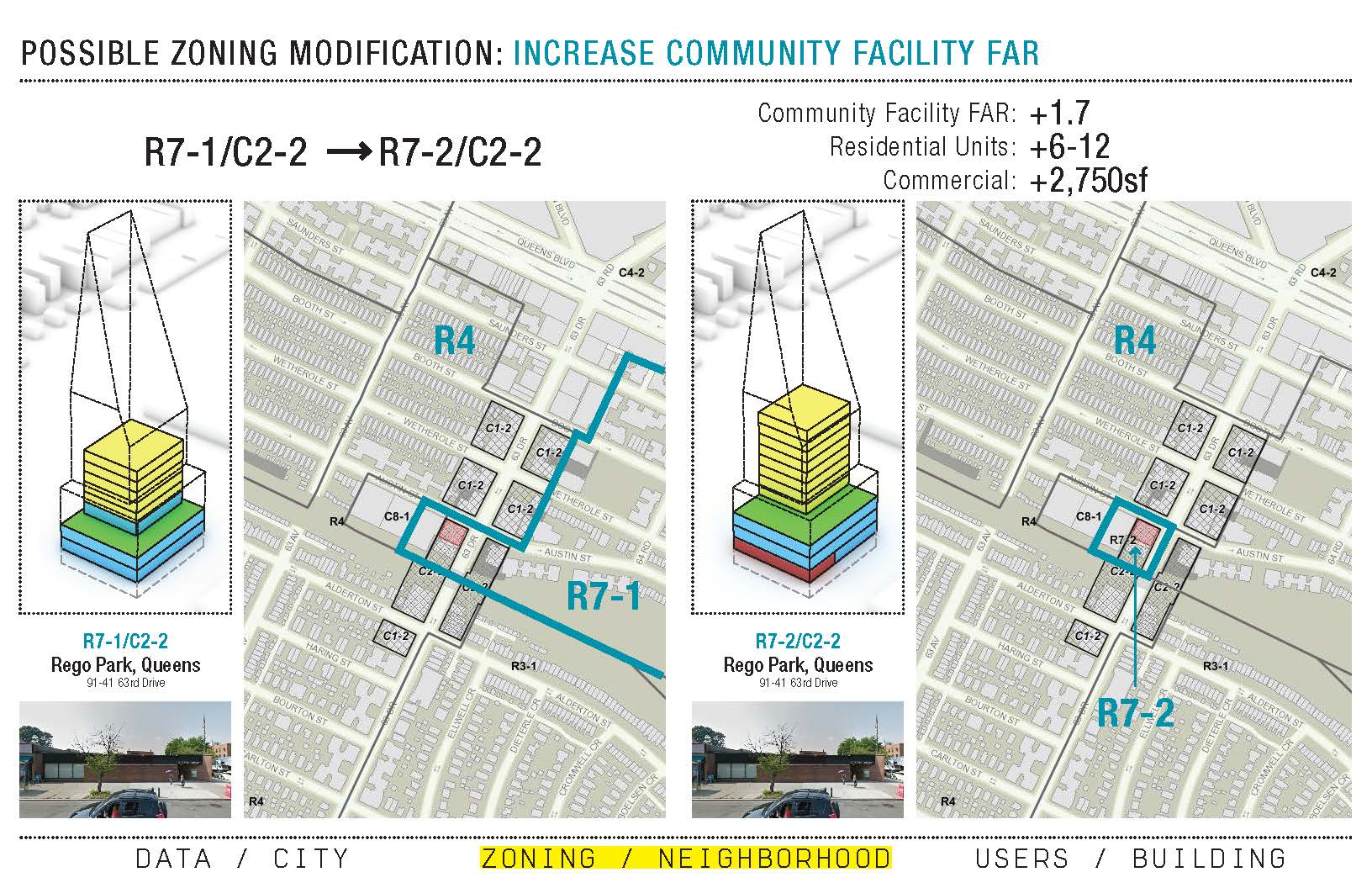

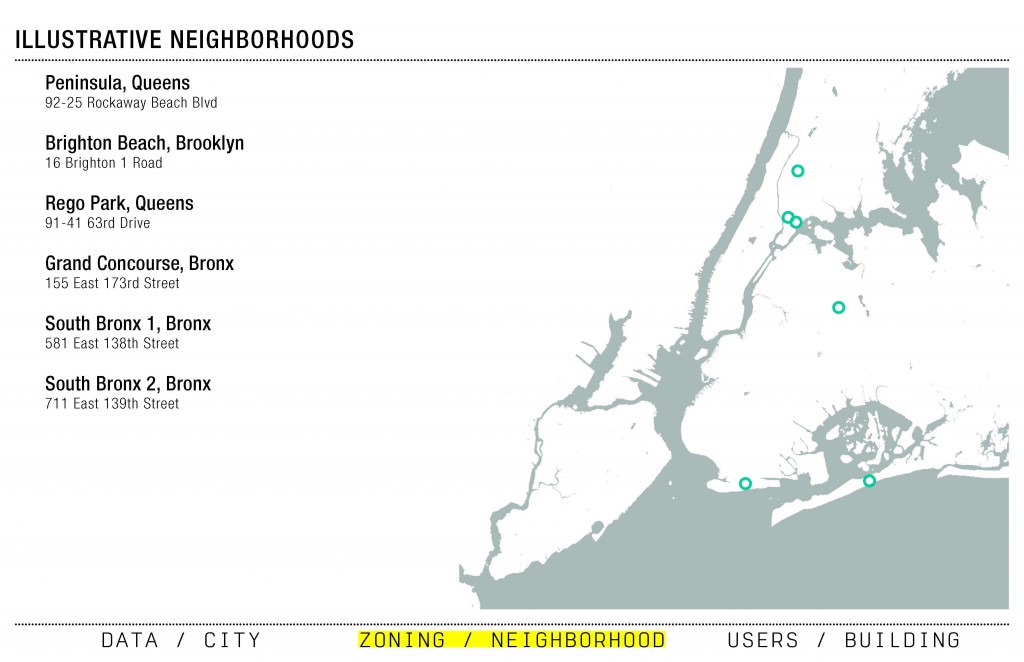

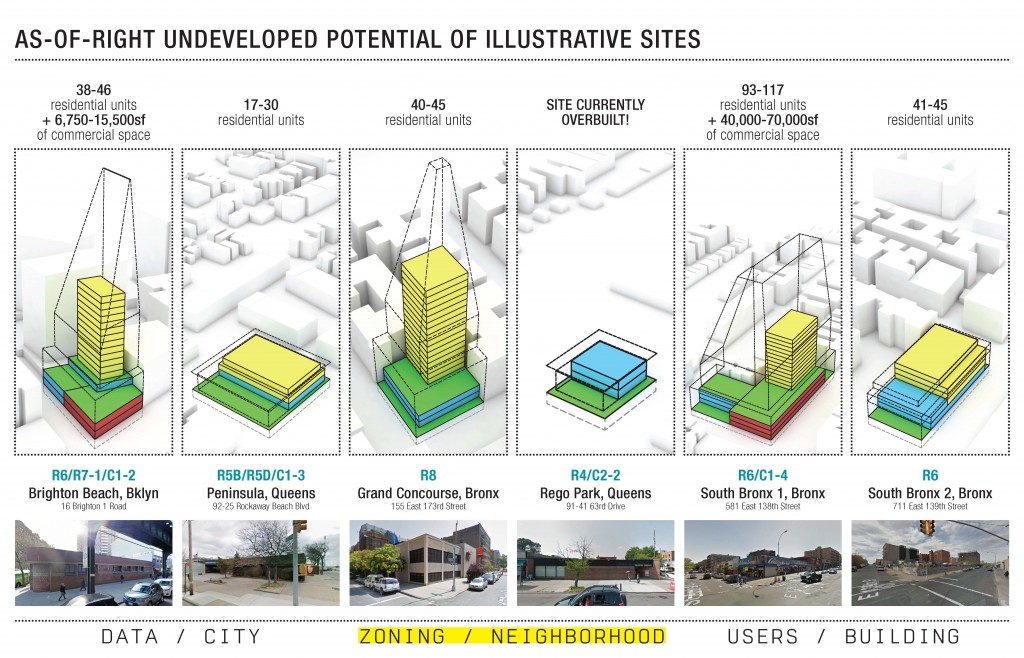

Zoning // Neighborhood

The team then shifted to the neighborhood scale, taking a series of illustrative potential development sites identified by the planning tool and conducting a more fine-grained analysis of their potential for community development in the context of land use, financing, and zoning options. Focusing on six case study locations, the team looked at as-of-right undeveloped potential and proposed strategies for integrating library space with new mixed-use and housing developments. The team then considered possible minor zoning modifications for these sites to increase allowable development, including permitting higher use on split-lot sites, extending a higher-density adjacent zoning district to the site, upzoning to increase the community facility floor-area ratio (FAR), or providing a zoning bonus for integrating storm resiliency and emergency response centers. The zoning tool demonstrates, according to Fairbanks, “how to leverage the site, and how to get communities what they need — including better libraries” while supporting other city goals. “How do you leverage what some groups need with what other groups need?” asks Meisterlin. “We might be zoomed in on a few blocks, but we understand that what happens on those few blocks has a citywide ripple effect.”

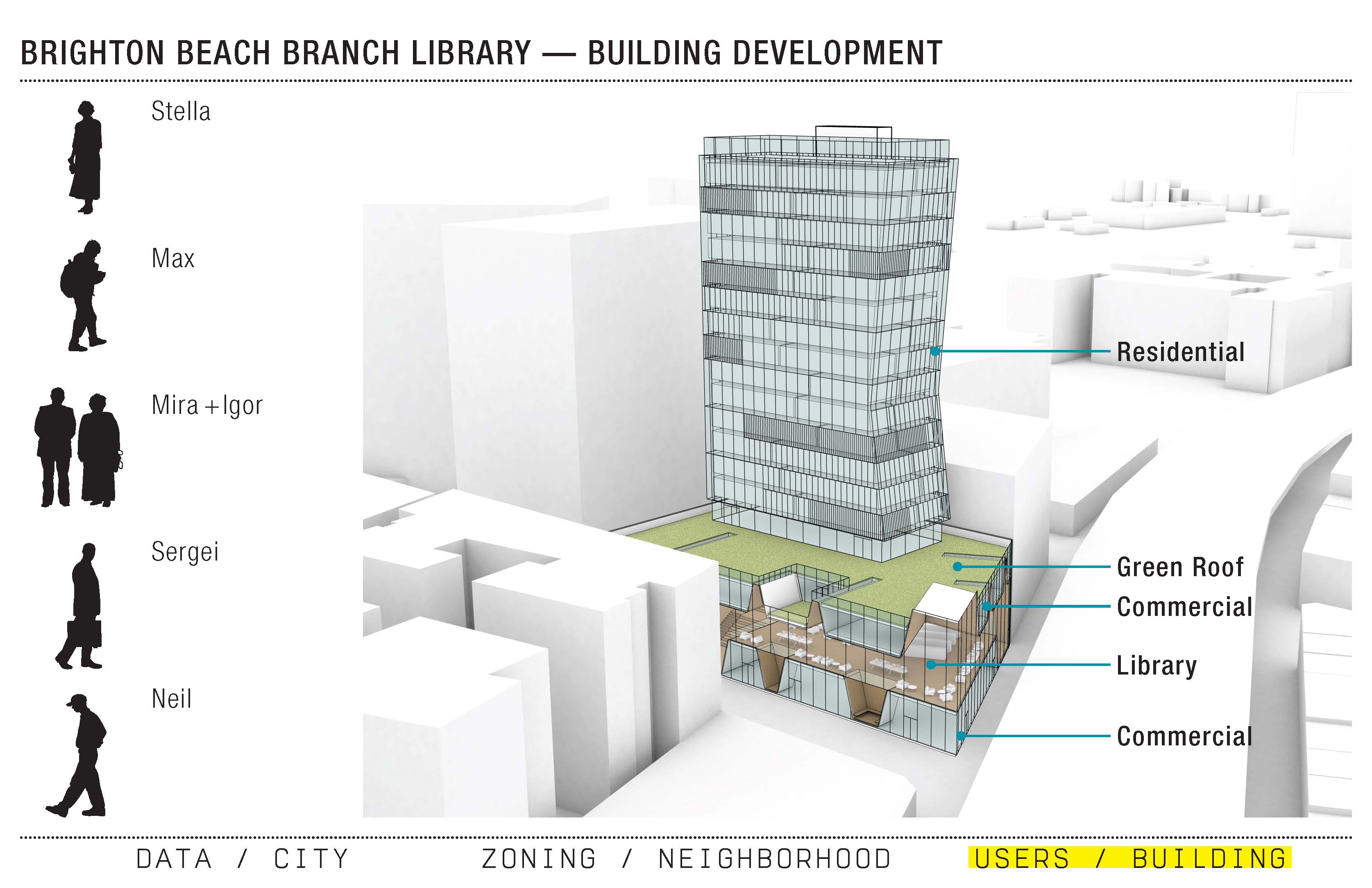

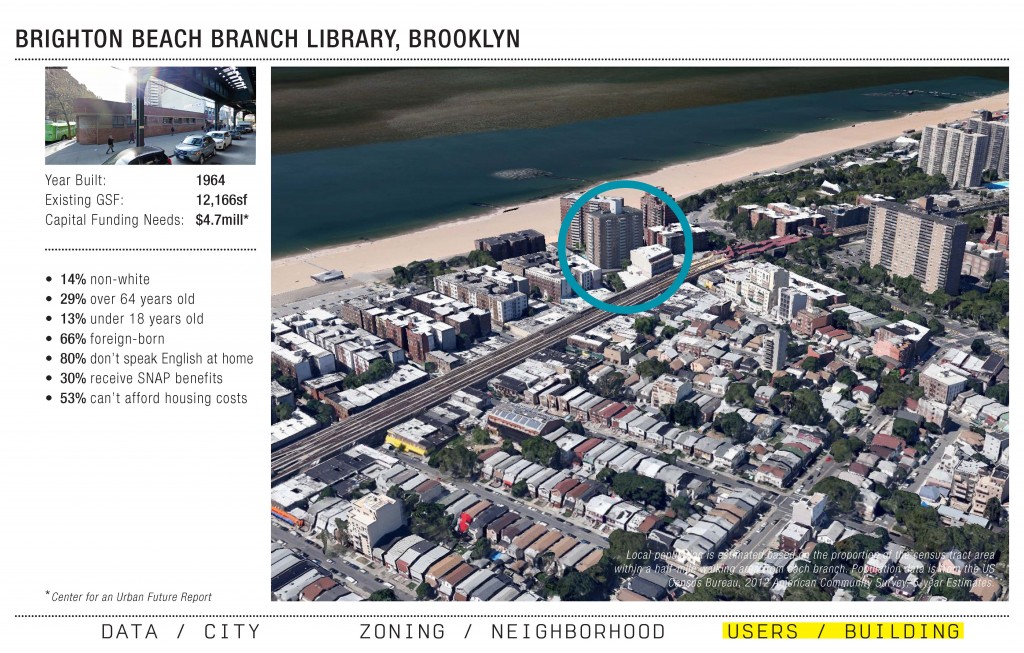

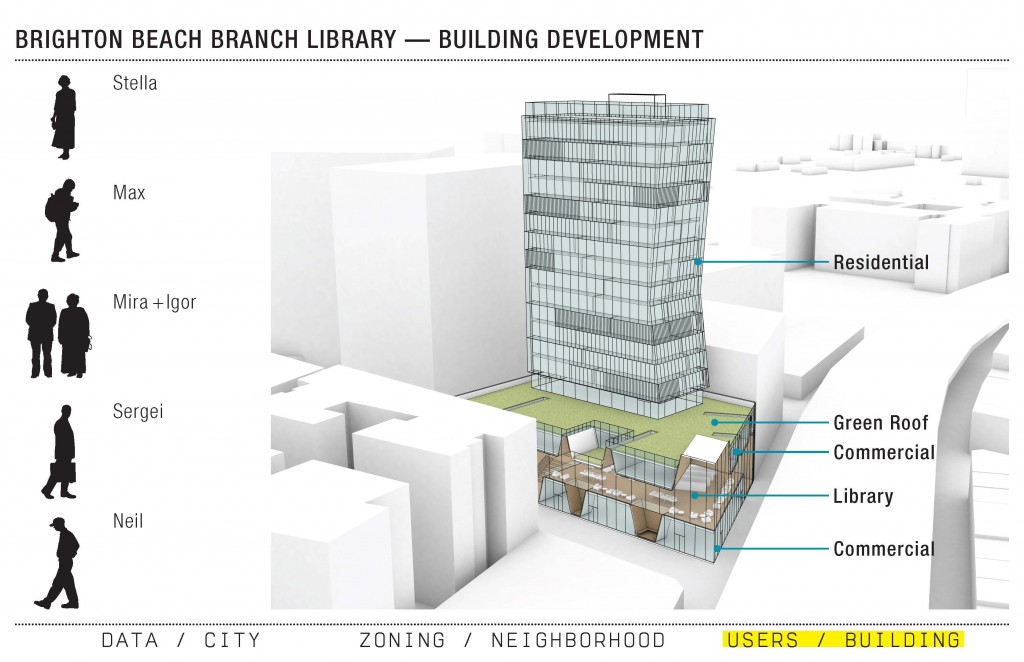

Users // Building

The team next zoomed in to the building scale, using the Brighton Beach Branch Library in southern Brooklyn — a 50-year-old, 12,000-square-foot building with nearly $5 million in capital needs — as a case study. The team proposed replacing the existing branch with a new mixed-use development that has a 20,000-square-foot library at its center. Telling the story of this new development through six fictional Brighton Beach residents who use the library for different needs, the team demonstrates sensitivity to context and local needs. “The data are people,” Meisterlin says. Data-driven design is not merely technical and cannot be divorced from real user needs.

While acknowledging that co-development with branch libraries can only be “a minor piece of the affordable housing puzzle,” the proposed 58 units of affordable and market-rate housing could have a significant impact in the neighborhood, while also providing new retail space. The library as a critical piece of the city’s resiliency infrastructure is particularly noteworthy considering their use as relief centers following Hurricane Sandy, as well as the team’s finding that 74 existing branches (including Brighton Beach) are located within evacuation zones.

The team assessed possibilities for co-development with care and was committed to maintaining the civic identity of the library within a mixed-use project. Combining the library with private development is not right for every library and every community, and when this strategy is employed the library needs to be “open, public, and yours as a community member,” says Fairbanks. When co-development works, it funds a new library (mitigating outstanding capital needs in the process) while simultaneously providing real estate value and strengthening the library’s position as a hub of the community.

Ultimately, what the team designed is a civic process for informed decision-making, combining data-driven outcomes with a human-centered approach to design. “We need our cities, and city spaces, to be about people,” stressed Meisterlin. The planning tool uses public data not “as absolute fact,” she explains, but as an instrument to guide “how to act and where to act, how to allocate resources.” The potential for these tools to provide an intelligent framework for more informed planning is enormous. The team hopes to continue development and create a user interface for a multi-scalar tool that has applications and uses far beyond branch libraries in New York City.

⋅⋅⋅

DOWNLOAD PDF

Download a PDF of the team’s presentation to see more on this proposal.

VIDEO PRESENTATION

Karen Fairbanks, Leah Meisterlin, and James Lima presented this proposal at a symposium co-hosted by the League and the Center for an Urban Future on December 4, 2014: