Along the Lumbee River, North Carolina

Along the Lumbee River: An Introduction

Initially, this report took the perspective of a typical architectural and urban design analysis by using environmental context and community data to tell a story about buildings and site interventions. However, through conversations with the contributors, the heart of the report grew to be about the larger environmental ecosystem of southern North Carolina, its people, and their historical and contemporary relationships to the land. In this way, buildings and site interventions became secondary to the narrative. The land—its history and the stewardship of it—are what we aim to honor and where the report begins.

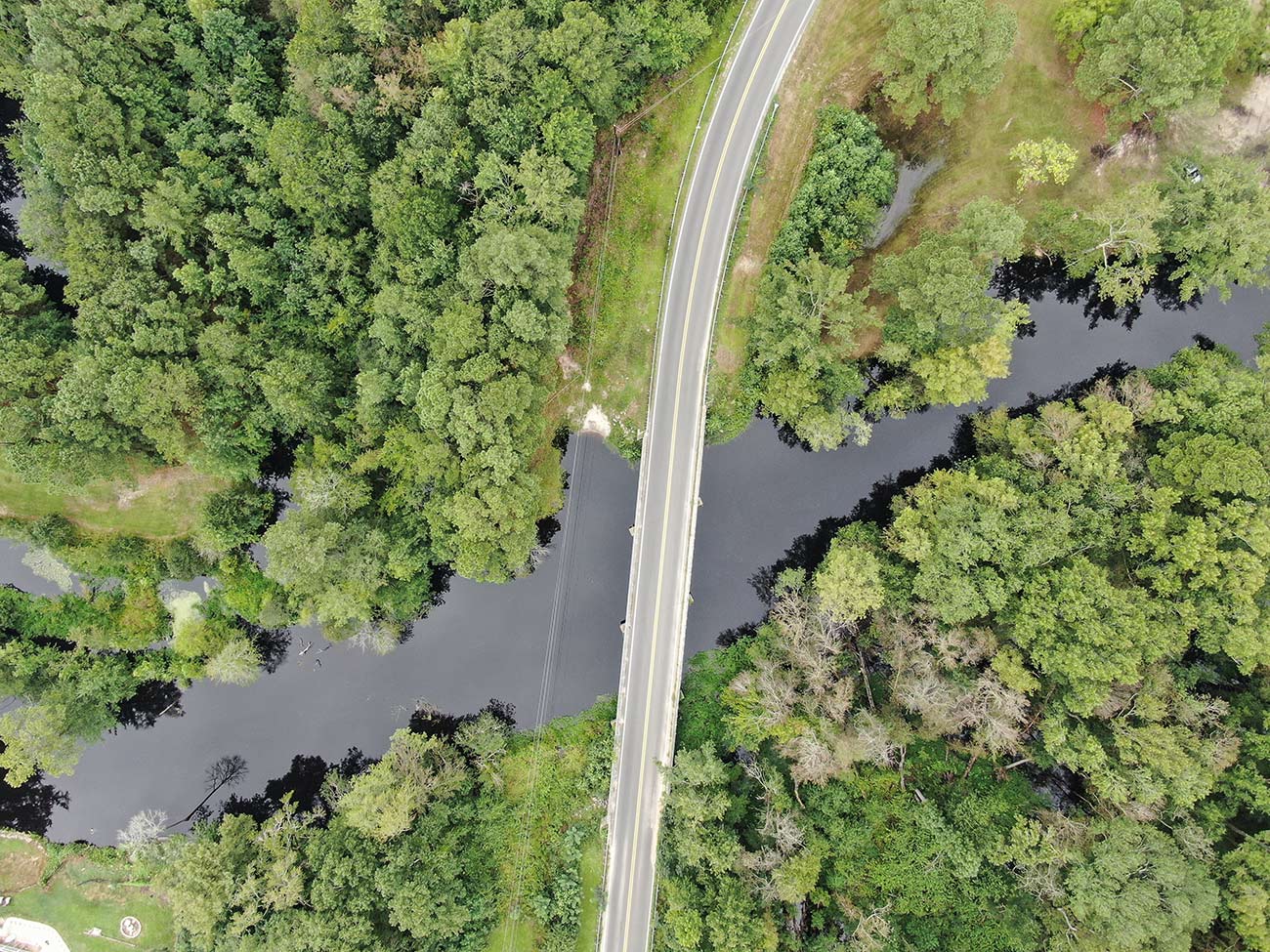

The Lumbee River—the reclaimed name of the Lumber River—is the namesake of the Lumbee Tribe, who have roots in the Siouan, Algonquian, and Iroquoian-speaking tribes and are indigenous to the southeast region of North Carolina, where this report is situated.1Lumbee Tribe, “History & Culture,” Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, 2019. This river—along with the Pee Dee and Waccamaw Rivers—has always served to connect people, places, and commerce throughout the region. It was on the Lumbee River where white explorers first made contact with Lumbee Nation ancestors.2The white settlers were surprised that the Lumbee ancestors had adopted some European farming techniques and some European dress styles. The Lumbee Nation’s oral history maintains that the community took in the white survivors of America’s lost colony of Roanoke in the sixteenth century, which may explain this. A natural infrastructure, it winds its way from Wagram through Pembroke and south into South Carolina, enriching the soil along the way. This natural irrigation path has historically made the region well-suited for agricultural use and supported farming as one of the region’s primary economies.

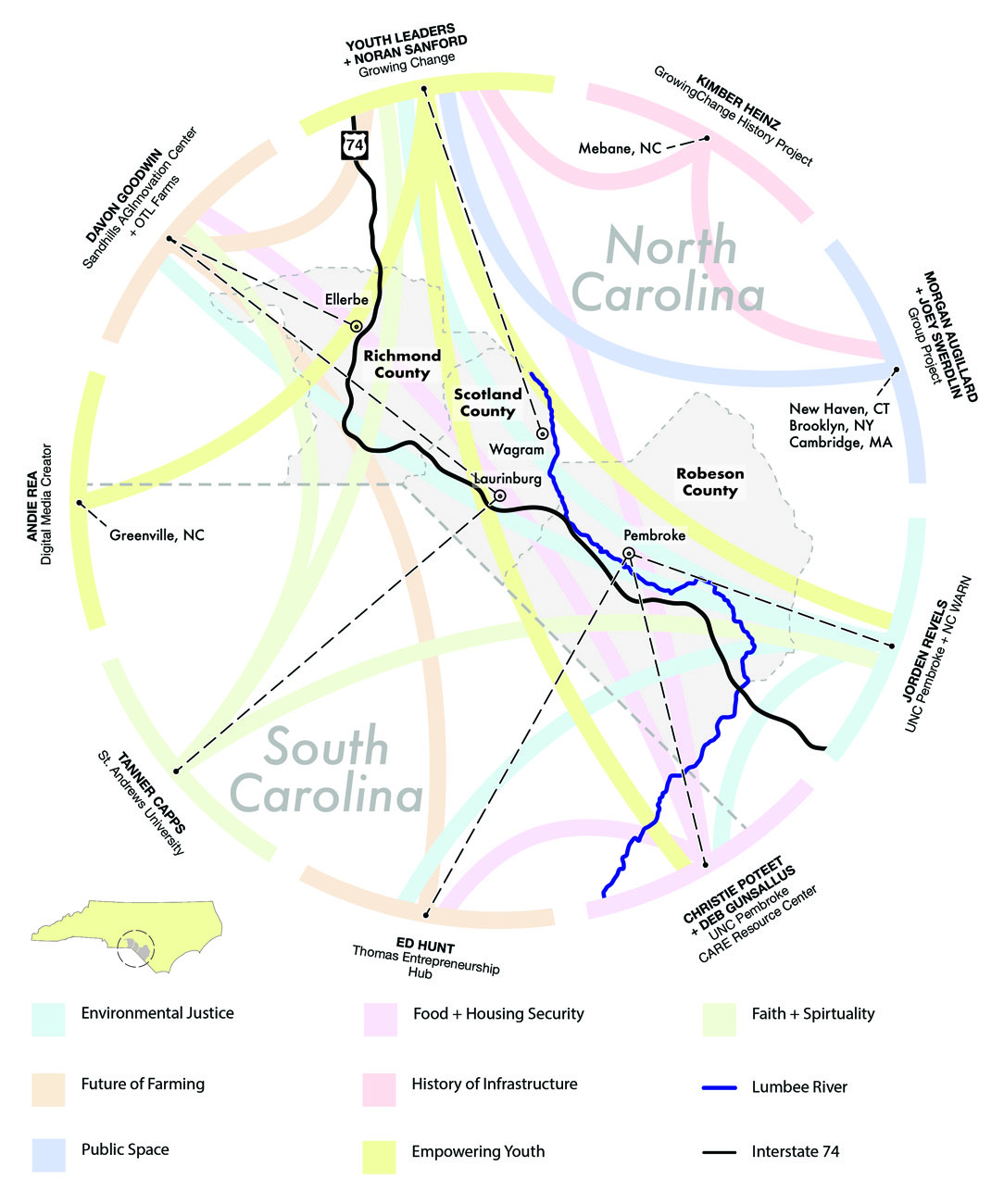

Left: The winding Lumbee River. Right: Interstate 74, which connects communities across the region. Credit: Andie Rea

At times following a parallel pathway to the Lumbee River, Interstate 74 is the infrastructural spine that connects an incredible network of community groups, youth leaders, farmers, faith communities, and local activists who make up the contributors to this report. In an hour’s drive down I-74, one may pass vast soybean and other industrial agricultural farmlands, longleaf pine forests, and several small rural towns filled with clusters of single-family houses, three-block-long Main Streets, and a mixture of fast-food chain restaurants and local haunts. This is the environment in which the contributors to this report live and work.

In addition to highlighting the landscape of this region, this report seeks to forefront its people and underscore the power of the intimate community networks that can be built in small Southern communities—relationships that are strengthened in front yards and over meals cooked by church community members.

This sense of hospitality brought the editorial team together in the first place. In 2017, upon invitation from MIT graduate student Insiyah Mohammad, Noran Sanford and several Youth Leaders from GrowingChange, a nonprofit based in the region, presented their work at the school’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning. During the lecture, they described their goal of flipping a decommissioned prison site into an agricultural community center. After the presentation, several architecture graduate students offered to assist GrowingChange with design projects during their summer breaks—and from there, a fruitful collaboration took root.

As this collaboration persisted from summer to summer, the number of graduate students grew. As a result, Group Project, a student-led design collective, was formed. (This report’s editors, Morgan Augillard and Joey Swerdlin, are current members, as are contributing editors Isadora Dannin and Kailin Jones.) Most of us in the collective are not native to the South, a rural community, or North Carolina.

This report has allowed Group Project to take a step back from design (especially since COVID-19 prevented our usual summer workshop from taking place) and delve deeper into the landscape of the community we’ve been working with for several years.

In addition to running GrowingChange, Noran Sanford is a co-editor to this report, and, as a Scotland County native, has spirited our connection to the area. Everyone who has contributed to this report and Group Project has shared unique perspectives and skills; however, it is Noran’s work and local community ties that have allowed it all to happen. His deep Scotland County roots and commitment have brought the editors and contributors together and anchor this report in place.

Along the Lumbee River is rooted in the communities of Robeson and Scotland County, North Carolina. Robeson and Scotland are two of the ten North Carolina counties that make up the Sandhills region of the state. The Sandhills region, which is characterized by its sandy and fertile soil, includes areas in South Carolina and Georgia that are located between the Coastal Plains and Piedmont regions. As a result, the area has been an agricultural hub (active in both producing and shipping); the city of Laurinburg in Scotland County was once called “The Capital of the Cantaloupe World.”3City of Laurinburg NC, “History, Lifestyle and more!”, Accessed February 23, 2021.

Presently, Robeson County (population 133,442) serves as the seat of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. Though the tribe’s lineage in the area dates back thousands of years, the Lumbee Tribe is still not federally recognized and does not hold sovereignty over the land.4Lumbee Tribe, “History and Culture”, Accessed February 23, 2021. The tribe’s continued fight for recognition serves as one example of the ways cultural identity plays out in this uniquely majority-minority rural community (39% American Indian, 24% African American, and 12% other races, with 25% white population).5Data USA, Robeson County, NC. Neighboring Scotland County has a similar racial breakdown (44% white, 39% African American, 11% American Indian, 6% other races), but with less than a third of the population (pop. 35,262).6Data USA, Scotland County, NC.

On paper, both counties present a racially mixed demographic, but many towns are still segregated along racial lines. During a Group Project visit to North Carolina, a GrowingChange Youth Leader described the way segregation manifests on the landscape. As we crossed railroad tracks in Gibson, the youth leader highlighted how the housing size and type shifted as we left the “white part of town” and entered the poorer Black neighborhood.

These historically segregated housing conditions are typical of the region’s smaller towns, where population growth has stagnated. By contract, larger cities such as Laurinburg are seeing growth and racial integration as new people move in.

The region’s economy boasts a rich agricultural history, but the health care/education sector, manufacturing, and retail industries top the lists of job producers in both counties today.

In recent years, local leadership has become more reflective of the racial demographics of the region, though conservative, Republican political views remain dominant and show up across racial lines.

Working with GrowingChange has given Group Project an opportunity to continue building relationships with the organization and its community partners. While this report includes contributions from Noran Sanford, GrowingChange Youth Leaders, and Group Project, it primarily seeks to lift up the work of the partnering community organizations and the incredible people who lead them. What is most compelling about these contributors is the breadth of their community-activated work, the interconnected networks of support in rural communities, and the multitude of people knowingly and unknowingly enacting similar theories of change.

In their work, the contributors to this report grapple with local challenges daily—legacy federal and state disinvestment that has resulted in high poverty rates, food insecurity, high crime rates, and lack of youth support. Additionally, the infrastructure and economy of these counties has consistently been hit by environmental and social disasters, including devastating damage from recent hurricanes, poor health outcomes that plague predominantly low-income and BIPOC communities, and now the COVID-19 pandemic: Robeson County has one of the highest rates of infection in the state.7Kummerer, Samantha, “‘So much bigger than COVID’: Lumbee Tribe combats virus in county with 3rd highest percent positive tests in NC,” ABC 11 Eyewitness News, August 28, 2020. The rural location of these communities further limits the availability of resources.

Many of the voices shared in this report, particularly those of Black and Indigenous perspectives from rural communities, address historic and present social experiences that are often ignored or overlooked by popular media. Throughout the pieces, the contributors acknowledge the active oppressive nature of systemic racism and class discrimination in each of their fields of work, motivating their own push for justice.

Below is a brief introduction to each of the contributions:

Stories from the Inside: Four Eras of North Carolina Prison History

- Kimber Heinz details the interconnected history of incarceration and infrastructural development in Scotland County.

Spirituality and Public Space

- GrowingChange Youth Leaders reflect on The Farm, the GrowingChange campus.

- Tanner Capps examines how a predominantly white congregation grapples with social politics.

Future of Farming

- Davon Goodwin shares his story of starting a farm from scratch.

- Ed Hunt discusses entrepreneurship in farming.

Getting Reacquainted with the Land

- Jorden Revels connects Indigenous heritage to contemporary environmental justice.

- Noran Sanford creates new methods for empowering youth.

A New Standard of CARE

- Christie Poteet and Deb Gunsallus detail how a university can provide housing and food security to its students.

Flipping the Prison

- Group Project chats about its design practice and shares projects for community-led prison adaptive reuse.

Biographies

is a designer and urban planner working in educational real estate development in New York City.

is an architectural designer who currently works as community director at Morpholio. He is based in New Haven.

Augillard and Swerdlin are members of Group Project, a collective of former and current MIT students that has worked with nonprofit North Carolina-based youth organization GrowingChange for four years.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.