Everything can be architecture

An interview with Mexico City's LANZA Atelier, winner of the 2017 League Prize

The League Prize, an annual competition that asks young designers to respond to a given theme, has marked an important milestone in many architects’ careers. Winners showcase their work through a lecture series and exhibition.

LANZA Atelier was one of the 2017 Prize recipients. Cofounders Isabel Abascal and Alessandro Arienzo discussed their work with the Architectural League’s Catarina Flaksman and Matt Ragazzo.

Flaksman: This year’s theme for the League Prize competition is “Support.” What does this mean to you and your work?

Abascal: Support has two main meanings for us. The first is that architecture lives with gravity, so you need support elements to make it possible. And there is a more abstract meaning that has to do with things that make the discipline go further.

The first meaning, the one that’s about something hard and heavy supporting something lighter, can be subverted in contemporary architecture. Our experience is that sometimes the things that are very light in our work, very ephemeral, have been the ones supporting projects that are longer-lasting, bigger, or even more solid.

Arienzo: These ephemeral projects are often exhibitions. It’s another way architecture can support other disciplines or spaces.

Flaksman: Can you talk about your installation for the League Prize exhibition?

Arienzo: We wanted to show projects and at the same time make a piece of architecture. We designed the installation to blend into the space, choosing a corner of the gallery to create a curved wall that tries to disappear.

Abascal: We were conscious that this was going to be a collective show, so we thought it would be fun to try to disappear. The idea is that when the public enters, they don’t perceive this wall. You need to make this special effort of observation to realize that there are peepholes in it. Curiosity leads you to want to look, and you discover these other worlds inside the wall.

Today we’re used to producing and consuming images very fast; with a computer you can produce 100 images in one minute. But to create the images we offered to the public through the peepholes, we dedicated many hours. We’re trying to decelerate the speed of image consumption.

We built dioramas of five specific projects. They don’t look realistic in the way that a rendering looks realistic, but provide a taste of the texture and light of these places.

Arienzo: In the studio, we don’t use much high-tech equipment. We make everything by hand. We produce things by talking to the carpenter, drawing things, and that’s it.

Abascal: It’s fun that the models are maybe in 1:50 or 1:20 scale and the wall is 1:1. We’re working with this difference between building something in 1:50 and something real.

Arienzo: That became interesting for our exhibition design project for the Jumex Museum. Passersby No. 2 Esther McCoy, the round structure in the exhibited model, uses the same system used in the 1:1 scale. We had to build the model the same way, making little rings to put the wooden pieces together.

LANZA installation "Passersby No. 2 Esther McCoy." Credit: Laura Cohen. Courtesy of Fundacion Jumex Arte Contemporaneo

Flaksman: You refer to exhibition design as “exhibition architecture.” Today, architecture and design are often used interchangeably. How do you see the relationship between these terms and your practice?

Abascal: It has to do with how we use these words in Spanish. We don’t have something that translates to exhibition design. People tend to use “museography,” replacing design or architecture.

Traditionally, people tend to think that exhibition design has to disappear, that it doesn’t need to have a presence. It becomes just interior design, in terms of working with the surface and locating things in space. But we think that every exhibition is an opportunity to test a spatial concept.

Arienzo: Design deals with objects, with things that can be more easily manipulated, while architecture is about space. I think that’s the main difference.

Abascal: It’s ironic that our largest work to date was an exhibition at the Mexican National Palace, which was around 2,000 square meters. It was a show inside this very old building from the 18th century.

LANZA’s design for the Art for the Nation show at Mexico City’s National Palace. Credit: Onnis Luque

Flaksman: You refer to exhibitions as “moments of possibility and study” due to their ephemeral character. Do you think museums and galleries provide a new context for the production of architecture?

Arienzo: Yes. When we’re dealing with more permanent building projects, we cannot keep testing and adding new ideas. But we experiment with ideas on other, shorter-term projects. Exhibitions give us more possibilities to put them into practice, to be sure about them, and even to work with a client.

Abascal: We have a responsibility to take advantage of the open conditions of exhibitions to experiment and push the boundaries of our practice.

League Prize competition entry pages featuring LANZA’s design for the Art for the Nation show at Mexico City’s National Palace.

Flaksman: Apart from exhibitions, your practice also includes publications. What’s their relationship to your projects?

Arienzo: We’re very interested in how architecture is represented, and I’m interested in how architecture works. How do you construct the drawings? It has to do with confronting architecture and putting its definition in a very ephemeral and ethereal place. We never know where the actual architecture is; it’s not in the constructed building, because that’s already a building. We play with that nonsense. And we make a statement that architecture is everything, in its own way.

Abascal: Everything can be architecture. We do many different things, and I personally regard everything as architecture.

Also, as for representing architecture, when you’re designing you mainly use images. If you look at the history of architecture, the new means that people have had to design, represent, and draw have had an impact on form and in the way that architects were producing at a certain phase in time. We tend to reflect on that and come back with other ways of representing or questioning ourselves when we are drawing architecture.

Flaksman: How do your ephemeral works relate to your long-term projects?

Abascal: We wrote a short essay for the League Prize entry entitled “Only What Is Bound to Disappear Remains.”

Many icons from the history of architecture were meant to disappear very fast, like world’s fair pavilions—the Eiffel Tower, of course, but also many others. Ideas and concepts remain. You never know the timeline in which something will materialize and remain important.

Flaksman: What or who are your main influences?

Abascal: Obviously there are many architects that we admire, but there are also many artists, filmmakers, authors… 50% of what influences us is just walking down the street and exploring.

We don’t have a list of architects, but there are some favorites. We are very fond of the idea of playing with perspective and trying to trick the eye. This has a lot to do with the Renaissance, with Brunelleschi’s and Bramante’s work.

Fifty percent of what influences us is just walking down the street and exploring.

Arienzo: And we like Junya Ishigami’s concepts, because they are more like art ideas—they are really conceptual, and he actually puts them into architecture. It’s like, whoa! How could he switch it and nobody noticed until now that it’s built? That’s very powerful.

Abascal: He manages to blur the boundaries between architecture and the context of the living environment. He is not trying to do architecture: he’s trying to contribute to the world, he’s trying to build nature. And it’s so beautiful because there’s no opposition between the two anymore.

Arienzo: And there’s another character, Juan O’Gorman, a 20th century Mexican architect. He mixed a lot of art with architecture and local craftsmanship. He completed an enormous library in Mexico [UNAM Central Library], full of murals. It’s super powerful.

Abascal: Craftsmanship has a lot of importance in Mexico.

Flaksman: How do you see your practice developing in the next years?

Arienzo: When our studio was one year old, we asked ourselves where we were going. And now, with our 13 projects or so, we can actually understand it a bit better. We do these publications, these exhibitions, and now we’re doing houses. Probably in two years we will be making a small building, hopefully. The idea is to conquer all activities.

In the end, the architect just coordinates things and makes decisions—the right decisions. So my goal is to work less but produce more. And to continue to investigate other disciplines with the hat of the architect. I think the thing that keeps us in the studio is trying to get involved in some other worlds.

Abascal: Since we started LANZA, I can’t remember a single project that we’ve done that we didn’t enjoy and didn’t believe in. We’ve somehow managed, by being lucky and many other factors, to do things that we believe in and are excited about. For me this is the most important thing.

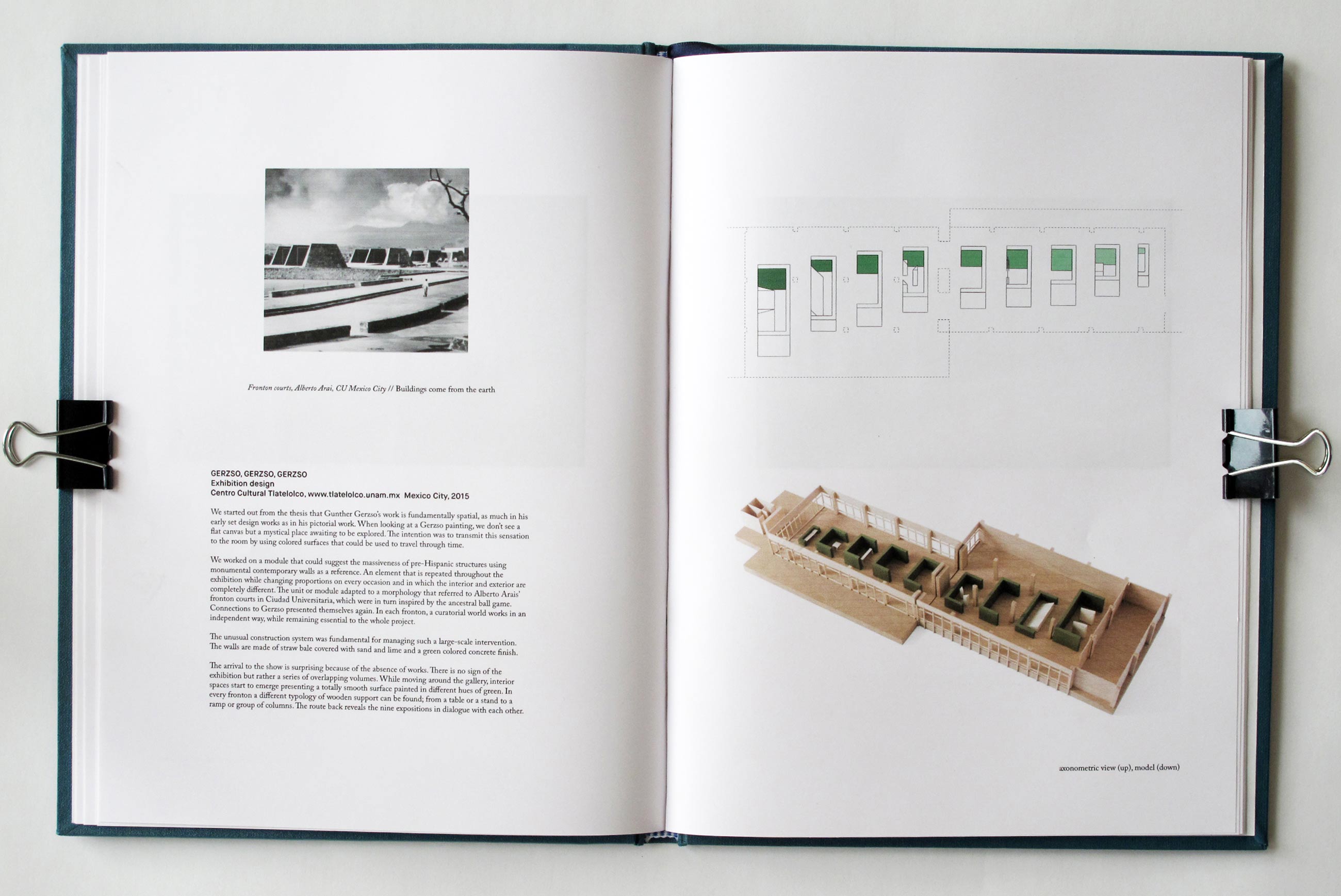

A page from LANZA’s League Prize competition entry featuring an exhibition created for Mexico City’s Centro Cultural Tlatelolco.

Arienzo: And something really important about architecture: it’s the most tangible opportunity to make something good for the world. But if you make it bad, it’s the worst thing that you can do to the world.

Abascal: Having fun is one of the main objectives. When you’re having fun with what you’re doing, you know that it has a good intention, and it’s probably going to give people a good feeling.

Matt Ragazzo: Is there anything that we left off that you want to share?

Arienzo: There is another activity that we do, and we think it’s also like architecture: tattoos.

It’s fun to see the production of drawings, the process of producing something permanent, paired with the production of architecture. It’s the same: People ask for something but they don’t know really what they want. You have to read it, you have to draw it, you actually produce it, and it’s permanent.

Abascal: There’s this feeling that you’re contributing something to the world and to people.