Inventing f-architecture

Dissatisfied with conventional models of architectural practice, the designers behind the feminist collaborative created their own.

July 23, 2019

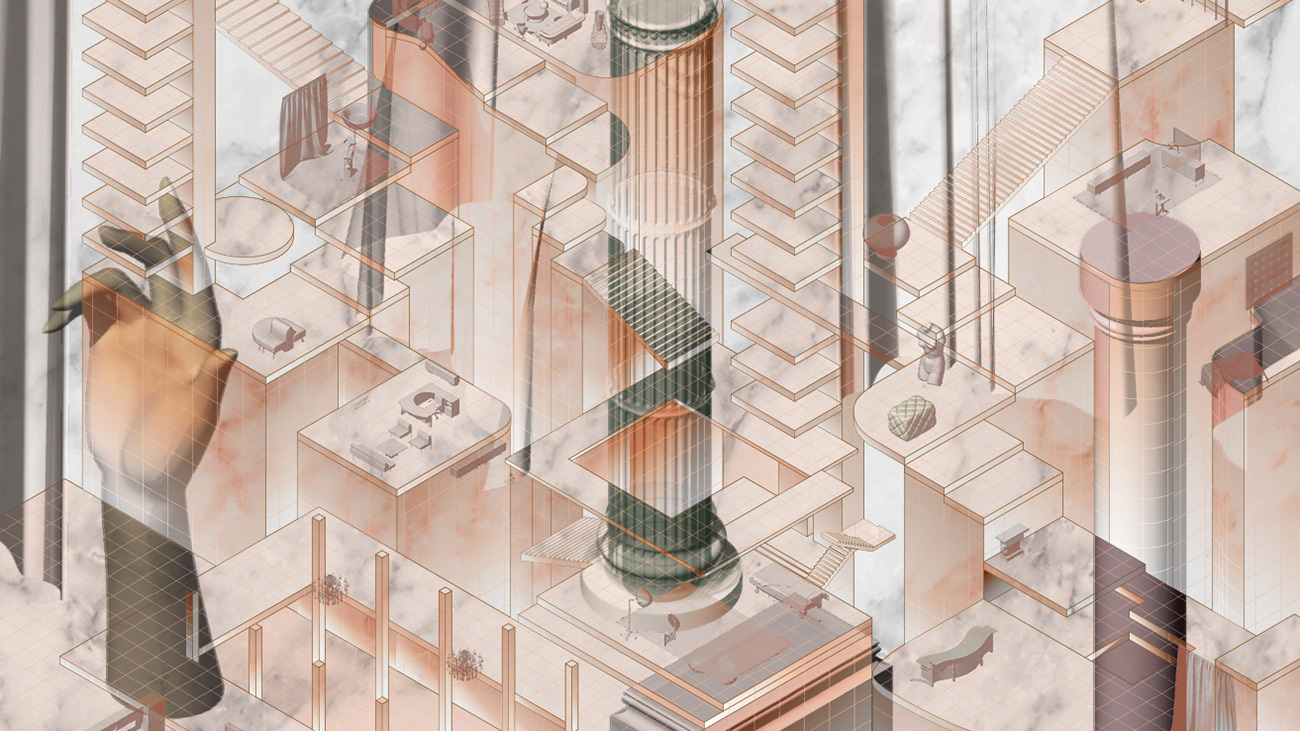

Cosmo-Clinical Interiors of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon, 2018. Courtesy of feminist architecture collaborative.

f-architecture is a 2019 League Prize winner.

The Architectural League’s Katie Rotman spoke with f-architecture co-founders Virginia Black, Gabrielle Printz, and Rosana Elkhatib about their work.

*

Katie Rotman: What first drew you all into the field of architecture, and then what pushed you into a critical practice?

Gabrielle Printz: I actually came from political science. For me, architecture was a way of acting in the world that was very different from politics or working in government, which were paths I had considered.

But I was almost immediately disappointed with what I saw as my choices for doing architecture in a conventional way. Even before we started working together, we all wound up circulating through weirder and weirder halls of academia to find this alternative way of being in architecture.

Rosana Elkhatib: Because of where I come from [Elkhatib grew up in Amman, Jordan], I had some concerns that I felt were very unfulfilled during my education. I needed space to understand not just Arab culture in general, but Arab women and their representation, which is often flattened outside the region, and made invisible inside the region. I felt that architectural tools provided a way to complicate this representation—to analyze it, and also to understand it spatially, because it has very real consequences for public and domestic spaces. This is something we’ve been looking at a lot.

Virginia Black: When I went to school, I thought architecture was simply designing buildings. And then I took a course with Martha Skinner, who combined various media to create what she called “Living Sections” of architectural and urban spaces. When I was introduced to her project NY A/V, where she used film to create a kind of CAT scan of the city, I realized architecture didn’t just deal in buildings, but in how we understand and make space broadly. I realized that this was the way I wanted to engage with architecture.

Rotman: How did you start working together?

Printz: We met at Columbia [in the Critical, Curatorial, and Conceptual Practices in Architecture graduate program], and we just decided to never part. Formalizing our friendship into a professional working relationship sounds like something out of late capitalist dystopia, but it made our collaboration this thing that was so embedded in our mutual admiration.

Black: At Columbia, we were all thinking about architecture in a similar way. All our projects dealt with putting our bodies into a particular landscape or context and thinking about them as entities we understand to be co-extensive with the project of architecture. We had been looking at similar foundational texts, a lot of which came out of Gabrielle’s research on the body when she was at Buffalo. [Before attending Columbia University, Printz completed a Master of Architecture at the Buffalo School of Architecture and Planning, focusing her thesis on the body.]

And then Rosana discovered the hymen suppository. And it was amazing to us, as people who were interested in thinking about the body as an architecture, as something that’s socially constructed. It became this thing that allowed our thinking to unfold.

Image from f-architecture’s 2018–19 Cosmo-Clinical Interiors of Beirut exhibition at the Vi Per Gallery, Prague. Credit: Peter Fabo, Courtesy of Vi Per Gallery

Printz: As an object, it convenes so many ideas and ways of working and researching. That project was sort of the impetus for the collaborative.

Rotman: How does your collaborative work, logistically?

Printz: We chose the word collaborative really decisively, because we saw ourselves as three actors with varied expertise that could come together in a way that was mutually cultivating.

Many of our projects have spun out of our individual work. Our work in Amman is largely owed to Rosana and her work with artists there. Our collaboration with AMUPAKIN (The Asociación de Mujeres Parteras Kichwas de Alto Napo), the Kichwa women’s midwifery in Ecuador, comes from Virginia’s work with them.

Black: On a field trip to AMUPAKIN, I became fascinated with the high level of skill of these women and started thinking about how my skills as an architect could assist them. That led to some of the projects f-architecture has done.

I feel like we have 1,000 ideas for projects, and then 10 of them become actual projects. Something I love about our practice is that it comes out of our friendship, out of these random conversations on the subway, at the bar, while watching Netflix and chatting on Insta . . . and those conversations sometimes develop into something much more studied and committed.

But how do we make the projects happen? It’s exhausting. We all have a billion day jobs and we work late hours. That’s the reality of it, unfortunately—we’re tired most of the time. Nobody wants to pay for “the weird hymen project,” so we have to engage in all of these enabling practices which make our financial lives precarious and our physical and emotional lives draining.

Part of the reason that it works is that there are three of us and we’re very dedicated to our common goals.

Elkhatib: We’re very obsessed with it, and so we’re doing it. We get sick, and we all have headaches all the time. And we also live in New York, which is its own kind of headache.

Rotman: Do you feel like New York is important to your practice?

Black: I think there is this expectation: Like, you have to live in New York to do this kind of work, or make it visible in a certain way. But I don’t know. I feel like we live on the internet or something. We live in a Facebook chat. It’s very bad politics to live in a Facebook chat, but we’ve already nested.

Printz: It’s hard to exist in this cultural economy where there’s an event all the time—but sometimes we’re the ones producing the events.

I think more than New York for its own sake, it’s just a place where we can share a space. We’ve triangulated in each corner of Bushwick. We can live near each other and near our other collaborators.

Rotman: You’ve talked about wanting to be mentors or models for people who don’t quite fit into the profession but who choose to be architects, whether it’s women or non-binary or queer people or people of color. Do you actively seek out that audience?

Black: It’s interesting to think about being mentors. That’s not usually how we frame it, although I would be honored to be considered a mentor. The way we’ve worked with AMUPAKIN and in Amman is that we are just collaborating with people who are operating spatially in a way that might not be acknowledged by the discipline of architecture. We’re trying to understand how we can support them in whatever ways they need.

But it can also be very helpful to think about how the discipline can benefit from understanding the ways that people like this practice—understanding other kinds of spatial agency that exist in the world. Particularly in terms of feminist pedagogy.

Printz: We also have to think about architecture as culture, and as culture that might also include or reflect a broader public. Our essay in the Harvard Design Magazine was really written for teen girls. We were reflecting on who we need to bring into the fold of architecture to expand the identity of the designer.

Rotman: Are there people who you consider to be mentors or models for your practice?

Printz: During my first year at grad school at Buffalo, I worked with Joyce Hwang and Martha Bohm on this conference called Beyond Patronage, which became a book that I co-edited. It was a way of assessing the kind of patronage structure that enables specific kinds of architectural work. But the conference was also a covert way of getting a bunch of women architects to speak about their practice in a way that didn’t make them so answerable to their gender. That was my first project in architecture, and I really have Hwang and Bohm to thank for shaping my ideas about being in practice.

Elkhatib: Some of my initial role models were artists who were spatial makers; they were architects in a way. People like Amal Kenawy, who’s an Egyptian artist, or Saba Innab, who’s a Jordanian artist and architect, were models for how I could use my architectural education in an alternative way.

Gabrielle and Virginia did introduce me to Liquid Inc. and other feminist practices, but that was after f-architecture started.

Printz: We all had incredible women who helped shape the way we approached architecture, but we had to invent f-architecture. We needed to establish a forum for doing the work that we didn’t see as possible in other positions.

Rotman: Some of your projects involve architectural pedagogy. How do you think pedagogy could evolve for the better?

Printz: We have lots of ideas about how to be a feminist in the academy, and about what feminist pedagogy is. I think it comes down to both critique and interdisciplinarity. Architecture has a tendency to silo itself off, but it also silos the many associated disciplines into narrow specializations wherein you have a specific set of tasks to do, but you’re less interested in taking stock of a wide range of problems. We think architecture needs to look outside of itself more, engaging other actors and being very self-critical of its position within systems of power.

Elkhatib: There’s also this foundational issue where there is no foundation. Even in the early stages of learning architecture, there’s an absence of feminist teaching.

Printz: We were just joking about inventing our own process of licensure with its own stamp.

Black: We’re going to make some short courses, and then you can be established as an f-architect.

Interview edited and condensed.

Explore

Feminism and architecture

In this lecture video, Susana Torre outlines the powerful, yet often ignored or misunderstood, influence of feminism on architecture and urban planning.

Getting out there and doing

Gregory Melitonov discusses Taller KEN’s design–build program, which brings young architects from around the world to Latin American cities.

Rachel G. Barnard: Transformative justice

Rachel G. Barnard explains her efforts to change the criminal justice system with the Young New Yorkers program.