November 20, 2023

Image credit: Nightnurse Images, courtesy of Magnusson Architecture and Planning PC

Much of the public discussion around fighting climate change emphasizes sacrifice, both individual and communal: giving up meat, flying less, slowing economic growth. But this framing too often conceals the massive potential for positive transformation in the transition to a low-carbon society. Instead of focusing on what we stand to lose, how might we imagine ways to improve our standard of living through the changes required to reverse global warming?

By Sarah Wesseler

Highbridge, a new residential tower in the Bronx set to begin construction in 2024 and open in 2027, makes a strong case that low-carbon buildings can offer a broad spectrum of benefits to individuals and cities alike. Designed by Magnusson Architecture and Planning PC (MAP), which specializes in sustainable housing and community development, the project will far exceed market norms for quality and amenities while drastically reducing emissions compared to baseline code compliance—all while providing affordable homes for hundreds of New York’s most vulnerable people.

Highbridge is among the standout projects recognized by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority’s (NYSERDA) Buildings of Excellence Competition, which seeks to jump-start a major shift toward climate-friendly construction in the state by supporting the development of architecturally significant, low-carbon multifamily residential buildings. (NYSERDA has commissioned The Architectural League of New York to help organize and publicize the Competition.) In 2022, a technical jury for the Buildings of Excellence Competition awarded Highbridge $1,000,000 toward its design and construction costs. Separately, the Buildings of Excellence Competition’s Blue Ribbon Design Jury, which brought together respected designers of multifamily housing, praised MAP’s design for its ambition, thoughtfulness, and dedication to improving the lives of its occupants and the wider neighborhood.

Serving New York’s most vulnerable

The project takes its name from the Highbridge neighborhood of the Bronx, where it will be located. The site sits directly north of High Bridge, which was opened in 1848 to bring water into the growing city as part of the Croton Aqueduct system.

The High Bridge as depicted in a postcard dating from between 1915 and 1930. Image credit: Courtesy of The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, Picture Collection, The New York Public Library

Located on a steep, rocky ledge high above the Harlem River, the property was home to an order of Carmelite nuns until 1983, when it was purchased by Samaritan Daytop Village, a New York City–based nonprofit offering substance use treatment, supportive housing, and other community services. In the decades since, the former convent has served as a home for one of the organization’s residential drug treatment programs. But the building, which dates from the 1940s, was never ideally suited for this use and became more difficult to maintain over time.

Samaritan considered renovating and expanding the convent building, but ultimately decided that, given New York City’s housing affordability crisis, the property would be put to better use with a much larger project incorporating a permanent residential component.

The sizable plot offered important opportunities to benefit New Yorkers in a number of ways, the organization’s leaders believed. At the city scale, it could help address the housing crisis by adding hundreds of new apartments, while at a neighborhood level, it could bring new community-centered resources to an area facing significant social, economic, and public health challenges. And for the individuals Samaritan serves, it could provide a vitally needed resource: affordable, stable, high-quality housing.

“Samaritan’s philosophy is to provide a host of services that address the social determinants of health, and we view housing as key to all aspects of health, improving people’s lives,” said Jerry Mascuch, the nonprofit’s vice president of real estate. “So the idea was to look at this property and maximize the as-of-right development potential to provide as much housing as possible for vulnerable families and individuals.”

Mascuch and his colleagues mapped out a plan to create a new building with 286 affordable housing units—60 percent of them reserved for formerly homeless people—along with 106 family shelter units, an 80-bed treatment center, generous outdoor spaces, and shared community facilities. (The treatment center has since been removed from the project, enabling the inclusion of larger transitional housing units and an increase in the number of affordable housing units, bringing the total to 316.) They envisioned the project serving up to 1,000 people at once, including some of New York City’s most marginalized.

A friendly neighborhood icon

In 2020, MAP was selected to design the new facility through an invited RFP process. The firm quickly began fleshing out plans with trusted collaborators including sustainability consultant Bright Power, landscape architect Terrain-NYC, general contractor Mega Contracting, and MEP consultant Dagher Engineering.

From the beginning, the team drew inspiration from the unique 71,000-square-foot site and its highly visible location. “We knew whatever we did was going to be iconic, and we didn’t want to shy away from that,” said Fernando Villa, MAP principal and design director. “We wanted to offer something that could be in dialogue with the landmark bridge and its tower across the water while also embracing the site’s potential and celebrating everything this building can be.”

But creating a distinctive form was only part of the challenge. To fulfill the client’s goals, the design also needed to be welcoming and approachable—a thoughtful, sensitive presence in the local community. It also needed to maximize the number of residential units, in keeping with New York City’s affordable housing goals, and stay within the existing zoning envelope, thereby preventing a time-consuming land-use review.

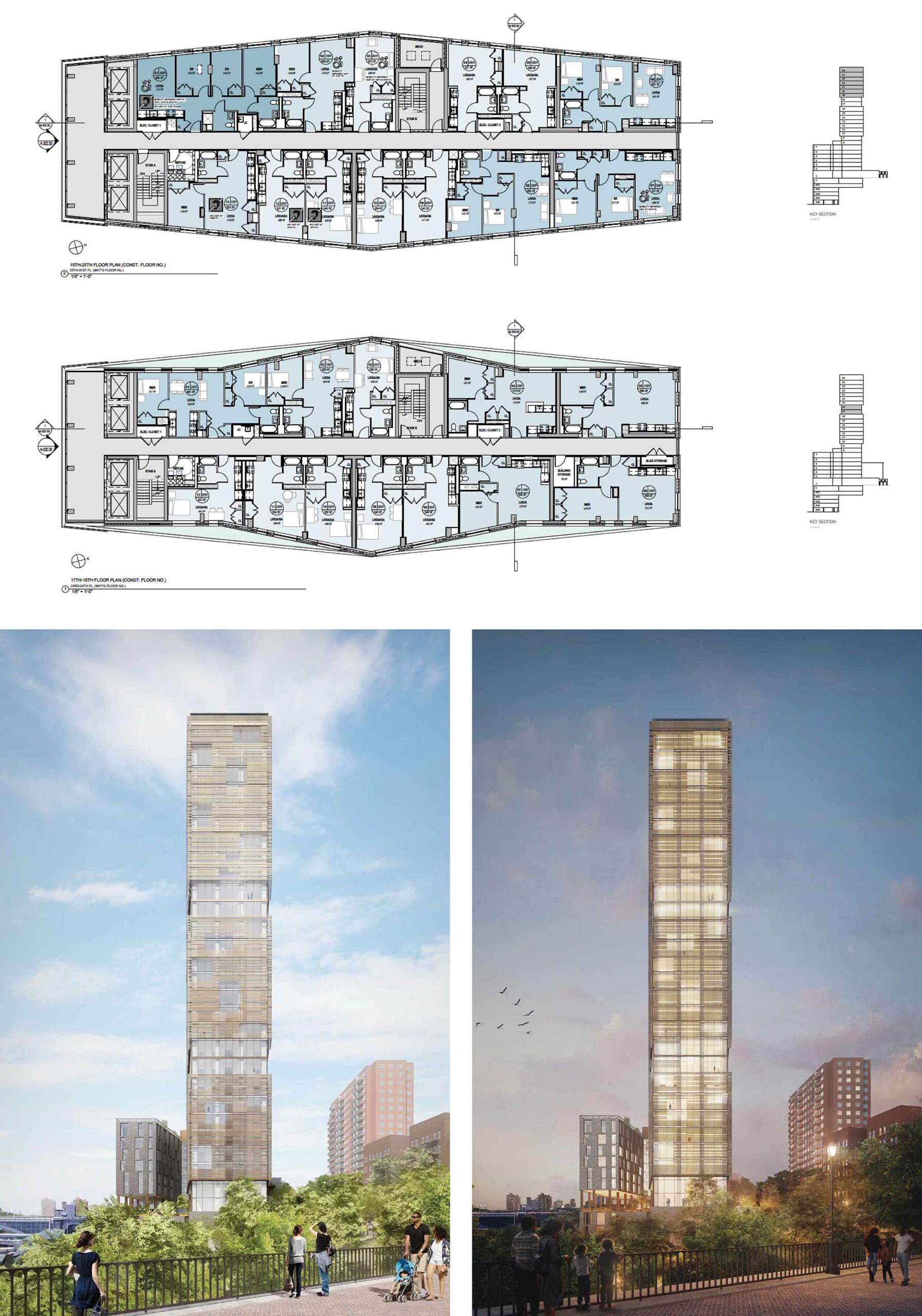

Early massing studies showed that a tall tower with a relatively small footprint was the best way to achieve these objectives. As the design progressed, the building took shape as a 28-story structure with temporary residences on the lower floors and permanent housing above. To prevent the facade from being overly monolithic, MAP created breaks in the massing corresponding to the height of nearby buildings—a visual nod to the neighborhood.

MAP’s early drawings located the treatment center on the lower floors, with the shelter rising to the seventh story and the affordable housing units occupying the upper levels. Generous terraces at the second and eighth stories, as well as a landscaped courtyard at the ground floor, will offer shared outdoor space. Image credits: MAP

The team also sought an optimal balance of density and amenities in the design of the building’s interiors. One solution addressing these goals is the novel circulation in the tower’s permanent housing floors. Taking advantage of spectacular views of the New York City skyline to the south, the architects rethought the standard multifamily floorplate, placing the elevator lobbies at the southernmost tip of each corridor and adding outward-facing seating areas. The reconfigured corridors help maximize occupiable living space, while the south-facing windows provide what Villa calls “a democratic way of sharing” the best views. As an added benefit, the tall column of brightly lit lobbies will serve as a giant lantern for the adjacent Highbridge Park at night.

Top: Typical plans for Highbridge’s permanent housing floors, with the elevator lobbies shown at left. Below: Renderings of the building viewed from the south. Image credit: Top, MAP; Below: Nightnurse Images, courtesy of MAP

Ties to nature are emphasized throughout the project, helping to provide a calming, comfortable atmosphere for residents and the surrounding community. The tower is set back slightly from the main entrance road, allowing the landscaping to wrap around the building and opening views from the street to the site’s existing woodland area. A new semi-public path provides greater access to the woodland while also offering a useful shortcut to Undercliff Avenue to the west.

Left: Highbridge terraces and landscaping. Right: Rendering showing a new public walking path leading from the building’s main entrance on University Avenue to Undercliff Avenue at the bottom of the hill. Image credits: Nightnurse Images, courtesy of MAP

For residents, a generous landscaped courtyard, second walking path, and multiple terraces offer additional opportunities to spend time outside, exercise, and interact with neighbors. Early plans also envisioned an urban farm with composting facilities and chicken coops.

Renderings of Highbridge terraces, landscaped entrance, and resident-only walking path. Image credits: Top four renderings, Nightnurse Images, courtesy of MAP; Bottom two renderings, Terrain

A 360-degree approach to sustainability

Sustainability—and, in particular, climate mitigation and adaptation—has been key to the project from the outset. According to Samaritan’s Mascuch, while the organization has historically been committed to environmentally friendly design as a matter of principle, trends in the affordable housing sector have increasingly made it a matter of pragmatic self-interest. Because the New York City government requires new affordable housing construction projects to comply with the national Enterprise Green Communities Criteria standard as a condition of financial support, failure to consider issues like energy efficiency would have jeopardized $80 million in funding.

Furthermore, the increased policy focus on decarbonization meant that cutting corners during the building’s creation would likely necessitate significant retrofits down the line. “We want to make sure Highbridge is a long-term asset for Samaritan and the community that is both sustainable and feasible,” Mascuch said. “We really want to build something that’s anticipating the next 20 to 30 years of regulations.”

Although the project team is pursuing a broad variety of solutions to achieve this goal, the most impactful is the combination of electrification and passive house design, according to Sara Bayer, MAP associate principal and director of sustainability. “The best way to decarbonize is with an all-electric passive house [building],” she said.

The all-electric half of this equation is quickly becoming standard practice in New York State thanks to Albany’s recent passage of a law mandating that most new buildings move away from fossil fuels as of 2026 (or, for larger structures, 2029). But the passive house component is still relatively rare for tall projects in the United States.

Working closely with Bright Power, Bayer has led the effort to tailor Highbridge’s design for eventual Passive House certification. Having designed several passive house projects with the Highbridge consultant team, she believes the standard offers several advantages over LEED. The first is predictably low energy consumption for the heating and cooling systems, a function of an airtight envelope that reduces unwanted transfer of heat between interior and exterior. Unlike LEED, the passive house standard requires testing of a building’s air barrier, which is the gold standard for providing reliable information about energy savings for mechanical systems.

According to Bayer, while a LEED Platinum building might be expected to cut heating and cooling energy consumption by approximately 25 percent compared to code, a passive house building could realistically achieve a 60 percent reduction. For Highbridge, calculations made early in the design estimated that a passive house approach would reduce power needs by 80 percent compared to the 2019 New York City baseline.

The second major advantage of passive house design over LEED is improved indoor air quality, Bayer said. Unlike LEED, Passive House certification requires the use of energy recovery ventilators (ERVs), which continually pump fresh air into airtight buildings. “I don’t think we’re getting healthy air without them,” she said.

For the Highbridge team, careful consideration of the relationship between planetary-scale environmental challenges and the wellbeing of occupants is key to the project. “In a lot of the communities we work in, particularly in the Bronx, the health statistics are particularly bad as far as asthma and things like that,” said Samaritan’s Mascuch. “Our approach is to address the whole person, and for someone to get their substance use under control, to get their family life in better shape, their kids attending school, all that is helped by a healthy living environment.”

Occupant wellness is also a major consideration in the material selection process. “All our specs are going to be guided by the use of healthy materials—very, very low VOCs [volatile organic compounds], a lot of recycled content,” said Fernando Alvarez, MAP’s technical director. Cutting-edge options like bacterially grown interior tiles are being considered alongside common materials like mineral wool insulation and wood flooring.

Other sustainability solutions planned for Highbridge range from rooftop photovoltaics and heat pumps to low-flow plumbing fixtures. Many of these have become fairly common in New York in recent years, according to Bright Power’s Carmel Pratt, but a few are still making inroads in the local market. One, the PIRANHA system, uses energy captured from wastewater to generate hot water. Another, recycled foam glass sub-slab insulation, is a low-embodied-carbon substitute for standard gravel and insulation that is widely used in Europe but less commonly specified in the United States.

Many of these design features also convey significant resilience benefits. The high-performance envelope and efficient building systems will provide comfortable interior temperatures during heat waves and cold snaps while minimizing stress to the city’s power grid, while shaded, landscaped terraces will offer outdoor respite on hot days as plants cool the surrounding air through evapotranspiration. The airtight building envelope and energy recovery ventilators will provide high-quality indoor air during periods of outdoor pollution produced by wildfires and other air pollution events, while the absence of onsite fossil fuel combustion will leave the surrounding air cleaner.

The landscape design has also been carefully planned with stormwater in mind, seeking to avoid adding to the challenges extreme weather events pose for New York’s sewer system. “We’re adding bioswales, permeable paving where we can, and then forming pockets of planting that can help capture and slow down stormwater,” said Steven Tupu, founding principal of landscape design firm Terrain.

To safeguard occupant health during heat waves and grid failures, the building will also house three cooling centers. The project team originally planned to power these spaces via a battery-powered emergency generator but found that the technology and regulatory environment aren’t ready for this step. “The battery part was the size of an 18-wheeler,” said MAP’s Alvarez, “and the fire department is still not there.” As a result, the emergency generator will run on gas—the only part of the building to do so.

Making sustainable design a reality

While challenges around technological maturity, material availability, financing, and a hesitancy to embrace change among some suppliers and subcontractors have arisen throughout the project, MAP and its team have found ways to keep most of the sustainable design features intact as the design has progressed.

In part, this has been possible because the individual components of Highbridge’s sustainability plan are relatively straightforward and easy to achieve within the current New York market even though the full scope is exceptionally ambitious. And while some green features come at a premium, the price differential often isn’t as high as commonly assumed.

“There’s still this misconception that, for example, a passive house costs up to 30 percent more to construct, but we know that’s not true, and we have data to back it,” said Bright Power’s Carmel Pratt. Having team members on board who understand the true cost of sustainable design features and can make a strong case for a return on investment is critical. “That’s where I see our role coming in—to help push forward those ideas,” said Pratt.

Sara Bayer plays a similar role across all of MAP’s projects, championing sustainable solutions and educating others on best practices. She believes that developing in-house expertise in passive house and energy modeling, in particular, can go a long way toward helping firms develop more environmentally friendly projects—and stay competitive in a fast-changing business environment. “In New York City, we’re going to have performance-based code in 2026, so that means energy modeling. I don’t think architects are ready to put their stamp on energy modeling,” she said. “It’s clear—or should be clear now to architects who are paying attention—that they need some expertise [in these areas].”

One low-cost, high-impact method the Highbridge team has employed to improve sustainable design outcomes is integrated design. For MAP, convening a broad group of stakeholders in a project’s initial phases is standard practice. “One thing about working with Fernando Villa and their team is really being part of the conversation really early on, before anything is formed on paper,” said Terrain’s Tupu. “And that comes down to doing a first site walk together, [with] both teams onsite, having these initial ideas before any one team starts to cook anything. I find that really potent for the team as a whole, rather than ‘the architect develops the massing and it’s done, and later down the consultants get plugged in.’”

Another cost-effective means of developing stronger, more impactful sustainability plans is to maintain a tight focus on the needs of the people a project will serve, said Bright Power’s Pratt. The Highbridge project team has a strong understanding of how intertwined challenges of environmental hazard, public health disparities, and social and economic marginalization shape the lives of vulnerable New Yorkers, enabling it to tailor its design for maximum impact.

For Samaritan’s Mascuch, keeping future residents at top of mind throughout the process is personally rewarding as well as strategically vital. “It’s really exciting when you open up, you see people moving in,” he said. “That’s just one of the most gratifying experiences.”

Explore

2023 Architecture + Design Independent Projects Grant Recipients

In the second year of the League’s Independent Projects partnership with NYSCA, 25 design proposals were selected for grants of $10,000 each.