In conversation: Mariana Ibañez and Simon Kim with Elissa Goldstone

The winners of Folly 2015 engaged in an email conversation with Elissa Goldstone, the exhibition program manager at Socrates Sculpture Park.

Elissa Goldstone: Before we talk about Torqueing Spheres, let’s chat about the Folly program more generally. How does IK Studio define a folly? And has that definition changed or expanded within the context of the League and Socrates’ Folly program?

IK Studio: Follies, as we studied them, were part of an English landowner’s estate in the 17th century, much like ha-has and grottoes. Follies are buildings made for scenography, to be looked upon as part of a larger tableau. Tied to the aesthetics of the picturesque and the beautiful, they are often associated with period styles and even mannered — to look ruined, for example.

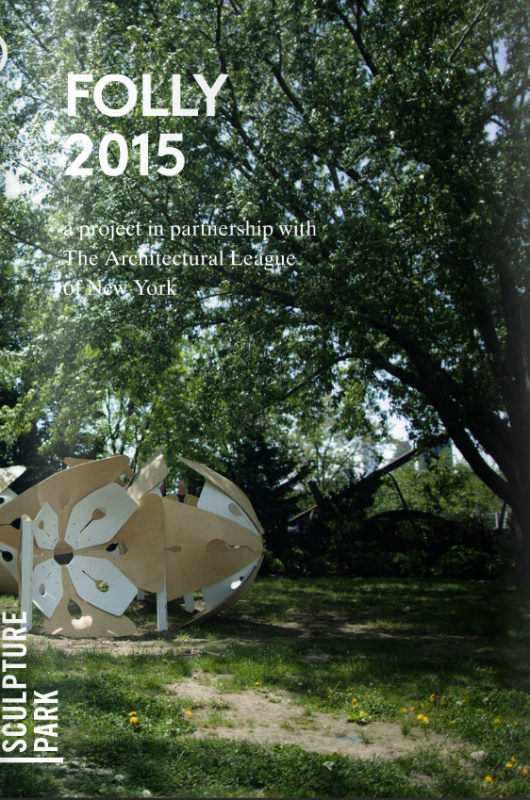

For us, follies are better associated not with private estates and wealthy landowners, but as open public things for the pleasure of the citizens in a city. The appeal of making Torqueing Spheres on the grounds of a public park like Socrates was to extend a social element to an accessible material like wood. We have witnessed the formal play between the installation and the young families, teens on bikes, and many dogs over the summer. We also like the views the park affords across the East River to Manhattan.

We love the idea of a folly as an architectural tradition and its broader meaning as something that defies accepted logic. It speaks of frivolity, some mania, and also an opportunity to experiment or try something unusual.

Much of architectural production does not allow for risk or chance — I don’t know of many paying clients who would be happy with error. And academic research does not often leave the lab or the school environment. Follies, unlike pavilions, are perfect venues for private obsessions played out in the public realm.

Goldstone: I’m always curious how a final design scheme comes together. What led to your Torqueing Spheres proposal for Folly, and then how was the design realized?

IK Studio: We were intrigued by the overlap between design and art in the competition’s partnership between The Architectural League and Socrates Sculpture Park. The possibilities of what the Folly could produce fit well with the conceptual project of our office. We defined parameters — both formal and social — and made catalogs of types. From these, we became interested in domes that are turned sideways and connected in a bent line. They are still structural, but counter to their local lines of force (from oculus to shell to vault), they are self-supporting as an aggregation of connected domes. We made several full-scale prototypes to study aesthetics and structural performance.

With structural analysis, these become part of a larger live load study of the impact of lateral winds and human interaction. Our consultants at Buro Happold were great at dialing in offsets, material thicknesses, and maximum spans. One necessary concession is the steel posts to keep it in place — the folly would stand on its own as a monocoque system, but would be blown about by the wind.

Goldstone: It seems like your primary focus with Torqueing Spheres is a material investigation that (in its most reduced definition) manipulates planar sheets into curved forms. What’s your interest in this formal manipulation?

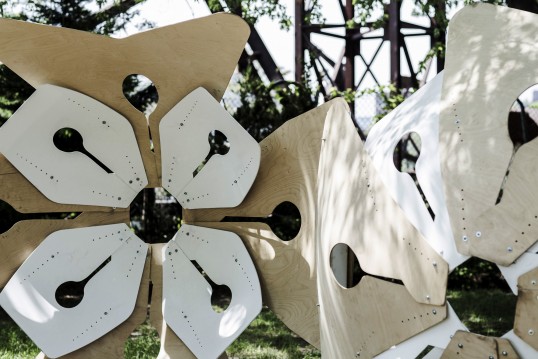

IK Studio: We discovered that cold-bending plywood produces several physical and mechanical results. The first is that the resultant geometry is not conic, as produced in isotropic materials like film or plastic sheets, and is therefore not easily digitally simulated because bent plywood has double curvature due to the cross-grain in the ply. Secondly, cold-bent plywood is exceptionally strong due to its stressed and rigid surface when locked in place. Finally, because of the way in which it is produced (veneers are cut parallel to the pith of the log), plywood that is cold-bent will continue to bend in the same direction when exposed to water vapor. This is a very interesting phenomenon, called a compliant mechanism, which causes the domes to contract over the hours of a humid day.

More importantly, wood is supple and soft and a material that people react warmly to. In this formation, of a dome with an oculus, the wood frames views and bounces sound. At the opening we saw adults and children peering through (and sometimes climbing over) Torqueing Spheres as well as testing the echoes. The spheres are very deep and the space within each shell is volumetric, although we removed our initial idea to have benches inside. In the overall configuration, the spaces follow an inside–outside line that looks outward to the river and inward to the park and the other artworks.

Goldstone: Tell me about IK Studio. What defines your practice? I’m especially interested in the timeline and history of your studio. You are husband and wife, academics, and architects — which “practice” came first?

IK Studio: Great question. We draw careful distinctions in our respective domains that we periodically check for accuracy and direction. IK Studio officially started in 2012, the year we received our Green Cards. Before that we were full-time faculty and researchers, Mariana at Harvard University and Simon at the University of Pennsylvania. We worked in different countries for several years, for both others and for ourselves, before coming to the US.

What we do in our practice and academia is a parallel arrangement of research at the highest institutional levels. These findings and initiatives are then substantiated as architecture and made public by our design practice. Then projects in the office are continually reflected back to the lab and academies, which has proven to be an effective engagement.

Goldstone: You referenced research as the bridge between your teaching and practice. What is the subject or emphasis of your research?

IK Studio: The Immersive is what we are calling our research agenda and conceptual project. We promote an activated urbanism and architecture that can no longer be critically distinguished as subject and object: we are immersed and engaged in environments where other, nonhuman agencies have equal authorship. We continue the provocative work of New York’s E.A.T., the Architecture Machine Group (before it became a media lab), and others like Cedric Price and Hans Hollein. The work they were producing was so future-forward that it still resonates today. But what has changed is that all the electromechanical componentry that was largely unavailable then is freely accessible now.

Torqueing Spheres is an important milestone for us. It is also our first foray into large-scale compliant mechanisms that are bio-actuated — the wood bends without electrical current and in response to meteorological conditions, like temperature and humidity. We’ve worked with shape-memory alloy and polymers, as well as soft robotics, but this folly is the largest and most robust.

Goldstone: I’ve heard you mention that this process of bending planar material is only possible through an analog investigation and that there are (currently) no methods to digitally simulate this process. How does this impact the working process?

IK Studio: This is the big divide of analog from digital. It is not possible for material properties to be computer simulated in high fidelity. The qualities of any matter — its grain, internal stresses, atomic structure — change from piece to piece. Annealed glass is different from float and tempered steel from case-hardened. An organic material like wood is no different. Each tree grows differently and won’t be the same as another, even if of the same species. But enough similarity is there to allow for some predictive modeling; otherwise we would all need to be highly trained craftspeople working intimately and at small-scale. There is no “bent plywood module” in software like CATIA, however, so we worked digitally in ideal geometries and then tested in full-size mock-ups.

Photo by Kordae Jatafa Henry

Goldstone: Which architects or artists informed your thinking for Torqueing Spheres? Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes come to mind, and I’ve heard you mention Frank Gehry. Any others? And if so, how do they shape your processes and investigations?

IK Studio: For modern domes, we looked at Buckminster Fuller and saw that he had patented a self-strutted “plydome.” The panels are largely rectangular but follow icosahedron logic, getting joined where they overlap. That didn’t really appeal for what we wanted to achieve. For us, immediate influences are the people with whom we’ve worked: Zaha Hadid, Frank Gehry, and Cecil Balmond. Their creativity-with-rigor is something we apply to our practice.

Goldstone: “Creativity-with-rigor,” I like that. So lastly, what’s next for IK Studio? What projects or experimentations are you looking forward to?

IK Studio: We are getting busier! We’re engaged in some National Science Foundation-funded research work and at the building scale we have several projects underway — a church, a daycare, and a tree house.

We just completed an installation at the BSA Space where we made a room within a wall as part of a larger exhibition called Bigger than a Breadbox, Smaller than a Building. We are also pleased to tell you that a public art organizer saw Torqueing Spheres and invited us to be part of The Lawn on D summer programming in Boston. There’s also a larger group of pop-up objects and spaces we are developing for the Beakerhead Festival in Calgary this fall.

Goldstone: That all sounds exciting and seems to operate within the investigatory realm that Folly encourages — between sculpture, architecture, and public art.

Torqueing Spheres was designed by IK Studio: principals Mariana Ibañez and Simon Kim with support from Chris Johnson, Iman Fayyad, and Charlotte Lipschitz. Structural consulting by Gustav Fagerström and Michael Steehler of BuroHappold. Fabrication by Tietz-Baccon. Recycled material from William Blaise Dufala and RAIR Philly. With support from PennDesign and Harvard GSD.

Folly is a competition co-sponsored by The Architectural League and Socrates Sculpture Park that invites emerging architects and designers to propose contemporary interpretations of the architectural folly, traditionally a fanciful, small-scale building or pavilion sited in a garden or landscape to frame a view or serve as a conversation piece. The Folly 2015 winner was Torqueing Spheres by Mariana Ibañez and Simon Kim of IK Studio. Ibañez and Kim conducted an email interview with Elissa Goldstone, Director of Exhibitions at Socrates Sculpture Park, on their definition of a folly, their “creativity-with-rigor” approach to projects, and what’s next for IK Studio. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Explore

Folly 2015: Notable entries

Sophie Elias surveys themes that emerged among the 2015 Folly submissions.

Dynamic mediums: The design and fabrication of Torqueing Spheres

Delve into the design, materiality, and fabrication of Torqueing Spheres through a process photo essay and interview with designers Mariana Ibañez and Simon Kim.

Folly 2015: Torqueing Spheres

A look at the winning entry of the Folly 2015 competition.