For Lola Ben-Alon, a Lab is a Dirty Place

Lola Ben-Alon discusses mixing ritual, history, and structural innovation at The Natural Materials Lab.

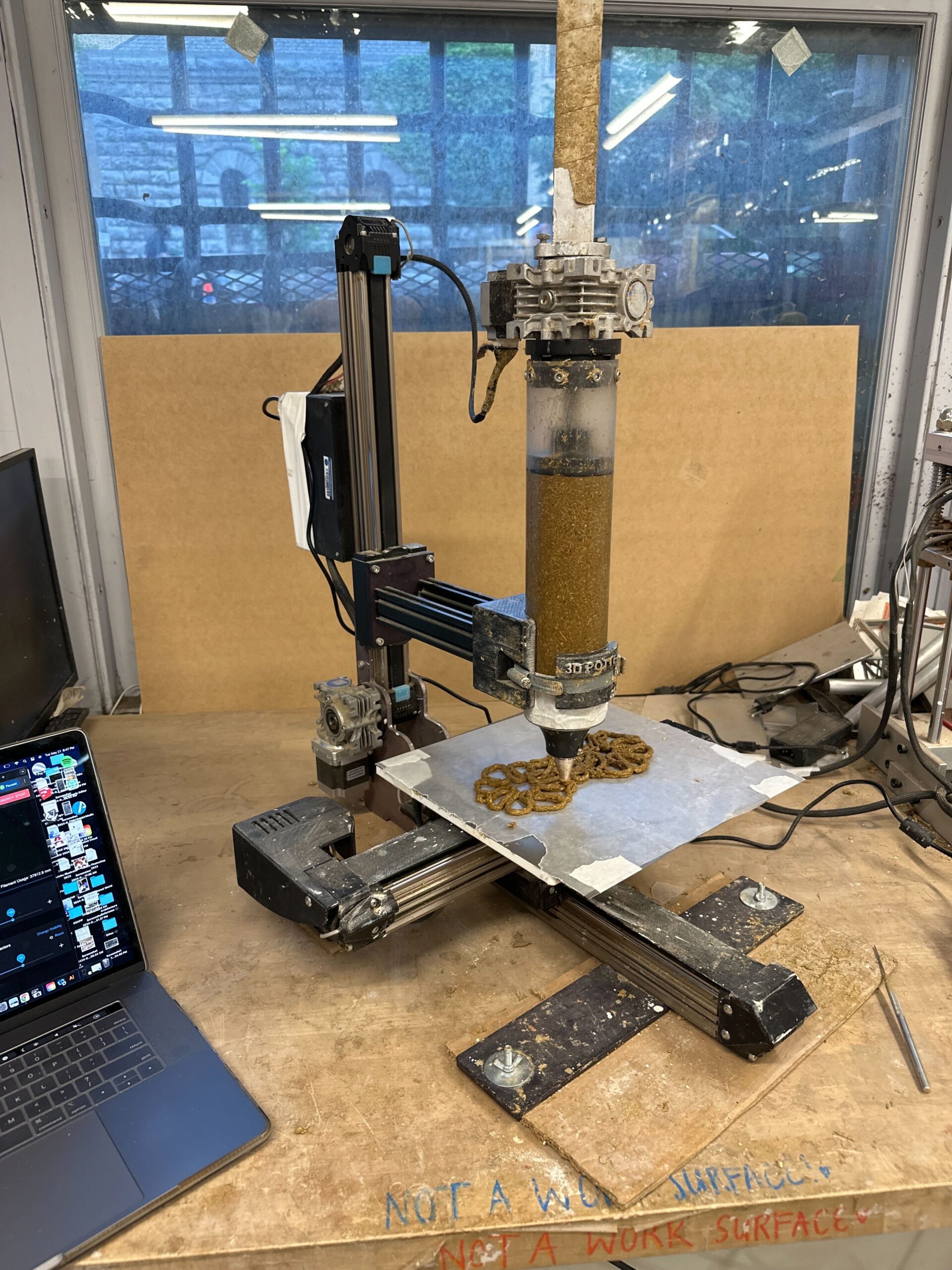

The Natural Materials Lab, founded and directed by Lola Ben-Alon and located at Columbia University, investigates raw, earth, and fiber-based building materials across scales, integrating emergent technologies with historical techniques. For her League Prize installation, Ben-Alon documented the process of printing mud bricks for the Lab’s show at AIA Houston’s Big, Hot, and Sticky exhibition.

The League’s Anne Rieselbach spoke with Ben-Alon about documenting the “dirty” processes of the Lab, from the technical difficulties of 3D printing mud to surface cleaning protocols, as well as Ben-Alon’s engagement with ritual and feminine collective practices for building with natural materials.

*

Anne Rieselbach: It may seem self-evident given the primary building materials you work with, but could you describe how you conceived your installation concept in response to the theme of “Dirty?”

Lola Ben-Alon: What I tried to do in the installation was to show the behind the scenes of the lab. Labs are categorized by their cleanliness; there are certain conditions you need in scientific labs in order to have the necessary sanitized environment. And one of the things that is a kind of “impediment” at the Natural Materials Lab is that it is very dirty: we shred fibers in the space, we sift soils, we make with dirt. So I constantly ask: How do I work with the dirtiness of the lab space?

We have all these protocols at the Lab that are taken from different disciplines that work with dirt, clay and matter. One of the protocols that I use, for instance, comes from pottery studios. In pottery studios, when you wash your floor, you want to mop rather than sweep so you don’t get airborne particles. When it came to growing mycelium at the Lab, it was so challenging that the research question navigated to being: How do we make “dirty mycelium?” How do we grow mycelium within substrates that have fiber and cellulose, but also soil, mud, and dirt? So in relation to this theme of dirtiness, I wanted to show exactly that: the Lab, our processes, the behind-the-scenes.

Rieselbach: In your portfolio you described your work, in part, as “confronting dichotomies between ‘high-tech’ and ‘low-tech’ design methodologies, working with materials that are rooted in our collective embodied experiences and histories.” What inspired you to explore historic, tactile, and even sensory aspects working with earth and plant-based materials that reach beyond more familiar work in the field that primarily emphasizes exploring structural possibilities for 3D printing using earth-based composites?

Ben-Alon: It’s interesting because during my PhD, I used the time and the resources I was given to travel a lot to building workshops: rammed earth, clay plaster, earthen floors, you name it. I even participated in a two-week workshop for building a cob structure from foundation to roof. And one of the things that I learned from participating in these DIY events is that you can’t own earth materials because everyone learns the techniques rather quickly. It’s so accessible, and the reason it is accessible, I think, is because each of us probably has ancestors who’ve worked with this material. So, I truly believe there is some memory, some somatic memory, of us working with these materials, making it very accessible for us to gain knowledge and own this way of building pretty quickly.

Rieselbach: What are some of the historical references beyond aspects of earth as a building material that inform your work?

Ben-Alon: I’m really curious these days about how clay-based practices came to be before burning materials started happening, beyond what Western scholarship on archeology tells us. There’s so much more to traditional histories and knowledges. If you look at the pre-pottery Neolithic period in Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean, practices of using clay in its raw state were applied in everyday life, not only in making a brick for your building but also for ritualistic practices and figurine-making. Traditional texts show that there were “central pits” in a village that everyone drew from to make everyday objects. I’m really drawn to learning, reading, writing, and understanding more about these histories of building materials, because essentially we keep seeking the same things: to work with matter that is a primal binder, not only materially-speaking but also as a facilitator of human interactions and understanding of self.

Rieselbach: Are there formal implications of these precedents? And if so, how have they shaped your work?

Ben-Alon: One of the things that we’ve been doing is 3D-scanning objects from the Neolithic period and translating those scans to 3D-printed objects. What does it mean to speculate on another dimension of making? This work was exhibited recently at the 2024 Indian Ceramics Triennial in January, and we’re now writing an essay in collaboration with a curator at the Near East Gallery at the Metropolitan Museum. I’m fascinated to see how objects evolve from rituals to artifacts and then to architectures, because I truly believe that we’re looking at a period where, globally speaking, there should be a more unified approach to making: the making of our buildings, the making of our food, the making of our objects should be more enmeshed, as it was in our past.

Rieselbach: The text for Material Kitchens for Medicinal Bricks describes infusing clay soils and plant fibers with medicinal resins and salts and materials to create 3D-printable concoctions. Could you describe some of these additions, how you determine the final mix for the bricks, and also the composition of the medicinal resins?

Ben-Alon: At the Lab I sometimes feel we act like chefs. We make recipes, we test recipes. It’s a very iterative process where you change one component of the mixture at a time, increasing or decreasing a certain constituent and changing ratios. It’s very systematic work, and for 3D printing, it’s a work that requires rheological testing, extrudability, buildability, there are technical requirements for certain mixtures, very similar to how there are certain requirements for a mixture to be molded into a brick or to be spread as a render in 3D printing.

It is also a very magical process. Here we added B’hur which is a really special aromatic mixture of plants, resins, and minerals. It’s used by Sefaradic Jews, especially those born in Morocco, to cast the evil eye and bring blessing. The idea was to add it to the bricks and burn them as an act of ritual. What we do at the Lab sometimes feels very ritualistic. There’s a certain workflow with the researchers and student assistants. It’s almost devotional, because it’s so hard to work with these materials. They’re very labor-intensive. With the tactile experience, doing this work is very transformative.

Rieselbach: What was the formal inspiration for the multi-lobed, almost flower-like form?

Ben-Alon: The work represented in the League Prize installation was for an exhibition in Houston titled Big, Hot, and Sticky, referring to the city and its climate. The shape was derived from investigating air movement through circular geometries. We investigated different phenomena, one of which was a really interesting phenomena called the medicine wheel, a typology made in and with nature by Native American people. Near Houston, there is a specific medicine wheel associated with the Tonkawa, Comanche, Kiowa, and Waco people of the plains of Texas: the Leon River Medicine Wheel. We found fascinating documentation of the scans of the stones and the arrangement of earth elements to create this medicine wheel arrangement that is used not only for cultural gathering, but also for rituals and religious practices to bring healing to the people and land.

We also thought about what it means to blow air through a certain geometry. Beyond the bioclimatic effects of cooling, the interaction between the air and the space helps the intention within these objects flow and move, much like in Tibetian prayer wheels. So it started with the medicine wheel, but then we learned about similar geometries that act in circularity and reflected on sacred shapes in religions across cultures and geographies such as the Japanese Enzo, the Kabbalah Tree of Life, and the Hausa Arewa Knot.

Rieselbach: How do you balance creating structural integrity of the bricks with all these inclusions and materials?

Ben-Alon: We started working with a brick that was intended to be used modularly. Then we found that during the printing process, the bricks dried in a certain way that made them very tapered at the bottom—the bottom surface had shrunk less because it had less contact with the air. Stacking the bricks on a vertical orientation was challenging because the tapered shape of the bricks created a very tapered wall. We thought about different connection mechanisms, but eventually we realized it might not be structurally sound, so we ended up finding a way to stack the bricks diagonally to create pillars. The moment that we realized this possibility was such a joy. Finding the right arrangement of the brick, or how the brick wants to be arranged, was really interesting.

Rieselbach: What did having the chance to produce this installation offer to your practice as a whole?

Ben-Alon: It really allowed me to focus on the “how” instead of the “what,” which I constantly strive to do not only at the Lab but also in my courses. How are things being made? I think that is a really important question, especially in our field. I have that problem too, and I see it with my colleagues when we give our presentations with all these wonderful, wonderful installations and work and pavilions. But behind every successful project there are so many “dirty” iterations and so many wonderful failures that we never show. And then I’m very appreciative of the opportunity to go a little wild with the medicinal application, because I really see processes in architecture as embodying personal and collective rituals, and I wish to bring more of that into this space.

Rieselbach: What are you working on now?

Ben-Alon: I’m writing one book and editing another. The editorial volume is titled Material Variance, after a symposium I led at GSAPP. It is a wonderful collection of essays and articles by scientists, artists, and material research designers who are pioneering different notions of how materials should be viewed from historical and futuristic perspectives. And the book I’m writing deals with earth and fiber materials in architecture.

The Natural Materials Lab is also going to show Muddy Stools at the Material Matters fair at the London Design Festival in September. The muddy stools, commissioned by GSAPP, are made from a mixture that include horse manure, so they have some mud but also some stool in them. We will also be showing our Weaved Lattice Structures in Material Act, an exhibition forthcoming in October at Craft Contemporary museum in Los Angeles.

Interview edited and condensed.