Flash and spectacle in the face of austerity

Anya Sirota discusses the relationship between architecture, culture, and urban vitality.

An interview with Anya Sirota, a partner at Akoaki and a recipient of the 2018 League Prize.

How can culture strengthen cities, and what role should designers play in this process? Anya Sirota and her partner Jean Louis Farges have spent the last ten years exploring these questions in Detroit.

Sirota spoke with the Architectural League’s Catarina Flaksman and Antonio Huerta about her work.

*

Catarina Flaksman: Can you talk about your approach to architecture and the cultural references behind your designs?

Anya Sirota: I graduated from architecture school in 2008 and entered the field at that difficult economic moment. I moved to Detroit, where my partner and I were surprised and affected by the level of economic degradation. We very quickly started to explore new radical models of practice that move beyond traditional forms of patronage. That’s been the crux of our work.

Unlike a standard design service, which begins with a site, a program, or a client, we’ve spent our time proactively looking for ways we can instigate projects, activate sites, invite clients, formulate necessary programs, catalyze networks of people, and secure external funding. And all of this happens before the design concept even begins to take form.

The back end of what we do is pretty robust in order to produce joyful, ornamental, vivacious, and maybe even blingy results in scenarios where the capital might be missing but the cultural drive is alive.

We’re sensitive to the idea that a context can produce novel aesthetic sensibilities. We’re culling signifiers, textures, ideals, and collective imaginaries from wherever it is that we’re working. There isn’t a specific aesthetic agenda preceding our projects. We uncover them by working really intensively in a given context.

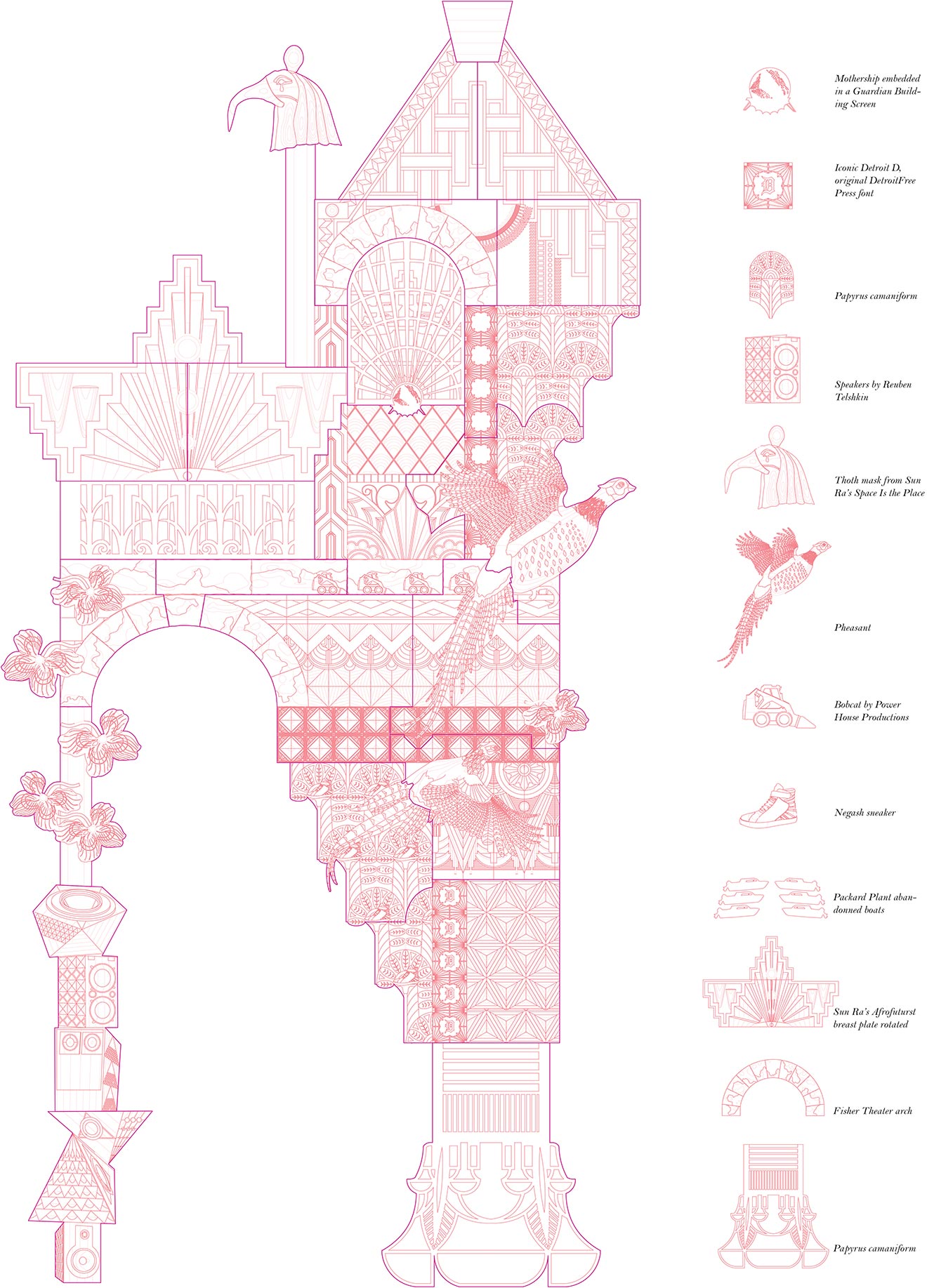

In Detroit, there’s a very strong relationship between an Afrofuturistic ethos and the experimental vanguard aesthetic associated with funk music. We’ve tried to bring those to the forefront of our work. In the Nomadic Detroit Culture Council project, the gold finish, the symbols, the winks at a kind of fictionalized Egyptology, a love affair with Sun Ra’s Space is the Place, and the missing pieces of architecture that have fallen victim to aggressive blight remediation campaigns find their way into our design.

The Nomadic Detroit Culture Council’s gold arch references the city’s popular aesthetics. Credit: Akoaki

Flaksman: What does your work process look like?

Sirota: With these projects, it’s pretty much impossible to create the networks of people, the programming, without consistent presence in the field, and Jean Louis is consistently present in the field. I spend more time on the design aspect, on aesthetic representation and form-making.

Flaksman: Can you tell us more about the Nomadic Detroit Culture Council project?

Sirota: A lot of cities have an official arts council, recognizing that art and culture are significant drivers in creating and redeveloping cities, but Detroit no longer does. Yet artists have such an important presence and do so much independent groundwork here. They’re splintered, sometimes unaffiliated, and there are no municipal organizations that advocate for their rights. So we became involved with different groups of artists interested in bringing an arts council back to Detroit.

We’re very excited about the possibility of designing parallel institutions. We thought that if we created an institutional signifier that could clip onto any vacant or underused building, we might be able to catalyze a conversation about the potential of an official arts council.

Working with those artists, we culled a series of signifiers. My undergraduate degree was in semiotics, and somehow it found its way into my architecture practice. We looked at artifacts that local creative practitioners were making, from sculptures to sneakers and other vernacular objects. We designed a mashup, adding architectural elements from people’s favorite buildings in the city. The result is an arch which is light and replicable.

It’s made of molded plastic and paint, but we tried to make it look as dignified, surreal, and institutional as possible.

We started clipping the arch onto existing buildings, and to our great surprise hundreds of people showed up to participate in conversations related to arts, culture, and equitable redevelopment in Detroit.

At this point, the City has started looking into what a new Detroit arts council might look like, and some of the people involved in these early conversations are probably going to continue being part of that discussion.

Antonio Huerta: What led you to think and work this way, connecting architecture and social engagement?

Sirota: We’ve looked with affection to social practices in Europe. We’re big fans of Patrick Bouchain and his work with Construire. There’s a whole slew of younger design firms whose work has a relationship to pageantry, social possibility, and untethered self-expression in the urban realm.

The difficulty of replicating that kind of work in the American context, specifically in cities with significant economic challenges, is that there are few capital resources at the public level. We have to find alternative funding. So we’ve looked at European models for creating social vivacity in the urban realm, and then tailored them to the realities of our context.

Why we do the things we do… I’m a Soviet refugee, old school. My family moved to beautiful Providence, Rhode Island, when I was six. So I come from a place where history was often erased through aggressive iconoclasm. My partner is a working-class Parisian who’s very sensitive to issues of class, race, and identity.

Building on our idiosyncratic experiences and mutual political affinities, we’ve looked for playful ways that architecture can participate in public discourse, without being didactic or turning to the conventional visual tropes associated with social justice movements.

I don’t know if our past experiences have influenced our interest in design so much as they’ve prompted an affection for flash and spectacle in the face of austerity. Of course, our background has also made us keenly sensitive to the situational aspects of architecture. We treat our work as a staging ground for human experience, calibrated for inclusivity and permissiveness.

Huerta: You teach at the University of Michigan, which is known to have a strong maker culture. How does that affect your work?

Sirota: The school has one of the most incredible fab labs. As faculty, I benefit from access to machines, tools, resources, amazing colleagues, and support networks that make these kinds of experimental projects possible.

Sure, we’ve been building parallel, quasi-institutions in Detroit, but it would be impossible without a real institution backing our efforts.

Flaksman: Going back to the idea of keeping the memory of a place, do your projects transform their context in some way?

Sirota: We’ve always been interested in this idea of hauntology from Jacques Derrida, who suggested that it’s impossible to go back to an original signifier, but as long as people have a sense that there’s a layering of time, something profound can happen in cognition.

We really believe that. Rather than being nostalgic and rebuilding signifiers that people can clearly identify as being of a particular time, we’re trying to be mixologists of aesthetic value.

Some groups in Detroit have preferences for a particular moment in the city’s history. In downtown or Midtown, everything points to an aesthetic from the ’30s or ’40s: a kind of pre-African American urban condition.

It’s important to us not to work with aesthetics that can be misinterpreted as nostalgic. At the same time, we don’t want people to feel like something alien is coming into a particularly stressed-out context. We want people to feel something of a collective cultural imaginary, even if it’s a bit foggy.

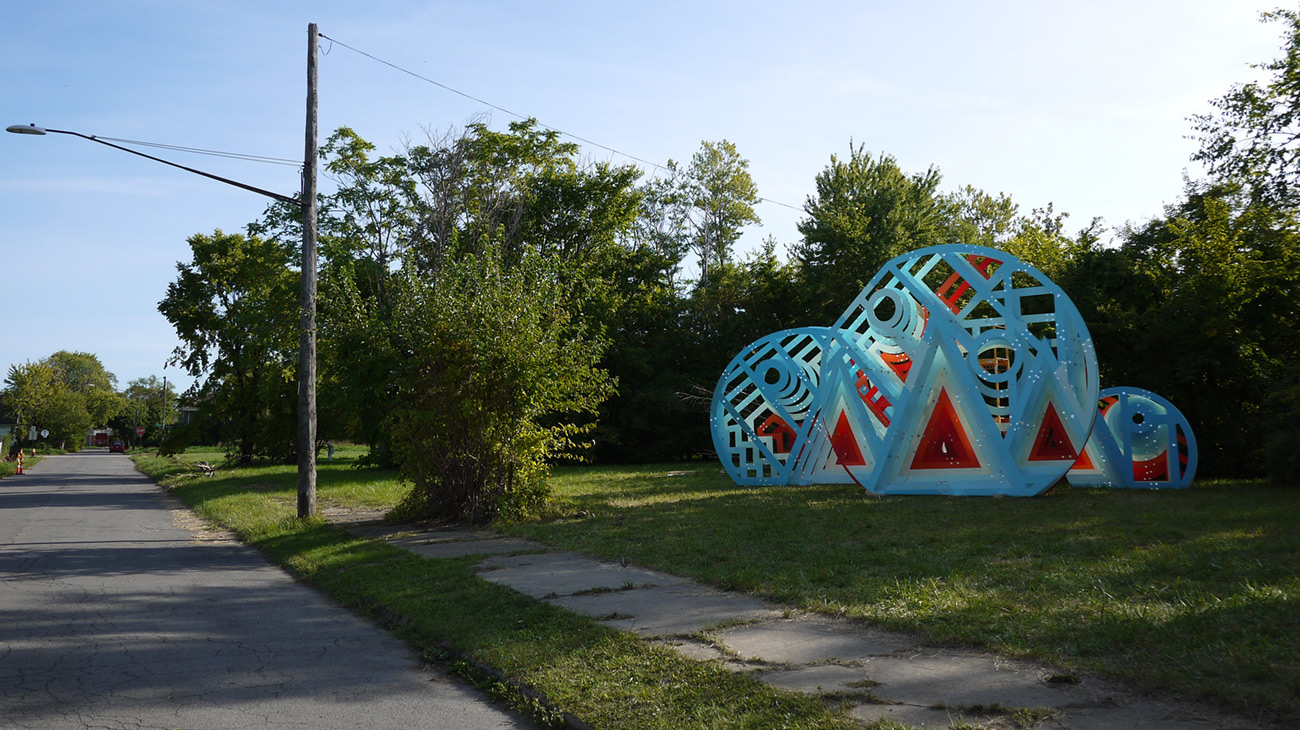

We built a set for the Detroit Afrikan Funkestra, an open-air opera at an urban farm, and we sampled every color of every stage set in the neighborhood, then combined those colors and shapes to produce a new mashup. The folks who were there couldn’t say directly where the signifiers were coming from; it felt new and pop and exciting. Yet it was slightly familiar. That’s the kind of vibe we’re aiming for. That’s where we think exciting, pluralistic, social, and untethered collective expression can happen.

Detroit Afrikan Funkestra installed at the Saint-Étienne International Design Biennial in France, 2017. Credit: Anne-Laure Lechat

Flaksman: What’s your research process like?

Sirota: We’ve been asked if we do participatory design: if we bring everyone together and listen to all of the stories and then put together something in response. But that’s not quite the case. We’re more formalist than that.

For example, when we designed the Mothership, we looked at every single funk album that was produced over the span of 20 years and combined the patterns we found to make something that we thought was appropriate. And then we looked at every color of gold vinyl that’s used for pimping out vehicles in Detroit, and chose the one that we thought was both the most culturally appropriate and futuristic.

Of course, all this work is contingent on a feedback loop. When we designed the Mothership, we consulted musicians from Parliament Funkadelic to see if they liked the tone of gold.

There’s a rigorous research process into shape, form, scale, sensibility, and vibe. When we get something right, it suddenly goes from being a temporary intervention to something that has greater longevity. We thought the Mothership would be in place for six to eight months, and it transformed a garage into a cultural venue for four years.

Interview condensed and edited.

Explore

Connective spaces and social capital in Medellín

Jeff Geisinger investigates the built environment's impact on social capital in Colombia's second-largest city.

Interview: SITU Studio

The Brooklyn firm combines design, fabrication, and research to explore a broad range of spatial issues.

Re-reading ornament: Textures in Islamic Spain

Fiyel Levent describes an art and architecture of tolerance from medieval Andalusia.