Everything We Can

Low Design Office seeks opportunities to intervene in complex global systems.

May 17, 2021

More than 1,000 young people from West Africa, Europe, and the United States helped co-design the AMP spacecraft, an open-source modular building kit to support grassroots repair, recycling, and maker communities. Credit: Julien Lanoo

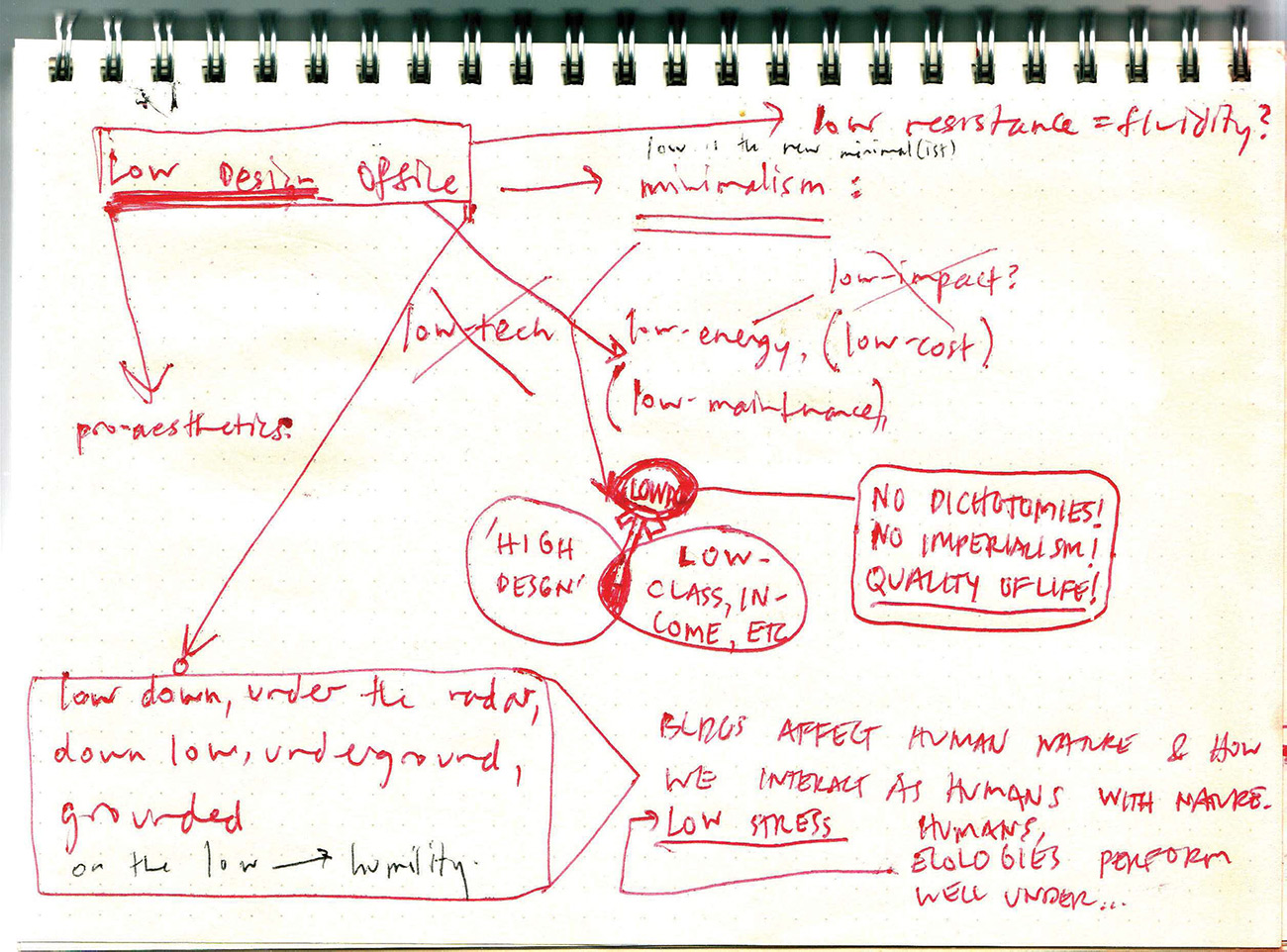

While still in graduate school, Ryan Bollom and DK Osseo-Asare pledged to create a studio that would actively oppose exploitation, which they defined as encompassing everything from environmental destruction to unpaid design labor. In the decade and a half since, their firm Low Design Office, or LowDO, has taken on a wide range of projects, from single-family homes in Texas to participatory design initiatives in Ghana. While these efforts may seem to have little in common, LowDO views them all as part of a larger project aimed at addressing contemporary global challenges.

The League’s Sarah Wesseler spoke to Bollom, who is based in Austin, and Osseo-Asare, who divides his time between Tema, Ghana, and State College, Pennsylvania, about their work.

*

Can you give me a general overview of how you work together? How do you collaborate from different parts of the world and on different kinds of projects?

DK Osseo-Asare: I don’t think I realized the extent to which what we’re doing is different until recently. Even as we try and explain it to people, it simply reinforces how it’s weird.

A few years ago I was at RISD for a symposium, and one of the speakers, Dr. Ben-Eli, talked about this really amazing project dealing with rehabilitating the landscape. After the lecture I asked him, “How on earth do you explain this incredibly complicated project that’s lasted over 20 years with all these different stakeholders and levels of complexity?” And he looked at me and was like, “Well, the reality is you don’t have to explain everything about it to everyone. Everyone only has to understand it at the level they need to in order to be involved.”

I thought that was such a profound answer, because I thought he was going to give me a magical solution—but he was just like, “They don’t need to know everything.”

I mention that because I think it gets at one of the ways that Ryan and I are in sync. We recognize that the world is hugely complex and that there are a lot of high-level systemic, structural issues that are pervasive and diffuse and intangible. We want to somehow change these systems we can’t touch, so our strategy is to basically do everything we can instead of saying, “I have to wait for the perfect thing that’s going to magically make the world better.” But we link these standalone activities to a kind of meta-project.

In trying to intervene in massive structural issues—climate change, neocolonialism, etc.—how do you think about avoiding pitfalls? What’s the process of deciding how you can make a meaningful change?

Ryan Bollom: The key thing for us is we’re not trying to avoid pitfalls. We know that the pitfalls will happen. But if you’re going to address this stuff, there isn’t a blueprint. If we’re not pushing the limit, then we’re not really figuring out how these things work, or how we can make change. It’s all an experiment.

Osseo-Asare: For example, the new town project: In the US context it’s kind of crazy to up and build a new town. But in Africa, the rate and scale of the growth is unprecedented, so you just have people building and making and doing things. So if somebody is going to build something anyway, the more you can amplify the power of design in such processes, it’s hard to say it’s bad.

Bollom: I think this goes back to our background—we both trained as engineers in undergrad. We do a lot of things through the scientific method: make a hypothesis, then test that hypothesis. That’s how the rest of the world works; why can’t architecture start to engage that process in a more direct manner?

How do you decide which projects to take on? And when you’re working on something, how do you determine who does what and at what points?

Osseo-Asare: This is still really strange to me, but I realize that usually people do a project because someone pays them money to do it. But that’s a really weird way to think about your life: “I’m just gonna sit here until someone comes and asks me to do something, and then I’m going to do it, because they give me money.”

But if someone is willing to give you money to work on a project that’s in alignment with something you’re already interested in, everybody wins. And the insights that come about through that process are not embodied only in that particular project—you’re generating information around designing architecture that can live beyond that project.

LowDO's Guadalupe River House, located in New Braunfels, Texas, was designed to accommodate high-level flash flooding while minimizing construction costs. Credit: Casey Dunn

Bollom: It’s not like we’ve completely transcended the normal workflow process of a client coming to us, though—that is a big part of what we do. We’ve been really lucky that on some of the first houses we did in the US, we had clients who aligned with our vision, so we were able to build a portfolio pursuing the ideas we wanted to work with.

But we also try to create projects for ourselves. DK has found spaces that need to be researched or addressed in some way, then created an avenue to work in those spaces, collaborating with foundations or communities. And because he’s been able to do that work in Africa, we’ve been able to skip the normal growth curve for an architect in the US, where you’re doing small-scale residential for a long time, and then you eventually work up to larger-scale projects and different typologies.

Osseo-Asare: In terms of who does what . . . When we started our practice, we wanted to categorically say no to exploitation, in the sense of environmentally extractive industries and neocolonialism and just the attitudes we felt were so pervasive with architecture—especially at a time when it was par for the course for starchitects to not pay their interns.

Saying no to exploitation also extends to our own process: How can we collaborate in a way that doesn’t exploit either of us, or the people that we collaborate with, or who work for us? For a given project or topic, who has not only the expertise, but also the interest?

Bollom: One of the reasons why we do what we do is that DK is Ghanaian–American and I’m from Texas. We’re both interested in the same issues, but we come from different places. We really believe in context, and that if you’re going to try and make these types of changes, you need to understand a place. We don’t want to impose our will on other people.

So basically, whoever has the knowledge base will lead that project. That’s why DK has led most of the projects in Africa and I’ve led most projects here. But we’re always trying to collaborate and complement each other.

Osseo-Asare: Working remotely is new for so many people with this Covid pandemic, but that’s what we’ve always done. Basically, I wake up and turn into a robot; I’m connected to all these computers and screens. We were using Google Wave when it was in beta.

Your projects obviously vary greatly in terms of geography, scale, client type, and a variety of other factors. Do you find that they still inform one another directly in spite of this? Are any of the insights transferable?

Bollom: Part of what we’ve realized overall in our work, but particularly from DK’s projects in Africa, is that it’s all about adaptability, flexibility, responding to different climates and contexts.

Tectonically speaking, I used to think in terms of solid/void—just naturally, not really thinking about it. But more and more, it’s about redundancy and layering. Even with the houses, they have to adapt to so many things: climate, users, the sun, the wind. In cities like Austin or Seattle, where there’s rapid growth and limited economic mobility, how do you create mobility within the architecture so that it can accommodate users as their lives change? And as we deal with the global climate crisis, how do we respond to that?

Osseo-Asare: The idea of layering is very apparent in research we’ve done around urban planning in Africa. The models used to design new towns globally in the postwar period, including in Africa, are based on last century’s functional zoning: you have a rich neighborhood, a poor neighborhood, heavy industry, light industry, commercial. But the ways in which African citizens are actually living in these cities is radically transgressive. If somebody owns a house, they see it as their right to do whatever they want in that property, so they might start a school, they might start a bakery. They might have a bar in their front yard.

So layering is an increasingly legible connection between our projects. And the ways in which you produce the layering are sort of generalizable. Once you have a particular logic for screening or shading or modulating airflow, you can apply it in different ways. Some of the work in Ghana is about employing these ideas in extremely cost-optimized ways, and in the US, it may be more about finding ways to achieve them using products from a big-box home improvement store. But that is definitely in conversation.

How do you see your practice evolving in the future?

Osseo-Asare: I think probably we’ll either continue along the same lines—a hybrid project, ever evolving—or take another step and marshal the resources to put in a broader infrastructure that can facilitate more collaboration, essentially. We have to work with more people in slightly different ways.

In order to pull that off, in my view, it all comes down to technology. The more we can automate certain parts of the process and let machines do it, and then leave us to do what human beings do, I think that’s what’s going to help us bring our project into the next decade.

Increasingly, I think on some level we’re compromising by talking about some things as research and some things as design and some things as design/build. Going back to what Dr. Ben-Eli said, I think people want labels so they can somehow understand it. But I was always struck by how my mentor, Alero Olympio, built everything she designed, more or less. What I learned from Alero is that if an architect only does design work, they can only be paid for their design work. But if an architect is also building, they’re able to earn revenue from design and also construction.

This is important, because in the future automation is going to replace a lot of design and construction activities. So if architects are focused on delivering the same kind of services that they have in the past, which machines can do faster and better and cheaper, they’re self-firing themselves as a profession, in a way. And that’s very brutal to say—but I think that if the commons can share design content to more people, then architects can participate as builders, and that can be part of the future.

Interview edited and condensed.

Explore

Anna Heringer: Sustainability=Beauty

The German architect speaks about her love of mud as a building material.

City as border zone

Architects Ersela Kripa and Stephen Mueller, founders of El Paso firm AGENCY, discuss the reality and rhetoric of the US–Mexico border.

Perspectives on climate change: Economic growth

To what extent is economic growth necessary, and can it be sustained indefinitely?