Retaining Walls

A design commission in a ghost town turned tourist destination allowed Departamento del Distrito to explore ideas about historic preservation.

League Prize winners Nathan Friedman and Francisco Quiñones have long been interested in the complexities of historic preservation. So when their firm, Departamento del Distrito, was invited to design short-term rental apartments in a nineteenth-century silver-mining town in northern Mexico, they saw it as an opportunity to engage with the layers of material and meaning embedded in the site. Building on the ruins that punctuate the local landscape, the project opened a conversation about the community’s boom-and-bust history and its long experience of global exchange.

The League’s Rafi Lehmann spoke with Friedman and Quiñones about the project.

*

We’re going to focus today’s conversation on your Casa Georgina project. Could you introduce us to the project site?

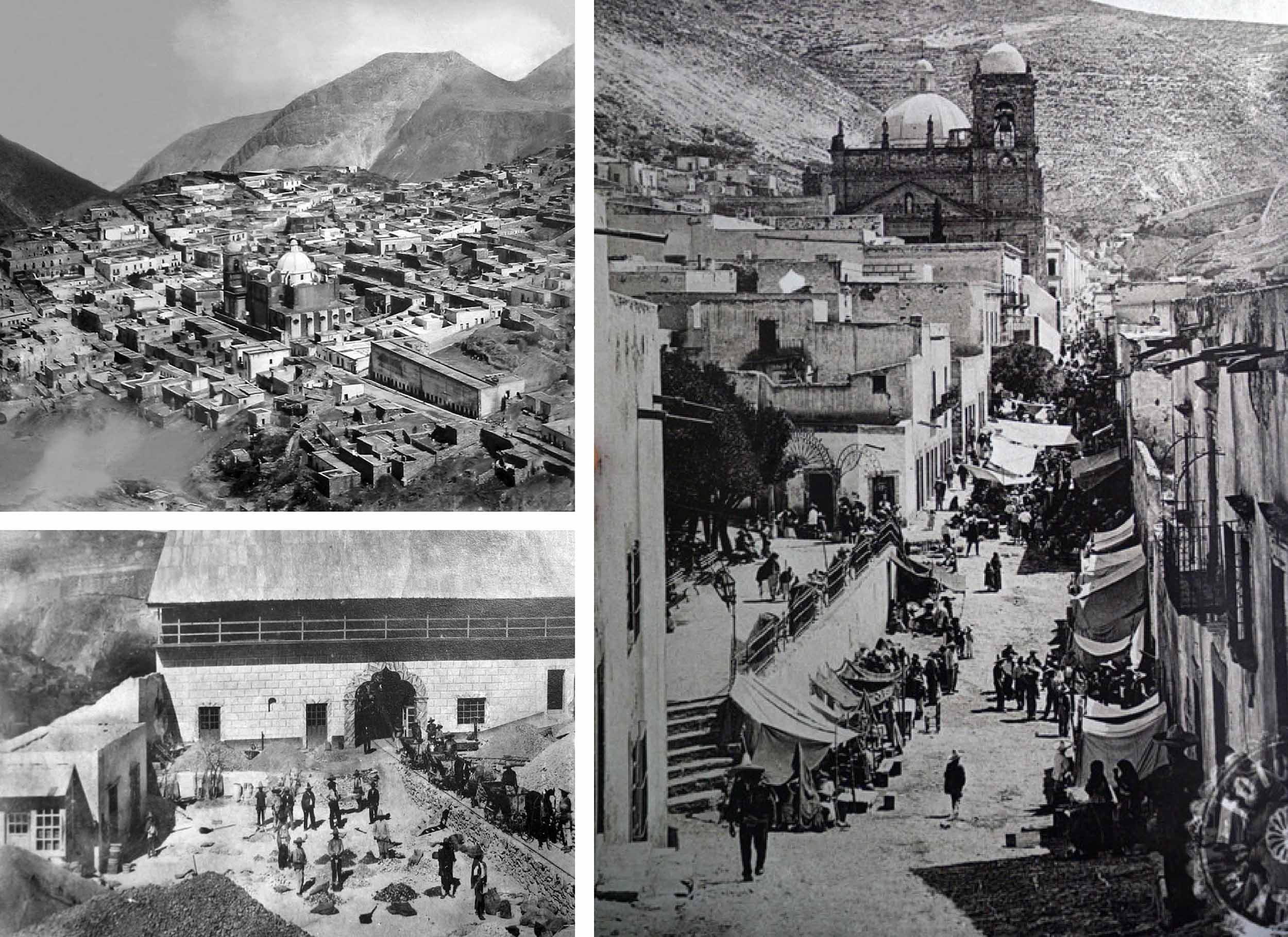

Nathan Friedman: Of course. The project is in a small town, Real de Catorce, in the northern Mexican state of San Luis Potosí. It’s an extremely remote area about 9,000 feet above sea level in the Sierra Madre Oriental mountain range.

Francisco Quiñones: When we were first invited to see the site, it was basically an expedition—it was amazing, really magical. It’s an eight-hour drive from Mexico City. For the last part of the trip you take a 17-mile cobblestone road through the desert, and then you enter a tunnel that cuts through a mountain. The tunnel was used to access a former silver mine, and there’s only one lane; people who are exiting the town need to wait for you to drive through before they can enter. At the end of this tunnel, you arrive at a plateau in the middle of the desert. And the first thing you see—because it’s basically what the town is still composed of—is stone walls, ruinous walls.

The valley itself is a sacred site for the local indigenous population, the Huichol peoples. So this area has been continuously inhabited for a long time. But the town rose to prominence in the mid to late 1700s when silver was discovered there, and it ended up being one of the largest, most prominent silver mines within New Spain.

The mid-eighteenth century was an interesting moment in Mexico. The Mexican War of Independence [1810–1821] was on the horizon, and Spain knew what was coming. They started extracting as many resources as they could, and there was a lot of interest in towns like this one. In this period, you could find European goods in Real de Catorce that you could probably not even find in the capital of the state. We talk about tourism today as though it’s a mid-twentieth century phenomenon, but this locality, even though it’s extremely remote, has been connected globally for hundreds of years.

At its peak, when the mines were all in operation, there are reports that the town had upwards of 40,000 inhabitants. However, after the price of silver plummeted in the early twentieth century and upheavals happened during the Mexican Revolution [1910–20], much of it was abandoned. It became a ghost town. There was nothing to do there in terms of work, so people left and the buildings fell into ruin.

Friedman: More recently, in the past 30 years, it’s become known as a tourist destination.

Quiñones: Right. Real de Catorce is a town that basically lives from tourism now. According to the last national census, it has just over 1,000 fixed inhabitants; the rest is just fluctuating visitors.

In the sixties and seventies, some foreigners, mainly Europeans, visited the town because it had a unique history and was situated within an incredible landscape. Some of them stayed. It was extremely cheap; at that time it was possible to buy an entire structure and rebuild it. Today, many of the local businesses that cater to tourism are owned by Europeans: people from Switzerland, Spain, and Germany.

There’s also domestic tourism. It’s a weekend town for people who live in Monterrey and Saltillo, large industrial cities in the north of Mexico. There’s also a church in the town, the St. Francis church, that is a pilgrimage site. So for part of the year when the St. Francis’s festivities are going on, the town overflows with people to the point that some opt to sleep outside because there aren’t enough hotels.

In 2001, the town was declared a Pueblo Mágico, which is a designation that the federal government created to support and preserve historic towns in Mexico. So by the time we arrived in 2017, the town had already been a tourism destination for a few decades.

Friedman: The town has been reinvented, in a way, to serve and accommodate a contemporary audience. Some people worry that there is now too much development, because even though there are guidelines and bylaws surrounding preservation, it’s still possible to get around them. There are several examples of development within the town that are not sensitive to the context and appear dramatically out of scale.

When we started the project, we were faced with this interesting pinch point of when and how you add to an existing fabric: What do you retain? How does it evolve?

So how did this particular project come about? And who was the client?

Quiñones: Georgina Landa is the mother of a friend of mine. She and her former husband, a French man, visited Real de Catorce and fell in love with the place. They bought land and built a house that was partly made from an old ruin on the property.

The client also owns a small hotel a couple blocks from her house, but at a point she realized that the market was shifting. People are now interested in renting through Airbnb, and that was part of the motivation for our project. We were commissioned to design two small apartments, each containing its own private kitchen and terrace, that could be rented by visitors for longer stays. The project is located within the walled garden of her private home and is, in essence, an expansion of her house.

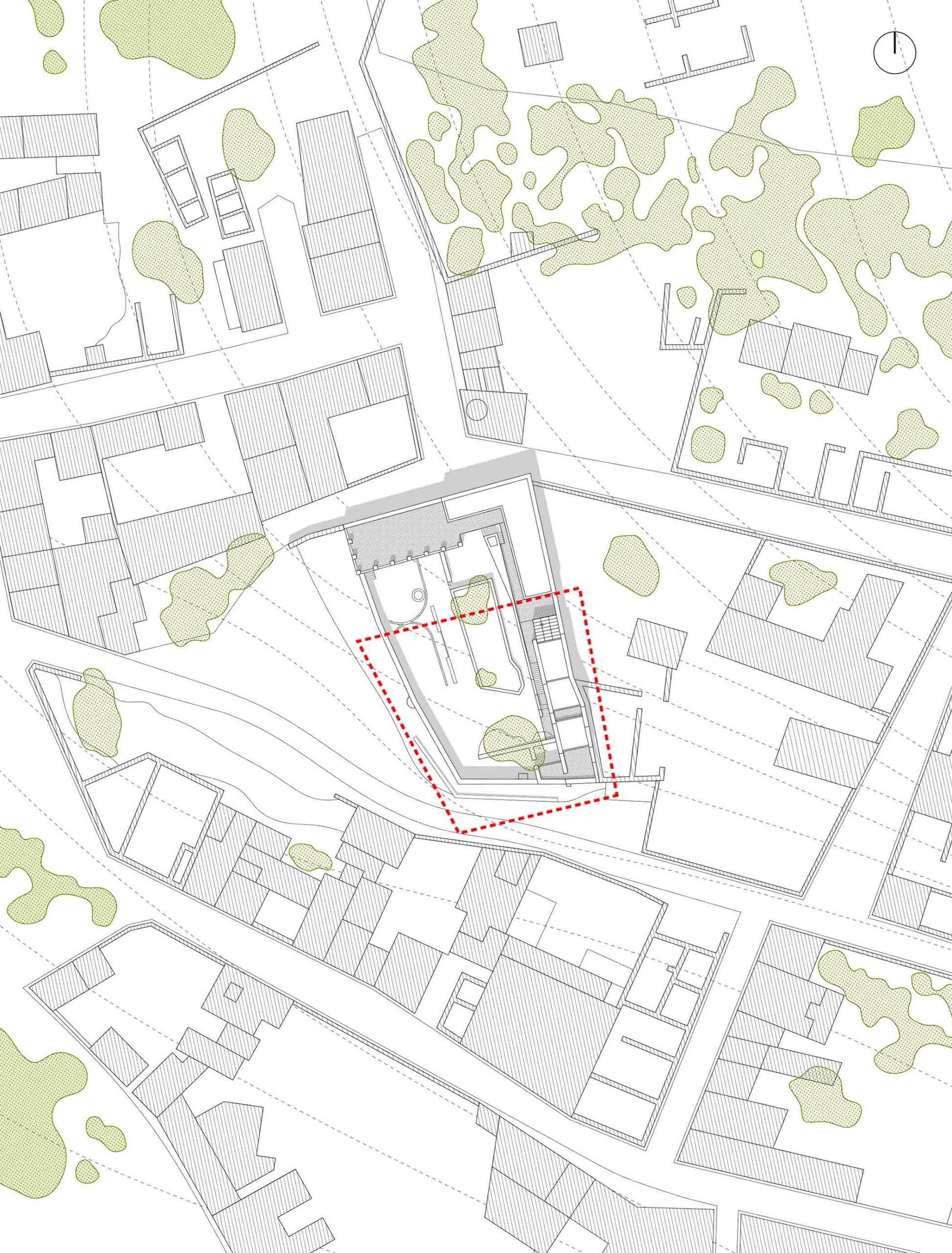

Casa Georgina site plan. The apartments designed by Departamento del Distrito sit within the red dotted line; the client's house is immediately above. Image credit: Departamento del Distrito

Friedman: She has the idea that one day she will move out of the main house and occupy one of the apartments. So we had discussions about how the project might evolve over time.

For us, a clear starting point for the design was to work with the stone walls on site—to study the wall as an architectural element and also as an existing condition, both in the town in general and on Georgina’s lot in particular. There are old stone walls all over Real de Catorce. Many that are still standing were once part of larger structures that have deteriorated over time, shedding their roofs and interior floors that were traditionally structured with wooden beams. And these walls are thick—between 1.5 and three feet thick—and they’re all made out of stone from the local mountain. It’s the typical condition.

The immediate plot of land we were working with was surrounded by one of these common perimeter walls. It included an overgrown garden and existing ruin that was located along the southeast side of the site.

Quiñones: We wanted to play with the idea of the house getting lost in the landscape. When you’re looking at these ruinous walls on the mountain, since they’re made from the same material that they’re sitting on, there’s an interesting play of pixelation and camouflage going on. The first time we went to the town, we hiked through the nearby mountains to view the site at multiple vantage points, and we realized that at certain times of day the ruinous walls seemed to disappear into the landscape.

Friedman: It’s all dependent upon the sunlight, because what allows you to read the wall from a distance is the cast shadow. Otherwise, everything becomes quite flat.

Quiñones: Many of the new structures in Real de Catorce that have been designed by other architects are boxes with crisp lines. And we thought, “What can we do to break the straight line?”

Friedman: Those pure, boxy volumes are the forms that are most legible in the landscape. Even though many of these projects are well-built, from afar you can pick them out easily. For us, that approach was problematic in this context.

Quiñones: So, we broke the continuous line of the wall and created a jagged edge. It’s a pixelation of the volume at large. And because the stones that comprise the exterior walls of the project are small pieces of the mountain, this basic concept is also present in the material—it operates at multiple scales.

Top to bottom: Casa Georgina sections (long), model, and sections (cross). Image credits: Departamento del Distrito

Did you find yourselves turning to the archive at all to understand the site?

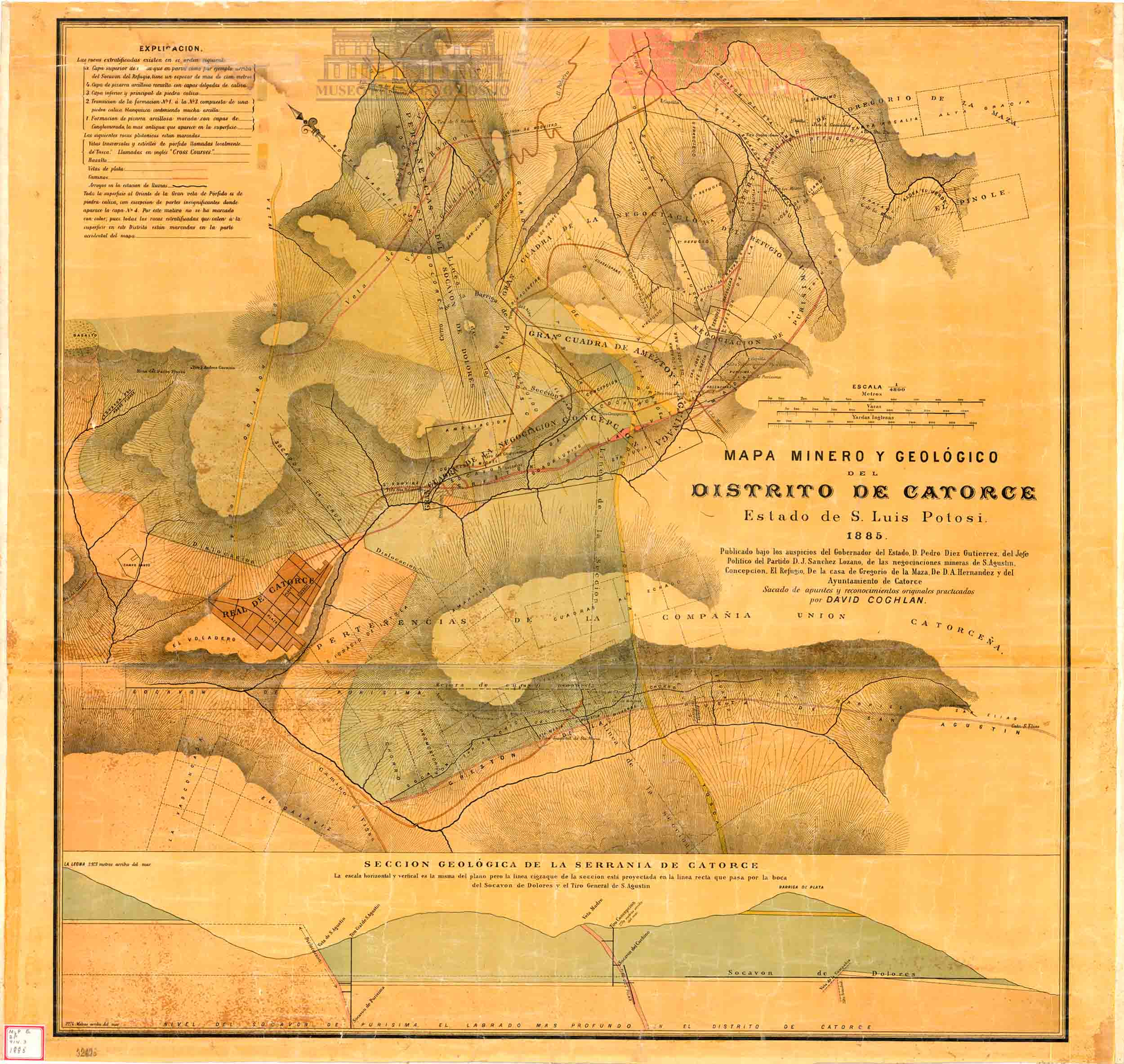

Quiñones: Archives function in a particular way in Mexico. I can say from experience that there is not a culture of archiving here that is comparable to the US, where there are often clear protocols for what is being archived, how material is catalogued, and how to obtain access. In Mexico, there are major archives dedicated to important pre-Hispanic, colonial, and Modern sites. However, for Real de Catorce, a robust historical archive does not exist. Documents are scattered and incomplete.

We’ve been able to find a small collection of maps, photographs, and historical documents through the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia [INAH], El Colegio de San Luis A.C., and a local cultural center in Real de Catorce.

For general research, we also referenced the work of historians and writers who have studied the town, such as Fernando Benítez and Rafael Solana, as well as a more recent study on tourism by Irene Álvarez.

And in the case of the house itself, visiting the archive was literally going to the town and putting the pieces together. Our design process was informed by the immediate architectural ruins on site and concepts surrounding ruination more generally—how these fragments come to be, what they mean culturally for a place like Real de Catorce, and how they might inform a strategy of addition rather than subtraction. We essentially inverted the processes of ruination, while maintaining the defining qualities of the town’s deteriorating stone walls.

For us, this meant a formal strategy of broken or interrupted volumes, blurring the boundary between the architectural project and the surrounding landscape, and exposing latent qualities in vernacular construction methods.

In this way, the project functions as a loudspeaker and reverberates the town’s history. It’s our way to talk about the site’s contemporary state, as well as the historic process through which the site became a ruin.

Friedman: And we were working with a local construction team, led by Rafael Ibarra, that had an immense amount of local knowledge in terms of traditional construction methods and techniques. One unique detail that can be found throughout Real de Catorce, for example, is the way in which small pieces of shale are used to infill the crevices between larger stones in masonry walls. We realized that the most effective way to communicate the design was to literally walk the town with the construction team, selecting certain details that were present in historic structures and discussing how they could be adapted for the project.

Part of the complexity of Casa Georgina is that we embraced the found condition, working with original stone walls on site that were selectively demolished, repaired, and extended to meet the programmatic needs of the client. We had to contend with a kind of collage of construction methods. Some interior spaces in the apartments contain unexpected material protrusions, which are remnants of original stone walls or foundations that have become embedded within a new wall type. And you have to embrace these moments, however strange, because they are part of the identity of the project.

Image credits, clockwise from top left: Adriana Hamui, Departamento del Distrito, Adriana Hamui, Departamento del Distrito

Related to that, I’m curious if you see a relationship between this built project and your practice’s wider interest in preservation?

Quiñones: Our interest in preservation stems from a desire to understand how value is assigned to fragments of the built environment. When specific structures are preserved, who are they maintained for, and what do these choices reveal about a particular culture or society? In that way, our interest in preservation is far more open-ended than a more traditional understanding of the field, in which an authoritative figure decides how a piece of architecture should be maintained, along with its historical narrative.

No piece of architecture is static, and we would like to expand on forms of preservation that are more experimental, in which future conditions are multiple and open to change. This position is supported by research that is ongoing in our office that influences the range of projects we take on, from exhibition and publication work to built commissions. It has helped us to approach a project like En-Medio, which is a free print publication on the legacy of modernism in Mexico City, the same way as an architectural project like Casa Georgina.

Friedman: In Casa Georgina, we tried to translate this interest, this research, through a contemporary design lens without romanticizing the context or even having the structure be read in a particular way. We approached it by playing this game of, “When is the form legible and from what angles, and what views does it produce?”

It really is just working with the site, even though that’s such a cliche to say. But the building is literally built into the side of a mountain. To excavate that rock is such a tremendous process that it was logical to work with the existing sloped condition, with the found wall fragments, and simply build them up.

For an office that is interested in theory and criticism and history, we’re always looking to find those moments where we can expand upon that side of our practice through a built work. Sometimes we’re able to do it, sometimes we’re not. But in a site like Real de Catorce where there is such a deep history and the client was open to working with us, it was an opportunity that we felt very fortunate to have.

Interview edited and condensed.

Explore

The Material and the Immaterial

TO's design for a temporary pavilion in Mexico City speaks to the firm's fascination with material reuse and historical resonance.

Everything old is new again

For Miriam Peterson and Nathan Rich, adaptive reuse projects offer uniquely exciting design challenges.

A Piece of the Ensemble

Palma designed a home for a young boy as part of an ambitious social program focused on a small Mexican city.