City of imagination

By Deborah Gans

In 1987, the League collaborated with the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development to launch a design study on the potential of small-scale infill housing to contribute to the city’s affordable housing needs. The Vacant Lots project culminated in an exhibition and publication, portions of which are republished here on archleague.org.

In the following essay from the 1989 Vacant Lots publication, architect and member of the organizing committee, Deborah Gans contemplates the larger urban visions suggested by the design proposals.

While limited in scope to infill sites, many of the projects for Vacant Lots hold clues to an urban vision. Issues of style and composition alone do not exhaust their meanings. Each project carries in its form the expression of its architect’s imagined city — or city of imagination.

Some projects take their cue from their immediate context. Site 9 in particular generated buildings that almost replicate their neighbors in Jamaica. The frame houses of Marc Litalien and Noah Carter on Site 9 and the designs of James Tice and of Carolyn Krall for Site 10 are examples. Their responses might simply represent an extreme attitude of contextualism, or a kind of micro-regionalism, yet the question arises why this response is so closely linked to the Queens sites of free-standing houses. It seems that the participants accepted these existing types as the appropriate models. The pitched roof and porch carry with them an archetypal idea of dwelling. As in the city of Aldo Rossi, invention is tempered by the discovery of the true and the timeless. The city of imagination is derived from the city of fact and memory.

Anthony Pleskow, Mark Shapiro, Site 6

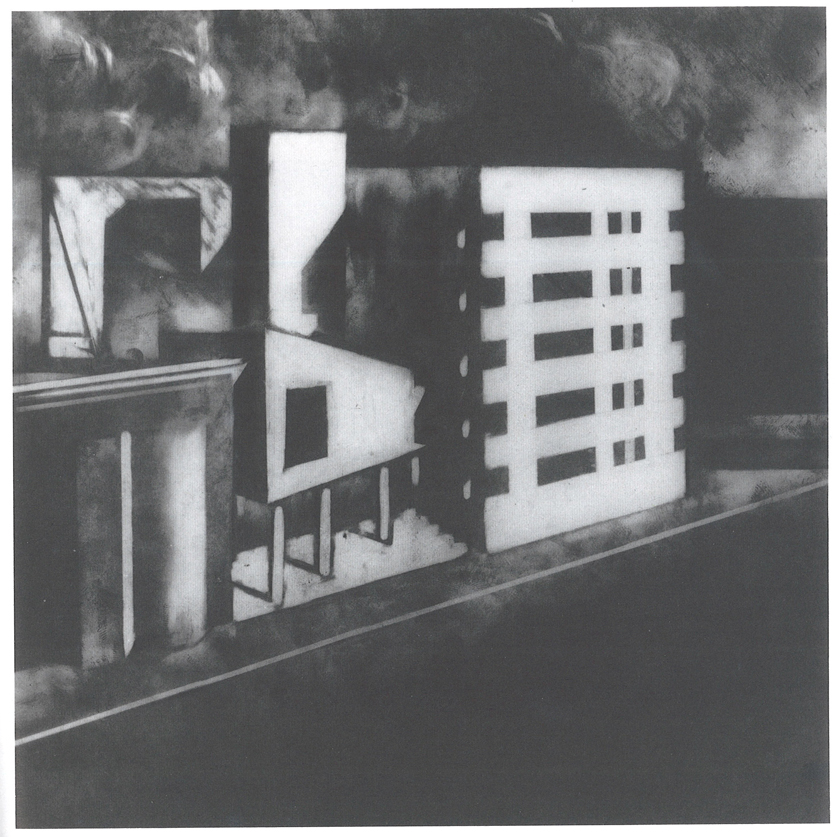

At the other extreme are projects in conscious contrast to their context. One mechanism of this contrast is the language of style. Often the style of modernism, for example, implements values of light, air, and circulation absent from the neighborhood. In other areas, where those values are already present in other guises, modernism becomes rhetorical. It can convey an optimism in man’s ability to solve the intractable problem of dwelling. On Site 6 Anthony Pleskow and Mark Shapiro use a canopy reminiscent of Le Corbusier’s entry at Villa Stein. Changed in scale and in relation to the path of the automobile, this canopy becomes a whimsical flag of the modernist program. In the project of 1100 Architects for Site 9, modernism is identified as functional elements that belong behind the scene. The rear of their house is raised on pilotis creating a covered parking area, while the front resembles its neighbors more both in style and in relation to the street. On Site 7, Tod Williams and Billie Tsien embrace the formula of “tower in the park” but redefine the park as a complex new path through the existing city.

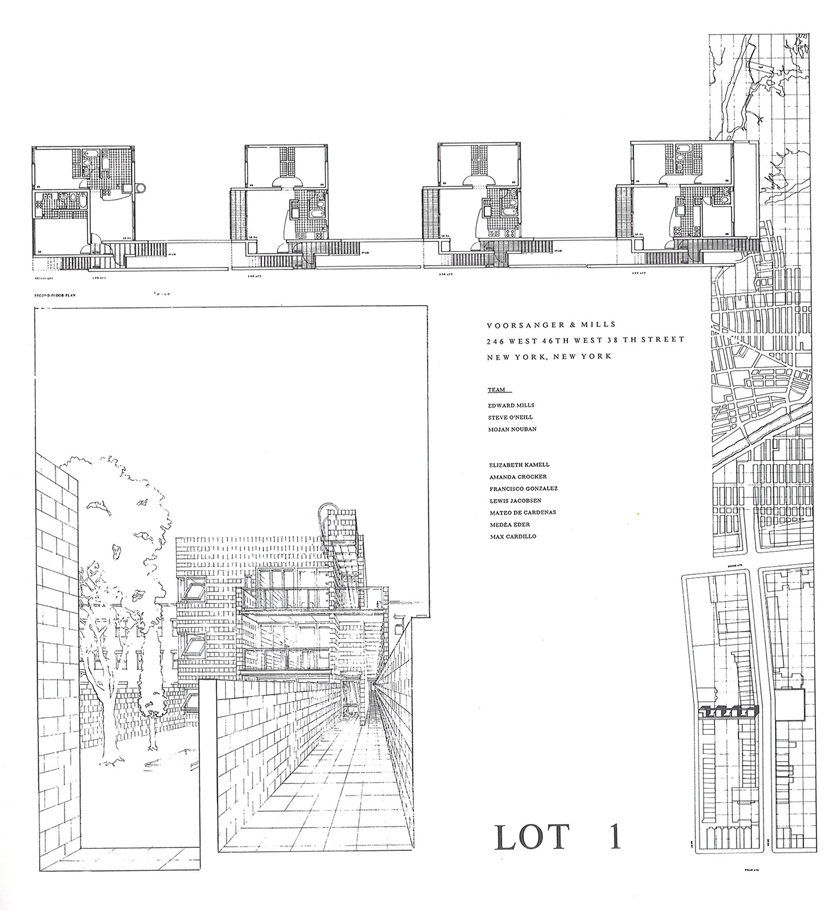

Some projects neither reject nor replicate their context but quietly turn inward in order to focus on an internal composition. Here the long narrow site was instrumental in generating poetic solutions. Sites 1 and 8 border on the existing city for only twenty or so linear feet, while they stretch uninterrupted through the city block. The project of Michael Barratt for Site 8 presents two fronts — one on the street conforming to the established order, the other on the side, suggesting an alternative. The two parts of the Breslin/Mosseri project for a boarding house for Site 8 face each other across an open court which becomes the center of their internal community. In the backyard schemes of Jennifer Sage and the Ed Mills team, both for Site 1, the city becomes a web of secluded places, gardens or courts where the private imagination can run free.

Edward Mills, Voorsanger and Mills Associates, Site 1

Other architects interpret the city as a hallucinatory experience and their projects as episodes in it. On Site 3, Yann Andre Leroy’s house is a billboard backdrop for a murder. On Site 2, in a quieter but still dark rendering, Daniel Rowen and Frank Lupo show us an empty city filled with only chiaroscuro and prismatic volumes in exaggerated perspective like plays on a de Chirico painting.

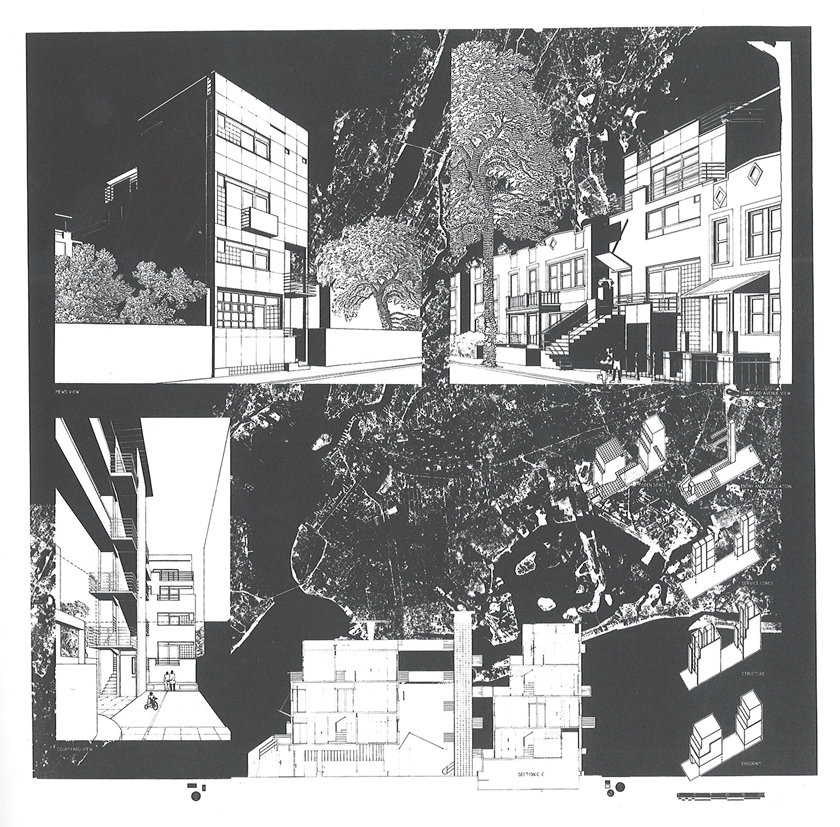

Frank Lupo and Daniel Rowen, Site 2

Most of the architects do not envision their inventions for a single Vacant Lot as the normative solution for the construction of a total city, or even as repeatable. However, imbedded in these objects are ideas of urbanism. Collectively the proposals for Vacant Lots suggest a tension between the will of the architect and the city, between the force of composition and the resistance of a city which cannot simply be composed.