Brownsville, Texas

Challenging the Popular Narrative and Improving Health Outcomes in the Rio Grande Valley

Even before COVID-19, Brownsville was experiencing a public health crisis. We asked Amanda Davé, the program manager at Tu Salud ¡Si Cuenta! (Your Health Matters!), a community-wide campaign run by the UTHealth School of Public Health in Brownsville, to describe what is missing from the standard narrative about health in Brownsville. We wanted to make sure to highlight the work of promotoras (community health workers), who can be found not just in the Valley but in many Latinx communities, and who are vital to addressing the chasms in health equity in Latinx communities. —Lizzie MacWillie, Kelsey Menzel, Jesse Miller, and Josué Ramirez, Brownsville Undercurrents editors

Marcelina Martinez, a promotora with UTHealth School of Public Health in Brownsville, holds the informational health book she uses when visiting participants in their homes. Martinez said, “I specifically work under the health campaign called Tu Salud ¡Si Cuenta!, where I provide health screenings and motivational exercising classes to the community in low-income neighborhoods. I’ve been working here for over 13 years and I enjoy my job because it motivates me to be a more conscious person.” Credit: Veronica Gaona

Prevailing narratives of the Lower Rio Grande region are rife with dismal health statistics and political rhetoric. The news often focuses on disproportionately high rates of obesity and chronic disease compared with the rest of the country, with a third of residents living at or below the poverty line. But these narratives usually do not address the root cause of this disparity: the design of the system as a whole, one that actively isolates a predominantly Hispanic region with Border Patrol checkpoints, suppresses important historical contributions to the formation of the United States, and uses unflattering statistics to blame the neglected rather than those in power.

The popular narrative also fails to mention the importance of the built environment’s contribution to (or detraction from) public health, both in Brownsville and around the globe. According to a study from the World Health Organization, factors like walkability, housing quality, land-use patterns, and prioritization of vehicular traffic over pedestrians account for more than one quarter of the disease burden around the planet, and more than one third of the burden among all children.1Prüss-Üstün, Annette and Carlos F. Corvalán, “Preventing Disease Through Healthy Environments: Towards an Estimate of the Environmental Burden of Disease” (Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2006), pp. 8-16. The lack of infrastructure for physical activity and socioeconomic factors such as higher uninsured and poverty rates disproportionately impact low-income Hispanic communities such as those in South Texas.2Neighbors, Charles J, David X. Marquez, and Bess H. Marcus, “Leisure-time physical activity disparities among Hispanic subgroups in the United States,” Am J Public Health 98, 8 (2008): 1460-4. See source.

For Brownsville and other border communities, 80 percent of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and stroke cases could be prevented by lifestyle modifications such as increasing fruit and vegetable intake and physical activity, according to the International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity.3Marcus, Bess H., Sheri J. Hartman, Britta A. Larsen, Dori Pekmezi, Shira I. Dunsiger, Sarah Linke, Becky Marquez, Kim M. Gans, Beth C. Bock, Andrea S. Mendoza-Vasconez, Madison L. Noble, Carlos Rojas, “Pasos Hacia La Salud: a randomized controlled trial of an internet-delivered physical activity intervention for Latinas,” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 13, 62 (2016): 10.1186/s12966-016-0385-7. Preventing Chronic Disease, an electronic journal from the CDC, reported that Hispanics living on the Texas–Mexico border are significantly less likely to meet physical activity guidelines than other Hispanics in the United States (33.3 percent vs. 44.1 percent).4Fisher-Hoch, Susan P., Kristina P. Vatcheva, Susan T. Laing, M. Monir Hossain, M. Hossein Rahbar, Craig L. Hanis, et al, “Missed Opportunities for Diagnosis and Treatment of Diabetes, Hypertension, and Hypercholesterolemia in a Mexican American Population, Cameron County Hispanic Cohort, 2003–2008,” Preventing Chronic Disease 9,110298 (2012). This is not because South Texans do not want to be active—rather the local infrastructure does not allow them to do so safely. It is hard to go for a walk when there is no sidewalk, or when trails lack shade in the hot, sunny climate.

Designing environments that are more conducive to movement and that reduce reliance on motor vehicles can improve health outcomes by discouraging sedentary behavior. The current public health crisis has forced people to avoid gyms and other indoor venues where they may normally gather to exercise. Decreased physical activity can exacerbate the already high risk of chronic disease in South Texas.5U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition. 2018. Now more than ever, communities and policy makers should prioritize physical activity.

The mainstream narrative also neglects to elevate much of the work addressing these health issues at the local level, where community health workers, known in Spanish as promotores (or, more commonly, promotoras as it is a female-dominated profession), spearhead efforts to improve regional disparities. These local networks and committed community members are the foundation of the health equity work in the region—one that challenges the stigmas created by a bigoted national discourse.

The regional effort to improve public health took a major step 20 years ago, when the UTHealth School of Public Health’s Brownsville Regional Campus (UTH-B) was created to address health disparities specific to South Texas. UTH-B serves as the backbone agency of one of the major regional efforts, the Collaborative Action Board (CAB), which brings stakeholders together from across the Valley to identify ways to improve health at a systems level. One of the goals of CAB is to innovate, implement, and promote science-driven programs, policies, and practices that improve health. Examples include technical assistance around increased physical activity and nutrition policy options for schools, trail development, and transportation policies that encourage active transit alternatives such as bike shares.

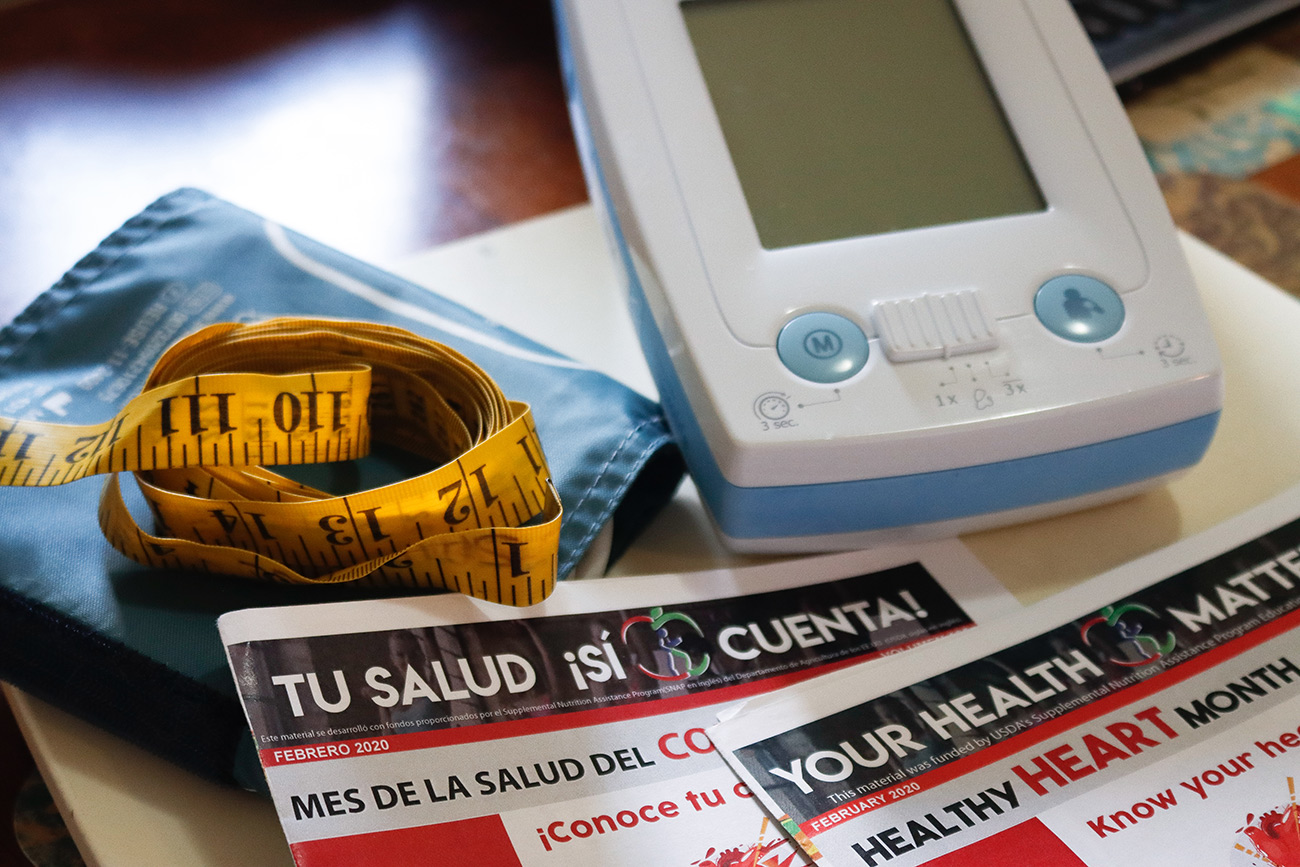

At the local level throughout Cameron and Hidalgo Counties, the Tu Salud ¡Sí Cuenta! (TSSC) campaign at UTH-B works with 11 municipalities and county precincts to focus on the prevention of chronic diseases such as obesity, hypertension, and diabetes with programming that encourages increased fruit and vegetable intake and physical activity. TSSC is culturally tailored to a predominantly Hispanic population, employing local promotoras and certified instructors within each of the partner communities tasked with social support, risk factor screening, exercise groups, and healthy cooking classes. Promotoras are the voices of their communities, acting as liaisons between city officials and residents to advocate for local needs. They are trained to collect information from individuals ranging from demographic factors to primary care information, current levels of physical activity, and fruit and vegetable consumption, and are tasked with following up with these individuals to provide health education and motivational interviewing strategies to increase healthy behaviors. This large-scale initiative has led to positive health outcomes including an increase in the number of participants meeting physical activity guidelines, reduced sedentary behavior, and increased consumption of fruits and vegetables.6Reininger, Belinda M., and Lisa Mitchell-Bennett, MinJae Lee, Rose Z. Gowen, Cristina S. Barroso, Jennifer L. Gay, Mayra Vanessa Saldana. “Tu Salud, ¡Si Cuenta!: Exposure to a community-wide campaign and its associations with physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption among individuals of Mexican descent.” Social Science & Medicine, Volume 143 (2015) : 98-106. See source.

Tu Salud ¡Si Cuenta! participants leave the program after the screening with an understanding of why proper nutrition and regular physical activity are important for a healthy lifestyle. Credit: Veronica Gaona

The COVID-19 pandemic hit the Rio Grande border region hard over the summer of 2020, exposing fundamental flaws in public health preparedness and health equity. Racial and ethnic minority groups are disproportionately burdened with COVID-related illnesses and death. The systemic inequalities mentioned above are partially to blame for this, and communities like Brownsville will continue to be at risk until changes are made.

The health sector must push for more preventive health policies with support from intersectoral partnerships. In addition to reducing disease burden, these efforts will improve quality of life, help retain human capital, and provide opportunities for education and employment. Policy and actions that affect determinants of health often come from outside the health sector, emphasizing the necessity of dialogue, collaboration, and coalition building. Efforts must recognize that national resources, and the equitable distribution of these resources, are vital to address systemic issues that are present in local communities. They must work to change national discourse about these issues in order to bring justice to disproportionately disinvested regions. Health equity solutions are not formulas, but must be tailored and flexible enough to implement hyper-local solutions that are appropriate to each community’s needs, such as the employment of promotoras.

Through these efforts, the region can effectively shift South Texas’ narrative to one deserving of its beauty and resilience.

Biographies

graduated from Trinity University with a BS in neuroscience and international studies in 2008 and received her master’s in public health in 2011 from the UTHealth School of Public Health. Her work has focused on addressing health disparities in vulnerable populations all over the world, encompassing the development of infectious disease programs with The Carter Center in Atlanta and NGOs in Honduras and Peru, prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Malawi, and is now addressing obesity-related chronic diseases in the Rio Grande Valley. A native Houstonian, Davé moved to Brownsville in 2015 to work for UTHealth and has embraced the beauty and intricacies of the Rio Grande Valley. In addition to her professional duties, she is a certified yoga instructor. Davé is dedicated to helping communities thrive in a united effort focused on the health and wellness of each individual that builds a community.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.