In 2001, The Architectural League presented an exhibition entitled Arverne: Housing on the Edge, which featured four proposals for a large section of the Arverne Urban Renewal Area on the Rockaway peninsula in Queens. The proposals—by teams from CASE, City College, Columbia University, and Yale University—were the result of an independent design investigation organized by the League to inform the Request for Proposals issued by the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development for the same site in December of 2000.

On a windy Thursday morning in early March, two weeks after opening for business on the corner of Beach 74th Street and Rockaway Beach Boulevard, the first YMCA on the Rockaway peninsula has a line out the door. Standing at the reception desk, where employees with matching blue T-shirts scramble to answer phones and pass pens back and forth across their computers, two middle-aged retirees in baseball caps are asking about yoga. They live in Neponsit—an affluent district some 70 blocks west of here—and have just returned from vacation in the Florida Keys. Behind them, a trio of elderly Italian men in suede coats flips through pamphlets advertising Zumba classes. “You think this is busy? This is nothing,” notes an administrator stationed by the printer. “We’ve been totally slammed every single day. Today’s actually slow.”

Nearby, Natasha Lynn Tucker waits for a tour of the facilities with a large group of Rockaway residents. Like their ages and ethnicities, their neighborhoods vary. Tucker, an Alabama native, moved to Beach 9th Street in Far Rockaway—the region’s easternmost section—in 2008. She has struggled to find ways to keep her son Robert, who is autistic, active and engaged with other children and has eagerly awaited the Y’s long-heralded opening. “I’ve lived here for six years, and this is the only place like it that I’ve seen,” she says, adding that she is undeterred by the 60 blocks separating it from her home. “Robert’s doctor said he needs to exercise, and I’ve had nowhere to take him other than the park. The waves at this beach are too strong, but the Y has the pool, and that slide, and dance and yoga for kids.”

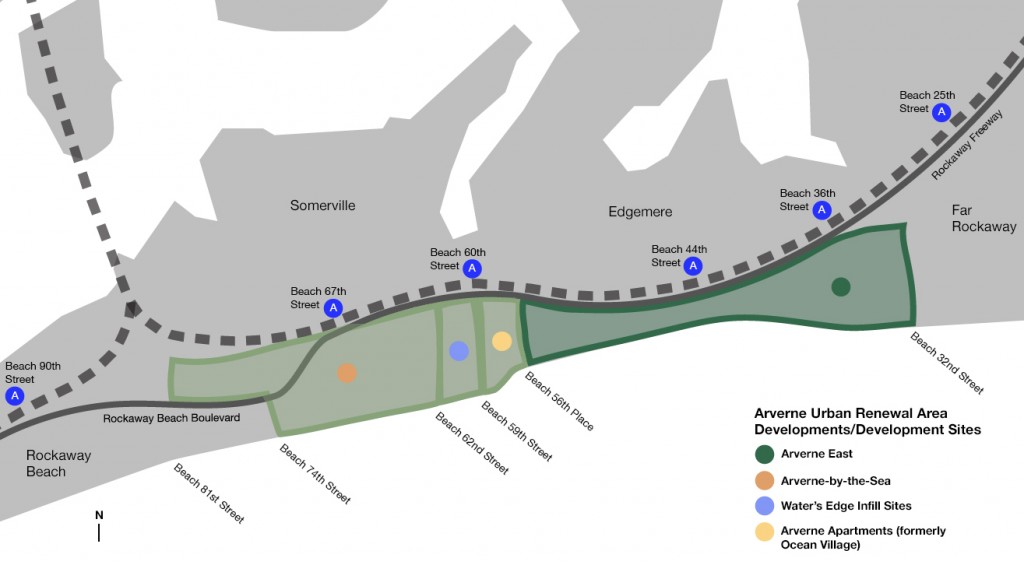

Jamaica Bay, the Rockaway Peninsula, and the Arverne Urban Renewal Area (in blue)

Elevated twelve feet above sea level, the YMCA occupies a full block a mere 380 yards from the beach. Upstairs, cool gray and white walls frame floor-to-ceiling windows oriented toward the ocean, and the ground level hosts the peninsula’s only public indoor pool—the largest aquatic center of any Y in the city—meant in part to address an urgent need for swimming lessons.

The placement of a $23 million, 44,000 square-foot community center at this central point on the Rockaway strip is no accident. It represents a notable phase in the overhaul of a formerly crime-ridden, 308-acre beachfront stretch in the neighborhood of Arverne. Designated a Title I Urban Renewal Area by the City of New York in 1968, the land bounded by Beach 32nd Street, Beach 84th Street, Rockaway Freeway, and the Rockaway Boardwalk was bulldozed to accommodate new low-income housing projects that never materialized. As funding dried up and development stalled, the area sat empty for decades—an urban stain left behind by bureaucratic blunders and financial complications, culminating in the fiscal crisis of 1975.

Even when considered within the rocky history of the peninsula at large, Arverne has faced particular challenges, remaining stagnant and vacant while nearby neighborhoods evolved. Numerous strategies to develop the site, which is owned by the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD), have been discussed since the ’70s. Initially, locals pushed for the construction of resorts or amusement parks in hope of returning the Rockaways to its former glory, but a series of community charrettes dispensed with the idea of a casino or a nine-hole golf course. Six Flags flatly turned down an invitation to build, and a controversial proposal by Forest City Ratner to fill the expanse with 12,000 units of dense, high-rise housing never came to fruition.

The Arverne Urban Renewal Area and surrounding neighborhoods | Click to enlarge

Water’s Edge

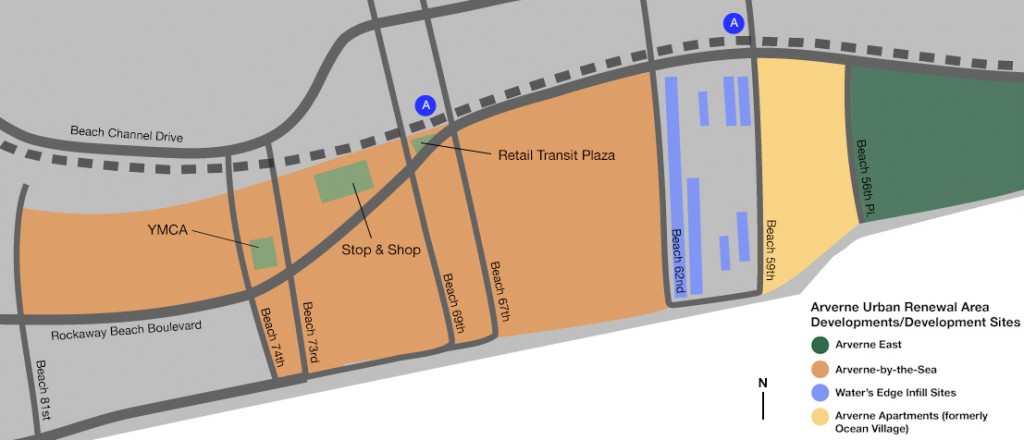

In 2000, HPD partnered with the consulting firm HR&A to study alternatives for the area. The program they settled on broke the acreage up into three chunks, and Requests for Proposals (RFPs) were issued for each, specifying mixed-use plans that would integrate residential sectors with retail and recreation. Decisions were sped along by the September 11th attacks, which claimed the lives of 400 local residents (the peninsula has always housed an abundance of civil servants, especially police officers, firefighters and other first responders) and the subsequent crash of American Airlines Flight 587 in Belle Harbor. Within one year of the RFP’s issue, Water’s Edge was brought to life: the first new housing built in Arverne in over 25 years.

Overseen by Vincent Riso and his Briarwood Organization, the affordable development was conceived for two infill sites between Beach 59th Street and Beach 62nd Street. In exchange for the subsidized sale of the land by HPD, Briarwood passed on cost savings to buyers. The first 40 homes, offered initially via lottery to Rockaway residents, were marketed at 60-120% of the Area Median Income along with a homebuyer tax credit and a $4,000 allowance. These units sold quickly. The 130 condominiums that made up the development’s second phase—financed in large part by a $24.7 million construction loan from the loan companies no credit check were not completed until 2009. The crash of the housing market caused price differences between below-market and market-rate homes to narrow and interrupted Briarwood’s efforts to find buyers. $2.8 million in New York State Affordable Housing Corporation funds allowed them to provide up to seven-months’ free maintenance on some units. Today, two condos have yet to be purchased and have never been occupied.

Click to enlarge

Arverne-by-the-Sea

A year after Briarwood began work on Water’s Edge, HPD designated a joint venture between the Beechwood Organization and the Benjamin Companies as the developer of a 19-block stretch directly to the west. Sited between Beach 62nd and Beach 81st Streets, the $350 million, mixed-use Arverne-by-the-Sea broke ground in 2002. Beechwood/Benjamin aimed to attract middle-income buyers for their market-rate housing, a population who often passed over the historically disinvested region as a viable place to invest in a home. A 20-year tax abatement proved an attractive perk, and the developers anchored the 2,300 residential units around two-family homes, which allows owners to subsidize their mortgage with rent brought in from a tenant. Two of the development’s six sections are made up entirely of mid-rise condos, one of which will be the last section to be completed in the coming years. Units in the first four sections to come online are sold out and fully occupied.

Added to the housing mix are a charter school for up to 800 K-8 students (still in the works), the YMCA, and some 300,000 square feet of retail space. Crucially, this space includes a 50,000 square-foot supermarket, a basic necessity of which the Rockaways’ 120,000 residents have shockingly few. Stop & Shop opened in 2010 and continues to serve as the most accessible supermarket in the eastern half of the peninsula: it miraculously reopened a mere three days after Hurricane Sandy’s landfall, and it remained the only operating grocery store in the Rockaways for six months. (The Key Foods locations on Beach 88th Street and Beach 105th Street were both shuttered by the squall, and they have yet to reopen.)

A construction site in Arverne-by-the-Sea in 2010 | photo: Nathan Kensinger

“Historically in the Rockaways,” says Gerard Romski, the project executive for Arverne-by-the-Sea, “you had the eastern portion and the western portion; very high-priced homes in Belle Harbor and Neponsit and some significant economic detriment on the eastern part. Arverne-by-the-Sea is really the bridge between the two.”

Seen from afar, Arverne-by-the-Sea materializes out of its surroundings like an oasis of quaint, suburban, beachside housing. Connected by a network of curving streets that frame plots of communal landscaping, the homes have modern silhouettes, ample windows, beachy blue doors, and rooftop terraces that look toward the sea. Private backyard patios adjoin shared expanses of green that are accessible through low picket fences. Its placement is both fortuitous and strategic, and, like the Stop & Shop, it was left virtually unscathed by Sandy even while proximate neighborhoods were demolished by fire, wind, and water.

“It was like we were in a safe little bubble here,” reflects John Ruscilo, a Flushing, Queens, native who purchased a two-family home in Arverne-by-the-Sea with his partner in 2011. “The homes are well constructed, and the guy who built them here built them in Florida first—so they have definitely been hurricane-tested.”

Arverne-by-the-Sea in 2010 | photo: Rocco S. Cetera

Natural forces also serve Arverne-by-the-Sea. It sits behind one of the peninsula’s broadest stretches of beach, which is buffered by rock jetties that extend into the sea, accumulate sand, and break up the power of waves. A landscape of naturally occurring dunes covered in salt-resistant scrub brush with strong, deep roots acts as another impediment, and then there is the Rockaway’s renowned Boardwalk, built from thick planks of Brazilian Ipe wood. Elsewhere along the coast, sections of the structure were lifted clean off of their anchors and blown through the windows of nearby homes. Fortunately, in front of Arverne-by-the-Sea, the platform was only displaced slightly from its mooring, serving as intended as a bulwark against the surge.

Some have denounced Arverne-by-the-Sea as an enclave of luxury in an otherwise compromised socio-economic landscape. When the RFP was issued in 2000, 28% of Rockaway residents were living on some form of public assistance, and although the city required Beechwood/Benjamin to offer the homes to locals first, the development has attracted a diverse population of middle-income buyers from other parts of Queens, Brooklyn, the Bronx, and western Long Island.

This is intentional, according to Jonathan Gaska, who has served as district manager of Community Board 14 for 25 years. Gaska notes the desire, shared by both the developers and the community board, to “bring in people with disposable income” who would ideally help advocate for community issues and drive commercial development. “Overall, the Arverne area has increased in value,” reflects Briarwood’s Vincent Riso. “We at Water’s Edge are proud to have been a part of that. And, of course, being located across from a market-rate development is a big boon to the purchaser of our more affordable housing.”

Arverne View (formerly Ocean Village) in 2014 | photo: Jonathan Tarleton

Ocean Village/Arverne View

Similarly affected by the region’s changing local economy is Ocean Village, a formerly dilapidated Mitchell-Lama cooperative three blocks east of Arverne-by-the-Sea. Built between 1972 and 1974 during the slum clearance program overseen by Robert Moses, the soaring concrete structures had fallen prey to crime and drugs by the mid-80s, and were soon among the most dangerous areas on the peninsula. Negligent landlords accumulated debt and failed to maintain the buildings; many apartments, illuminated by dim overhead lights, were choked by layers of black mold; and appliances hadn’t been replaced in decades. After Sandy made landfall, residents lived for weeks without running water, plumbing, heat, or electricity, navigating pitch-black stairwells polluted by sewage.

In November of 2012, with 350 units abandoned, Ocean Village was purchased for $60 million by L+M Partners—one of three developers, along with the Bluestone Organization and Triangle Equities, designated by HPD to develop nearby Arverne East, the third chunk of the urban renewal area. The future of its still-barren 81 acres is uncertain, but it was recently the subject of an international design competition. There is no doubt that an improved Ocean Village would only enhance the value of L+M’s larger project.

“People are really looking for a community place—for something to bring them together.”

Working with State, City, and Federal agencies, L+M agreed to continue operating Ocean Village as a Mitchell-Lama development, maintaining its project-based Section 8 contract, providing rental subsidies for about 10% of its units, and offering vouchers to existing tenants so that their rents did not increase. They then undertook a comprehensive rebranding and redevelopment process, changing the complex’s name to Arverne View, elevating its electrical wiring systems to protect against storm surges, installing backup generators on several roofs, and rehabbing all 1,093 units (often doing so while they were still occupied). New kitchens and bathrooms were standard, as were new floors and fresh coats of paint. First priority for vacant units was given to Rockaway locals displaced by the storm; although rehabbed units were priced somewhat higher than in the past, they still qualified as affordable housing. The bulk of the work was completed by fall of 2013, and the complex soon reached 100% occupancy for the first time in decades.

Today, the Arverne View buildings have clean white exteriors offset by modern, geometric blocks of slate gray and yellow. Previously bleak courtyards are lit by outdoor lamps installed on freshly seeded lawns, and the crumbling planters that had been left to wither have been replaced with lush, salt-resistant shrubs. The development also features over 15,000 square feet of elevated commercial space that will be used as an industrial kitchen and a food incubator, which can hopefully serve the peninsula in future storm relief efforts.

Considering the years of stagnancy following the creation of the urban renewal area in 1968, the change in Arverne since 2000 is striking. “If you look at what [Arverne] looked like here before and what it looks like now,” reflects Jonathan Gaska, “I think most people would argue that certainly, from a development standpoint, it looks much better. The old joke in Rockaway was, ‘A traffic jam is one car in front of you at red light.’ Now there’s three cars in front of you because of all the development, but I think most people will trade significant added value to your home, and a less crowded classroom—because they’re going to build a new school—for waiting one more cycle at the traffic light.”

Besides, the effects of new or rehabilitated housing, infrastructure, and facilities may reverberate. Back at the YMCA, Tucker and her son have completed the tour and are discussing membership options at the front desk. “I don’t think it matters where you live,” she says. “It might be a little bit far for us, but after Sandy, people are really looking for a community place—for something to bring them together.”

Emily Nathan is a culture writer and editor based in Brooklyn, New York.

The views expressed here are those of the author only and do not represent the position of The Architectural League of New York.

Explore

James Wescoat: Climate, energy, and water-conserving design

Landscape architect James Wescoat discusses water supply and other hydroclimatological conditions in major American cities.

Re-envisioning New York’s branch libraries

The Center for an Urban Future's latest policy report provides a comprehensive blueprint for bringing these vital community institutions into the 21st century.

Water

In nearly all American cities, clean drinking water is available with the turn of the tap. Behind the spigot, however, is an energy-intensive system of legacy infrastructure governed by layers of policy and administration.