All Together Now

Through its collective model and emphasis on discussion and debate, Citygroup seeks to move beyond business-as-usual design.

June 14, 2022

Citygroup has been actively involved in a number of initiatives designed to increase affordable housing and prevent displacement in Chinatown and the Lower East Side. Here, several of its members present a proposed rezoning plan during a walking tour organized by the Chinatown Working Group, a coalition of local organizations working to strengthen the community. Image credits: Photo by Citygroup; image on banner by soft-firm

For the founders of New York’s Citygroup, a desire to escape the constraints of business-as-usual design jobs led to the formation of a collective dedicated to understanding the current state of architectural practice and experimenting with alternative models. Over the last few years, the group has produced a wide range of exhibitions, events, collaborations, and installations, often working from its Lower East Side storefront space.

The League’s Alicia Botero spoke with a several members of the group about their organizational structure and their approach to design. In keeping with Citygroup’s emphasis on the collective, interviewees asked to be identified only by their first names.

*

Can you tell us about how Citygroup’s structure came about? Why did it feel important to create this collaborative practice at this moment in time?

Violette: In 2018, when we started Citygroup, we were all craving the opportunity to do projects together after four or so years out of graduate school, where many of us got to know one another. So there was always the idea for a group, and to use the shared energy that we would get when in discussion with one another. And rather than having the group be completely social or trivial, we thought it could be grounded in the issues of architecture that we were experiencing every day.

I personally would say that architecture is a social practice, and a very collaborative one. In graduate school we really had that spirit of a cohort, but when we all dispersed and were working in different offices, those really driven efforts we each made as part of a group changed—they became the work that we do every day in our separate offices. We wanted to bring some of that effort back into a thrilling project, like an architectural studio project that you might do in graduate school.

Will: We started getting together as a group that ebbed and flowed in its numbers and had a rotating cast of characters, but that often coalesced around gripes about where people were working and how some of the idealism of academia had been taken over by everyday concerns of conventional offices. One way I think about Citygroup is that it’s trying to transform that whining into complaining: speaking in a way that might actually do something about the issue. We want people to feel like they’re part of a group that collectively can have an impact and resuscitate some of those ideals about architecture that we felt were sliding in our day-to-day work.

Michael: Yeah, and we also felt like it was important to look critically at the profession. We wanted to not just start to do architecture differently, but instead come together, have discussions, talk, analyze how architecture is currently practiced so we could then think about how we might go about things differently.

Do you think there’s anything about this particular moment in time, or this point in architectural history, that makes a collaborative model like this important?

Michael: Well, one way to answer this question is that in a lot of ways, we’re trying to close the door on the moment of thinking about architects as individual white men. The way recognition gets dealt out within the discipline today, focusing on individuals, feels not true to the way architecture’s actually practiced. It’s collaborative and communal in how it gets produced, and also in how we experience it. It feels like we’re way past the moment of starchitecture; this is something we wanted to highlight.

Merica May: To piggyback on that, the way I joined the group was through coming to a debate. What I appreciate about Citygroup is that it’s flexible, humble, and discursive. The discovery comes through just talking through subjects. It’s not a top-down manifesto or some purist solution that we believe is correct, but sort of a tumbling inquiry into the best way to practice.

Michael: I really like that. We’re not problem-solving; in some ways we’re trying to open up questions and be messy and make things complicated.

Merica May: It’s so different from capital-M Modernists where there’s a manifesto and they execute the vision that is didactic and self-determined—they tried to make a better society from what they thought was right. We offer a much more hesitant sort of solution that is slower, maybe, but also very operative in the community sense. It’s not architects dictating, but listening.

Manifesting Manifesto, a 2020 exhibition, asked attendees to interrogate and edit a Citygroup manifesto. The result: “[N]ot an a priori theory but a standpoint that materializes within the friction of the world,” according to the group’s website. Image credit: Citygroup

Will: I would say, though, that it’s not as if this contingent way of looking at social problems is only the means to propose a project or a solution. It is the work. It happens through embeddedness—trying to be people amidst other people rather than imposing things from outside.

So for the debates, we organize them to bring a community of people together who are interested in these issues, but it’s not like, “Okay, so what are the action items from this conversation we’ve had as a group?” The debate is an end in itself.

And that’s how we’ve thought about all these processes or projects. They are part of this larger effort that isn’t about built work or even paper architecture. It’s really about thinking more broadly about community and how we live together.

David: On the question of why this moment in history, it’s also important to say that in the past couple of years, the struggle of vulnerable communities has really become much more part of the collective discourse. The formation of Citygroup didn’t intentionally coincide with that, but I think we’ve all felt awakened to the need to act on behalf of social justice. And in the discipline of design, that’s not always people’s first intention.

Violette: Right. Even a couple of years before the Black Lives Matter protests and all the unrest regarding these really deep social fissures, we realized that, as architects, we were working on a very monotonous strand of projects for a very elite audience, and that this was at odds with the architecture we aspired to create, which is both public and serving a greater public. In the practices where a number of us worked, the public projects were maybe shopping centers or museums, not the subway stations or housing or public open spaces we’re interested in—spaces that everybody has access to, with no conditions. That was something we were trying to subvert, thinking about what would happen if architects worked for a different client.

David: As architects, we can’t always choose our clients, but at Citygroup, we’ve made civic or cultural problems the client, and that has driven a lot of our activities and the way we engage with the community.

Michael: We’re also thinking critically about how we collaborate with communities or participate in activist efforts. We’re not trying to reiterate the conventional approaches to participatory design, which ask communities to enter an arena where there’s an unbalanced power hierarchy between the architect and the community participant. Instead we’re thinking about the reverse, looking at how architects can participate in existing community activist efforts and lend our skills, as people who can make visual things, to those efforts. Instead of just diving in and forcing our architectural ideas on communities, it really starts with a lot of listening—first lending our bodies and voices to what they’re already doing, then starting to think about how we can contribute as architects.

Sebastijan: It’s also not just architects that are in the group. Architecture’s a pretty cloistered profession, and I think a big part of Citygroup’s success, and what makes it interesting, is that there are a number of active members who are not architects in a traditional sense. There’s a pretty diverse crew at the debates, especially; there are creative people, businesspeople. We’ve had philosophers and doctors. And recently, with the Chinatown Working Group activities we’ve been doing, we’ve also been working more with the general public. So the idea of community and who can participate in architecture is broadened.

A local edition of Chinese-language newspaper Sing Tao Daily featured Citygroup's work in support of the Chinatown Working Group Rezoning Plan, which seeks to preserve affordable housing and protect community-based small businesses. Much of Citygroup's work focused on helping laypeople understand highly technical zoning concepts. Image credits: Photograph by Citygroup; axons featured in article produced by Citygroup; visualizations featured in article produced by AJ Artemel, Jennifer Siqueira, and soft-firm

How does Citygroup work together? How do you make decisions and draw people in? Can you describe the nuts and bolts of how you operate?

Merica May: We just had a meeting about that, actually!

Michael: To be honest, it’s something we’re still figuring out. The most difficult part of this work is finding ways to work together; that’s harder, in a lot of ways, than actually doing projects. So it’s an evolving process. We want Citygroup to be a platform, or a tool or mechanism, that people can plug into in order to pursue their ideas, but we also feel there does need to be a structure that allows for everybody to know how to use our space or pursue projects.

Alice: This is a design problem that we’ve only started posing to ourselves. And it’s a knotty one, and one that will change over time. It’s kind of amazing that we’ve managed to tumble along, as Merica May said, for this long without having something more defined. But it has been this magical process, in some ways, whereby interest in a topic bubbles up and then something appears—that’s what it’s felt like to me, at least, in the initiatives that I’ve participated in. I think of it as lots of molecules that cluster in moments of intensity, but that change over time, gathering around whatever centers of gravity might appear.

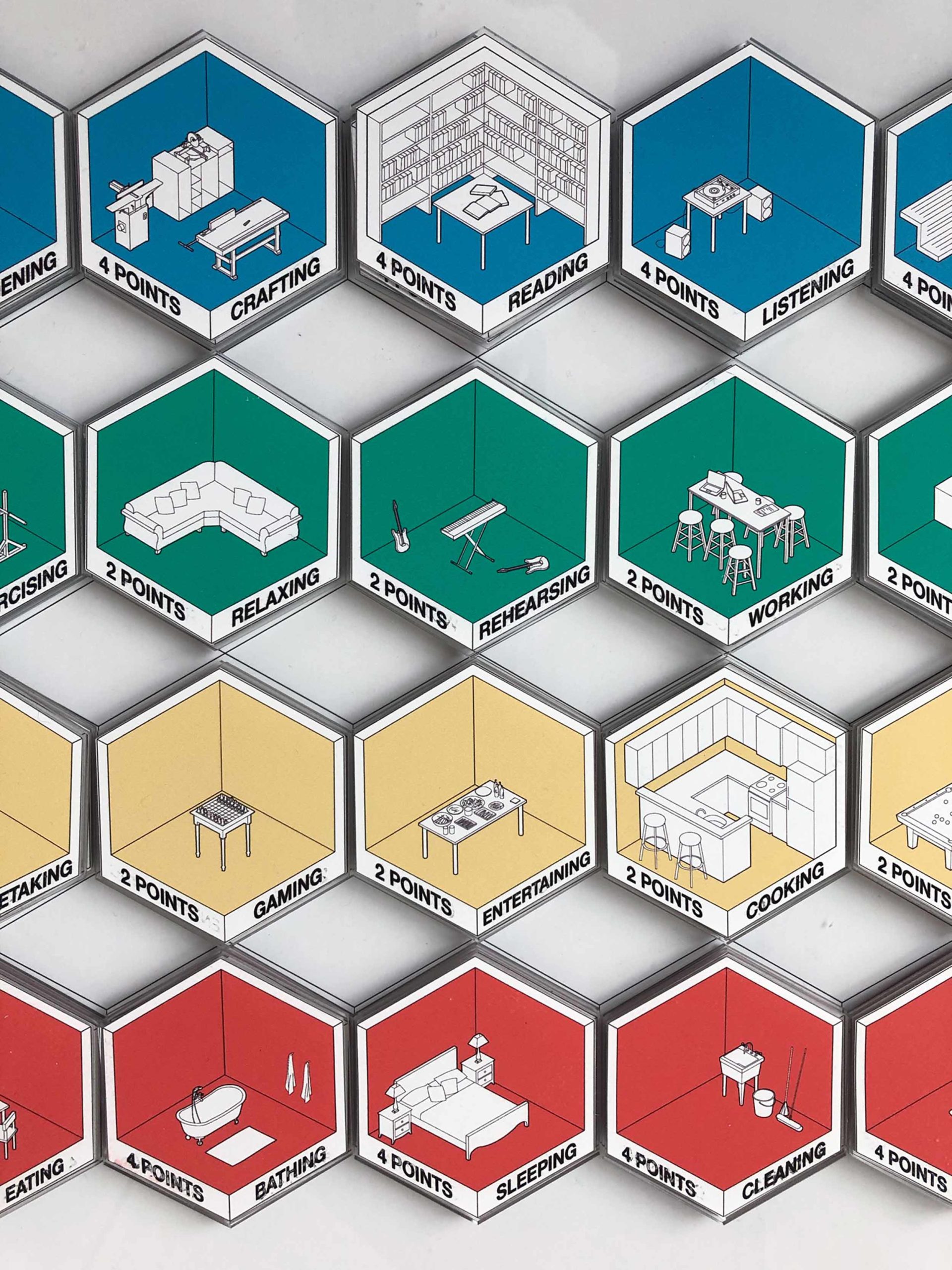

For the 2019 Oslo Architecture Triennale, Citygroup created a board game exploring different configurations of living space, calling into question the formulas typically adopted by real estate developers. Alone Together, The Game serves as a call to imagine diverse dwelling types that respond to different programmatic needs. Image credit: Citygroup

David: Thankfully we don’t get bogged down with bureaucracy. There seems to be a collective spirit towards just getting a project done—that’s the most important thing. And that’s led to a lot of momentum.

Merica May: And whoever participates is a part of the community.

Alice: Yeah, we’ve said that before: Membership is defined by participation.

Violette: Citygroup, to me, has functioned as an open network. It starts with a call to X many people, and then some people will forward it to somebody they know who they think would be interested. So there are all these encounters that build upon one another which allow us to reach a broader audience and recruit more interested parties. There isn’t a formal recruitment process—it’s more like if you show up and you want your work to be in the show, it’s in the show. But we are trying to clarify what steps might be followed so that it’s even more accessible, and also more robust over time.

The Citygroup exhibition Ideas for an affordable 5 WTC presented alternative proposals for 5 WTC, a residential supertall planned for the last undeveloped site in the World Trade Center master plan. The developer's plans call for a quarter of the units in the building to be rented at below market rate to people earning less than half of the area median income—a target a local group called The Coalition for a 100% Affordable 5 WTC says is far too low. The exhibition asked designers to present alternative visions of the project in support of the coalition's goals. The show was organized with The New York Review of Architecture. Image credit: Citygroup

Michael: And the reason why we feel it’s important to cultivate an inclusive, participatory spirit is because a lot of the institutions that relate to architecture in the city feel inaccessible to young architects that are trying to pursue their ideas, or just get their foot in. We think it’s really important to create a group and a support network that architects and people interested in the city or the built environment feel like they can come to and pursue their interests and thoughts and have a discussion. It’s something that doesn’t really exist within New York City, or even within the broader practice or culture of architecture.

Will: If you had asked a couple of years ago, before the pandemic, what are the crucial ingredients that allow for these things to happen, I probably would have put our space at the top of the list. We thought having a space was significant because as architects, that’s what we fundamentally deal with: providing spaces for encounters. To have a space we could call our own that could act as a home base for these projects was very important.

Opening of exhibition featuring anti-displacement artwork created by local artists and documentation of the history of labor struggles in Chinatown. Organized with the Coalition to Protect Chinatown and the Lower East Side. Image credit: Citygroup

And then, of course, in the last two years all those ideas have been challenged. I think we’ve come to realize that it’s actually more about the group. So now we’re figuring out how this open network can function without the center of gravity that is the space—although hopefully we’ll also be able to use the space the way we did before. But the past two years have unlocked the idea of being able to engage with people who are further afield. Before, our focus was really on the neighborhood in which the space is located, which also happens to be where a number of members of Citygroup live and spend their days. So we’re now trying to think about how that sense of embeddedness and connection to a space can start to exist with a larger membership group and a more diffuse constellation of locations where people might be taking part.

Could you tell us a bit more about how you see that duality between embeddedness and diffusion playing out over time?

Violette: To me the space is really important, especially after the pandemic. In New York we’ve seen a lot of people take off and go live elsewhere, so we feel even stronger about asserting a presence in a neighborhood where we’ve created a lot of ties and where we feel very committed to specific struggles surrounding that very land, that very part of the city.

But the space is not as intensively used or visited as it was two years ago, that’s for sure. It’s continued to function during the pandemic, but in a much more limited capacity. And events like debates, which have been really key to the formation and health of the group, were paused for a long time.

Citygroup's space in the Lower East Side, shown with bulletin by Georgia McGovern. Image credit: Citygroup

Michael: Another one of the initiatives that felt important before the pandemic was a weekly social gathering called circolo where we just gathered in the space and spent time together. The space provided an anchor for us to come together—yes, as architects, but also just as people who didn’t really have a lot of places where we could just gather and enjoy each other’s company. So during circolo we would just eat dumplings, drink some beers, and hang out. We convened over Zoom for a while during the pandemic, which was a nice way to still feel a sense of the group, but everyone got a bit tired of staring at computer screens. We are hoping to host circolo in our space again soon.

It seems like Citygroup is very much a parallel practice, with members continuing to work in other firms. Would you like it to stay that way in the future, or do you hope that Citygroup can become a practice in itself, and perhaps a full-time commitment for some or all of its members?

Violette: That’s a really good question. The idea of it being a full-time commitment is definitely exciting. But at the same time, if we can continue to have a part-time commitment from a lot of people who are genuinely interested in supporting the group’s ideas and work, that doesn’t have to change, as far as I’m concerned. But it would be interesting to see if Citygroup can take on bigger projects.

Will: Part of what makes Citygroup feel magical for me is that it relies on being a parallel practice—people can contribute when they’re able without having to worry about the practical constraints that would otherwise stymie some of the thinking.

But these are the kinds of issues we’re thinking about—like, how can you format requests for exhibition entries to make them manageable for people who might be working a full-time job? How can you ask people to participate in a show in a way that will enable them to do it pretty quickly while still feeling like they’re contributing to something that’s larger than the sum of its parts?

Michael: The question is a really good one, because I imagine everybody who participates in Citygroup has a different answer. I hope, yes, Citygroup can take on bigger projects, but I also hope it never coalesces into something that’s too rigid. Yes, it’s a communal collective effort, but we really encourage disagreement and differing opinions and discourse.

Interview edited and condensed.

Explore

This Land Is Whose Land?

To make infrastructure and industrial sites better neighbors within cities, Landing Studio addresses complex questions of ownership and governance.

Peter Barber: 100 Mile City and Other Stories

The British architect presents his innovative housing projects and speculative urban designs.

Nothing Spectacular

With an ambitious project in southern Florida, Germane Barnes is helping a neighborhood envision a better future.