Following the archaeological discovery of the Clotilda—the slave ship that brought the founders of Africatown to America—local residents hope that cultural tourism will develop into a major source of economic activity.1Learn more about the history of the Clotilda, Africatown, and its community. Mobile-based consultant Nathaniel Patterson and M.O.V.E. Gulf Coast community development corporation president and CEO Vickii Howell examine the economy of Africatown and the region, considering how cultural tourism and related activity could help revitalize a community facing significant financial challenges.

Lessons from the Early Entrepreneurs

The Clotilda Africans knew more about how to live free than how to live as slaves. After being enslaved in present-day Benin in 1860, transported illegally to America, and spending five and a half years in bondage on the Meaher plantation, they found emancipation at the end of the Civil War in 1865. Unable to return home, more than 30 individuals leaned on the skills honed in West Africa (agriculture, crafts, and metallurgy) and their entrepreneurial spirit to thrive, turning their labor into money that they then used to buy land for themselves. This land served two purposes: First, as a place to build homes to live in and second, as an economic base.2Learn more about the development of Africatown and its land use. As the men worked in the numerous small mills that were soon built on Africatown’s waterfront, their wives raised produce on their lands and sold it at market to Blacks as well as whites. Together, they built a community based on a shared economy.

Lessons from this legacy of self-determination and entrepreneurship are the keys to Africatown’s future economic success.

Twentieth Century Shift from Agriculture to Industry

The 20th-century shift from an agrarian to an industrial economy worked both against and for Africatown. The Meahers, still major landholders in the area, leased their lands to paper and lumber mills, railroads, and trucking companies along the waterfront. Breadwinners made good money at the mills, which often hired workers from the neighborhood first. This, in turn, attracted new residents; at one point, Africatown’s 14 neighborhoods swelled to 12,000 people. It was a self-contained community.

Older Africatown residents describe an idyllic community full of well-kept homes and abundant fruit trees, leisure and sustenance fishing and farming, and locally owned businesses that serviced their neighbors. But there were also downsides to the increasing amount of industry: soot dirtied clean clothes on the line, rusted cars, and endangered residents’ health. Nauseating smells emanated from an animal slaughterhouse a quarter-mile away.

Africatown fell into marked decline when a mill owned by International Paper closed in 2000, taking away thousands of direct and indirect jobs. While no new industry has replaced the number of jobs lost, the community is still surrounded by petrochemical companies, paper and lumber mills, railroads, and other “unclean” industries. This part of northern Mobile County is a hub for steel and chemical manufacturing.

Twenty-first Century Industries

Mobile has seen an influx of new industries, most excitingly aerospace: Airbus is the main tenant of the nearby Brookley Aeroplex. Though this facility is only about nine miles from Africatown (and even closer to several other densely populated African American majority census tracts), it doesn’t employ people from those neighborhoods in any significant number.

Left: Airbus at the Brookley Aeroplex. Right: The State Port Authority. Credits: Vickii Howell

The top job-creating industry clusters in the region, according to the Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce, are aerospace and aviation, chemical manufacturing, healthcare, IT/high tech, logistics/distribution, maritime, oil and gas, and steel manufacturing.3Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce, “Industry Clusters,” accessed April 23, 2021. However, in Africatown, according to the US Census Bureau, the top four sectors for employment are education, manufacturing, retail, and healthcare.

There is a clear mismatch between growing, well-paying job sectors and those that employ African Americans. To help close this gap, there must be far more emphasis on educational attainment, industry certification, apprenticeships, and internships, particularly in the region’s Black neighborhoods.

The Next Clean Industry | Visions of Global Cultural Tourism

The discovery of the Clotilda provides Africatown a powerful vehicle to tell and market the community’s story as a means to produce jobs and increase entrepreneurship in the burgeoning “clean industry” of cultural tourism.

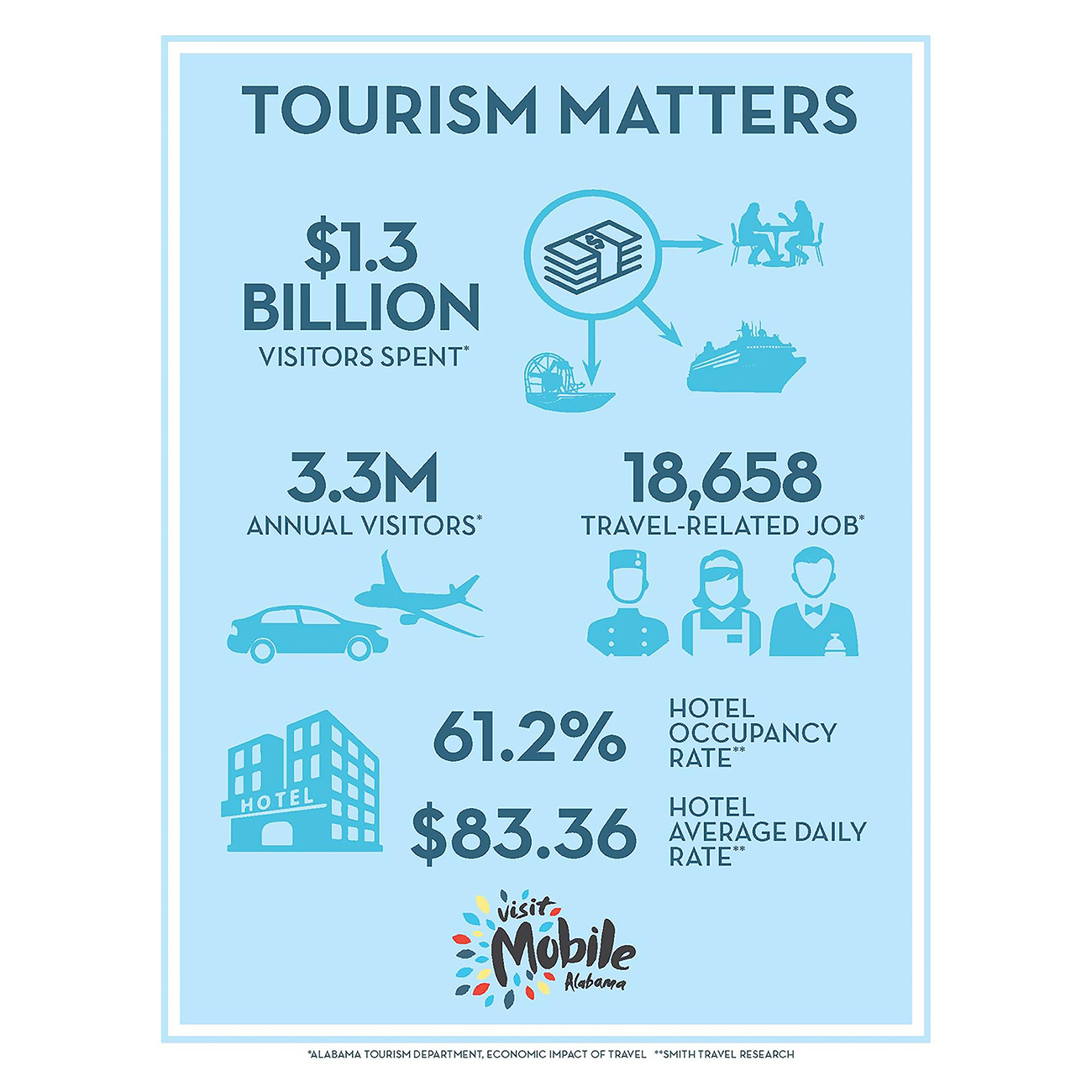

Americans for the Arts defines cultural tourism as rooted in “the mosaic of places, traditions, art forms, celebrations, and experiences that define this nation and its people, reflecting the diversity and character of the United States.”4Americans for the Arts, “Cultural Tourism: Attracting Visitors and Their Spending,” accessed April 23, 2021. The US market for cultural tourism is approximately 130 million people, spending over $171 billion annually.5Cheryl Hargrove, “Cultural Tourism: Attracting Visitors and Their Spending,” Americans for the Arts, accessed April 23, 2021.

In its whitepaper The Real Impact of a Cultural Tourism Strategy, marketing firm The Goss Agency notes that cultural tourism “spreads economic benefits to businesses and people who aren’t included in traditional destination marketing.” Other advantages cited include the promotion of preservation and community beautification, in addition to 38 percent higher spending and 22 percent longer stays per traveler compared to non-cultural tourism.6John Heenan, “The Real Impact of a Cultural Tourism Strategy,” The Goss Agency, accessed April 23, 2021.

African American travelers, who might be particularly interested in the Africatown story, contribute $63 billion to the travel and tourism economy, a $15 billion increase since 2010, according to a 2018 study by Mandala Research. The report found that African Americans partaking in cultural tourism spent more than those traveling for other reasons. Crucially, tourist spending extends beyond specific attractions; among African Americans vacationers, nearly half of all spending is on food and shopping.7Mandala Research, “African American Travel Represents $63 Billion Opportunity,” GlobeNewswire News Room, December 20, 2018.

The Department of Labor’s Occupational Handbook projects favorable employment compensation and hiring growth for cultural tourism jobs such as meeting, convention, and event planners; archivists, curators, and museum workers; and recreation workers.

Attractions such as the Birmingham Civil Rights Heritage Trail, Mississippi Blues Trail, and Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture are examples of popular cultural tourism sites that generate traffic and revenues for the hotel, food, and retail industries.8Martha T. Moore, “Surging Interest in Black History Gives a Lift to Museums, Tourism,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, November 21, 2018.

Of particular note is the National Memorial for Peace and Justice that opened in April 2018 in downtown Montgomery, Alabama, three hours north of Mobile. Known nationally as the National Lynching Memorial, the $20 million complex has tallied more than 400,000 visitors and was named Alabama’s 2019 Attraction of the Year. In 2020, it added a pavilion, restaurant, and performing arts space. The New York Times and Lonely Planet have both cited it as a destination. As a result of this one development, the City of Montgomery has seen a 33 percent increase in lodging tax revenue and, in 2018, a 2 percent increase in sales tax revenue. News reports from 2019 estimate that the site’s economic impact on Montgomery is nearly $1 billion.9The Associated Press, “Alabama Lynching Memorial, Museum Expands,” AL.com, January 19, 2020. See also “Mayor Strange discusses economic impact of EJI museum, memorial” wsfa.com; “Revitalizing Montgomery as It Embraces Its Past,” nytimes.com; “EJI Honored by Montgomery Chamber of Commerce for City’s Tourism Growth,” museumandmemorial.eji.org; “Amid record growth Reed urges uncomfortable change,” montgomeryadvertiser.com.

A Game-Changer

With the right facilities and tourism assets, the Clotilda discovery promises an even greater—in fact, game-changing—economic impact than the Lynching Memorial. City and State tourism officials know this. And so do Africatown leaders.

Cultural tourism opens a window to many business and job possibilities for residents of Africatown and beyond in arts and culture, technology, science, hospitality, services, and recreation. These are sectors where M.O.V.E. Gulf Coast CDC proposes to work with other local nonprofits and educational institutions to create and promote workforce and business development training for Africatown residents and other underserved populations to prepare them for these economic opportunities.

The Descendants’ Motto: "It's Not About the Ship, It's About the People and Their Economy”

Some in the city want Clotilda and Africatown artifacts and documents to be housed in GulfQuest, a maritime museum in downtown Mobile to bolster its flagging revenues. Africatown residents, on the other hand, insist that these collections be located in the community, not only to ensure that revenue from new tourism stays within their historical district, but also to ensure their interpretation is descendant-led.

We want the world to know more about the complete story of the Clotilda and the survivors. We also want community revitalization, economic growth. That means the Africatown International Design Idea architectural competition that’s being planned—a new museum, the Africatown Blueway, whatever is done—we want it done the correct way, and we want the proceeds to revitalize the area.10Vickii Howell, “Discovery of slave ship remains offers pride and proof of ancestors,” The Philadelphia Tribune, June 2019.

—Joycelyn Davis, founder/organizer Spirit of Our Ancestors Festival in Africatown and cofounder of the Clotilda Descendants Association

For more than 40 years, Africatown leaders have talked, dreamed, and presented their ideas to save their community, display their precious archives, and educate the world about their unique American African experience.

In a 1981 Mobile Press-Register article, Henry C. Williams, known as the father of Africatown and president of Africatown’s Progressive League, envisioned a “total historic spot” that could include businesses, a library, a museum, a bank, and perhaps a “little safari or natural park.”11“Africatown Works toward Its Future, Honors Its Past,” Mobile Public Library Digital Collections, accessed April 23, 2021. Then-Prichard Mayor John Smith, who had worked closely with Williams and other Africatown political leaders, saw “the largest Black historic preservation district in the United States,” and the potential for it having a sizable impact on the local economy.

In pairing Historic Africatown with Africatown USA State Park in his city, Mayor Smith also hoped the areas together would become “a regional resource,” with increased commercial developments on the state park and adjoining lands, with more jobs and valuable educational and cultural opportunities for all. The article says about Smith:

He also foresees the growth of the Africatown Folk Festivals … Further, he hopes that African nations such as Ghana, Nigeria and Tanzania will have exhibits at the festivals, and that the events will foster the development of trade relations between those countries and Prichard. “We are maximizing our efforts,” he said, adding that the development of Africatown “is a self-reliant idea without a great deal of federal involvement. That seems to be the idea now, with the Reagan administration.”12“Africatown Works toward Its Future, Honors Its Past,” Mobile Public Library Digital Collections, accessed April 23, 2021.

Now is the time to turn those dreams into reality.

Global Trade and Commerce | The Future of Clean Industries

The Port of Mobile is a major international trade port, connected to primary rail lines and national interstates. The Alabama State Port Authority is among the top five fastest-growing ports in North America.13Dustin Braden, “Slideshow: Fastest-growing North American Ports in 2016,” The Journal of Commerce, May 17, 2017. The proximity of Africatown to the Port, and a new cultural tourism focus on this “African” story, might also be an opportunity to increase international trade, particularly with countries in Africa.

Delegates from Benin unveil signs announcing the Benin House Project with Prichard Mayor Jimmie Gardner in May 2019. The unveiling took place on the day that the Alabama Historical Commission privately announced the Clotilda discovery to Africatown’s community leaders. Credits: Vickii Howell

Countries such as Benin and Ghana have long expressed interest in establishing economic ties with African American communities as a sort of reparations for their roles in the slave trade. The Republic of Benin (inclusive of the former Kingdom of Dahomey, where the Clotilda sailed from) is a major exporter, sending approximately $850 million worth of goods outside its borders each year, including cotton, cashews, shea butter, textiles, palm products, and seafood. Only about 1.8 percent of these goods are exported to North America.14“The economic context of Benin,” Lloyd’s Bank, accessed April 23, 2021.

Representatives from Benin have visited and established relationships with residents of Africatown and the City of Prichard, a predominantly African American city adjacent to Africatown. Prichard’s current mayor has been exploring options to relaunch cultural and commercial exchanges with Benin. The move represents a revisiting of initiatives long advocated for by Black political leaders that have stalled in the past due to lack of public and private funding.15Learn more about such initiatives, such as the Africatown USA State Park.

Eyes on Africatown | Creating a Regional Economic Development Plan Based on Tourism

Africatown leaders have never lacked ideas about community regeneration, that is, the power to dream big and see themselves in charge of their future revitalization. Instead, they have suffered from decades of disinvestment.

Even editors at the Mobile Press-Register took note of this. In a May 2000 editorial article, “At last, AfricaTown may become a showplace,” about recently donated land for the former Welcome Center, they wrote:

Mobile County leaders can look to Selma, Montgomery, and Birmingham to see the historical and economic value of preserving African-American history. All three cities have successfully capitalized on their roles in the civil rights movement of the 1960s, drawing healthy numbers of tourists.

Mobile County, in contrast, has within its borders an unique African-American historical site of considerable significance, but has done little to protect, preserve, and make that history available to the general public.

Development and protection of the area have been slow because efforts mostly have been left to private groups with limited resources, such as the AfricaTown Community Mobilization Group, the recipient of Mr. Leacy’s donation. The donated land may provide equity needed to help move development forward. City and county officials can help secure AfricaTown’s future as a nationally recognized historical site by lending a hand to those working hard to bring AfricaTown back to life.16“At Last, AfricaTown May Become a Showplace,” Mobile Public Library Digital Collections, accessed April 23, 2021.

Now, Africatown leaders need private and public funding to realize their ideas and seize opportunities. To attract investors, Africatown will need an economic development plan that includes market analysis, feasibility studies, projections on wealth creation and revenue generation; investment pro-formas; committed job pipelines for existing industries; and the training of people—and branding of new products and services —for Black cultural heritage tourism in the Mobile area. These workforce and economic development initiatives could be tied to new Africatown cultural institutions being planned, along with many other sites on the Africatown Connections Blueway.

We are aware of the risk that efforts to revive Africatown could lead to increased property values and burdensome property taxes for local landowners in this underserved community. To avoid gentrification and displacement, the Africatown Neighborhood Plan, one of the foundational planning documents backed by the community, suggests that the City place a cap on property taxes for residents. We also suggest the creation of a tax increment financing district or some other policy tool that could capture taxes from new commercial and residential developments in order to ensure sustained economic viability.

Africatown’s Work and Economy Gaps

As a roadmap for future success, the Africatown community—through consortium-building memoranda of understanding among its chief groups and supporting organizations—agrees that work and economy issues in Africatown can only be resolved when the community:

- entrusts the Africatown Heritage Preservation Foundation to represent its interests in the management of Africatown’s narrative, interpretation, trademarking, and branding,

- commissions an Africatown Economic Development Plan with market analysis and feasibility plans for cultural tourism,

- develops an Africatown Entrepreneurship Program with pilot projects for six creative sectors: design, heritage, film, media, performance, and food,

- partners with industry to develop pipeline programs for descendants, modeled on the Harlem Children’s Zone, providing education and jobs to end cycles of poverty,

- fosters relationships with national banks and community development groups to work with the Africatown Heritage Preservation Foundation and other groups to advise residents on real estate economics, wealth management, and financial literacy,

- researches statistics on African American cultural tourism and economic revenue projections, and

- develops an Africatown Community Benefits Agreement for all cultural sites and tourism programs related to Africatown and its history.

Biographies

is chief engagement officer of the company he founded, A Culture of Excellence. A native of Mobile, he attended St. Peter Claver, McGill, and Williamson High Schools before leaving his hometown for California State University, Fullerton. After living in Southern California, Kenya, Brazil, and Tampa Bay, he returned to Mobile in 2011 to take care of his mother. His business acumen was developed while successfully turning around underperforming business units for Los Angeles Times, SCAN Health Plan, and Target, developing high-performing marketing and sales teams for HMOs, and creating highly acknowledged inside sales units for wireless and insurance firms. He began his career as a serial entrepreneur while still a teen, acquiring and merging newspaper delivery routes until he was managing over 20 staff members. He later founded and grew several businesses in sectors including concert promotion, janitorial services, construction cleanup, appraisal services, marketing, and, most recently, a training firm, A Culture of Excellence, LLC. He advocates for small businesses as well as community and economic development and business incubators, serving on more than 25 boards of directors and regional and national leadership councils.

is a journalist, writer, PR strategist, and socially conscious community builder. Upon returning home to Mobile in 2013, Howell joined the Mobile NAACP, becoming its executive director. She is currently the founder and president of M.O.V.E. (Making Opportunities Viable for Everyone) Gulf Coast Community Development Corporation, a nonprofit organization to build collaborative partnerships with businesses, governments, and other nonprofits to create a supportive economic development ecosystem that grows the businesses and socioeconomic capacity of entrepreneurs, workers, and families in historically underserved communities. Read more.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.