When African slaves arrived in the American colonies, they were deprived of the cultural artifacts that had identified them in their homelands. They were stripped from their cultural traditions … and sold bare upon the auction blocks of slave markets. African slaves were even stripped of their names and given new names by slave owners. All visual motifs of identity were stripped as well. Yet while the overt visual symbols and motifs disappeared, intangible traces of identity remained among Americans of African descent. These intangible traces enabled the forging of a new identity of which American slaves are the ancestral authors and contemporary Black Americans are the inheritors.1Mario Gooden, Dark Space: Architecture, Representation, Black identity, (New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2016), 13. —Mario Gooden, author, Dark Space

The Mystical and the Mythical

In writing this report and after conducting extensive research into Deep South traditions and Afrofuturistic possibilities, the editorial team realized that the resurrection of Africatown is impossible without claiming the spirit of this place: that mystical and mythical metaphoric aspect of Africatown’s otherworldly personality.

Africatown is Hallowed Ground. You Can Feel It. | Spiritual Placemaking and Sacred Stuff

Whereas creative placemaking leverages the power of the arts, culture, and creativity to serve a community’s agenda for growth and transformation, spiritual placemaking goes far beyond. In the context of Africatown, spiritual placemaking acknowledges that African culture is deeply embedded in everything the community has birthed and built. It explains the African character and quality of this place; it explains the fragrance of its flowers and the smell of its foods. Spirit rests upon its historic sites where ancestors once trod, and in the cemetery: that African burial ground so far from home. It is in the blood memories of today’s descendants, where vestiges of trauma and sorrow still linger and flow; it hides in their basements and under their beds, where artifacts from enslavement are still secretly secured. As Kern Jackson, a specialist in African American and Southeast folklore and oral narrative at the University of South Alabama, told us in conversation, “Know this—Africatown is about sacred stuff.”

A Good Death

A delegate from Benin visits the Africatown cemetery, bringing gifts to the memorial headstone of Cudjo Lewis. Credit: Vickii Howell

In the beginning, Africatown was a great refuge. Though many African American emancipates had long forgotten Africa, the Clotilda survivors never forgot about home. Heartbroken at not being able to return, they founded their own place where Africans could breathe freely, somewhere they could be their authentic selves.

More than a place, it was a confraternity: an African-centric society formed for cultural and spiritual protection of language and custom. It was established so that its members could remain tied to primarily West African (specifically, Yoruba) religious beliefs, ceremonies, and commitments, even as they conformed to Christian spiritual acts in the church they established: festivals, religious obligations, baptisms, weddings, births, and deaths. Africatown not only enabled the emancipated Africans to own land and build houses, it also was the place where they could maintain their spirituality, their dignity, and their self-esteem in an often-hostile Southern environment.

Like the Brazilian Yoruba Sisterhood of the Boa Morte (Good Death),2Learn more. Africatown’s Yoruba founders knew that they, too, must prepare to die “a good death.” A “good death” meant not suffering the humiliation of dying while shackled and chained: not being treated as mere chattel. The founders were well aware that they would not be buried in the place of their birth—in that hallowed ground of Africa, the seat of the world’s creation story. Many also knew that in the Jim Crow South, marked by lynching and the failures of Reconstruction, some Africatown residents would not be allowed to die a natural death.

All Africans knew that when buried in a foreign land they must die a “good death,” as a free person and free human being. Thus, the historic Africatown cemetery and its forthcoming Welcome Center are of grand spiritual significance: a place for visitors to be introduced to African belief.

We can tell the stories of every individual around this whole community. We are walking storybooks about the community: all the churches, all the people, all the businesses, all those things. We can recreate those things in a very synergizing and energizing way.3Vickii Howell, “Discovery of slave ship remains offers pride and proof of ancestors” The Philadelphia Tribune, Jun 26, 2019, accessed April 28, 2021. See source. —Anderson Flen, president, Mobile County Training School Alumni Association President and cofounder, Africatown Heritage Preservation Foundation

We must not lose sight that to this day, Africatown is a place of cultural intercourse, a place of “double consciousness.” To ensure its continued survival, Africatown still absorbs the values—slings and arrows—of Mobile’s dominant culture. Double consciousness, as articulated by W.E.B. Du Bois in The Souls of Black Folk, is a concept of inward “twoness” experienced by African Americans as a result of racial devaluation and oppression.

Make no mistake about it: Africatown is African, both in functional and biological terms. Cudjo Lewis had twin granddaughters. Not surprising, as natives of Yorubaland (present-day Nigeria) still have the highest rate of twinning in the world. Likewise, Africatown’s rebuilding will require a double exploration: spiritual and physical. Thus, filling in the gaps must go far beyond that mundane design quest for form and function. Rather, the rebuilders must engage descendants, request permission, and then earnestly seek convergence between cultural identity and spiritual being; between cultural voice and community worth; between prevalence of ritual and design of place; between the beauty of well-designed environments and the act of hunting for equity to secure long-overdue economic justice.

We must recreate Africatown as a place for such affirmations—as a spiritual place that knows what the Black body builds, how the Black body uses space, how the Black body heals itself, how the Black body reconstructs dreams, and how the Black body negotiates cultural, political, and economic relationships. All those committed to rebuilding Africatown must clearly understand how the Black body resurrects Black spirit, and how the Black spirit resurrects Black space.

Skill & Build

The plantation landscape was wholly the creation of the slaveholders, but…[the] slaves imbued this landscape with their own meaning.

—On John Michael Vlach’s Back of the Big House: The History of Plantation Architecture4Source: Back cover copy.

The rebuilding of Africatown is much more than bricks and mortar, jobs and statistics, zoning and brownfields, land acquisitions and capital funding commitments. It is about far more than just slapping down some shotgun houses and a series of prefabricated buildings and calling it done. It is about respect for the authenticity of African spirit, and commitment to that authenticity by everyone involved in planning, design, and development. If Africatown is to thrive, then we all must embody the sacred in all that we build.

Africatown community meeting in July 2019, when the community says “Yes!” to moving forward with The Africatown International Design Idea Competition. Credit: Vickii Howell

Architecturally, this means we have an incredible opportunity. It means we get to color outside the lines of numbing architectural uniformity. It means we can conjure up the visual pattern languages of the ancestors by researching African aesthetics and cultural anthropology. And it means we can build an African community that serves as the embodiment of both African history and African visual vocabularies, and one that pleases the kinesthetic senses (sight, taste, touch, smell, sound) to become that highly regarded spiritual place.

For decades, Lorna Woods, an elder from Lewis Quarters, told the story of her ancestors to virtually anyone who would listen. One person who did listen was William Bates, an African American architect and past president of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) who came to Africatown at the invitation of the Africatown International Design Idea Competition’s organizers. Bill rode on the van next to Miss Lorna and was touched by her sense of history and excited by the possibility of design contributing to the rebirth of this community. The AIA soon became an early competition sponsor.

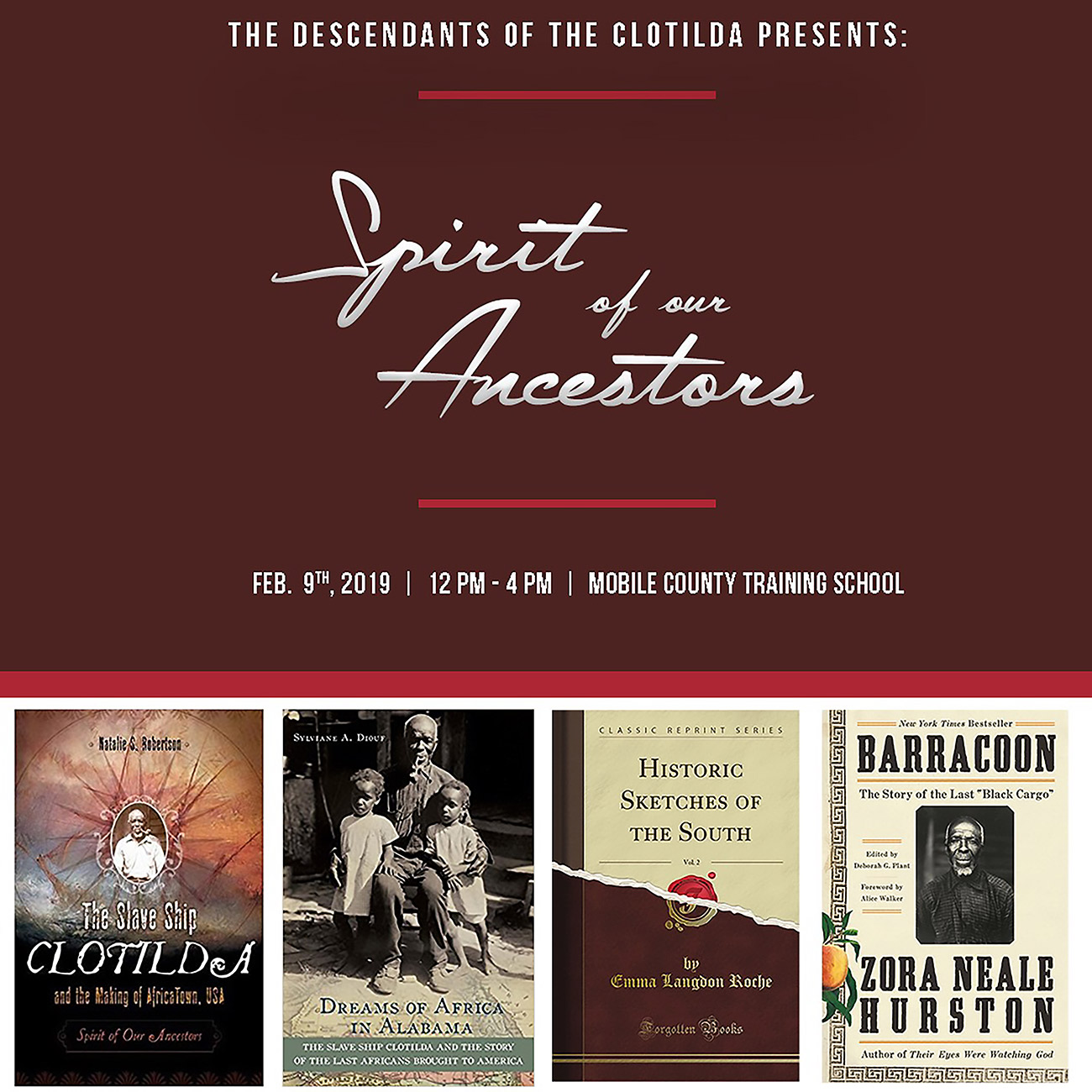

"I don't know how people feel about spirits or their ancestors, but I just feel like my grandmother, my great grandmother are pushing me to be the next in line as family historian from cousin [Lorna Woods]." —Joycelyn Davis, founder and organizer Spirit of Our Ancestors Festival

While preserving Africatown’s history, we must also invest in a future that generates a new authenticity: one that recognizes the dreams that got suppressed and left behind, as well as the dreams of endless possibility. We know that the African imagination has no bounds: This is what our children and our children’s children must be retaught.

No Small Idea

We hope that this report leads to a deeper understanding of the African worldview, so often overlooked by the dominant culture, and by well-meaning yet casual passersby. Africatown represents utopia for its founders and for its descendants. Africatown is no small idea. Now is the time for ideas and ideals that stir human souls.

We see the resurrection of Africatown as one grand, nationally endowed humanities exhibition tied to method, technique, rubric, and curatorial tradecraft that brings to life the memorialized Africatown Cultural Mile. Realizing this goal will require the convergence of new imaginative practices and public commitments to funding, while calling on the talents and energies of spiritual and technical initiates: those still committed to holding up the bloodstained banner of progress for the only nineteenth century African-built settlement in the United States of America.

Biographies

(Associate AIA/NOMA) is an urban designer, master planner, and the CEO of studiorotan, a cultural heritage/civic design firm. She is the first African American woman to graduate from Syracuse University with a bachelor’s degree in architecture. She attended London’s Architectural Association and graduated from Columbia University with a master’s in urban and regional planning. Kemp-Rotan is currently the professional competition advisor for The Africatown International Design Idea Competition. Read more.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.