Republic Iron and Steel Works, Youngstown, Ohio, in the early 1900s. Courtesy In the Mahoning Valley editorial team

A Legacy of Industry

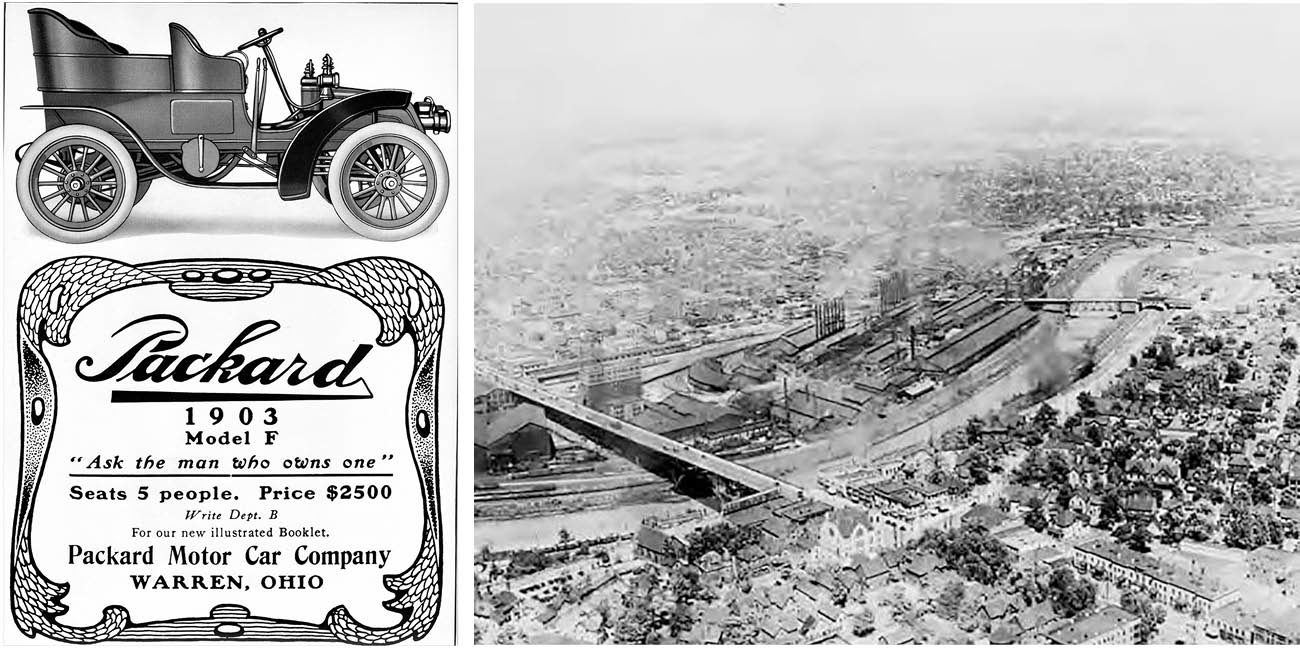

In 1890, when James Ward Packard and his brother Will opened the Packard Motor Car Company on Dana Street, Warren, Ohio, became one of the first locations in the US to manufacture cars. For Warren, located in northeast Ohio’s Mahoning Valley, Packard vehicle production was just a chapter in its storied history of manufacturing. With large deposits of iron and coal, the area has long been a site for industrial production: iron, ammunition and other necessities for the Union during the American Civil War, and later (and most famously) steel.

In the 1890s, coinciding with the growth of Packard, local industrial production began to shift from iron to steel. Since then, steel production, the manufacturing of cars, and other forms of industry have been central to the identity and character of the region. Industrial sites have affected everything from the environmental condition of the Mahoning River to transportation networks and housing, public space, and social structures.

Steel mills began to dot the valley after the 1890s, often located along the river for easy access to water to cool down blast furnaces and equipment. As many as 27 steel mill structures, some towering as high as 12 stories, were built in the area. Some of the industrial complexes dwarf the surrounding neighborhoods. The Copperweld Steel site in northern Warren, for example, spreads over 10 million square feet, including furnaces, fabrication, storage, and environmental treatment areas.

Left: 1903 advertising for the Packard Model F, made in Warren, Ohio. Credit: Flickr collection of Alden Jewell. Right: Aerial view of Republic Steel in Youngstown, Ohio, 1934. Credit: Cleveland Memory Project

Quick growth in the steel industry meant equally quick growth in population. Youngstown grew from 30,000 residents in 1890 to over 170,000 by 1930. This large influx of people included both European immigrants, especially from Italy, Poland, and Hungary, and a large African American community, moving north from southern states looking for jobs and opportunity especially in the wake of the National Origins Act of 1924 that limited foreign immigration.1The National Origins Act, also known as the Immigration Act of 1924 created immigration quotas by nation as well as restrictions that dramatically slowed down immigration. “Closing the Door on Immigration (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. See source.

This rapid growth forced companies like the Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company to build housing near their plants. Similarly, communities all over the Mahoning Valley provided pathways to prosperity and a middle-class life by building housing and creating public amenities such as robust parks and public transportation networks.

Map of the Mahoning Valley. Credit: In the Mahoning Valley editorial team

The Mahoning Valley was hit hard by the Great Depression, revealing the risks of relying so heavily on a few industries.

By 1942 the steel industry had recovered and was quickly expanding by providing steel during World War II. This expansion continued through the 1950s, a period in which the US steel industry faced little international competition.

However, by the 1970s, technological advances and foreign competition began to hit, creating pressure in the Mahoning Valley to adapt and diversify, which it failed to do. These pressures burst into the open on September 19, 1977, a day known in the area as Black Monday. On that Monday, as people began to file in to start their morning shifts, the US Steel company announced it was furloughing 5,000 workers immediately.

Within a decade of these initial job losses, the Mahoning Valley lost an additional 40,000 jobs and 50,000 people left the area.

Left: Abandoned facility of the Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company, 2006. Credit: Stuart Spivack via CC BY-SA 2.0. Right: Artist George Segal’s 2002 sculpture “The Steelmakers,” Youngstown, Ohio. Credit: In the Mahoning Valley editorial team

Slowly these once-humming plants shut down, leaving behind large empty sites and buildings. In parallel, the loss of population left surrounding communities both shrinking—with increasing numbers of vacant houses and overgrown, underused infrastructure—and poorer, with fewer economic opportunities for residents.

This cycle of decline continues today.

Warren, Ohio: A Case Study of Industrial Decline

To see the extent of what was lost when the steel industry collapsed and what has come to fill the vacancies, let’s take a look at Warren and its immediate surroundings. As described above, Warren was the site of one of the earliest industrial zones dedicated to car manufacturing, the Golden Triangle. This area was created in the late 1800s and is today mostly filled with companies specializing in tin and packaging. As a historic industrial site, it is surrounded by residential communities, and even has a regional bike greenway crossing through. Yet the Golden Triangle remains disconnected from the urban fabric of the region.

Joining the Golden Triangle at Warren’s northern and southern borders, there are two other major industrial sites along the Mahoning River. The large Copperweld site is located on its northernmost border. Opened in 1939 by the Copperweld Steel Company, the company thrived for decades manufacturing steel billets both for the war effort and the postwar economic boom. However, the company went bankrupt in 1999 as steel production continued to move to other countries. Since then, it has seen numerous owners with extended periods of intermittent vacancy. Currently, part of the plant is used by the Ohio Star Forge Company to create steel parts for the automotive, industrial, and energy sectors. The majority of the site, however, continues to lie vacant, with many of its structures empty and slowly rusting. Part of the Copperweld company was turned into Warren Steel, which produced steel at the site on and off until as recently as 2015.

Adding pressure to the situation, the vacant areas of the Copperweld site have been affected by fraud and environmental cleanup lawsuits. For now, the site remains mostly vacant, unable to be occupied while toxic chemicals, oil pits, and other hazardous materials remain.

On the southern side of Warren, the 1,200-acre BDM site sits on the eastern edge of the Mahoning River. This site was once owned by the Republic Steel Corporation and most of the buildings have been demolished and a thorough environmental cleanup project has been completed. The site, which is within an Opportunity Zone—a federal program that incentivizes development through preferential tax treatment in economically distressed communities—and BDM currently sits waiting for new investments.

Brownfield and abandoned structures at Copperweld Site, Warren, Ohio. Credit: In the Mahoning Valley editorial team

Beyond these troubled industrial sites, Warren contends with large numbers of vacant houses and an infrastructure built for a much larger population. Established in 1801 within what was then the Connecticut Western Reserve,2See source. Warren’s downtown would feel at home in any New England town. Many of the residential areas contain large houses built for the many who grew wealthy during the city’s boom years. Two of the richest families in town, the Perkinses and the Packards, donated large tracts of land to create parks alongside the river that connect the river banks to downtown with tree-lined boulevards.

This legacy built environment belies the city’s troubles. Vacant houses have been used for illicit activity or simply left to rot. The collapse of industry and postwar white flight to local suburbs left the areas closest to downtown poorer. The result: a disconnected community with unequally distributed investment and clear divisions of race and class. In the summer of 2020, Warren, like other cities in the Mahoning Valley, declared racism a public health emergency, in part to confront this inequality.

Watch The Place That Makes Us, a recent documentary profiling Youngstown residents, as they work to revitalize their hometown.

The Mahoning Valley Looks Forward

To deal with residential and industrial vacancy, local organizations and foundations in Warren created the Trumbull Neighborhood Partnership (TNP), which now serves the dual functions of community development corporation and land bank. For about a decade, TNP has demolished and renovated building stock and helped match new recreational and productive programs with formally vacant land. It does this while also fulfilling other social needs and creating jobs in the community through its Building A Better Warren program. TNP, its partners, and other organizations in Warren and Youngstown are beginning to show the way forward for these communities.

In this context of community and grassroots efforts to reverse, or at least halt, the region’s decline, the 2019 announcement that the General Motors Assembly plant in Lordstown was closing hit the Mahoning Valley community hard. The 6.2 million square foot plant, built on 905 acres of former farmland, was in operation from 1955 to 2019. Although there is movement to reopen parts of the plant for the manufacture of electric vehicles and components, and LG and GM have started building a new electric battery plant in the area, the future of industry and jobs in the Mahoning Valley is unclear.

The plant closure is also an important reminder that the region continues to be dependent on only a few industries for its economic well-being. The consequences of such economic monocultures are made clear in a 2019 study prepared by Cleveland State University’s Iryna Lendel, Merissa Piazza, and Matthew Ellerbrock.3Cleveland State University, “Lordstown GM Plant Closure Economic Impact Study,” by Iryna Lendel et. al., accessed April 5, 2021. They estimate that the Lordstown plant closure will result in an overall loss of approximately 3,000 jobs and $300,000 in income tax revenues for the surrounding communities.

This Report

Given the history and urban realities of the Mahoning Valley and its communities, including Lordstown, Warren, Youngstown, and smaller villages like Lowellville, we frame this report through the lens of the area’s industrial, economic, and labor histories, exploring how those have shaped the area’s present identity and what potential futures may look like.

Map of the Mahoning Valley illustrating sites discussed throughout this report. Credit: In the Mahoning Valley editorial team

In this report, we present innovative new ideas being developed in the Mahoning Valley, such as experiments in reimagining the role of rivers, health institutions, land banks, and governments in building community wealth opportunities. We share new models for community-based educational pipelines and employee-owned cooperatives trying to reimagine the economic future of the area. Leaders in the community, such as Jennifer Roller, president of the Raymond John Wean Foundation, give a holistic vision for the future of the Valley. We hope to provide a glimpse into how this area is actively rethinking and negotiating its social, economic, environmental, and spatial futures—while confronting legacy issues common to many American communities around loss of industrial base, poverty, segregation, and disinvestment.

What the Mahoning Valley has seen is not entirely unique in the United States, and like many other places, the region is looking for a way forward. Among the most exciting things happening in the area are experiments with community and collective efforts as a way to change economic and social conditions. In this way, the Mahoning Valley might once again point to new futures, as it did during its heyday of steel and automobiles.

Biographies

is an associate director of Kent State University’s Cleveland Urban Design Collaborative (CUDC), where he provides strategy and design coordination for the CUDC’s urban design, applied research, engagement, publication, and academic activities. Riano is also the founder and lead designer of DSGN AGNC, a design studio exploring new forms of political engagement and co-creation through architecture, urbanism, landscapes, and art. He teaches graduate architecture and urban design studios at Kent State University and has also taught design studios at Harvard University, Carleton University, Columbia University, Parsons The New School of Design, The Pratt Institute, Syracuse University, Wentworth Institute of Technology, and the City College of New York. Riano holds a bachelor’s degree in design from the University of Florida and a master’s in architecture from the Harvard University Graduate School of Design (GSD).

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.

Select Bibliography

Beverly, Michael A. “African-American Experience in Youngstown 1940-1965.” Youngstown State University, 2002.

Boney, Stan. “Last Blast Furnace in Warren Torn down after 96 Years.” WKBN News. October 29, 2017. http://beltmag.com/losing-lordstown-gm-plant-closing/.

Guerrieri, Vince. “Losing Lordstown.” Belt Magazine, December 17, 2018. http://beltmag.com/losing-lordstown-gm-plant-closing/.

Guerrieri, Vince. “On The 40th Anniversary Of Youngstown’s ‘Black Monday,’ An Oral History.” Belt Magazine, December 20, 2018. https://beltmag.com/40th-anniversary-youngstowns-black-monday-oral-history/.

Cleveland State University. “Lordstown GM Plant Closure Economic Impact Study.” Authors: Iryna Lendel, Merissa Piazza, and Matthew Ellerbrock. Accessed April 4, 2021. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/urban_facpub/1592.

O’Brien, Dan. “Left to Rot, an Environmental Mess.” Business Journal Daily | The Youngstown Publishing Company, October 14, 2020. https://businessjournaldaily.com/article/left-to-rot-an-environmental-mess/

Russo, John, and Sherry Lee Linkon. “The Social Costs Of Deindustrialization.” YSU Center for Working Class Studies, May 15, 2020. https://ysu.edu/center-working-class-studies/social-costs-deindustrialization.

WKBN News. “Warren City Council Set to Vote on Declaring Racism a Public Health Crisis.” June 23, 2020. https://www.wkbn.com/news/local-news/warren-city-council-set-to-vote-on-declaring-racism-a-public-health-crisis/.

Zito, Salena. “The Day That Destroyed the Working Class and Sowed the Seeds of Trump.” New York Post, September 18, 2017. https://nypost.com/2017/09/16/the-day-that-destroyed-the-working-class-and-sowed-the-seeds-for-trump/.