From Studio Ames, a Design Prompted by New York City’s Housing and Climate Crises

Daisy Ames discusses a speculative residential project designed for a site in the Bronx.

October 13, 2023

Rendering of the shared courtyard of Studio Ames’s Bronx collective housing project. Image credit: Studio Ames

Studio Ames is a 2023 League Prize winner.

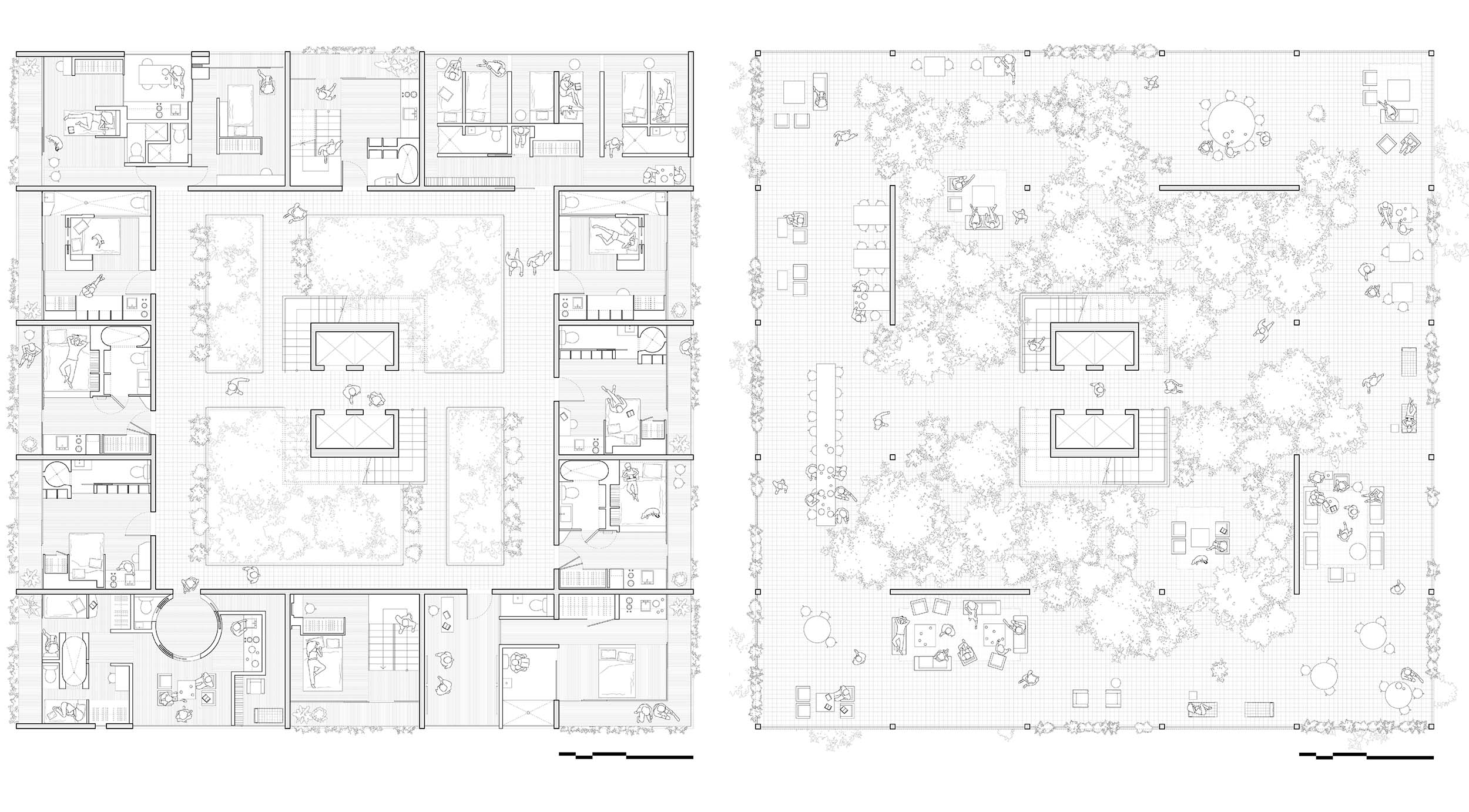

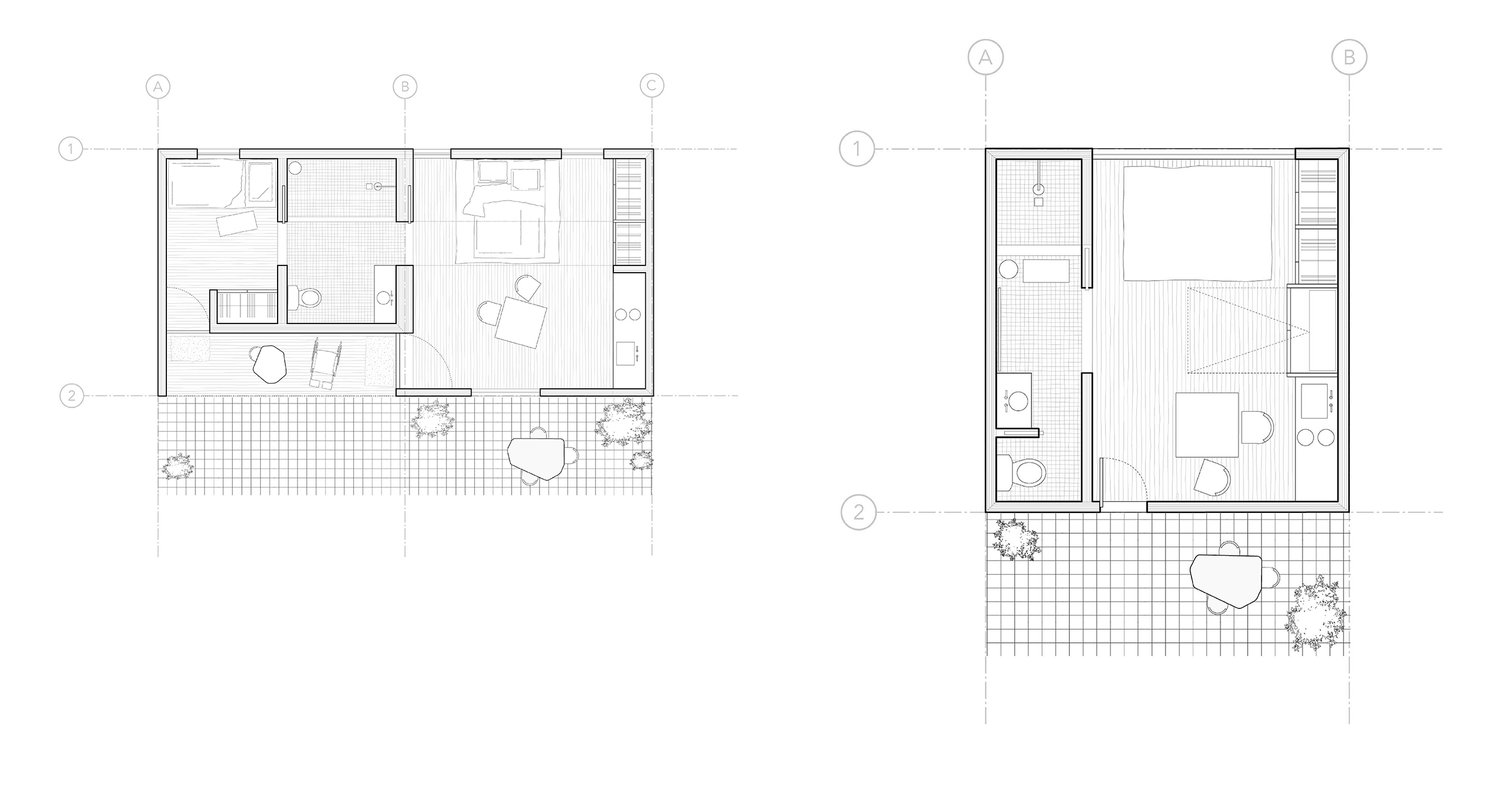

Founded in 2017, Studio Ames is a New York City–based research and design practice focused on the housing crisis and climate change. The firm’s output includes a series of speculative projects building on investigations of local and international housing policies as well as design and construction practices. One of these, a collective housing building in the Bronx, envisions a low-rise, high-density structure focused on natural light and cross ventilation, with modular construction accommodating a range of living arrangements, from dormitories to assisted living units.

The League’s Rafi Lehmann spoke with Daisy Ames about the project.

*

Rafi Lehmann: Your practice has been invested in developing housing solutions for several years now. How did this particular project start?

Daisy Ames: Some of the original ideas came from a 2016 invitation from the Storefront for Art and Architecture. It was an exhibition called Work in Progress where they invited 26 artists and architects to propose alternative visions for current construction sites in the city.

At the time, I was in my first year of teaching at Rice School of Architecture. The pedagogical atmosphere encouraged me to take a closer look at models of housing and sustainable construction processes.

NYU Furman Center had just published a white paper on micro units, advocating for them as a good option for affordable housing, arguing that the smaller the unit, the cheaper you can rent it out.

And I was also motivated by mass timber construction emerging in the United States. I wanted to develop a modular, yet adaptable mass timber system that could be used for housing, and I was committed to the housing project providing beautiful, healthy living interior spaces and ample shared spaces. I believe that good design should be accessible, and my way of responding to the housing crisis is by applying good design that incorporates innovative green solutions for the residents.

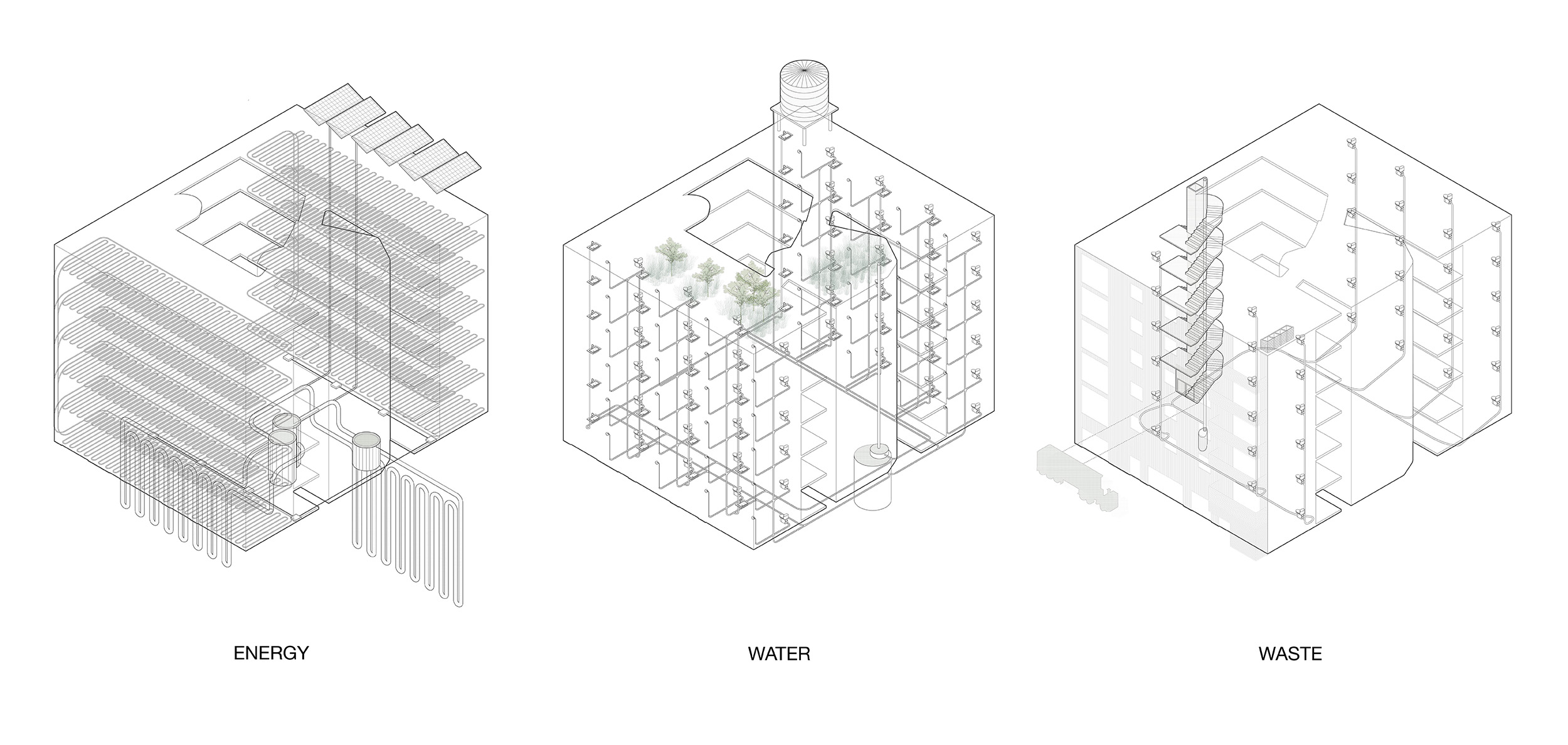

So I designed a speculative housing project on a construction site along the Hudson River that was to be made out of mass timber and composed of variations of micro units.

While the Storefront for Art and Architecture only asked for a rendering for the exhibition, I became curious about how this building might actually work, so I started to draw plans and sections to better understand how micro units could function, and how building with wood impacts interior spaces.

And so that 2016 prompt from the Storefront for Art and Architecture really spurred the thinking that I’ve carried forward in my practice since then.

Lehmann: In terms of the Bronx housing project, since the project is speculative, how did you choose the site for the building?

Ames: The site is on Weeks Avenue in the Bronx. I taught a studio that looked at a whole block just down the street, near Claremont Park. I was exploring the area with students and having conversations about the different housing typologies: rowhouses, townhouses, prewar buildings, late 1800s buildings, 1901 New Law buildings, and inclusionary housing. I saw this really wide, lovely site, and I began to imagine what kinds of innovative housing projects might work there.

Rendering of the facade of Studio Ames’s speculative Bronx collective housing project. Image credit: Studio Ames

Lehmann: In your League Prize competition entry, you wrote that this project was influenced by research you conducted in Scandinavia while on a Stewardson Keefe Le Brun Travel Grant from the Center for Architecture and AIA New York. Can you say more about how these travels influenced the building’s design?

Ames: Well, I was interested in conducting research in Scandinavian countries because they’ve been using mass timber to create housing for decades. They also are at the forefront of innovating sustainable policies in terms of energy and waste, as well as collective living spaces.

For example, in Sweden, they have a performance-based design sensibility. So rather than having prescriptive building codes, the building industry supports projects that benefit from innovative construction methodologies. This allows architects and builders to collaborate in ways that are uncommon in the United States. They are innovating together to improve existing processes of construction.

And then in Denmark, there’s a real emphasis on the lifecycle of buildings. For decades, the Danish government has been working on urban renewal projects that renovate and upgrade old social and postwar housing. The focus on renovation and affordability within the city center allows individuals to age in place.

Innovation and restoration are two different approaches that are applied in different circumstances, and yet they are effective strategies used in Sweden and Denmark to address the housing crisis.

Lehmann: Can you tell me more about the sustainability strategies you envisioned for this project?

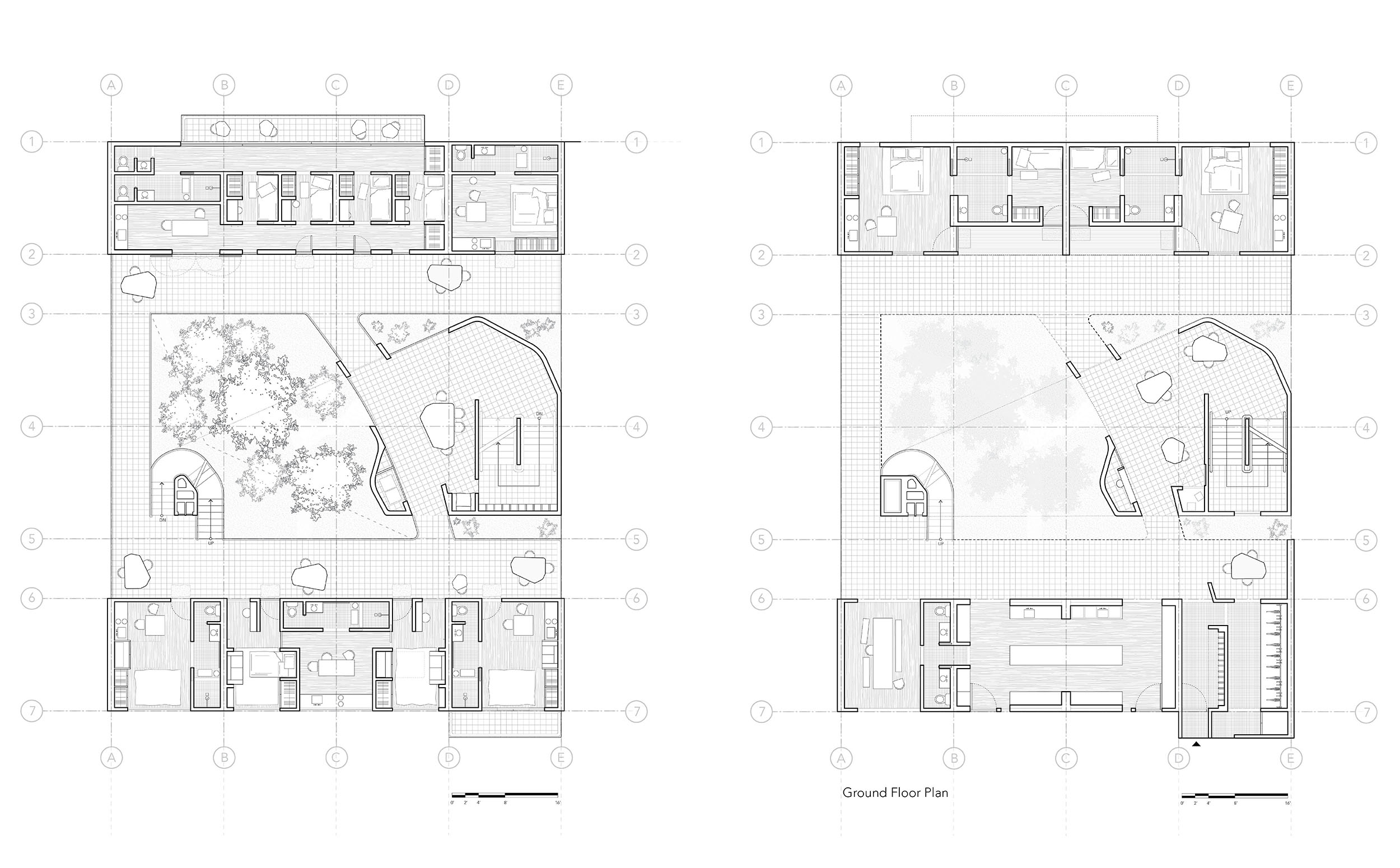

Ames: I wanted to explore waste, water, energy, air, and labor. I’m always thinking about things that are purposely hidden out of view. Many of the representations of Studio Ames consider these conditions as an effective means to rethink or improve elements that are typically within the floor plate, the walls, and the ceiling.

In terms of energy, this project incorporates methods for moving away from fossil fuels and status quo construction methodologies. For example, the building is equipped with solar panels to reduce the use of brown power from the grid, and it also uses a vertical geothermal heating and cooling system.

The project also supports new processes and policies that integrate better waste management and resource recycling. So it integrates a number of different ways to sort disposables, including compost, glass, and plastics, within the systems of the building.

In terms of air, this building revisits the principles of the 1901 New Law Tenement Act. This was one of the first policies to promote cross ventilation, light, and air as important parts of housing health. I was keen to incorporate these aspects into this design, ensuring that all units could be opened from one side to the other.

Water management–wise, the project is proposing a cyclical water system whereby stormwater is collected and reused to water plants.

And, of course, my practice has always valued mass timber construction. Sourcing local, renewable material eliminates other often-invisible components of architectural production, which are the intense extraction process of steel and concrete and the labor practices of other locations doing that work.

Renderings of the Bronx Housing project unit interior and extended corridors. Image credits: Studio Ames

Lehmann: The Bronx building is obviously very different from the typical New York City apartment building, but could you say more about how these differences might play out at the level of policy or financing? How does this compare to status quo New York development today?

Ames: Yes, it is very different than a typical apartment building, mainly because of the building material and abundance of public space.

It was only in October 2022 that the New York City building code added cross-laminated timber (CLT) and structural composite lumber (SCL) as acceptable building materials for construction. Whereas in Sweden, again, the use of mass timber for housing has been innovated for years and applied into beautiful, sustainable designs. In Stockholm, I visited a prefabricated cross-laminated timber housing project called the Cedar House being built by Folkhem, a Swedish developer. It is an amazing project with an environmentally minded design in terms of building materials as well as the beauty and health of the indoor living spaces.

The ample shared spaces are also a major differentiator compared to typical development in New York. In typical housing projects, the pro forma dictates a project’s profitability. As a result, corridors are often very narrow and long and the stairwells are reserved for fire egress and relegated to corners of the building. This is not conducive to creating a comfortable experience, and I wanted to create something that had the residents’ daily rituals in mind.

So the project supports new innovation in mass timber as a viable solution in New York City, and it supports creating spaces that are unique, open, and full of natural elements.

Plans of an assisted living unit and individual unit in the Bronx residential project. Image credit: Studio Ames

Lehmann: Do you think it’s feasible that a project this innovative could get built in New York’s current environment?

Ames: Absolutely. I think it’s really basic and fundamental that we would provide much-needed housing options. The fact that it is really hard to find accommodation in New York City speaks to underpinnings that drive housing here.

So I think there’s an opportunity to build these kinds of buildings. The micro unit is something that can be applied to other sites—even to irregular small lots throughout the city. I think there’s another version of this project that can address infill lots. If we have a base and that base can be doubled or tripled, we have a few different ways that smaller buildings can be made on smaller sites, and the spaces between the lot line and the units themselves can be the shared space.

The elephants in the room are money and policy. I think that we really need policy to incentivize developers to invest in new housing.

Interview edited and condensed.

Explore

Peter Barber: 100 Mile City and Other Stories

The British architect presents his innovative housing projects and speculative urban designs.

The Housing System: New methods, new materials

Are technological and material advances leading to a radical change in the way we design and build housing?

City as living room: Single and shared housing in the Bronx

For the Making Room design study, Team 8 designed housing for underused sites along the Grand Concourse.