Margaret Morton was awarded a New York State Council on the Arts independent project grant in 2007 sponsored by The Architectural League. The funding allowed her to prepare her photographs of nomadic Kyrgyz burial settlements for a book and exhibition.

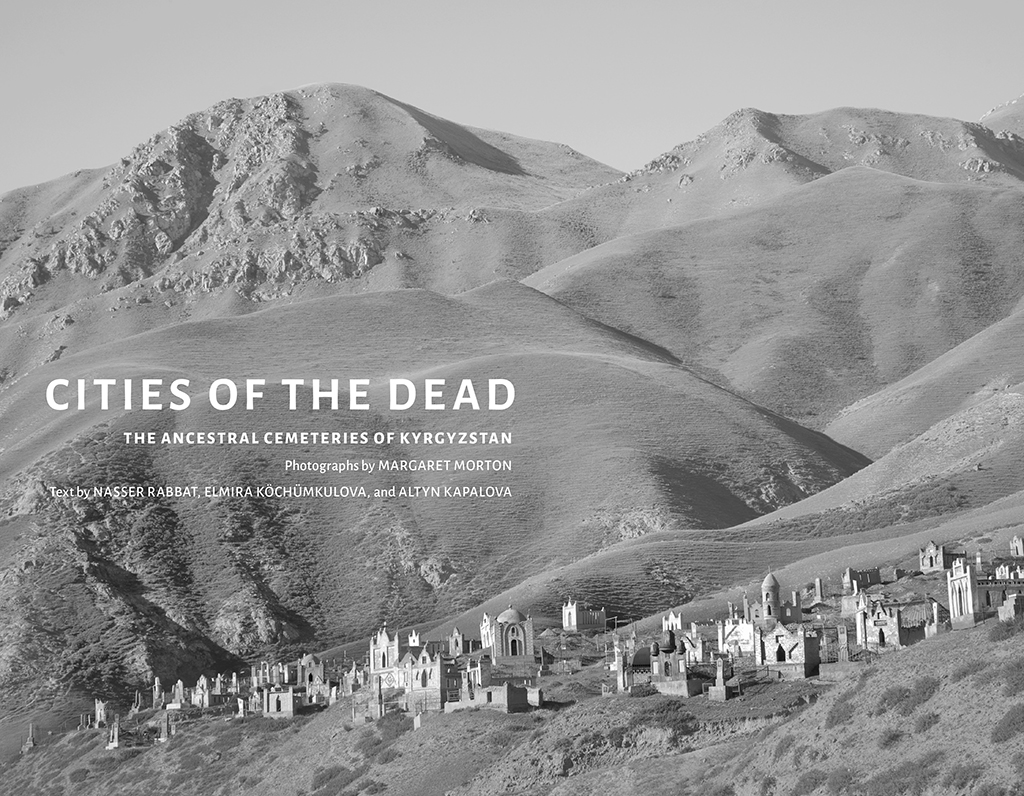

A Kyrgyz ancestral cemetery seen from a distance is astonishing. At first it might seem a mirage, the ornate domes and minarets are so completely at odds with the desolate mountain landscape. Miniature cities appear unexpectedly on the edges of inaccessible cliffs or stretch along deserted roads. As one approaches, the scale contracts. The opulent structures are surprisingly smaller than they seemed from afar. Graceful crescent moons float above cupolas and peaked towers, balanced on fragile metal rods. Within the walls, scattered among the imposing mausoleums, delicate metal frames replicate yurts, peopled only by small metal portraits of the deceased and overgrown with weeds, for it is not Kyrgyz custom for the living to frequent the graves of the dead.

—Prologue to Cities of the Dead

My first trip to Kyrgyzstan was in July 2006, with Manhattan theater director Virlana Tkacz, who invited me to photograph sites referenced in a Kyrgyz poem that she was developing into a theater piece. We were traveling along a deserted road, when a magnificent city suddenly came into view. But as we drove past, the majestic forms compressed and flattened. I was transfixed by the illusion.

In fact, it was a Kyrgyz cemetery. Determined to photograph additional sites, I postponed my flight and extended my stay from six to ten weeks. It was clear that there were regional differences, which would be important to record. A research and travel grant from the Graham Foundation supported two more summers of travel throughout Kyrgyzstan and a NYSCA grant funded photographic printing and preparation of a book and exhibition, Cities of the Dead: The Ancestral Cemeteries of Kyrgyzstan.

The cemeteries of Kyrgyzstan are architecturally distinctive and culturally revealing. Unlike other Muslim cultures, where religious laws forbidding high tombs and markings on graves are strictly observed, Kyrgyz traditionally mark their graves with a variety of structures to honor and remember the deceased. The majority of Kyrgyz cemeteries present the complex nature of the people’s religious and cultural identity and include many “un-Islamic” motifs based on pre-Islamic beliefs in animism, shamanism, and ancestor worship, which combine with Islamic and Sufic and, in more recent years, Russian and Soviet influences.

In Central Asia, the tradition of building elaborate mausoleums in the style of mosques for well-known tribal leaders, heroes, khans, and descendants of Prophet Mohammed is influenced by Islamic tradition, especially Sufism. There are hundreds of tombs of well-known Sufi pirs, or masters and historical leaders, throughout Central Asia, most notably in Samarqand. If in the past monuments were erected only for well-known tribal leaders, khans, poets, and saints, eventually they were constructed for all those who could afford them. Family members built small-scale mausoleums for their deceased. These personal memorials, clustered on their tribal lands and traditionally assembled and decorated by hand, are the subjects of my book.

During the seven decades of Soviet-led secularization and de-Islamization of Central Asia, most of the country’s mosques were destroyed or turned into public buildings. The Muslim cemeteries, however, survived unscathed. Local state officials and Muslim clergy rarely interfered with people’s traditional customs, especially the life cycle ceremonies, including funerals in rural areas.

Nomadic influences are evident in the sites where Kyrgyz typically choose to bury their dead: an elevated area such as a hilltop or mountain pass, along rivers, or near sacred lakes and springs.

For centuries, the yurt — or boz üy, as the Kyrgyz say, which literally translates as “gray house” to describe the gray felt covering — has been integral to Kyrgyz nomadic culture. During the 1930s, due to Stalin’s sedentarization policy, the Kyrgyz and the other nomadic peoples of Central Asia were forced to give up their nomadic life and traditional yurt dwellings to live on collective farms. Yurts were rarely used during the Soviet period, except for funeral rituals.

Today, yurts house herders and their families in the summer and also are used for special occasions, such as family feasts, weddings and anniversaries, national celebrations, and, most importantly, funerals.

“A Kyrgyz is born in the yurt and will die in the yurt.” —traditional Kyrgyz saying

Yurt cemetery monuments are made of metal instead of the traditional felt-covered wood frame and are smaller than regular yurts. They are usually topped with the Islamic star and crescent moon, although scholars are quick to point out that the Turkic peoples of Central Asia also used these celestial symbols in their worship of the sky, moon, and stars.

The tunduk, or roof wheel, is the round wooden structure on top of the yurt through which sunlight and fresh air enter and smoke from the fire escapes. The tunduk wheel is an essential symbol of the Kyrgyz, and after the 1991 independence was chosen as part of the emblem on the Kyrgyz Republic’s national flag. The tunduk also is replicated in cemeteries, sometimes combined with the crescent moon.

Kyrgyzstan’s nomadic culture also is expressed through representations of eagles and horses, often perched atop or combined with traditional Islamic forms, or in tomb paintings of the deceased on horseback, preparing to hunt with an eagle. Kyrgyz continue to be known throughout Central Asia for the beauty and speed of their horses, and their own skill as horsemen. Eagles are still used for hunting in some parts of Kyrgyzstan, captured at birth and trained to hunt wolves and smaller prey.

Nomadic beliefs in nature worship continue to pervade Kyrgyz burial traditions. This is most evident in the deer antlers extending eerily from Islamic architectural forms in the northern region settled by a tribe known as the Deer People. In remote regions bordering Uzbekistan, skulls and horns of high mountain sheep and a variety of mountain goats are prevalent.

Some cemeteries bordering Uzbekistan and Tajikistan have a distinct feature not seen in other regions. Tails from yaks, large animals found in the high mountains, can be found swaying from tall, hand-hewed wood posts that mark the head of the graves.

Although I rarely encountered Kyrgyz people in the cemeteries, horses, donkeys, and cows quietly grazed where walls had crumbled. Snakes sunned themselves on burial mounds; crows circled overhead. Most Kyrgyz believe that the monuments should disappear back into the earth with the passage of time so renovating or repairing old or damaged tombs and grave monuments is discouraged. While visiting more recent gravesites, I saw many unmarked graves with only simple mounds or with very few markers.

“As our region wrestles with emerging contemporary cultural identities, it will be difficult to predict what the architectural style of Kyrgyz cemeteries will be ten or twenty years from now,” explains Dr. Elmira Köchümkulova, the Kyrgyz anthropologist who contributed the introduction to the book. “Newer graves are starker, with few markers. This book provides a unique and valuable record of an unexpected archive of Kyrgyz cultural history.”

Cities of the Dead: The Ancestral Cemeteries of Kyrgyzstan

Cities of the Dead: The Ancestral Cemeteries of Kyrgyzstan was published by University of Washington Press in November 2014.

The above text is based on personal observations and research, conversations, and site visits with Kyrgyz anthropologist Dr. Elmira Köchümkulova and art historian and anthropologist Altyn Kapalova, who both contributed essays to the book. Nasser Rabbat, Aga Khan Professor and Director of the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture at MIT, contributed the preface, which was reprinted from his introduction to the MIT School of Architecture exhibition in 2011.

Cities of the Dead: The Ancestral Cemeteries of Kyrgyzstan, 2007. Credit: Margaret Morton, all rights reserved

Support

Morton’s travel and research for Cities of the Dead were supported in part by the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts. Additional travel and research support was provided through Yara Arts Group and the University of Central Asia. Morton’s photographic printing and book preparation were supported in part by a New York State Council on the Arts Architecture + Design independent project grant, sponsored by The Architectural League of New York. The book’s publication was supported by The Christensen Fund and the University of Central Asia.

Biographies

Margaret Morton has been engaged with the photographic representation of alternative built environments for 25 years. Her four previous books form a permanent record of the temporary habitats that Manhattan’s homeless individuals created for themselves in public parks, vacant lots, abandoned buildings, along the waterfronts, and beneath the city’s streets: The Tunnel: The Underground Homeless of New York City (Yale Press and Schirmer/Mosel, Germany); Fragile Dwelling (Aperture); Transitory Gardens, Uprooted Lives, co-authored with Diana Balmori, (Yale Press); and Glass House (Penn State Press). She received her MFA from Yale University School of Art. Morton is a professor in the School of Art at The Cooper Union and lives in New York City.

Explore

Inside the Farley

An exhibition of photographs by Margaret Morton

Horizontal light: Lewerentz, Aalto and the Nordic landscape

Thomas W. Ryan explores the seminal works of Alvar Aalto and Sigurd Lewerentz in Sweden and Finland.

The city that never was: Entropy

Robin Nagle, Bill Braham, and Iñaki Abalos engage the possibilities of waste and disorder as potential points of departure for conceptualizing new urban formats.