Interview: dlandstudio

EMERGING VOICE 2013

dlandstudio

Through dlandstudio’s master plans, community proposals, and collaborations – such as “A New Urban Ground,” designed with Architecture Research Office for the Museum of Modern Art’s Rising Currents exhibition; Gowanus Canal Sponge Park, in Brooklyn; and BQGREEN, an improvement plan that reconnects neighborhoods divided by New York’s BQE highway – the firm advocates for the integration of landscape, as ecology, infrastructure, and design, into large-scale urban networks. The practice was founded by Susannah Drake and is based in New York City. On the occasion of her lecture (video below), Susannah Drake sat down with League Executive Director Rosalie Genevro to discuss her practice.

Rosalie Genevro: This series emphasizes the voice of practitioners. How would you describe your voice?

Susannah Drake: I started dlandstudio because I felt there was a voice in the profession that wasn’t being fully represented to the extent that it could; that is, a practice that really revolved around interdisciplinary design. A lot of firms would probably prefer to work that way, but for us it is more than an aspirational framework because we are actively creating our own projects and because of the way the office is organized. Relatedly, the way we go about creating those projects is significant because of the way we identify problems within the city and its infrastructure, and then work with and alongside of the systems that can often prohibit progress to push projects forward.

RG: You have a very interesting granting and piloting process. What do you, as an emerging firm, consider to be the advantages and challenges to practice in today’s economic, professional, and intellectual climate?

SD: I think one of the big struggles, particularly in New York City and probably in other large cities as well, is that young firms that want work in the public realm are not given the opportunity because of the structure of the procurement process. It’s prohibitively expensive to pursue RFPs, and in any event, the RFPs tend to go to the established firms. There’s not really a culture of innovation for young firms in the public realm. So what we’ve done to counter that, particularly when the economy went south in 2008, was to develop this different mode of practice where we started to apply for very large foundation, state and city grants. They started off small, for example from the New York State Council for the Arts. But now, we’re actually able to raise millions of dollars for our projects and are therefore able to approach the city and say, “We have the money for these projects, let’s try them out as pilots.”

Now, I don’t know if I could have done that kind of work with another administration. We have had a generally favorable political climate.

RG: City, state, or federal?

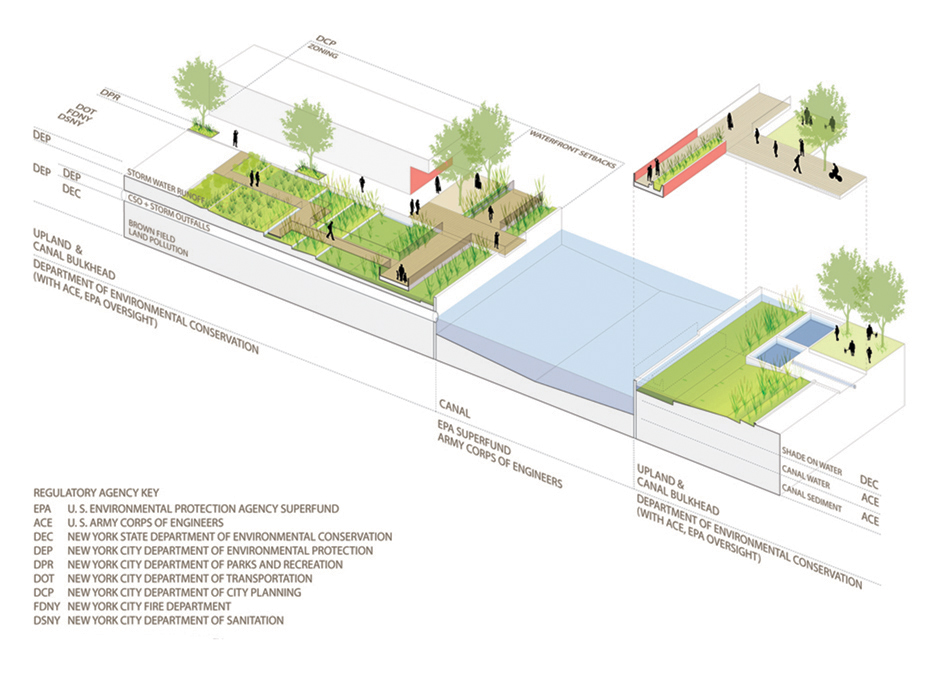

SD: We’ve worked with all different agencies. On the Gowanus Canal Sponge Park we’re coordinating with many City agencies, such as the Department of Transportation, the Department of Environmental Protection, the Department of Parks and Recreation, the Department of City Planning, the Department of Sanitation, and the Fire Department. On the state level, we worked with the Department of Environmental Conservation. And then on the federal level, with the Environmental Protection Agency (it is a Superfund site), and the US Army Corps of Engineers. Usually they all suggest that one of the others has the more complicated regulatory structure, but it’s not really any single one, it’s the entangled regulatory structures of all of them coming together. The space in between them is not only complicated to navigate, it’s also very expensive because of all of the administration and the sometimes-conflicting rules and regulations.

Gowanus Canal Sponge Park Master Plan, New York City, credit: dlandstudio

RG: So, on a project like the Sponge Park, how do you, as dlandstudio, establish your standing to be the entity that goes after implementation grants?

SD: It really started as a relationship with one organization and then expanded to become collaboration with the broader community. I think that’s really the strength of not only the Sponge Park, but also other work that we’ve been doing. Once you get a lot of different constituencies within an area to buy into your project–especially where the community might not necessarily be unified, but may have a common goal–then the elected representatives begin to recognize that you have a voice, that you’re an access point to a lot of different populations, and that it’s valuable to them to back your project.

So in the case of the Sponge Park, in listening to and working with community groups like the Gowanus Canal Conservancy, the Gowanus Canal Community Development Corporation, the Center for Urban Pedagogy, the Gowanus Canal Dredgers, and the Southwest Brooklyn Industrial Development Corporation, we were able to understand their needs, have our design respond to a lot of those needs, and gain their support. Marshaling the constituencies of these groups, we were also able to get the backing of the Brooklyn Borough President, two different City Council District Leaders, and our Congresswoman, Nydia Velázquez. All of that support also came with money: a federal appropriation grant of $300,000 from Velázquez’s office, and close to $700,000 from David Yassky and Bill de Blasio, when they were serving on the City Council.

RG: And through whom does the money actually flow?

SD: Well that’s an interesting question, because it could’ve gone through any number of City agencies. The City Council money ended up flowing through the Department of Environmental Protection. The other $300,000 from Velázquez ended up going to fund another project, but none of this money actually funded our design work.

RG: Right. I am fascinated by this approach you have of generating projects and finding ways of moving them through, but I am curious how it actually works as a business model–are you ever able to recapture the time that you spend upfront to get things going?

As access points to a lot of different populations, our projects can be valuable to elected officials.

SD: On the first one, the Sponge Park, we’ll probably ultimately break even. We’re getting better at it since we have learned how the systems work and now dlandstudio has a reputation for doing this sort of thing. I’m working with community groups to have them do more of the grant writing while I provide more of the design expertise, so it becomes more of an equal collaboration. Also, the grants we’ve been applying for have become significantly larger over time, because now we have credibility with all of these federal and state agencies. Last summer we applied for, and got, a $525,000 grant from the state to finish the Sponge Park design–roughly half of the grant is going to come directly to my firm and then half of the grant is going to the Department of Environmental Protection–and I believe it cost us about $10,000 or $15,000 to apply for the grant. But if you think of what it costs for a standard RFP process, where you’re competing with so many other firms, the cost can be many multiples of that. When you’re applying for an RFP it’s an all hands on deck situation. It’s incredibly emotionally and financially draining. Also protracted contract negotiations with the city or not for profit fiscal conduits can also eat up all of the profit.

RG: You’re trained both as an architect and a landscape architect. Talk a little bit about that and how the two disciplines have informed one another in your practice.

SD: I went to Dartmouth for my undergraduate degree and majored in art history and fine arts. After I graduated, I worked at an architecture firm in New Hampshire and a landscape firm in San Francisco, and ultimately I ended up deciding to pursue both academically. I like working with the landscape, but I also really like thinking about an architectural level of detailing. The issues between them are really about scale and tolerance of media. You can’t just detail landscapes the same way you would detail architecture. The tolerances are very different; the materials are obviously very different. When you design a landscape, it is only just the beginning; it’s never really “completed,” whereas in architecture, that moment of completion is really palpable and satisfying because you have something that you’ve built. You can photograph it; you can feel good being in it. With a landscape it’s really out of your control. I like switching back and forth between those two modes, and I think now in my practice what I do is think about prototypes of almost an architectural level of detailing that can be applied on a massive level to infrastructure problems that have a more global impact.

RG: How does that play out in your office now? Who do you have working at dlandstudio, and how do you approach a design problem?

SD: Staff-wise, I have architects and landscape architects, as well as urban designers, and a graphic designer. We had an astronomer once. The office is a studio and there’s a lot of intermixing of people and ideas. It’s not very efficient financially, but great in terms of the development of very rich projects. Everyone brings their expertise to bear, whether it’s about horticulture or drainage or sculpture or policy. We have an intern who is a civil engineer, or, rather, a civil engineer turned landscape architect. When I get the sense that I need to build a particular area, I’ll bring in someone that has that expertise. We try to hire people that have weird combinations of experiences, like a horticulturalist who did architecture undergrad, and who’s also structural engineer. All of those diverse skills playing off of one another creates a pretty rich outcome. One of the best people I had, who unfortunately left to raise a child, was trained as a sculptor after doing an architecture degree. She really understood the materials.

Glimpses of New York and Amsterdam 2040: Hybrid Urban Base (HUB), Hunter’s Point, Queens, credit: dlandstudio

RG: Along those lines, I wonder what you would say about being a woman in practice? It’s a big topic these days; it has resurfaced after not being talked about for a long time.

SD: It’s a very rich subject. From a management perspective, it is something I think about quite a lot. I was interviewing for a job this week, and the person interviewing me asked me about the qualifications of our firm, more specifically, why we didn’t have an environmental consultant on our team. I said “it’s because we’re landscape architects, and this is what we do,” but then went on to list our qualifications. Afterwards I thought, “I may have seemed defensive, strident or too aggressive,” things that I think a man in my position would never ever think about. He would just say, “I’m the landscape architect, and this is what we do.”

RG: Do you feel any special obligation to your employees?

SD: Being a supportive role model and advocate for women in design is a strong motivating force behind both my teaching and my practice. I recognize that societal pressures hold some women back from taking on a greater leadership role, so I try to be very open about my own experiences. With few female mentors, disproportionate responsibilities related to child rearing, low salaries in the design professions, and a need to operate within existing power structures, women face tremendous obstacles on a path to leadership. This is often characterized as a problem of the profession that women must bear– but the responsibility for parenting falls on both men and women.

Public programs intended to help surmount some of the obstacles for women in practice often only serve to reinforce the problem.

What’s more, public programs intended to help surmount some of these obstacles often only serve to reinforce the problem. With state and city contracts, for instance, Women Business Enterprise (WBE) firms only get credit toward the recommended inclusion guidelines if they are in a subservient relationship to the primary firm. There are significant administrative costs to becoming and maintaining WBE status that can only be recouped if you don’t lead projects. What was intended to be a well-meaning law is a perfect example of a glass ceiling in the profession. Women are invited to play the game but can’t be the captain. The Pritzker and AIA Gold Medal awardee histories drive home this point.

RG: What are you working on now that you’re most excited about?

SD: We just started work on the first wetland mitigation bank in New York State. Through a project initiated by New York City Economic Development Corporation, as a sub contractor to a larger engineering firm, dlandstudio is developing a healthy wetland in Staten Island. The idea is that developers, who are building in other parts of the city, can buy into this bank rather than doing their environmental mitigation on site.

RG: So it is like an 80/20 Housing Program for wetlands?

SD: Yes, in a way but not all on one site. It is a program that has been done in a lot of other states, but not in New York, because there has been some fear that it would be abused. But I believe it can be hugely beneficial, especially if you are strategic about the location. There are places where development of a wetland edge is not viable or practical. In these cases it makes sense to offset damage done I one area by pouring money into the restoration and maintenance of a healthy landscape. Additionally, with landscapes, bigger areas or connected greenways are more environmentally productive than separated patches. This is a theory that landscape ecologist Richard Foreman wrote about most eloquently. His theory about patches and corridors demonstrated that patches of landscape, like backyards that are unconnected, for instance, are not as healthy as places where you have long, linear corridors. Habitats are built on the scale of a landscape; certain birds will only nest in an area that’s big enough. Providing conduits for those animals and ecological flows around the development zones and around our infrastructure is important for a healthy ecology.

HOLD SYSTEM: Flushing Bay, Queens, NY, credit: dlandstudio

We have two other projects under construction that we refer to as Highway Outfall Landscape Detention Systems, or HOLD Systems. They are essentially smaller, modular green infrastructure systems that are deployed around the drainage outfalls of raised highways. They capture that water and run it into a planted swale that will hold it where natural evapotranspiration can occur. Whatever water is able to infiltrate out of the swale will be much cleaner. We’re working with Paul Mankiewicz on some of these; he is such a wonderful, brilliant man (ED–see a lecture Mankiewicz gave for the League in 2008, and his interview on Urban Omnibus from 2013). In the Bronx, we’re actually creating a floating wetland using his Gaia Soil, because City regulations mandate that you can’t have standing water for more than about 24 hours. In our project the plants will actually float up and down on this soil membrane. It is a pilot project, but we’re hoping to prove and refine this idea so that it can be deployed in many other locations throughout the city.

•••

Susannah Drake, dlandstudio, Emerging Voices 2013, complete lecture video | Recorded March 14, 2013 | Running time: 38:13

•••

Susannah Drake received M.Arch and M.L.A. degrees from Harvard University and has taught at Syracuse University, The Cooper Union, Harvard University, and the City College of New York. The recipient of numerous AIA and ASLA awards she is a former President and a current Trustee of the New York ASLA. See more of her firm’s work at dlandstudio.com.