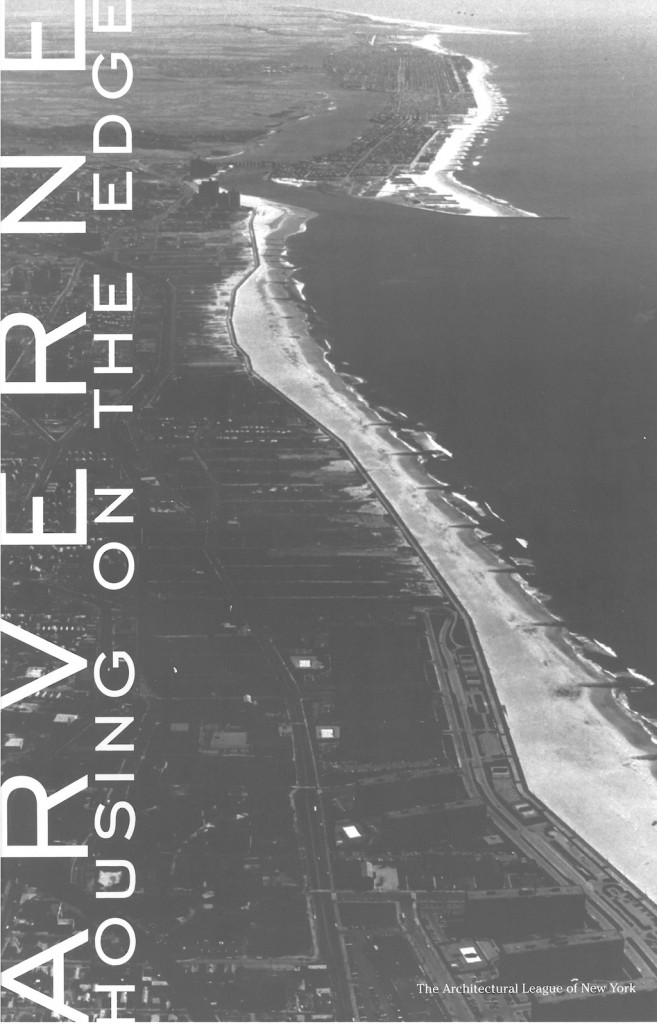

Arverne: Housing on the Edge

A 2001 exhibition considering four proposals for the Arverne Urban Renewal Area on the Rockaway peninsula in Queens.

December 7, 2001—January 16, 2002

Introduction to the exhibition publication, 2001

In December 2000, the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) issued a Request for Proposals for a large section of the Arverne Urban Renewal Area on the Rockaway peninsula in Queens. The RFP invited developers to submit proposals for the development of market-rate housing and community and commercial facilities on the largest developable tract of vacant land in New York City. The site has a magnificent natural situation, towards the western end of the barrier beach that runs the length of the southern edge of Long Island—the same beach that includes such fashionable resorts as Fire Island and Southampton. Arverne itself was a fashionable resort in its heyday, from late in the nineteenth century well into the twentieth. But the vacant land in Arverne that is the subject of this exhibition has lain fallow since it was created through clearance in the late 1960s. Arverne was designated an urban renewal area in 1965, by which time its barely winterized beach bungalows, inhabited largely by poor families and individuals displaced from urban renewal sites elsewhere in the city, or more recently from further west on the peninsula, had become a slum with conditions “as bad as in the worst ghettos,” according to the Department of City Planning’s 1969 Plan for New York City. In the more than thirty years since 1969, Arverne has proved both seductive and resistant; the large-scale housing and “attractive, year-round regional and local recreation” uses planned when the site was cleared were never built. Subsequent attempts at development, including a 1989 City-designated effort by the developer Forest City Ratner that advanced to very detailed planning and architectural design, have for various reasons never come to fruition.

At the time HPD issued its Request for Proposals, the Architectural League asked four teams of architects—each team with an academic or research affiliation—to carry out a parallel investigation of possibilities for the site. The League had begun discussions with HPD earlier in 2000 about possible collaborations that might raise the quality of design in HPD-subsidized or facilitated developments. We eventually agreed to work together on Arverne, with the thought that the independent design investigation would precede the issuance of an RFP. Other considerations speeded up the RFP process, and HPD and the League agreed that the Arverne investigation would function, in Michael Sorkin’s suggestive analogy, as a kind of amicus brief for the Department-ideas that could inform the Department’s decision-making on this and future projects by offering alternative points of view about the problems and possibilities of the site and what sorts of urban, landscape and building design might be desirable for its development. The future development of Arverne is a particularly fertile subject, because it combines the question of how to carry out large-scale planning with the possibility of analyzing and proposing alternatives to what has become the overwhelmingly dominant mode of housing development in New York outside of Manhattan: the one or two-family rowhouse. Arverne also offers significant environmental challenges, because of the relative fragility of its dune landscape and its vulnerability to storms. The municipal infrastructure of the site—streets and sewers—has deteriorated over the years of vacancy, and needs to be rebuilt or reconceptualized if new development is to take place.

The teams whose work is on view in this exhibition are connected with four institutions: CASE, a new Dutch research foundation; the City College school of architecture; the Columbia University school of architecture; and the Yale University school of architecture. The four teams took very different approaches, each of which is very different from standard development practice in New York City in 2001. The emphases of the various projects—an interest in reintroducing multiple dwellings rather than relying on the single and two-family house, in exploring untypical ways of exploiting manufactured building components to reduce construction cost, in paying particular attention to site and landscape design out of respect for the ecology of the site, in considering a much larger context than either housing or this specific site alone—all suggest important avenues for further exploration in housing development in the city.

CASE

John Bosch, Bruce Fisher, Reinier de Graaf, and Beth Margulis; with Cecile Calis, Bart-Jan Hooft, Unal Karamuk, Juerg Keller, Wendy Saunders, Peer Frantzen, Blake Goble, Oliver Ospreik, Christine Rogers, and Peter Zuspar, Jens Keller, Hajime Narukawa

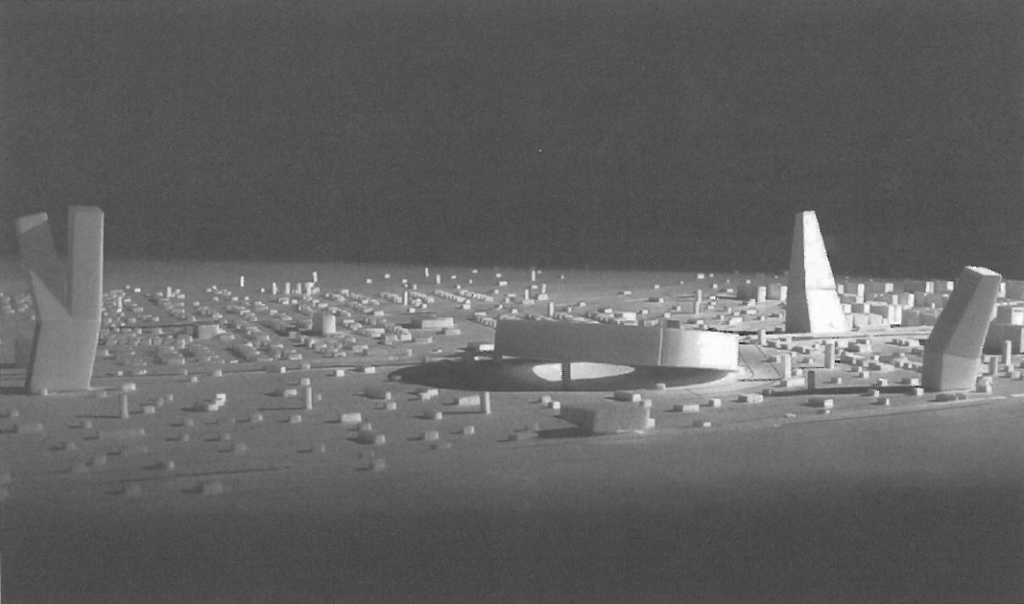

Four architects—John Bosch, Bruce Fisher, Reinier de Graaf, and Beth Margulis—founded CASE in 2000 specifically to explore questions of large-scale development and to reassert a role for architects in the planning and design of housing. CASE’s proposal for Arverne looks at the potential for the area’s evolution over a few decades, with Kennedy airport as the economic driving force. They analyze land use patterns in a large area surrounding Jamaica Bay, as well as transportation networks and economic data, and propose to acknowledge the virtual return to nature of much of the Arverne site itself by suggesting a combination of extremely low- and extremely high-density development. The development would be staged over many years, and would over time create both a new economic base and an entirely new image for Arverne and other areas of the Rockaway peninsula.

City College

Michael Sorkin Studio: Michael Sorkin and Andrei Vovk; with Jacob Kain, Jair Laiter, Victoria Marshall, Katherine Martin, Wang Waye

SHoP: Chris Sharples, Gregg Pasquarelli, Richard Garber

SYSTEMarchitects: Jeremy Edmiston, Douglas Gauthier, Henry Grosman, Joe Jelinek, Salomon Frausto

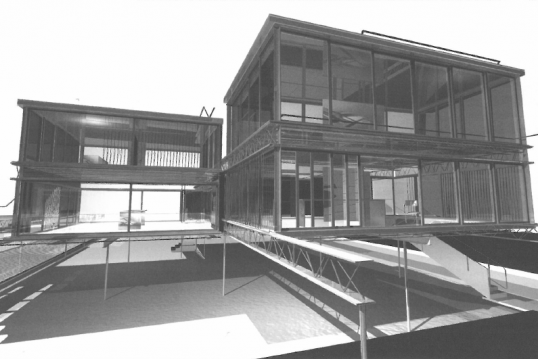

The City College team—the Michael Sorkin Studio with SHoP and SYSTEMarchitects—exuberantly embraces the beach. The Sorkin Studio’s master plan creates public access to the beach from the elevated train through a wide swath of planted area that sweeps down from the Beach 67th Street station. The edges of the built area on either side of this green sweep contain commercial and public uses, and the proposal overall suggests considerable spatial variety in the spectrum of outdoor spaces and building forms, including a stretch of Copacabana to the east of the main site. The SHoP/SYSTEM proposal for one sector of the plan creates a kit of transforming, multiple purpose building components by way of suggesting that the real American vernacular was distinguished not by its image but by its propensity for tectonic invention and play.

Michael Bell Architecture: Michael Bell, Anthony Burke, Alex Phieffer, Todd Vanvarick, Josh Uhl, John Mueller, Kory Bieg

Marble/Fairbanks Architects: Scott Marble, Karen Fairbanks, Jake Nishimura, Lars Fischer, Todd Rouhe, Benjamin Hummitzsch, Maya Galbis, Laia Massague

Mark Rakatansky Studio

Michael Bell Architecture, Marble/Fairbanks Architects, and Mark Rakatansky Studio, the Columbia team, all focus on the reconsideration of building type. They have divided the site into three sectors and focused very intensively on designing buildings that make a transition from the few remaining bungalows and the new one and two-family construction on the east side of the site, to the high-rise slabs on the west. Within each sector of the site they also propose a mix of dwelling types and sizes, including live/work units.

Diana Balmori, Deborah Berke, Peggy Deamer, Keller Easterling; with Ben Bischoff, Mike Tower, Theodore Whitten, Matt Kelley, Takanori Fukuoka, Javier Gonzalez Campaña, Nathan Howe, Karen Lau, Cecelia B. Martinic, Jeffrey M. Tucker

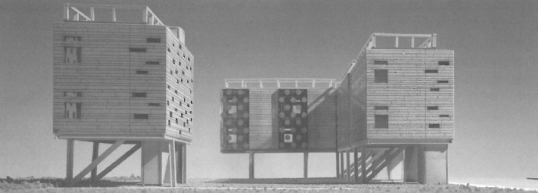

The Yale team, led by Diana Balmori, Deborah Berke, Peggy Deamer, and Keller Easterling, reinvent both the housing structure and the landscape from economic and environmental perspectives. The design and construction approach for the housing blocks has been chosen to minimize cost and maximize speed while creating an extremely energy-efficient building, which could then be deployed at a variety of densities. The landscape strategy minimizes or does away with the need to rebuild a “hard” drainage and sewer system, by proposing a natural infrastructure that handles drainage, and the use of a “living machine” to treat effluents created on the site.

It is very difficult to change a system as complex as housing production, influenced as it is by financial structures, perceptions of the market, construction practices, government regulations, and cultural values. Every so often, a shock to the system, in the form of ideas that are radically different than accepted practice, can provide a useful jolt that opens up awareness of the enormous number of other ways of doing things. We hope that these projects, with their great wealth of analysis and invention, can serve that purpose.

—Exhibition publication text by Rosalie Genevro, Executive Director, Architectural League, 2001

Project Director

Rosalie Genevro

Exhibition Design

Shauna Mosseri

Exhibition Graphics

Tricia Solsaa

Publication Graphics

Rion Byrd

Exhibition Production

Brendan Atkinson, George Evageliou, Rose Evans, Alex Forman, Takeshi Nakanami, Aric Obrosey, Jason Smith

Arverne: Housing on the Edge was organized by The Architectural League and carried out in cooperation with the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development. The League gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Jerilyn Perine, James Lima, Susan Ponce de Leon, Christopher Cirillo, John Waters, Brett Libresco, Ben Dookchitra, and Barbara Skarbinski of HPD.

Explore

City as living room: Single and shared housing in the Bronx

For the Making Room design study, Team 8 designed housing for underused sites along the Grand Concourse.

Density diversified: Three housing types for Ravenswood, Queens

For the Making Room design study, Gans Studio designed housing for the individual resident and the larger urban context simultaneously.

GoHome: Shared housing tried and tested

A design study assesses the distribution of micro-units in residential high-rises to provide more rentable space.