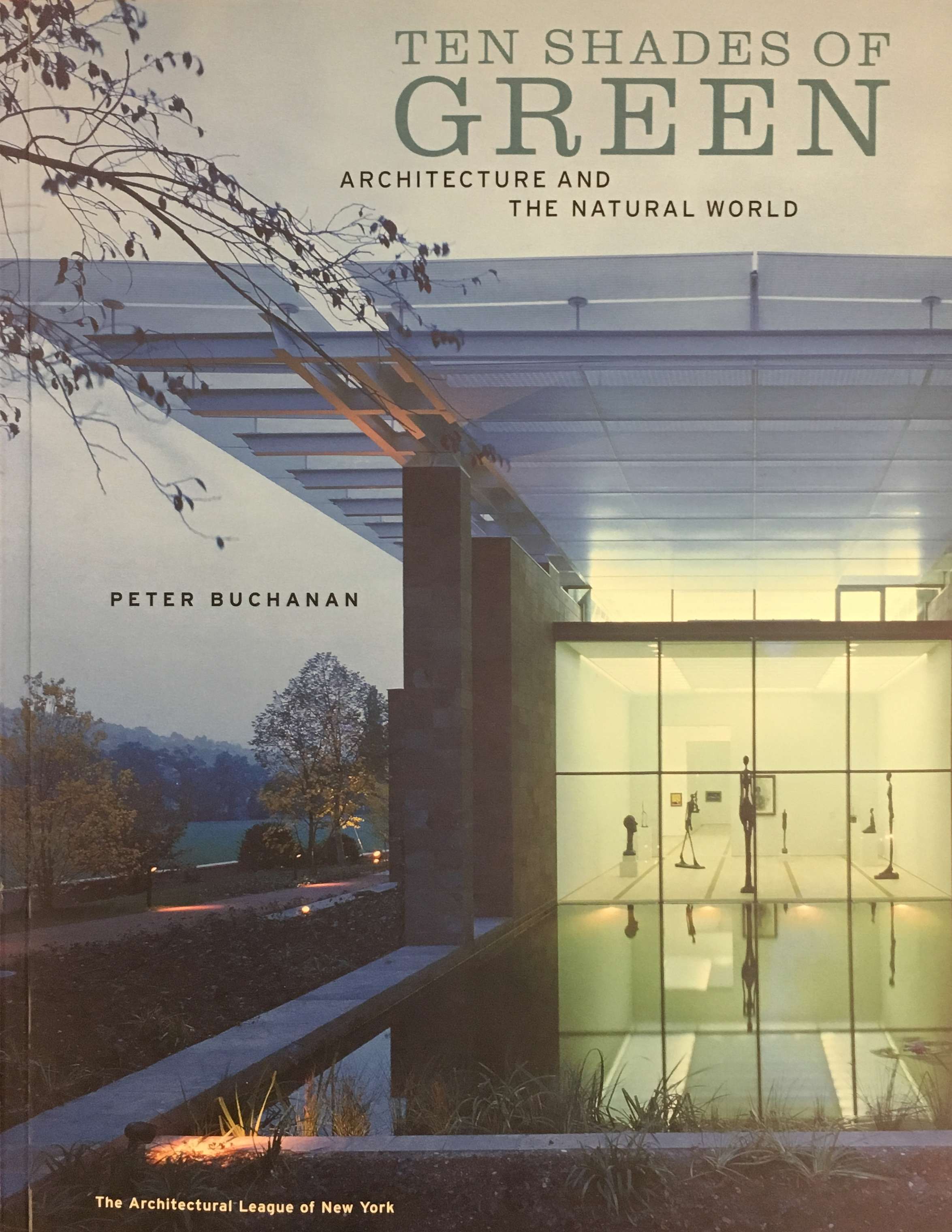

This book documents the exhibition Ten Shades of Green, organized by The Architectural League, with Peter Buchanan as curator, and launched in New York in the spring of 2000.

The League’s goal with Ten Shades was straightforward: to show examples of work that combined environmental responsibility with formal ambition. Peter Buchanan accomplished that goal, beautifully, in the projects he chose and described, which range widely both in formal composition and in the ways in which they engage environmental issues. He also created something larger: a context for understanding those projects, and for evaluating all works of architecture and land planning, that embraces a range of concerns from technical efficiency to communal well-being to emotional resonance. Ten Shades of Green struck a chord, and the exhibition traveled to galleries and museums all over the United States from 2000 through the end of 2004, propelled by word of mouth of architects who had seen it and wanted to bring it to their own cities and institutions as a way to educate and move their communities forward.

At the time the exhibition opened in New York, and that Peter Buchanan’s essay in this book was written, the current cycle of environmentalism in American architecture was just coming into focus. The United States Green Building Council, a consortium of building industry companies, firms, and individuals, had been formed in 1993 and launched the first public version of its LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) standards in 2000. Four Times Square, a skyscraper by Fox and Fowle Architects and one of the most publicized early works of a new generation of green buildings, opened in New York in 1999. Members of the American Institute of Architects formed the first chapter of the Committee on the Environment in the mid 90s.

Since then there has been a great deal of activity and progress in the relationship of American architecture to environmental issues. A large number of architects have begun to embrace the basics of environmentally responsi· ble design, and there is much talk among architects and their clients about LEED certification, about gaining the technical proficiency to achieve LEED “silver” or “gold” or “platinum” buildings. No large firm, or small firm for that matter, can afford not to market their “green” capabilities as they seek commissions. Public and institutional clients from the federal General Services Administration to cities and universities around the country have made creation of “green guidelines” a priority in their building and infra· structure development programs. The spring of 2005 brought the news that the mayors of 132 American cities have pledged to meet the Kyoto goals of reducing green· house gas emissions by 7% from 1990 levels by 2012. A number of the design leaders of the profession have taken on sustainable design as a conscious determinant of form in their work, in buildings such as recent Pritzker Prize winner Thom Mayne’s CalTrans headquarters in Los Angeles and San Francisco Federal Building. A few influential devel· opers have made environmental responsibility a priority in their projects, and have sought out architects who can meet their ambitions.