UUfie’s material world

Unconventional material choices add a dimension of novelty and surprise to the work of Toronto-based UUfie.

An interview with Irene Gardpoit and Eiri Ota of UUfie, one of the 2019 Emerging Voices.

Toronto design practice UUfie creates playful, approachable projects that range in scale from furniture to landscapes. Partners Irene Gardpoit and Eiri Ota often use familiar materials in unconventional ways, adding a dimension of novelty and surprise to their work.

The Architectural League’s Sarah Wesseler spoke to Gardpoit and Ota about their design process.

*

How do you think about materiality when you set out on a project? Is exploring different materials a priority?

Eiri: We don’t care about material independently, but it’s a really important component for us. We care about materials and lighting quite a lot. If you don’t have light, you don’t see the space. And material is what surrounds the space.

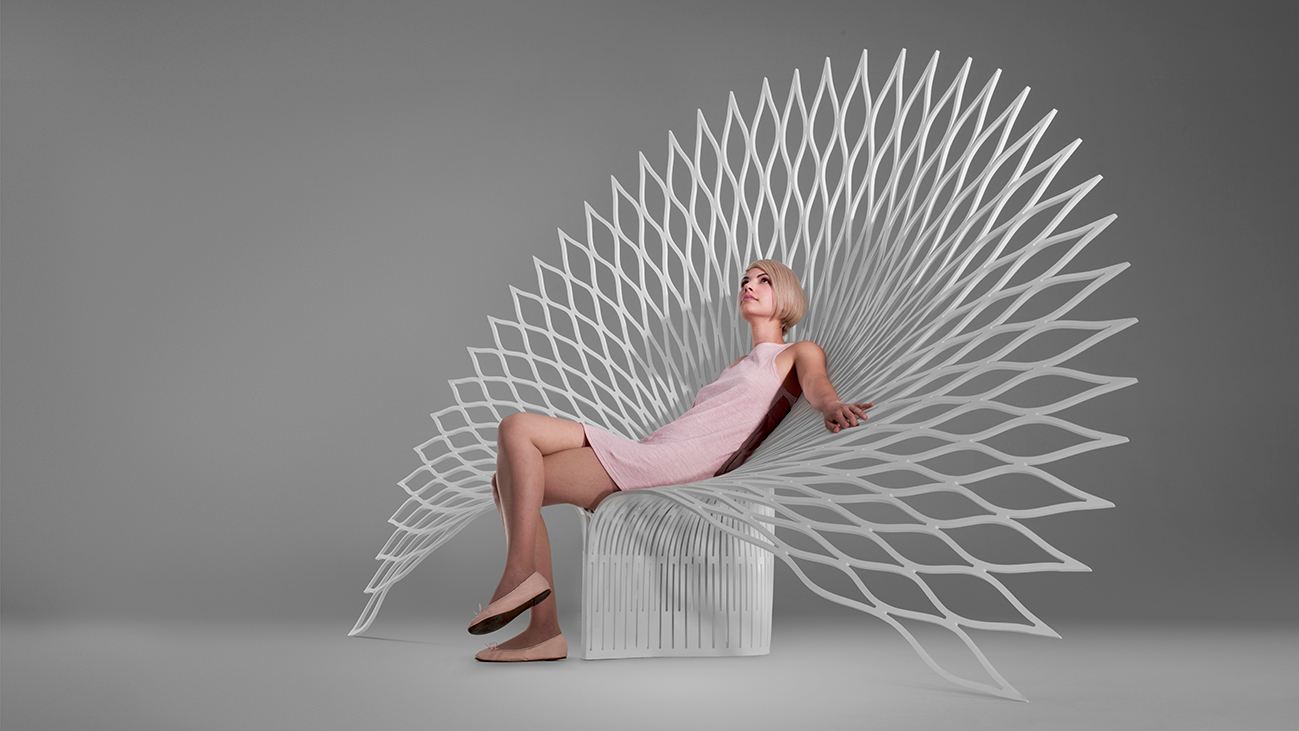

Your Peacock project is made from Corian. How did you decide on that material?

Irene: The project actually started from the material itself. We were commissioned to do a space in an interior design show in Toronto. The show’s sponsor was DuPont, and DuPont asked if we could design something to showcase Corian.

Eiri: We researched the material and found that we could use a technique called thermoforming. Once you heat Corian you can form it and freeze it. So we were thinking how to bring this possibility of the material into the form.

We came up with the idea of capturing a moment of beauty in nature: the moment of a flower blossoming, or the peacock’s tail fanning out. So we translated the material’s character into the design.

How did you decide what materials to use for the Printemps Haussmann department store?

Eiri: I probably need to start from the context of the building. It’s an old Art Nouveau building, a historic building in Paris. But since it was completed, there have been several fires and reconstructions. A lot of its historic features were destroyed or removed. The existing building has an Art Nouveau façade, but the inside was destroyed a long time ago. There was no historic character anymore; it was filled with anonymous floor plates. Our goal was to bring the character and the history back. That was the starting point for our design.

Printemps has two buildings, side by side. Our building had only the historic façade, but the building beside it has a stained glass dome that they rebuilt after a fire. Our design took the idea of the stained glass dome that was destroyed and used it for today’s contemporary design.

The space was very constrained because of structural limitations. Our idea was to insert a three-dimensional curved surface from the second floor all the way to the ninth floor, and then install the escalator just beside it. So people would be going up and down, and their distance from the curved wall would be constantly changing, and the viewing angle would also be constantly changing.

We were wondering, is there a way that people can interact with color? Dichroic glass was a very good solution here, because it changes color as the viewing distance or angle changes. It also has a very highly reflective character; it reflects the back side of the aluminum panel and creates internal reflections. So it has a double change in gradation, one according to the viewing angle, and one by the internal reflection. As a result, one hole in the panel creates three different types of color in the same moment.

Tell me about your retail stores for Ports 1961.

Irene: Ports 1961 is a very simple design, actually. The standard glass block is square, but we devised a large L-shape glass block by mitering the corner of two standard glass blocks and heat-welding them together. So the Ports 1961 stores in Shanghai and Hong Kong use only two materials: flat glass block and corner glass block. Adding the small touch to the existing material allowed us to take a plain, flat surface and give it more three-dimensional movement.

How did you decide to use glass block?

Eiri: Since it’s a fashion brand and stores were opening in several locations, we were thinking, how do we maintain a design language in various sites? Then we started to think about icebergs. An iceberg is always migrating from one place to another place, but its shape is formed by its environment. So if we designed each façade and building like how the iceberg migrates from the city to city, probably we could fit many site contexts with one design.

Then we started to think, what’s the simplest module we could use to create the form? Probably a square cube—which we can create from glass block.

Another benefit of glass block is that we can make a daytime appearance that’s very monolithic, like a stone, and in nighttime it can appear like a lantern. So it’s subtle, but also has an impactful appearance in the various cities.

Did you have to do a lot of testing to determine how to modify the glass block?

Eiri: Yes, we did several tests. The first was, is it possible to miter and heat weld or not? So we worked with the glass block manufacturer directly. Then the second was, how would we actually install it, including the structural system in the back? How would the shadow appear, how should the lighting be set into the place? We tested everything in mockups.

What general process do you follow to work through your design ideas on a project?

Eiri: The first stage is to try to understand what, actually, we should focus on. That’s a key point for us. For example, in Peacock, the material has many, many different properties, but which has the most potential? Which voice we should pull out?

And for Printemps, the project started from a competition. I don’t know what other people proposed—our proposal was, okay, let’s focus on the history of the building. Finding the focal point is important.

After that, we do a lot of studies with physical models. That’s probably very Japanese. [Gardpoit and Ota met while working in Tokyo.] We also do a lot of hand drawing. In the end it’s always a majority of CAD drawings, but before that, especially in the detail level, there is a lot of hand drawing.

Have you ever wanted to use a particular material for a project but found that it wouldn’t work?

Eiri: Every material hits some problems, for sure. But it’s when that happens that it starts to look like there is a chance there, some design hint. It helps, actually.

So we never try to control the material to be what we imagine in the beginning. It’s a process of understanding.

Does your process change when you work on different project types, like when you go from designing a piece of furniture to creating a building?

Irene: Surprisingly, it’s the same for us.

Even on bigger projects or landscapes, the way we think about design is pretty much similar. Of course, the way we realize the design is different. But the design process is quite similar.

Interview condensed and edited.

Explore

Interview: Williamson Chong Architects

Donald Chong, Betsy Williamson, and Shane Williamson marry traditional materials and construction methods with emerging technologies.

Material tour de force: The work of Eladio Dieste

Julian Palacio visits Uruguay to examine the material and structural innovation of the work of engineer Eladio Dieste.

Omar Gandhi lecture

Canadian architect Omar Gandhi, winner of a 2016 Emerging Voices award, discusses his work.